By Kelsey Ronan

Detroit is a city of contradictions. It’s a city stricken by poverty and population loss, of blighted lots receding into urban prairie, a damning testimony against capitalism. But it’s also a city of determination and invention, reclaiming itself through grassroots initiatives and creative renewal.

The challenge of writing about Detroit is doing justice to all those contradictions—to capture how catastrophe and renewal coexist in the city’s sprawling boundaries. How do you describe a devastated industry without exploiting its broken windows and graffitied factory walls for ruin porn? How do you capture the optimism and courage of the city’s entrepreneurs without rendering them naïve cheerleaders?

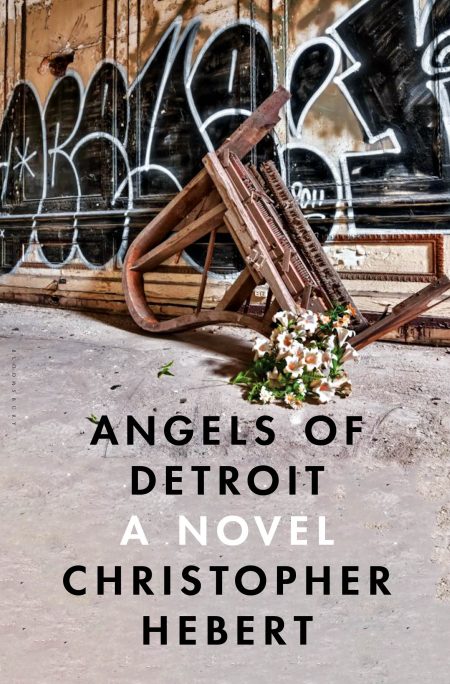

In his new novel, Angels of Detroit (Bloomsbury), Christopher Hebert takes on the many lives and landscapes that make Detroit so complex. The novel’s expansive cast includes millennial artists and activists, the last of the city’s corporate millions, children living in near-empty neighborhoods, and urban farmers. Written with vivid compassion, Hebert’s characters represent Detroit’s many generations, races, and socioeconomic divisions. As their lives intersect, a multifaceted Detroit takes shape: a city to grieve, and a city just getting started.

Angels of Detroit is, as Hebert explains in the interview that follows, “neither an indictment nor a sugar-coated celebration of Detroit.”

BELT: You mentioned that St. Louis was an inspiration for the novel. How did St. Louis (and perhaps your experience of the Rust Belt more generally) inform this novel?

Christopher Hebert: There were three places along the Rust Belt that really influenced this book and helped shape me as a writer. The book is set in Detroit, but the very first seeds for the book were planted in St. Louis, and my Rust Belt preoccupations began much earlier in Syracuse.

I grew up in Syracuse, part of the Rochester-Buffalo Central New York Rust-Belt Corridor. Relative to places like St. Louis and Detroit, Syracuse is fairly small scale, but like them it’s a shrinking city, once a manufacturing hub, now losing population, a disappearing economy, plenty of industrial scars and neglected spaces. When I was a kid, downtown Syracuse was a ghost town. As a kid in cities like these, you spend a lot of time confronting the remains of a not-quite-vanished past. You see buildings and they’re empty. Or lots that are vacant. What remains is faded. And you know something happened—people once lived there or worked here, and now they’re gone. But where did they go? What happened?

As I got older, I read and researched and found the answers—intellectually, socio-historically. What happened isn’t a mystery: segregation, economics, urban planning. It’s all quite knowable. But for me at least, the questions remain at some basic level emotional—or spiritual maybe—that sense of loss that feels tragic because a lot of it was so avoidable.

I inadvertently spent a lot of time traveling the Rust Belt, going off to college in Ohio, and then after I graduated I moved to St. Louis. There I became much more attuned to the racial component, as well as to the urban-suburban tensions. I lived with a friend in Soulard. When we moved there in 1998 there were bits of gentrification going on, but where we lived was pretty run down. My friend was an artist, and we found an old industrial building where there were artists’ studios, and we talked the landlord into letting us live there. The apartment in the book where McGee and Myles live is modeled after it, though ours was even more Spartan—all we had was a shower stall and a utility sink.

I worked out in the suburbs, at Library Ltd., a bookstore in Clayton that’s since gone out of business. The contrasts were obviously stark between the city and the suburbs—economically, racially. But maybe the most striking thing of all to me were the gated communities. I’d never seen so many, like the entire inner ring was a giant locked door. I never saw anything like it, before or since—so concerted an effort at what felt like a walling off of a city.

One day I was making the drive from Soulard to Clayton and I was listening to a local public radio station, and there were experts on the air talking about the city’s problems—a pretty familiar topic. But on this particular day they were discussing an idea I’d never heard before: the logistics of converting St. Louis to farmland. Basically accepting there was no point in continuing to try to keep St. Louis alive as a city. The argument was that we should just face the fact that it would never again be what it once was. I thought at first it was a joke. But within a few minutes I realized they were dead serious. That was the moment, there in my car, that this book was born. It really was that immediate, the realization of what I wanted to write about, although it would be many years before I actually succeeded in doing it.

After St. Louis I moved to Ann Arbor, and I started spending a lot of time in Detroit. Eventually I became an editor, working for a publishing house, focusing a lot on books about Detroit. In Detroit I heard the farm debate all over again, and I reproduced it in one of the first chapters in the book, as something animating several of the characters.

Early on in my writing, the setting of the book was a bit of a hybrid between Syracuse and St. Louis and Detroit, bits and pieces of each. Gradually—because it became front-and-center in my mind—Detroit took over, but the influence of St. Louis and Syracuse is still there.

BELT: Some of my favorite passages in Angels of Detroit are from Ruth Freeman’s perspective—her memories of Detroit in the 1950s and 60s leading up to the 1967 riot. What was your research process like? How did you access that nostalgia?

