The following is an excerpt from Where the River Burned, by David Stradling and Richard Stradling, copyright © 2015. With permission of the publisher Cornell University Press. Used by permission of the publisher, all rights reserved.

By David Stradling and Richard Stradling

On April 22, 1970, schoolchildren from around metropolitan Cleveland sat in their classrooms and wrote to Mayor Carl Stokes. Over the next few days, hundreds of letters poured into City Hall, where staffers read, sorted, and distributed them for responses. On some, they circled key words (pollution, in particular), and on others they scrawled numbers at the top, probably indicating which form letter should be sent out in reply. Many of the children asked for information about the city’s environmental policies; others asked for a photo of the mayor, who was, after all, quite famous. Despite the diversity of the letters sent on the first Earth Day — some came from the city, others from the suburbs; some from young children, others from teenagers — altogether they described an environmental crisis in remarkably familiar terms, and they tended to discuss what had become distressingly familiar topics. They described a city in which heavy air pollution threatened lives — children’s lives — and water pollution fouled Lake Erie’s beaches and killed its fish. For these children, the terrible pollution raised questions about the future of Cleveland and its residents, and even of the nation as a whole.

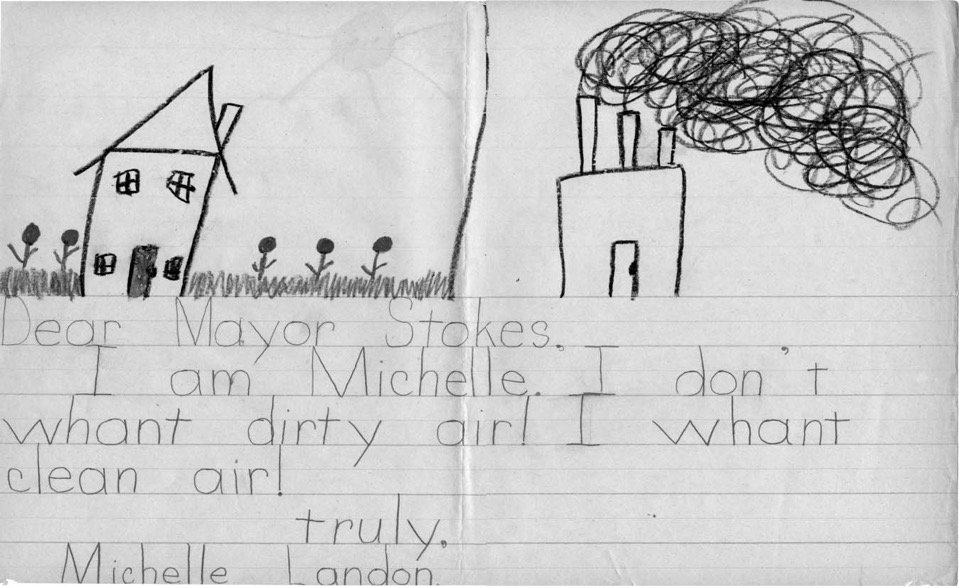

Most of the letters were short and to the point. For instance, all students in one second-grade class wrote the identical letter, which reads in its entirety: “We do not like dirty air. We want our air to be clean so we can be healthy. Please make our air clean.” Although they were practicing penmanship as much as participatory democracy, these students’ letters took on special meaning because they came from the Hodge School, on the East Side, just four blocks from the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company’s massive, coal-burning, smoky lakeshore power plant. These kids had good reason to worry about their own health, even in second grade. At other elementary schools, children wrote their letters on oversized paper with space at the top for drawings. Here the youngest students exerted some freedom of expression, and many made liberal use of black crayons; dark smoke curled out of factories and trailed behind airplanes. Some imagined solutions, including a great lid that could be lowered onto polluting factories, trapping the smoke — a poignant mix of childish fantasy and dead seriousness.

Many of the suburban children who wrote to Mayor Stokes complained about pollution as an urban phenomenon. The first-grader Michelle Landon used green and black crayons to contrast her beautiful middle-class home in Lyndhurst with the heavily polluted environment of Cleveland. Carl Stokes Papers, container 75, folder 1435. Courtesy of Western Reserve Historical Society.

The brainchild of Gaylord Nelson, Democratic senator from Wisconsin, Earth Day was a national event featuring teach-ins on college campuses, at schools, and in public parks. There were lectures, demonstrations, and opportunities to clean up green spaces, waterways, and schoolyards. An estimated twenty million Americans participated in Earth Day in some way or another, and the event became a watershed for the environmental movement, which was growing rapidly. A great range of environmental issues gained attention during Earth Day, but air and water pollution were the most important nearly everywhere, including Cleveland, where despite the fact that Mayor Stokes declined to participate personally, citizen involvement in what the city called “Environmental Crisis Week” was extraordinary. Residents of metropolitan Cleveland had long been acutely aware of their city’s pollution problems, but in case someone had missed the other clues — the smoke shroud, the fouled beaches, the burning river — on April 20, Monday-morning commuters on Interstate 71 were greeted by a banner hanging from the W. 25th Street overpass: “Welcome to the 5th Dirtiest City.”

