By Kevin Tidmarsh

Buford Franklin Gordon’s name is unlikely to ring any bells among most residents of South Bend, Indiana. Part of this is understandable — Gordon only lived in South Bend for a period of five years, and he led an ordinary life by some measures. But Gordon’s writings about South Bend, in which he left behind one of the few records of the black community at the time, deserve to be remembered, studied, and preserved for the contributions they make to the history of race relations in South Bend and the rest of the industrial Midwest.

Gordon fought against racism his entire life. He was born in 1893 in Pulaski, Tennessee, a small town best known as the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, to an illiterate mother and a father who was born into slavery. He went on to achieve an extraordinary degree of success — he published several books, served as a bishop of the A.M.E. Zion church, and served on the executive board of the NAACP — but it was only against almost insurmountable odds, and racism that followed him from South to North.

Rev. Gordon

Having graduated from Fisk University in Nashville as an undergraduate chemistry major, Gordon switched courses, attending Yale Divinity School in 1917. But after one year in New Haven, Gordon postponed his studies to fight in World War I. Upon returning to the United States, he took up his studies at the University of Chicago, graduating with a master’s degree in divinity.

In December 1920, Gordon came to South Bend to serve as reverend of the Taylor A.M.E. Zion Church — today called First A.M.E. — located at the intersection of Eddy and Campeau Streets, just a few blocks south of the University of Notre Dame’s campus. It was one of three black churches in the city at the time (although a fourth was founded in 1923) and the only one on the mostly white east side of town. There were enclaves of black residents on the east side, particularly near Gordon’s church, but most black migrants from the South were forced to live on the west side, close to the factories. This was the situation that Gordon encountered in 1922 when he wrote and published The Negro in South Bend: A Social Study, making him one of few authors — if not the only — to tackle racism and discrimination in the city at the time.

But the contributions Gordon made to South Bend have been largely forgotten. Historical records suggest that his book was read at the time by black and white residents alike, but it went out of print and remained difficult to find for nearly a century. As David Healey wrote in his introduction to the 2009 edition of the book, “The Negro in South Bend soon disappeared, except from a rarely visited corner of the archives in the local library, the bookshelves of a few descendants of long-time black families, and at least one spineless copy on eBay.” Today, even after its republication, the book is nearly impossible to find outside of South Bend, and risks sinking back into its obscurity.

Gordon’s slim volume, which was privately published in 1922, leaves behind a legacy of documentation and advocacy, functioning as a work of journalism, social science, and advocacy all in one. It also serves as one of the few books about South Bend that provided contemporary accounts of the social workings of the city during this pivotal time. Little has been written on South Bend race relations, but nearly every one of the smattering of books, articles, reports, and theses on the topic cites The Negro in South Bend.

South Bend Before Gordon

While larger industrial cities like Detroit and Chicago have been the focus of much scholarship, not much has been written about the history of race relations and civil rights in secondary Rust Belt cities like South Bend. To the extent that South Bend’s history has been written down, it has largely focused on the experiences of settlers and people of European descent. Part of this stems from the fact that there were very few black residents until World War I, but the black history of South Bend was still rich even before the Great Migration.

James Washington

The main headquarters for the Underground Railroad in Indiana were said to be in Fountain City, a small town about 70 miles east of Indianapolis, but in the 1800s, South Bend had its share of both white and black abolitionists — including, at one point, the county sheriff. James Washington, a free black barber, was particularly instrumental, hiding people fleeing slavery in a secret room, and though South Bend never became a key stop on the Underground Railroad, a small band of abolitionists supported him in his cause.

During the 19th century, census figures indicate that the black population of South Bend was small — less than two percent of the population. This meant, Gordon wrote, that “there was no racial problem since there were so few Negroes.” In spite of the relatively low number of black residents, churches and community organizations sprung up, including the St. Pierre Ruffin’s Club, an organization for women started in 1900, the Literature, Art, and Research Club for men, and a handful of black churches within city limits. As South Bend’s black population boomed, however, the white institutions were unwilling to provide support, and these few black institutions that existed soon found themselves overwhelmed.

