This essay is an excerpt from our forthcoming Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology (Belt Publishing, June 2016).

By Sarah Carson

In 1997, an international incident was brewing.

The World Wrestling Federation’s Shawn Michaels and Hunter Hearst Helmsley had declared war on their Canadian rivals, the Hart Foundation.

Their new faction, Degeneration X, was set to battle the Harts just 45 minutes west of where I — all of thirteen years old — was living with my mother and sister in a suburb of Flint, Michigan.

My mom, a sensible woman who did not waste her Monday nights watching grown men pretend to fight on the USA Network, offered me a deal.

D-Generation X – Triple H and Shawn Michaels

She’d be happy to pay for me to watch this ridiculous display — in fact she’d be happy to pay for me and a friend and a friend’s parent to watch it — if only the friend’s parent would do the driving and chaperoning.

My mother would, under no circumstances whatsoever, sit through a professional wrestling event.

“Deal!” I thought. “No problem! Perfect!”

I got on the phone to my best friend and relayed the offer: an all-expenses paid trip to the defining moment of our young wrestling fandom. Sexy boy himself Shawn Michaels! Sweet chin music! Triple H and the Pedigree! Those despicable Canadians coming through the curtains, off the ropes, a folding chair to the back of their heads! We could see it all! All we needed was a ride.

I heard my friend put down the phone and call to her mother in another room beyond the phone cord’s reach.

“I don’t know how to get to Lansing,” her mother said. “I’ve never been farther west than Durand.”

There was quiet as my lungs, my friend’s lungs deflated.

My friend pleaded. She conveyed our desperation.

But her mother was stalwart: “No way,” she said. “I am not leaving Flint.”

* * *

It’s been nearly two decades since I did not see Shawn Michaels and Triple H defeat the Hart Foundation, and nearly a decade since I packed my things and left my hometown, left my family and friends and elementary school and baptismal church and favorite playground and roller-skating rink and front-porch-of-my-first-kiss.

[blocktext align=”left”]“No way. I am not

leaving Flint.”[/blocktext]And it’s taken just about that long for me to understand why my friend’s mom refused to take us to Lansing that day.

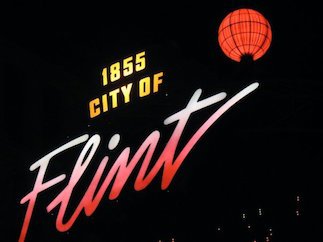

I’ve lived in Chicago for nearly ten years, and if the people I meet now have heard of Flint, they’ve heard of violence, they’ve heard of lead-poisoned water.

Of course they’ve heard about the birth of General Motors, the Great Sit-Down Strike, but mostly they’ve heard about plants closing, homes set on fire, generations of families out of work.

But what they’ve not heard is that no one leaves home unless leaving home is a necessity, unless home is a set fire burning too hot to go back.

What I most struggle to explain to the people I know now is what I think people from the Bronx, from Chicago’s South Side, from Texas, from Mexico must also struggle to explain — that there’s a kind of pride in being from somewhere other people do not want to be from, that there are entire families, blocks, neighborhoods who’ve never thought about leaving, whose identity is rooted in the fact that they’ve stayed.

My family is one of those families, whose tree is almost entirely rooted in thirty square miles, who was Vehicle City before Vehicle City was a thing.

My great-grandfather built Buicks. My father’s father built Buicks. My father built Buicks when he was not arguing with the foreman about his Ted Nugent poster.

My grandmother built Buicks. My mother’s father won a lapel pin by building Buicks, by having the cleanest station in the spring shop.

Credit: Joe Clark, via Wikimedia Commons

When my mom first showed me Roger and Me, I never dreamed of becoming an expatriate, an out-of-state resident, an absentee voter, a girl in search of a hometown.

Except that home became a place unrecognizable from the photos my mother keeps in neatly-stacked boxes, except that home welcomed me into its warm, wet mouth just to spit me as far as its tongue could launch me. Except home looked me in the eyes and asked me to leave.

* * *

It starts with a dog.

Maybe it starts a little before the dog. Maybe it starts in college, where I first learned that it could be done, that survival away from home was possible, even if it meant getting used to people who didn’t know the difference between a Detroit and a Flint coney, who have no moral qualms about financing a Toyota, who have never missed a phone bill in their lives.