The Earth Day letters reveal how well educated students had become on environmental issues. Fifteen-year-old Andrea Rady wanted Stokes to know that she and other students at suburban Westlake High School had “conducted several studies on the pollution problem in Cleveland.” Her letter discussed pollution broadly, but it mentioned just one example of the problem: the Municipal Light plant, a smoky, coal-fired power station on the city’s East Side lakeshore, not far from the Illuminating Company’s plant. As Rady put it, the plant was “both an eyesore and a health hazard to anyone coming within 1 mile of it.” Rather than fault Muny Light itself, Rady blamed the pollution on Stokes. “For the past four years, you and your officials have been arguing over petty legalities while pollution continues to strangle our city. To my knowledge, several solutions have been proposed, but none have gotten past your desk.” Rady’s portrayal of Stokes as the impediment to progress wasn’t accurate, but Muny Light was owned and operated by the city, and so she was right to claim that Cleveland officials deserved special blame for the plant’s smokiness. The pollution from Muny Light had earned attention from the press for nearly a decade, and the Stokes administration had been working on solutions. We might wonder, though, why Rady decided to single out the Muny plant. After all, she was not among the Clevelanders who lived within a mile of the plant, and given that she resided in a middle-class suburb to the west of the city, she wasn’t likely to come within a mile of it regularly either.

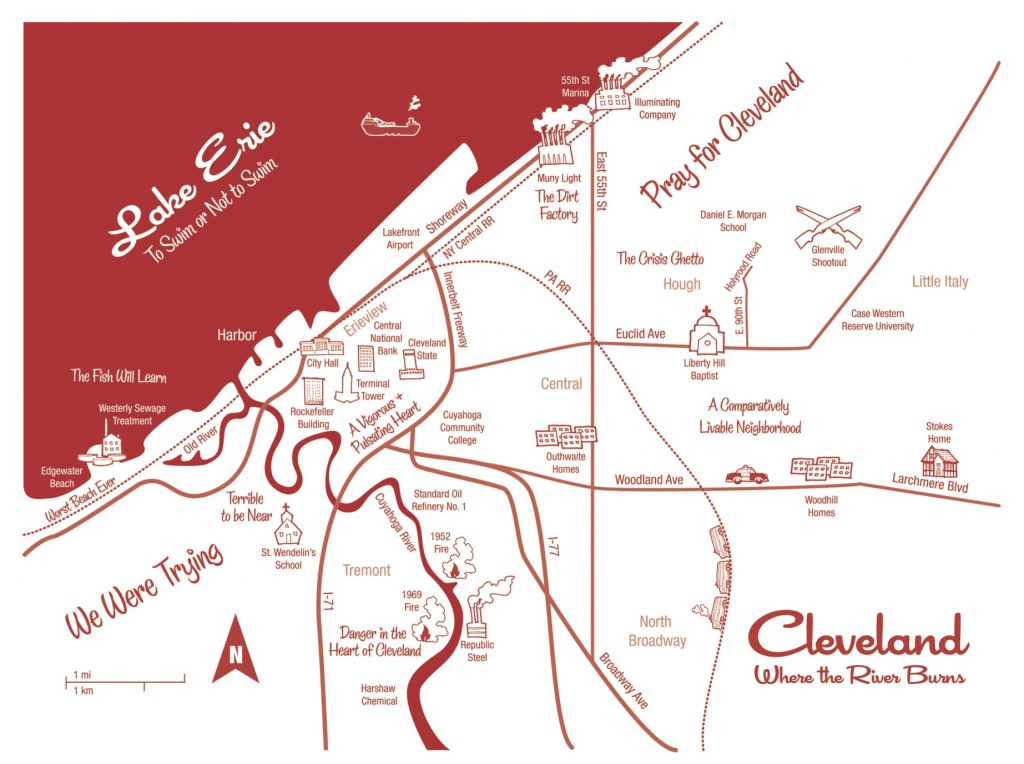

Map design by Jenn Hales

Many students complained about Muny Light on Earth Day. Rady’s classmate Robert Tasse wrote Stokes with the understanding that the mayor was “not responsible for everything that goes on” in Cleveland, but he hoped to encourage action, as so many writers did. He asked Stokes to “pressure some (if not all) of the growing industries in Cleveland, like Republic Steel, Muny Light Plant and Edgewater Park” — a remarkable list, mostly because it didn’t include any actual “growing industries.” Despite a series of capital investments in new facilities in the postwar decades, Republic Steel hadn’t grown in years. Perhaps Tasse inferred that the mill complex along the river was growing because of the constant media attention to its incredibly smoky stacks and its heavy contribution to water pollution in the Cuyahoga. Edgewater Park was just that — a park along Lake Erie west of the mouth of the Cuyahoga and, perhaps more important, adjacent to the Westerly Sewage Treatment Plant. Edgewater included a beach that in recent years had featured signs warning against swimming due to high coliform bacteria counts. During the summer before Earth Day, the beach had gained significant press attention as the Stokes administration attempted to clean the shore and nearby waters, at least enough to allow safe swimming at the park. Like Edgewater Beach, the Municipal Light plant was consistently in the news in the late 1960s, the focus of concerted efforts to improve air quality in the city.