South Bend’s “Negro problem” as Gordon knew it was only five years old at the time of his writing. It was only after white factory workers left for World War I that black migration to smaller cities in the Midwest, including South Bend, began in earnest. With the expansion of South Bend’s industry during and immediately after World War I, the city became a much more attractive destination for black migrants from the South and other potential workers seeking factory jobs. As Gordon himself notes, the number of black residents in South Bend was swiftly rising, having doubled between 1910 and 1920 and nearly tripling between 1920 and 1922 as black factory workers sent back for their families.

[blocktext align=”right”]Gordon’s slim volume…

leaves behind a legacy

of documentation and advocacy, functioning as

a work of journalism,

social science, and

advocacy all in one.[/blocktext]The 1920s saw the rise of hate groups in Indiana, particularly the Ku Klux Klan. Although the KKK gained considerable power in Indiana politics for much of the 1920s — culminating with the election of klansman Edward L. Jackson as the state’s governor — the organization never had the same political sway in South Bend as it did in the rest of the state. Although the vast majority of the city’s population at the time was white, the substantial presence of Poles, Hungarians, and Roman Catholics — all of whom were reviled by the KKK — kept the Klan from gaining too much political power at the local level.

Although South Bend’s policies were not as outwardly discriminatory as they were in other parts of the state, racist laws and attitudes were still pervasive, and the city was a conservative place at the time of Gordon’s arrival. A 1919 South Bend Tribune editorial stated, “One of South Bend’s greatest assets in the past has been its conservatism.”

But amid this staunch conservatism were growing numbers of black migrants seeking jobs and a better life in the North. As Gordon noted, most factories in South Bend discriminated based on race in their hiring, although the Studebaker Corporation and a few others did hire black workers. It made sense that the growth in black residents was larger in bigger industrial centers like Chicago and Detroit — there were simply more jobs and opportunity there, especially given that not all factories in South Bend would hire black workers — but these factories were still major draws for black migrants seeking work.

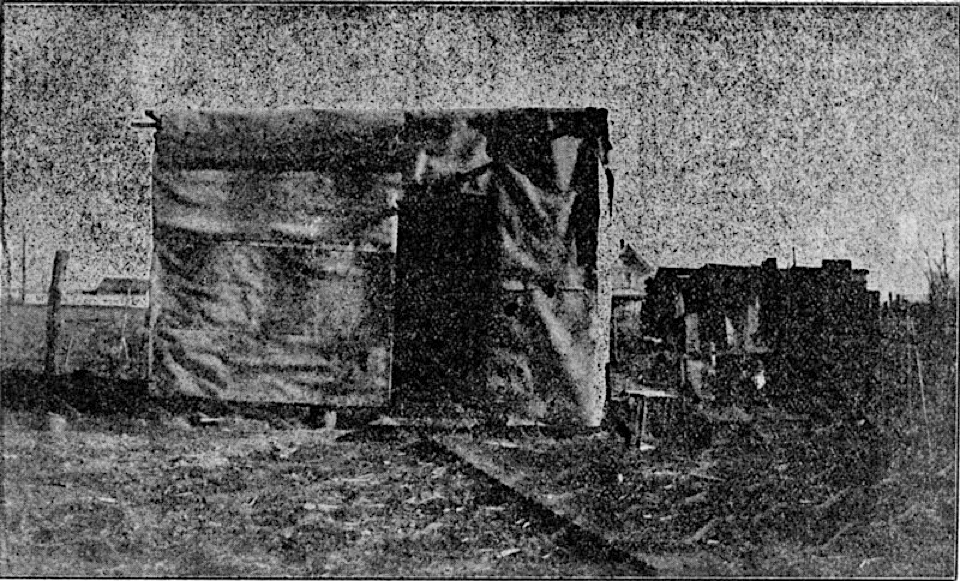

Even as black residents were moving to the city, they faced housing shortages and discrimination. At the time, black residents were only allowed to purchase homes near LaSalle Park on South Bend’s west side — a site near an industrial dumping ground. (As of 2013, it is now a federally recognized superfund site.) The homes that potential black homeowners were allowed to buy were substantially worse than homes in the rest of the city. The home that Jim and Mary Cobb moved into in the early 1920s had just three rooms with no indoor plumbing, as Gabrielle Robinson reported in her book Better Homes of South Bend. Fifty years later, this neighborhood would be home to one of the highest black populations and lowest median incomes in the city, according to the South Bend Tribune.