But mostly it starts on my grandma’s living room floor, just north of the Pierson Road Meijer that has since been torn down to the pavement, just west of the Ramada Inn that has also been leveled, not far from a Denny’s that is no longer there.

It starts 22 years after I was born at Flint Osteopathic Hospital, 24 years after my mother was also born at Flint Osteopathic Hospital, 61 years after my grandmother was born at home where Lavelle and Flushing Roads meet.

It starts just after I had come back to Flint from my first failed attempt at adulthood in Southeast Michigan, after my mom had paid the adoption fees for a sad-looking hound dog picked up by Genesee County Animal Control, after I flipped through a Bible trying to find a name worthy of a dog whose story was as epic as the story of the patriarchs.

The dog had been found abandoned in a house on the east side, in what I liked to imagine was a warm, Sears Roebuck bungalow, one of the thousands of houses erected quickly for factory families, families who’d come north on the promise of work on the assembly lines, not far from where my dad had spent thirty years behind the controls of a crane, hoisting dyes for Regals and Sport Wagons, near where Grandma had moved into her first apartment with Grandpa after leaving her first husband alone on the farm.

The dog needed a name that said all this each time he was called. He needed a name that would always bring him back to where he came from.

Abraham? The father of many nations?

David? The giant slayer? The boy who’d become king?

No, this dog wasn’t a ruler as much as a harbinger, a marker of a moment, carrying with him a warning about how the past becomes us, takes us over.

I named him Amos, after God’s man in the fields, the watcher of fig trees with an admonition for all those who’d listen — a warning about exile, about repeating the past, about a way of life that was not coming back.

* * *

Amos and I only looked at two houses before signing our very own lease on Flint, Michigan.

The first was in Little Missouri, just east of the expressway, owned by a little elderly couple that lived next door and seemed too interested in how much time I might be around to help them change light bulbs.

Credit: Michigan Municipal League (https://flickr.com/photos/michigancommunities)

The second, on Lexington Avenue, half a block from the Grand Trunk bridge, across from a dime store, lumber yard and muffler shop that are all vacant real estate now, came with a rent-to-own contract and the promise of a chain-link fence for the dog.

The tiny one-bedroom had high vaulted ceilings where the owner, Darwin — another never-left-Flint kind of guy who’d worked as a detective before opening his own private investigation business — had drywalled over the attic. Grapevines crawled up a back fence that separated our lawn from a junkyard. Oak trees grew the perfect distance from each other to hang a hammock. Two steel poles marked where a clothesline once stood.

Darwin told me he’d paint the house whatever colors I liked. He wrote our lease on a loose piece of floral stationary.

“What’s a good-looking girl like you doing moving into a house alone, anyway?” he asked as he handed me the keys.

“I’m not alone,” I smiled. “I have Amos.”

Amos followed his nose around the backyard and began digging a path under the fence.

* * *

In Flint in 2006, the year Amos and I moved into our one-bedroom house, the city-data.com crime rate was 1089.6. That means that — figuratively — for every 100,000 people living in Flint, 1,089 of them would have been affected by a serious or violent crime. This is more than three times the U.S. average of 294.

In 2006, 54 people were murdered in Flint. 2,246 were assaulted. 3,058 houses were burgled.

On nights when Amos and I would go eat TV dinners with my grandmother, after she’d cleared the plates, after she’d lit up a menthol Smoker’s Choice, after Amos had his own snack of cheerios and peanut butter, Grandma would grab the remote and announce, “Let’s see who got killed today” as she turned on the evening news.

[blocktext align=”right”]Grandma would grab the remote and announce,

“Let’s see who got killed today” as she turned

on the evening news.[/blocktext]So perhaps I should not have been surprised the first time I heard the rumor about masked men creeping through the neighborhood.

I’d only been in my house a month when so-and-so told so-and-so who told so-and-so who told me about the retired bus driver with the grown children in Florida who sometimes did her cooking naked with the back door open — how she hadn’t heard the knocking at her door, so the masked men had let themselves in through a window. They made off with her jewelry and her television and promised not to hurt her if she didn’t call the cops.

Soon after the same story was being told about Mercedes in the house across the street whose toddler son spent all day running naked back and forth across the yard — sometimes through the sprinkler, sometimes for no reason at all. She had opened the door for the men and let them take what they wanted.

Whether they actually had pistols or were only pretending by holding their fingers taut inside their jacket pockets was unclear.

But each morning they were at a new house, coming to the back doors rather than the front.