Tasse’s letter confirms the obvious: students, like adults, learned about their environment from the news as well as their lives. Undoubtedly, discussions in school that week, which at Westlake occurred in both biology and English classes, affirmed this list of problematic places; Edgewater Park, Muny Light, and Republic Steel were well-established targets of environmental activism. But even the letters that include no specific target of concern confirm that for most students — for most Cleveland-area residents — the most pressing environmental issue was pollution, which they tied directly to industry. They also expressed a growing urgency concerning political action. Shannon Havranek, a junior in Maple Heights, a working-class suburb south of the city, wrote, “Sitting around and talking about pollution doesn’t help a dying lake and atmosphere. Act now. Make the industries improve their sewage disposal. Spend more money on pollution control. Impose heavier fines on littering.” In the minds of children, the path forward seemed so clear.

The letters capture the sense of environmental crisis in 1970 and, somewhat less clearly, an understanding of the ongoing urban crisis. Pollution emanated mostly from the city’s core, especially the riverside mills and the lakeside power plants, but the children wrote mostly from surrounding suburbs — Westlake, Maple Heights, Cleveland Heights — a reminder of how much suburbanization had already reshaped the metropolitan area. Although the letters said little on the subjects of concentrated poverty, inadequate housing, crime, and racial inequality — all topics that probably seemed inappropriate for Earth Day letters — many students wrote with an understanding that Cleveland’s problems could not be solved through the haze of pollution. The city was engaged in major urban renewal projects, putting special emphasis on reviving the central business district, part of the effort to speed the transition to a service city. But as Havranek put it succinctly, “The new improvements in downtown Cleveland will not be seen through the pollution.” The letters raise serious questions: would the city survive the seemingly impossible confluence of crises described in the letters? What would become of a city suffering simultaneously under the weight of industry’s wastes and the wrenching displacement caused by industrial decline?

The letters capture the sense of environmental crisis in 1970 and, somewhat less clearly, an understanding of the ongoing urban crisis. Pollution emanated mostly from the city’s core, especially the riverside mills and the lakeside power plants, but the children wrote mostly from surrounding suburbs — Westlake, Maple Heights, Cleveland Heights — a reminder of how much suburbanization had already reshaped the metropolitan area. Although the letters said little on the subjects of concentrated poverty, inadequate housing, crime, and racial inequality — all topics that probably seemed inappropriate for Earth Day letters — many students wrote with an understanding that Cleveland’s problems could not be solved through the haze of pollution. The city was engaged in major urban renewal projects, putting special emphasis on reviving the central business district, part of the effort to speed the transition to a service city. But as Havranek put it succinctly, “The new improvements in downtown Cleveland will not be seen through the pollution.” The letters raise serious questions: would the city survive the seemingly impossible confluence of crises described in the letters? What would become of a city suffering simultaneously under the weight of industry’s wastes and the wrenching displacement caused by industrial decline?

Cleveland’s first Earth Day is of special interest because in addition to suffering from problems common around the nation — pollution, litter, and even the proliferation of rats — the city had garnered an international reputation for its especially acute environmental crisis. In the years leading up to Earth Day, Cleveland appeared in the national press for a variety of reasons. Some of the attention was positive, especially in 1967, when it became the first large city to elect an African American mayor. But as the nation’s urban and environmental crises deepened, Cleveland attracted mostly negative attention. The city was struggling to clean up Lake Erie, its greatest natural asset and the most imperiled Great Lake. In 1965, the national press detailed racism’s consequences when the U.S. Civil Rights Commission held hearings on housing, schools, and employment discrimination in Cleveland so that it might understand the plight of African Americans in a typical northern city. Over the next three years, Cleveland experienced two intense riots, one before and one after Stokes entered office, both of which drew attention to the physical realities of the decaying ghetto. And the events of the summer before Earth Day, including the passage of a new air pollution ordinance, the creation of a water pollution control plan, and the Cuyahoga fire, had kept urban environmental issues in the news. In sum, by the time April 1970 rolled around, Cleveland had become emblematic of the intertwined urban and environmental crises. As Tasse put it in his letter to Stokes, “not every city can say they have a river that catches on fire.” Or, to put it another way, Cleveland had become the city “where the river burns,” just as the Plain Dealer had predicted.

___

Copyright © 2015 by Cornell University Press. Used by permission of the publisher, all rights reserved.

Banner photo, of 1952 Cuyahoga River fire, courtesy of Teaching Cleveland.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.