South Bend home of a black resident

Black residents of South Bend also faced Jim Crow-style segregation in places such as restaurants and theaters. When Jesse L. Dickinson, a state senator and civil rights activist, first came to the city in the 1920s, he encountered difficulty finding a restaurant that would serve him. “We were told there was only one place that would accept Negroes,” he told the South Bend Tribune in 1969. It was only in the 1930s that segregation in public places started to fall.

South Bend in 1920 was a city divided — ripe for someone with the interest and sociological training to study. When Buford Gordon arrived, he had plenty to write about.

The Negro in South Bend

When The Negro in South Bend was published in 1922, the city was facing turmoil: an unprecedented increase in black residents, followed by discrimination in education, and a backlash of conservatism among the city’s longtime residents. At the time of Gordon’s writing, South Bend’s black residents had very specific needs, including the need for housing, social organizations, education, and work between the black and white residents of the city.

In addition to conditions in South Bend, the Chicago race riots of 1919, which took place as he was studying at the University of Chicago, also influenced Gordon’s writing. He included a letter on the topic from the Chicago Church Federation in his appendix. Ultimately, the need for white people to understand their fellow black citizens, he writes, is what compelled him to write his book :

There are people who think that the Negro is in the same environment that the white man is, since they are living side by side in a city. They are not. … Living together, yet we may be as separate as the islands of the sea are from the main lands of the United States … Because of this common thought among many of the citizens there is but little attention paid to the Negro group in many of the smaller cities. Such has been the case in South Bend. No one wants to be cruel to the race and wants to keep it down, down in this city they are holding back the progress of the city at large. But the thing that comes before us in this volume is the need of the acquaintance of the white people with the conditions of the Negroes in general in South Bend.

One of Gordon’s central arguments is that the black church in South Bend played a central role in the social life of the black community. Being a minister, Gordon has a biased perspective that he makes no effort to mask. However, he still makes an argument for the importance of black churches in providing social services. He also took an explicit bent toward social justice in his theology, writing that “the way to save a man is to make him feel that he is a social being as well as a spiritual being, for folks are saved to live better on earth as well as in heaven.”

Gordon’s volume also presages the debate on housing discrimination that would come to South Bend and most other U.S. cities in the middle of the century. Noting that there was a shortage in housing for black migrants coming from other parts of the country to work in South Bend factories, he advocates both for the construction of proper housing in black neighborhoods and the abolition of discriminatory housing practices.

The book also notes an egregious discrepancy in the education of black and white teenagers. Even though the black population was estimated to be over 3,000, there were less than 20 black students enrolled in South Bend high schools. Gordon traces this to a culture in the South that did not enforce attendance among black students, as well as a lack of incentive for them to attend school. He proposed that the city provide more incentives for high school graduates by providing more skilled jobs that were open to black workers and hire truancy officers to ensure that people were staying in school.

Many of Gordon’s observations related to South Bend’s black population more broadly, but he noted the specific challenges that young black women in particular faced in seeking jobs and education in a smaller city such as South Bend. Black women, knowing the majority of jobs that were open to them in South Bend were in unskilled professions, either sought to leave South Bend for the larger metropolises of Chicago or Indianapolis or saw no incentive to continue with their schooling. Schoolchildren “must have a goal to reach, but this goal must be where they can see it,” he argued. Without this seed of opportunity, Gordon saw that talented black residents would either leave or be listless.

The book followed much in the same vein as W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Philadelphia Negro in that it sought to take into account both the broad issues facing black populations in a particular city and the impact that they had on individuals. Although Gordon was a minister by education and trade, he also had a great interest in the social sciences, having taken a number of sociology courses during his time at the University of Chicago. Du Bois had substantially more time and training to finish his project, so it is longer and more complete, but Gordon brought his understanding of the social sciences to his work despite coming from a somewhat less academic perspective.

