By Sharon Bloyd-Peshkin

Photos by Alec Bloyd-Peshkin

It’s a cold, grey, blustery March morning on Chicago’s near north side. Taxis, delivery trucks, and luxury vehicles swoosh along Grand Avenue and Orleans Street, kicking up road salt, honking and jockeying for space as they pass condo buildings, self-storage facilities, coffee shops, and investment firms.

River North, promoted by the city as “the go-to district for those who appreciate fine art and design,” has undergone an almost complete transformation in the past four decades, from a place of manufacturing to a locus of consumption. Long gone are most of the factories and the blue-collar workers who once gave this part of the City of the Big Shoulders its brawn; in their stead, the neighborhood now warehouses workers of a white-collar sort, and the shops, restaurants, bars and services that supply their more patrician needs.

But in the shadow of the new construction, an older, three-story building remains: Clark & Barlow Hardware, a business that served Chicago’s construction, manufacturing, and railroad industries for more than a century. It’s a hardware store where men in Carhartts who actually wear them to work line up at the counter to request tools and parts that aren’t stocked by the Ace Hardware down the street or the Home Depot across town; a place when the salespeople swiftly turn to the shelves behind them and extract those obscure items; a place where many employees have worked for their entire adult lives because, they say, they feel like a family.

But in the shadow of the new construction, an older, three-story building remains: Clark & Barlow Hardware, a business that served Chicago’s construction, manufacturing, and railroad industries for more than a century. It’s a hardware store where men in Carhartts who actually wear them to work line up at the counter to request tools and parts that aren’t stocked by the Ace Hardware down the street or the Home Depot across town; a place when the salespeople swiftly turn to the shelves behind them and extract those obscure items; a place where many employees have worked for their entire adult lives because, they say, they feel like a family.

A place that is closing.

LIQUIDATING TO THE BARE WALLS

Sale ends soon

The signs outside are unmistakable, from the banners flapping in the wind to the trucks pulling up at the loading dock to cart away deeply discounted merchandise. In the front hallway, the steel shelves are for sale, $25 per section. The hard hats are $5 each, final. Interested in the wood display cabinets? Make an offer.

Customers at Clark & Barlow.

Angela Mucci, 64, sits in the first-floor office, processing some of the markdowns. She’s worked at Clark & Barlow for more than half her life, starting at the downtown location, 123 W. Lake Street, which was displaced in 1980 by the soon-to-be-built State of Illinois Center (later renamed the James R. Thompson Center). She fondly recalls the variety of tasks she performed there, from patching together phone calls on the second-floor switchboard, to sending customers their change and receipts in metal cups that sped along an overhead wire. A frame containing two black-and-white photographs of the Lake Street location hangs above her desk.

But she’s rarely at her desk — one of the reasons she has worked here so long. Rather, the soon-to-be-grandmother spends her work hours sending invoices, ordering out-of-stock items, and pushing carts and even brooms. “I don’t want to sit in an office,” she says. “I want to work like this.”

The other reason is the people, she says, starting with Joseph J. Sullivan, who owned Clark & Barlow for 46 years until his death in 2010. “It was a good place to work, and he was a good boss,” Mucci says, pointing to Sullivan’s photo on the wall. “It was a place that you really wanted to stay. It was like family.”

In fact, for many people it really was family. Two of Sullivan’s six children, Teri and Judy, worked at Clark & Barlow for decades. Mucci applied for a job because her sister, Sophie, worked at Clark & Barlow. Sophie met her husband, Marty, there. Many employees worked alongside their siblings and cousins. People stayed until they retired, and sometimes until they died.

In fact, for many people it really was family. Two of Sullivan’s six children, Teri and Judy, worked at Clark & Barlow for decades. Mucci applied for a job because her sister, Sophie, worked at Clark & Barlow. Sophie met her husband, Marty, there. Many employees worked alongside their siblings and cousins. People stayed until they retired, and sometimes until they died.