“It’s your dog that’s kept them away from you,” the neighbors told me. “They know you’ve got a dog and don’t want to mess with him.”

It was a comforting idea, but I didn’t buy it.

On the north side, both of my aunt and uncle’s dogs had been shot in their front yard when masked men had come calling. The only difference, I figured, was that the masked men who’d turned up at my aunt and uncle’s had an agenda.

I was sure our masked men were also people who had never left Flint. Being anything else required a plan.

* * *

This, of course, had all happened in summer, when everyone knows things are crazy, when everyone expects a little drama, a little violence, a little heat-induced-stupid followed by a lot of summertime-dumb.

![Faygo [credit: Brian Mulloy (https://flickr.com/photos/landlessness)]](https://beltmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/8177335498_3db5a68ea5_o-450x450.jpg)

Faygo [credit: Brian Mulloy (https://flickr.com/photos/landlessness)]

I took a job selling Faygo to party stores up and down Saginaw Street and Linden and Corunna Roads. I spent my breaks at work writing poems in the cab of the van, dispatches from grocery store backrooms and tractor-trailers full of soda.

Amos and I worked to fix up our little bungalow. I retiled the kitchen floor. I wallpapered the bathroom. Amos learned not to pee on the rug.

Then in January some guys threw a chunk of concrete through the Faygo van window and stole my cell phone and purse while I was in a store taking an order.

The Sikh brothers who owned the place let me watch the whole incident on their closed-circuit recording system.

“Such a shame,” they said, shaking their turbaned heads.

One night in February, while Amos and I sat curled on the couch watching Judge Judy tell two feuding roommates what was what, I heard footsteps on my front porch and peeked through the blinds to see a stranger in a fedora trying to get an eyeline into my window.

Bolstered by Judge Judy’s no-nonsense spirit, I called, “What do you want?” through the blinds.

“Is Mercedes here?” he yelled back.

Before I could answer, a police SUV appeared at the curb. Two officers made their way up my sidewalk. They slammed the stranger against the glass of my storm door and ordered him to spread his legs.

“Do you know this guy?” a cop called to me through the closed window.

“No,” I replied.

“Make sure your door is locked,” the cop instructed.

I don’t know what happened after that. It didn’t seem in my best interest to watch.

* * *

One Christmas, years after I had moved away from Flint, I asked Grandma to tell me the story of how she met Grandpa.

She told me her mother had wanted her to marry a guy named Howard, whose family had a large farm, who could provide a good life for Grandma.

And Grandma did marry Howard, but Howard was annoying. So Grandma left him and started working at Buick during World War II, when the factory was co-opted to make airplane parts rather than cars. Grandpa worked on the line with her. They started flirting. Then dating. Then they moved in together even though Grandma was still technically married to Howard. She divorced Howard and married Grandpa, and they bought a house together in Beecher — a neighborhood on the north end of Flint, a neighborhood Michael Moore made famous in Bowling for Columbine with the story of Kayla Rolland, the youngest school shooting victim in United States history.

Grandma told me about the house, how at times they had crammed more than ten people into its two tiny bedrooms, how the church had given them piles of free dishes that didn’t match.

She told me about the 1953 tornado that leveled that house. How Grandpa, unable to get past the downed trees on Belsay Road, had abandoned the car and run home on foot to find Aunt Anna thrown clear across the yard onto the roof of the chicken coop.

She told me how the whole family had slept in a tent in the yard until they could afford to get the house fixed.

She paused.

Then she said, “You know, this town just isn’t the same town as it used to be.”

* * *

By spring of my first year back in Flint, I’d made a habit of only putting a couple of dollars of gas into my car at a time and constantly running the gas tank dry.

One night I was on my way to a downtown pop-up art show when I couldn’t get the car to start. I grabbed a gas can and started walking down Fenton Road toward the Stop and Shop.

It was pitch black. The streetlights that worked burned faint orange. I passed a boarded up muffler shop, a boarded up used bookstore.

Despite the many reasons I had to be, though, I still don’t remember being afraid.

The masked men, the police on the porch, the stolen cell phone — none of it had been particularly frightening.

Even the night I called the cops because I could hear someone breaking out car windows down the street, and the 911 dispatcher laughed at me for calling, I wasn’t particularly scared. I was just tired. Just tired and wide awake.