Hebert: Those were some of my favorite passages to write. I wrote that chapter about Detroit in the 50s and 60s fairly late in the process. The book grew very organically, more by instinct than by plan. As I went I kept finding new pieces of the story I wanted to explore. One thing I always knew was that this was never going to be a simple book with a clear agenda, neither an indictment nor a sugar-coated celebration of Detroit. I really wanted to explore the story and these characters from all sides. Eventually I reached a point where I realized I needed a moment where this kind of nostalgia could be acknowledged, a counterweight to the preponderance of grim material within fairly easy reach.

This was definitely the most research-intensive material to write. I really had to go back and reconstruct a 1950s Detroit as it might look to a fairly privileged teenage girl. I read everything I could find—books, newspapers, web forums where people who’d grown up then reminisced. It helped that by now I’d lived long enough with Ruth Freeman that I felt like I knew who she was as an adult, but it took me a while to find my entry into her past. I actually use this nostalgic chapter as an example when I talk with my students about how exploratory the writing process can be. You fumble your way through it blindly until something clicks. In this particular case, that meant writing a lot of pages until I happened to arrive at the line “Ruth Freeman had never cared for cars.” Then I threw away all of those pages I’d written except for that one line, and that line became my starting point. It seems obvious now that cars would be an easy angle for approaching Detroit in its heyday. But more important, the line captured Ruth’s brand of contrariness—the one person in Detroit indifferent to cars, except as a means of getting her where she wanted to go. Then I focused my research on figuring out where she would want to be going. Belle Isle looms fairly large because I love Belle Isle, and it’s one of those places for me that feels especially haunted. I’d known it myself only in the years leading up to it being shuttered, and I was interested in exploring its past.

BELT: Angels of Detroit has an expansive cast of characters. Who did the writing begin with?

Hebert: This was one of the ways in which the book evolved organically, by instinct. I started with Dobbs—the old “a stranger comes to town” plot line (although I wasn’t thinking of it in those terms at the time). When I started out, I needed him as a stand-in for myself, someone wandering the streets trying to make sense of things. Early on he was my vehicle for discovering the other characters. As I discovered them, I found myself wanting to follow them too, wondering what each of their stories was. Gradually I saw that I was writing a book that really wanted to be a blend of voices and perspectives, that I was attempting to capture the sense of a fragmented community. That made it fun to write, getting to move around and imagine so many different lives. But it also created some serious problems. Once I established that each chapter would be distinct, originating in one particular perspective and containing its own fairly complete narrative arc, I had to find ways to link things from chapter to chapter and make the plot lines advance. Which is a big part of the reason it took me almost sixteen years to write this.

BELT: Angels of Detroit takes its title from a Philip Levine poem. Were there any writers (Detroiters or otherwise) who influenced how you wrote about Detroit?

Hebert: Yes, absolutely. Levine is the great chronicler of Detroit, especially the blue-collar world. In terms of Detroit, there’s also Jeffrey Eugenides and Joyce Carol Oates, who—I don’t know, maybe it’s just a coincidence—was originally from Buffalo (Oates, that is), so I always saw an interesting connection there for both of us between Central New York and Detroit. As an editor I published Susan Messer’s Grand River and Joy, a wonderful novel about a Jewish family in Detroit and racial tensions leading up to the riots. Harriet Arnow’s The Dollmaker—though I read it too late for it to have been influential—is a dense and fascinating social-realist document of the early 20th century migration of southerners to Detroit. It’s especially interesting to me now that I’ve made the reverse migration myself from Michigan to Tennessee, following (accidentally again) the flow of a lot of former Rust-Belt industries (including auto manufacturing) into Southern Right to Work states. Among writers associated with Michigan, I love Bonnie Jo Campbell and Charles Baxter, who was a mentor of mine.

But the book I probably had on my mind the most early on was Jonathan Franzen’s The Twenty-Seventh City, which brings me back again to my book’s St. Louis roots. The Twenty-Seventh City was Franzen’s debut novel, a postmodern satire quite different from his more recent—more traditional—family sagas. Stylistically, the book was a bit over-the-top for me, but it was an important touchstone in that it was an ambitious attempt to engage with a lot of the Rust-Belt issues that have been so important to me.

BELT: There have been several Detroit novels in the last few years, and I’m fascinated with how they each confront the task of describing Detroit’s ruins. Though your characters interact with those ruins, some looking to destroy while others work to salvage, the prose around those ruins is sometimes spare, or emphasizes scale rather than gritty detail. As Dobb explores the city, he uses phrases like “mile after mile of emptiness,” and thinks very succinctly of one empty factory, “The place was huge.” What was your process in making Detroit’s landscape take shape in Angels? Did you have any anxieties about accusations of “ruin porn?”

Hebert: I worried (and continue to worry) a lot about that. It’s hard to find the right balance. On the one hand, you don’t want to be exploitative, and it’s all too easy to find startling images you can deploy for dramatic effect. At the same time, though, you can’t pretend this stuff doesn’t exist. I’m all for saying nice things about Detroit, but I don’t think it does any good to pretend the not-so-nice things aren’t there, too. My aim was to acknowledge the grit and graffiti, but in a way that makes readers want to do more than just shake their heads and say what a shame. I wanted to go deeper and explore the lives—show that they continue to be lived and that hope continues to be hoped. The ruins are there, but they’re not the end of the story.

__

Kelsey Ronan grew up in Flint, Michigan. Her journalism and fiction have appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, Indiana Review, Sycamore Review, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and elsewhere. She lives in St. Louis, where she is the fiction editor of River Styx and coordinates a creative writing outreach program.

Read more about Detroit, and support independent Rust Belt writing