Now long-time employees who once worked together to stock the shelves are endeavoring to empty them. “It was a great work environment,” says Michelle Diaz, 45, who began at Clark & Barlow in 1991 and is now a manager.

Diaz, whose mother, sister, daughter and cousin followed her to Clark & Barlow, is one of six remaining employees, down from 23 when the building and company were sold in 2012, and more than 50 when she started working here. She recalls her first boss, John Patdu, who came from the Philippines in 1972 when he was 24 years old. Patdu walked into the Lake Street location and saw “a bunch of old guys working there,” Diaz says, but he applied for a job anyway and was hired in accounts payable. Patdu stayed for 40 years. “Clark & Barlow was my first job and my last job,” says Patdu, now 68, who retired after Joe Sullivan died.

The Chicago Tribune obituaries tell similar stories. There’s Herbert Christiansen, who worked for Clark & Barlow for 71 years until his retirement at age 90; and Harold Schroeder, who began as a stock clerk right out of high school, became a buyer, and retired at age 65. They and other former colleagues are fondly remembered by the employees who remain during these final days.

Check it out.

70% off box price

ALL SALES FINAL

Don Schelberger considers himself a recent hire, having worked at Clark & Barlow for only 15 years.

“I’ve only been here 15 years,” says Don Schelberger, 62, who works behind the counter. It took him about a year to figure out where everything was stashed on the shelves, but now, when a customer requests an item, no matter how unusual, “I can go any place in the building and know where it’s at.”

Over the past decade, he’s watched the clientele change. At first, most customers were contractors, railroad laborers, and construction workers. Then the people who lived in the newly built condos started coming in. But the main client base remained those in the building trades.

“Hey, Dan. What time do you leave in the morning?” he asks Dan Mogan, who commutes in from the south suburbs before the store opens at 6 a.m.

“Five,” replies Mogan, who has worked for Clark & Barlow for 33 years. “There’s always someone outside waiting to buy something.”

Mogan, too, applied for a job because his brother worked there. “I didn’t know much about hardware,” he admits. But after stints on the dock, at will call, and in shipping, he learned where everything was squirreled away and started working behind the counter.

The counter at Clark & Barlow was the front line for finding all manner of uncommon hardware. “There is no other place you can go and say, ‘I need this screw,’ and they know exactly where it is and will sell you one of them,” Diaz says, pantomiming a customer holding up a singular object. “We were still one-on-one. We were more personal. We were known for our customer service.”

Now customers poke around areas that previously were restricted to employees like Schelberger and Mogan. “It’s strange watching people wandering through,” Diaz says. They paw through the shelves, brush dust off old boxes, squint at unfamiliar parts. They ask whether they can still get a particular tape or tool or trowel. “We’ve been pulling things out that’ve been buried for the past 20 years,” Schelberger says.

Sheldon Holden, 55, an airport baggage handler who lives in Chicago, came in when he saw the signs outside. “I drove past here a week ago and I thought they were just having a big time sale,” he says. “Then I looked at the signs real good and thought, ‘Wait a minute; they’re going out of business.’”

Sheldon Holden, 55, an airport baggage handler who lives in Chicago, came in when he saw the signs outside. “I drove past here a week ago and I thought they were just having a big time sale,” he says. “Then I looked at the signs real good and thought, ‘Wait a minute; they’re going out of business.’”

Holden recalls visiting Clark & Barlow with his father when he was a child, and becoming a regular customer when, as an adult, he owned an older home. “If you had something in your house that dated back to the ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s, you could probably go in there and get something to replace it. You can’t do that at Home Depot,” he says. He also came in for advice. “If you was tackling a project you thought was hard, after you talked to them, it turned out it was simple.”

“I’m going to miss the service,” Holden says. “This was the Rolls Royce of hardware stores. It was the last of the Mohicans.”