Then that night as I rounded the corner of the library annex, I heard the sound of grown men yelling. Then came the pop-pop-pop of gunfire. Then the sound of tires squealing, of someone getting away.

I curled myself in the library doorway for what seemed like forever, sure that they’d return, that they’d need to dispose of the witnesses.

That night at home, I scratched Amos’ belly in the darkness, and I thought of my friend’s mom who refused to take us to see Shawn Michaels.

But even then I hadn’t understood why she hadn’t wanted to take us downstate, why she’d never left Flint, why so many of us had never tried to live anywhere else.

Only years later did I realize that the violence, the strangers on the porch, the police who didn’t come when called, the gunshots — they were scary, and they were dangerous — but they were no more scary or dangerous than what could be out beyond the city limits.

At least here we knew what we’d gotten ourselves into. The streets, the neighborhoods, all the unspoken agreements we made when we walked down the sidewalk were familiar.

[blocktext align=”left”]In Flint, the limits were clear. The boundaries established.[/blocktext]Maybe there were other places out there where you didn’t have to take cover in a library doorway just to fill a gas can.

But at least I knew the library doorway.

How would I ever find the right doorway to duck into someplace else?

In Flint, the limits were clear. The boundaries established.

Maybe it was not the same city I’d been born into, the city I’d been promised. But it was a city I knew how to navigate, even if navigating meant running for my life.

* * *

I only eventually began thinking about leaving the night I met the masked men myself.

It was spring, and it was dark outside. I hooked Amos to his leash for a walk, stepped out onto the sidewalk, and there they were: carrying a television across my neighbor’s lawn.

[blocktext align=”right”]I locked eyes with one of them. We both paused.

Then I turned around and walked back inside.[/blocktext]I locked eyes with one of them. We both paused. Then I turned around and walked back inside.

I turned out all the lights. I did not call the cops. But I decided I liked my things too much to let other people break in and sell them for whatever they were selling other people’s things for.

Darwin was pissed when I told him Amos and I had found an apartment in Chicago.

“I wouldn’t have put up a fence,” he said. “I wouldn’t have painted, installed the carpet.”

“I’m bored,” I told him, too proud to admit defeat.

“What about the rec center?” he said. “Do you know how to play pool? I’m sure you could meet some people your age. A nice guy.”

But it was over. It had been twelve months.

Again and again, the city seemed to be saying: “Go.”

* * *

In Chicago, Amos and I moved into a neighborhood we thought would be a lot like Flint — working class, populated with families and young people looking for an inexpensive place to stay, in need of a new coat of paint.

But Chicago was nothing like where we’d come from. It was split by ethnicity, by socioeconomics, by baseball teams. There was no swapping of shop stories, no common connection born out of hard work — first in the factory, then in the streets — no arguing about who was from Chicago and who wasn’t.

Chicago pride was different. Anyone could have it — not like in Flint where pride was hard earned.

One night I went to at an open mic at a coffee shop just north of the city and read a poem about that man in the fedora who showed up on my porch looking for Mercedes.

When I was through, I was approached by a sweet old lady, a graduate of Harvard, a resident of the uber-rich North Shore, the founder of one of Chicago’s longest-lived literary magazines.

“It’s a different life, isn’t it?” she said to me.

“It’s a different life, isn’t it?” she said to me.

I smiled. And I was overcome with loneliness. I wanted to be home more than I’d ever wanted to be home before.

It was a different life, indeed. We were only four hours down the road from Flint, but we were so far from home it was scary — far scarier than a couple of guys carrying a TV in the night.

But we learned. We adjusted.

And I started telling my story to anyone who’d listen.

I talked about fires. I talked about factories. I talked about family.

I promised I never would have left except that home had become unrecognizable, a question mark.

I started playing with a theory about what it meant to leave, about all those others like me who I’d meet in Chicago, in Kansas City, in California.

I started wondering if there weren’t only three kinds of people from Flint: those who’ve always been there, those who’ve come back, and those who’ve gone.

I started wondering if Amos and I weren’t meant to be all three.

___

Order Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology here.

Sarah Carson was born and raised in Michigan but now lives in Chicago. Her poetry and short stories have appeared in Columbia Poetry Review, Diagram, Guernica, the Nashville Review, and the New Orleans Review, among others. She is the author of four chapbooks, and two full-length collections, Poems in Which You Die (BatCat Press) and Buick City (Mayapple Press). Sometimes she blogs at Sarahamycarson.com.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.