The book followed much in the same vein as W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Philadelphia Negro in that it sought to take into account both the broad issues facing black populations in a particular city and the impact that they had on individuals. Although Gordon was a minister by education and trade, he also had a great interest in the social sciences, having taken a number of sociology courses during his time at the University of Chicago. Du Bois had substantially more time and training to finish his project, so it is longer and more complete, but Gordon brought his understanding of the social sciences to his work despite coming from a somewhat less academic perspective.

Du Bois’ influence on Gordon extended much further than the titles and premises of The Philadelphia Negro and The Negro in South Bend. The book also had much in common with Du Bois’ Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans, which outlined many of the same problems in the black population at large that Gordon saw in South Bend. Both writers saw a need for cities to provide greater public facilities for their black citizens, including social organizations, education at all levels, and churches.

In his capacity as reverend, Gordon preached about the social issues of the day to the patrons of his church. His March 5, 1922, sermon, titled “The Quest of Restless Souls,” addresses the racial injustice of his time. In this sermon, he spoke out against the discrimination of the time and called for a more just society. He also endorsed the Pan-African Congress and the NAACP, two of Du Bois’ most significant projects at the time.

Du Bois himself was in contact with Gordon on at least one occasion, and he even spoke at Gordon’s First A.M.E. Zion Church, on the Pan-African Congress, in January of 1922. Getting the foremost man in black political thought at the time to come to his small church in South Bend, Indiana, must have been quite the coup for Gordon.

However, Gordon was far from a Du Bois acolyte, even though the two agreed on many issues facing African Americans during the first half of the 20th century. One major point of divergence between two thinkers was Gordon’s use of Christianity in the name of social justice. When Gordon made moral appeals, he did so using explicitly Christian terms, and theology informed his work much more than Du Bois’ comparatively secular outlook.

Like most preachers, Gordon spoke in terms of salvation. His sermons often dealt with heavenly salvation, but his writing in The Negro in South Bend discussed a type of salvation that can be achieved on Earth: saving white people from racist attitudes by educating them. Perhaps his arguments in The Negro in South Bend can be best summed up in this statement, speaking to his congregation a month after Du Bois’ visit:

And the sooner that the world recognizes that the darker races of the world cannot and will not be satisfied until they take their rightful places in the world’s affairs, the faster civilization will move forward, and the better the world will be.

Gordon’s Enduring Legacy

Gordon stayed on as reverend at the First A.M.E. Zion Church until 1925, overseeing the construction of a new, bigger building to accommodate a growing congregation — the old church had been housed in a small, simple building made of cement. The very existence of the new church building was threatened, however, when the most infamous organization from Gordon’s hometown caught wind of the plans. The Indiana Klan threatened to do everything in their power to intimidate Gordon, threatening to tear down the building at night and challenge the construction of the church in court. It was only after Gordon started carrying a pistol, hired a lawyer, and had his congregation watch the construction site every night that the church was able to be completed.

First A.M.E. Zion Church

As detailed in David Healey’s introduction to the book’s reissue, Gordon left South Bend in 1925, three years after the publication of the book, to become the pastor of a church in Akron, Ohio. Gordon’s wife would later say that he moved because he thought he could “do better in some other town.” His prediction ended up being true: Gordon stayed in Ohio for several more years until being promoted to bishop of the A.M.E. Zion Church and moving to Charlotte, North Carolina, where he would spend the rest of his life.

With Gordon gone from the city, The Negro in South Bend might not have made much of an impact outside of its immediate historical period. After all, it was published privately by a person from a marginal community in a marginal place. The book’s legacy, however, far outlasted its limited original run. Despite the book’s relative obscurity today, it became hugely influential in the somewhat scant literature on race relations in South Bend.

Gordon was vehement in his fight against attempts to enforce segregation and the “color line” in every respect— education, housing, social organizations, the workforce. For one, his book advocated for equal education and social opportunities for the black and white residents of South Bend. Place mattered for Gordon — he saw that the black community of South Bend faced unique concerns as a small city, even as it suffered from many of the same concerns as the black population nationwide.

Access to public facilities for white and black citizens — one of the most substantial arguments of The Negro in South Bend — became a rallying call for activists in the years following the publication of the book. The integration of the public swimming facilities at the Natatorium on South Bend’s east side, for one, became a central fight for civil rights activists later on in the century. Black swimmers were first allowed into the facilities in 1936, although the pool had separate days for black and white swimmers until 1950, when the pool facilities were fully integrated. Today, South Bend’s Civil Rights Heritage Center is located in the former Natatorium.