[blocktext align=”right”]“I’m going to miss

the service. This was the Rolls Royce of hardware stores. It was the last

of the Mohicans.”[/blocktext]That kind of customer satisfaction is what made working at Clark & Barlow attractive to Teri Sullivan, one of the owner’s daughters, who worked for a car rental company before taking a job at the store in the mid-1990s. “The hard-to-find things, oh yeah, they’d come in and say, ‘I was told you have everything,’” she says of the store’s customers. “We totally cared about them and took it personally when they needed things and went out of our way to find them.”

But the bread and butter of the business were contractors and construction workers. “I would say our business was 80 percent with contractors and 20 percent retail,” says Patdu, who worked as Clark & Barlow’s comptroller from 1975 until 2012.

Now construction trucks and vans are at the loading dock, and men in sweatshirts and work gloves who don’t want to talk to reporters are hauling away what they can salvage. A group of Amish men from Ontario, Wisconsin, who stand out in their white shirts and brimmed hats, drive away with a load of axe and scythe handles along with miscellaneous hand tools and hardware.

“I know for a fact there’s nothing like [Clark & Barlow] in the city,” Teri Sullivan says. “They’re going to have to go to a Home Depot, where they’re not going to find those things, or online. They’re not going to be able to go in and ask a person who can help.”

“All the contractors are like, ‘Oh my God. Where are we going to go?’” Mucci says.

$10 each

SOLD

Watch Your Step

Sale/Sale/Sale

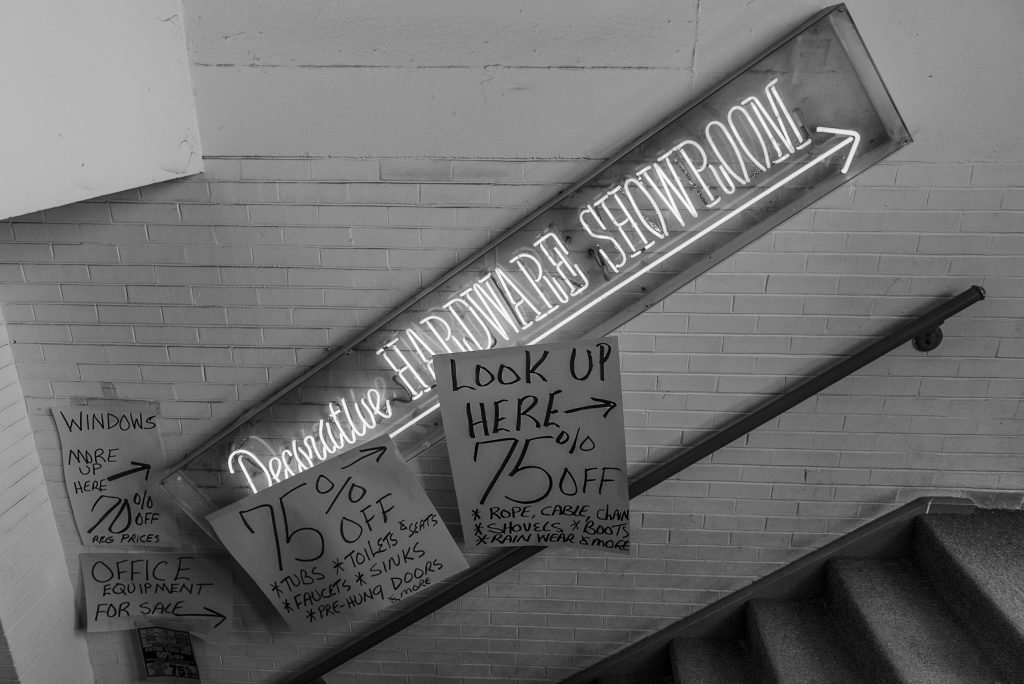

Upstairs, past the hot pink and fluorescent green posters partially obscuring the neon “Decorative Hardware Showroom” sign, the dim lighting and the soft sound of an AM radio station create the atmosphere of a theater set. Track lighting illuminates a room full of boxes, most open and exposing sinks and toilets. A few bathtubs rest near the doorway, and some mirrors lean against the wall. You almost expect Willy Loman to come in and offer to sell you a bidet.

Upstairs, past the hot pink and fluorescent green posters partially obscuring the neon “Decorative Hardware Showroom” sign, the dim lighting and the soft sound of an AM radio station create the atmosphere of a theater set. Track lighting illuminates a room full of boxes, most open and exposing sinks and toilets. A few bathtubs rest near the doorway, and some mirrors lean against the wall. You almost expect Willy Loman to come in and offer to sell you a bidet.

Judy Sullivan, another of Joe Sullivan’s daughters, worked in the showroom for more than two decades. “We had everything, and if we didn’t have it, we would get it,” she recalls. Those were the days before the inventory was in computer databases, when sales were written up on paper and stored away in file cabinets. She left in 2012, about the time that Studio 41, a home design retailer of kitchen and bath fixtures, hardware, and cabinetry, purchased the business.

[blocktext align=”right”]“We had everything,

and if we didn’t have it,

we would get it.”[/blocktext]Across the hall is another room where floor-to-ceiling industrial shelves are crowded with lock sets, hinges, and cylinders. A poster of Miss Makita 2002, Amber Goetz, holding a drill, covers the side of a filing cabinet; a 1992 calendar with a tool-wielding blonde in a pink bikini is taped to a poll. A man in a backpack shuffles shelf to shelf, removes a lock set from its box, leaves both on separate shelves. The wind rattles the steel-frame windows.

The main offices inhabited a room full of beige metal cubicles, now deserted, where phone lists are still tacked above empty phone jacks. A few old IBM terminals remain, along with blank white boards and metal filing cabinets. A sheriff paid for the enormous safe, but hasn’t yet come back to retrieve it. The lady who purchased the coffin carrier also needs to return for it before the building closes for good.

The basement, once off-limits, contains some of the oddest items: railroad car lifters, crane winches, scythe handles. A display board full of casters suggests the full cycle Clark & Barlow has been through over the past half century.

$5 each. Final.

All hinges $5 set

Pulls & Plates $10 each

The caster business is where Joe Sullivan got his start. He and his older brother, Harry, worked for Payson Manufacturing, selling industrial-grade casters. One of Sullivan’s clients was Jack Barlow, co-owner of Clark & Barlow since 1923.

A customer.

“After he worked for Payson for five or six years, he went to Mr. Barlow, who was old, and says, ‘I respect you. I know that someday I want to run my own business. If one of your friends ever wants to get out of whatever business they’re in, I’d be interested in talking to them,’” recalls Joe Sullivan, Jr., his oldest son. “So two years later, Mr. Barlow says, ‘What do you think of this business?’”

According to Joe Sullivan, Jr. and all four of his sisters, what followed was a combination of savvy bargaining and gentlemanly behavior. The accounts differ in some of the particulars, but they agree that Sullivan got wind that someone else was interested and quickly consummated the deal, at which point the two shook hands. Then another offer was made — perhaps by Barlow’s son-in-laws, perhaps by someone else — for more money. But in the end, Joe recalls, “My dad says, ‘You shook my hand.’ And Barlow says, ‘You know, you’re right. I did shake your hand; we’ve got a deal.”

By all accounts, Clark & Barlow thrived under Sullivan’s ownership. It expanded from one to four locations; Sullivan’s family of eight moved from a three-bedroom house to a six-bedroom house. Sullivan was beloved by his employees in part because he didn’t interfere too much with the daily operations of the business. Instead, he was out making connections and sealing deals, as well as pursuing his own eclectic interests, which included playing golf, racing horses, and singing in local bars. “My dad didn’t live to work at all,” Joe Sullivan, Jr. says. “He said, ‘This is great. I don’t want to grow the business any more. I’m very comfortable. So it’s not the American dream of dominating the Chicago area.”

Michelle Diaz, who began at Clark & Barlow in 1991.