A more immediate effect of Gordon’s book was the establishment of the Hering House in 1925. The Hering House was named for Frank Earl Hering, a former head football coach at the University of Notre Dame, and his wife, Claribel — local philanthropists who, after reading The Negro in South Bend, donated the money for the establishment of a community center on the city’s west side to serve the black population. The Herings may have donated the money to establish the organization, but Gordon’s role cannot be understated. His work provided the necessary direction for the establishment of the center. The Herings clearly recognized his influence, as they even asked Gordon to give the benediction at the building’s dedication ceremony.

As David Healey wrote, the Hering House more than a physical building: it was a “social force” for the city’s black community. Given that the local YMCA and YWCA clubs were closed to black residents, few opportunities were afforded to black residents before the Hering House was established. It was not without its problems and inequities — for one, five out of seven of its board of directors were white — but it was a central aspect of black social life in South Bend until it closed its doors in 1963.

Other contemporary books also shine light on the conditions of black residents of industrial Midwestern cities. S. Henri Browne, the minister of Grand Rapids’ Messiah Baptist church, wrote an article in 1913 called “The Negro in Grand Rapids” about many of the same issues that Gordon described in South Bend: unemployment, lack of access to housing, and lack of incentive to pursue a high school education among black residents. As described in Randal Maurice Jelks’ African Americans in the Furniture City, Browne noted that, much like in South Bend, the incentives to pursue education for the city’s black youth were slim, as their jobs would mostly limited to menial labor whether or not they graduated high school.

The Negro in South Bend was Gordon’s lone venture into sociology, although he wrote two other books in his lifetime. After moving to Akron, Gordon wrote Pastor and People, which focused on the organization of the church. His final book, Teaching for Abundant Living, addressed problems that pastors encountered in religious education.

South Bend black business section

Gordon served as bishop of the ninth district of the A.M.E. Zion Church until his death in 1952. Although he had been gone from South Bend for nearly three decades, the impact of his book was felt for years. The Hering House, which played an inextricable role in establishing a civic life for black South Bend residents, was the site of many meetings of the Better Homes of South Bend collective, as Gabrielle Robinson noted in her book profiling the organization that fought against housing discrimination, banding together to build houses on two blocks of unoccupied land in a white neighborhood and establish a black middle-class community away from the squalor of the industrial center. Beyond serving as Better Homes’ meeting site, the Hering House helped facilitate an environment in which black residents could organize.

Gordon’s story is important to South Bend, but there are countless other Gordons: people who change the course of history in the cities they lived but remain largely forgotten, even by residents of the same cities. Many other cities have similar stories and migration patterns to South Bend, and the phenomena described in Gordon’s book could have taken place in Akron, Lansing, Peoria, Racine, or any other industrial Midwestern city with a similar history of discriminatory policies. We would do well not to forget Buford F. Gordon.

___

Kevin Tidmarsh is a native of South Bend, Indiana currently attending school in California.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.

Hey! Wasn’t Kevin Tidmarsh a spelling champion! I seem to remember his name and face from years ago. Who knows?

Kevin,

You’ve done an excellent job of setting the historical context for South Bend’s civil rights struggles of the 60s and beyond. The book is available world-wide at http://michianamemory.sjcpl.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16827coll4/id/195/rec/9

What a beautiful article. I’m ashamed of my race for being so cruel. Thank you for sharing this beautiful article. I will keep sharing.

Mr. Tidmarsh,

Thanks so much for this beautiful article! My name is Catherine Gordon and I am the granddaughter of the late Bishop Buford Franklin Gordon. My father (Rev. Charles Gordon) was the son of Bishop Gordon.

I googled my grandfather’s name and came across your article. It is so informative and rich in history!

My grandfather passed before I was born. There’s so much I didn’t know about him. You’ve really blessed me today!

Ms. Gordon,

I’m so glad you found the article, and even more you enjoyed it! This is the absolute best outcome I could have hoped for with this article, and I’m completely humbled by your response. In the event that you see this, I’d love to talk about your family’s history- send me an email at [email protected].

-Kevin