But while Sullivan hewed to Barlow’s vision — stocking the shelves with everything anyone could possibly need, prioritizing hands-on customer service over computerization and cost-cutting — things changed around Clark & Barlow. Discount, big-box hardware stores moved into the neighborhood; the internet provided information about and access to hard-to-find items; competition among online retailers led to quick and cheap delivery. Business began to drop off. Clark & Barlow closed the other locations, but even in River North revenue dwindled. At its peak, Joe Sullivan Jr. estimates Clark & Barlow did $10 million in sales. By 2015, it was down to a quarter of that. And meanwhile, costs were skyrocketing. Real estate taxes alone were $80,000. “Clark & Barlow, they’re not here any more because they didn’t change. My dad didn’t change,” he says. “They continued to do business the old-fashioned way, and ultimately that led to their demise.”

After Joe Sullivan, Sr. died, his children looked at the books. Again, accounts differ a bit, but they sold the building and the land to Onni Group for $8.8 million, and the business to Studio 41 for an undisclosed amount that is rumored to have been very low. Joe Sullivan Jr. took care of the handshake on this transaction, but it was far more formal. In exchange for purchasing the business, Studio 41 agreed to offer every Clark & Barlow employee a job and take care of emptying out decades of inventory from the building. “I look at Studio 41 as, they saved us,” Joe Sullivan, Jr. says. “Studio 41 did Clark & Barlow a favor, and Clark & Barlow did Studio 41 a favor because of the name, the history, etc.”

“It was sentimental. It was a little heartbreaking to see it go,” says his sister, Amy Schroeder.

Make an offer

SOLD!

After Studio 41 purchased the business, most of the employees stayed on until the building was emptied. Only Michelle Diaz and two other Clark & Barlow employees accepted the offer to continue on working for Studio 41.

Angela Mucci worked at Clark & Barlow for more than half her life, beginning at the 123 W. Lake St. location.

After that, the great sell-off began. Prices were steadily reduced; spaces were gradually cleared. Eventually the cleaning service was discontinued and the employees had to clean the bathrooms and sweep the floors themselves.

“I think the last day is going to be the hardest because it’s an era that’s ending and who knows what’s really going to happen?” says Diaz.

Most of the long-timers have decided they don’t want to find out. “I think I’m just going to call it a day,” Schelberger says. “That’s enough. It’s hard.”

Mucci, too, chose not to take a job at Studio 41. “I have my good memories, so that’s it,” she says. “When Mr. Sullivan passed away, to me the store passed away.’”

On a dreary March afternoon, this is how it ends, slowly, bit by bit, bolt by bolt, as the wind blows leaves around the dumpster outside.

___

Sharon Bloyd-Peshkin is an associate professor of journalism at Columbia College Chicago. The former editor of Chicago Parent magazine and senior editor of Vegetarian Times magazine, she is now a teacher, a freelance writer and editor, and the advisor to the award-winning student magazine, Echo.

Alec Bloyd-Peshkin is a self-employed carpenter and freelance photographer based in Chicago.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.

Heart wrenching. Are there any wooden signs that might be sent to me in New York? I spent many happy hours/days in a hardware store with my Dad as a kid—and even now. [email protected]

Thanks.

Wow i am so sad, i spent my first 10 years of life playing in all of the clark and Barlow stores. My dad was the General manager there for 26 years. I use to sit on mr barlows lap as a kid.

I remember when joe Sullivan took over the company, i always thought his office was so cool. Especially in that old building on lake st. Most people don’t know but it was the only wood frame to survive the great Chicago fire. Anyway i just had to add a few words of respect to a company that pretty much helped me become who i am.

Thanks to the Sullivan’s for keeping such a treasure of Chicago history for all these many years.

Steve Livingston

A great piece about an amazing place – I cried when I say the sign, locked up and wandered through the aisles teary.

Thank you.

Was this store once named Clark Hall? I thought I used to purchase hardware items for my business in Gary Indiana.(for resale) One of the best stores I ever did business with.