By Alexa C. Kurzius

“Family Run Estate Sale,” reads the modest Craigslist post for a house on Marne Road. Yet when my mother and I arrive at 10:30 a.m., 20 people are already out in front, gathered along the narrow sidewalk. Every 10 minutes or so, a guy with a pad emerges and calls out names. As my we move towards the door, my exposed ankles start to freeze. Like most winter days in Buffalo, it’s damp and gray, and you can watch the slushy snow drip its way into the earth. [blocktext align=”left”]“Did they call your name yet?” she barks. I shake my head no and make a mental note: possible competition. [/blocktext]

I keep my elbows out to avoid the advances of an overly eager plump woman in her mid 50’s wearing a jacket and gloves in mismatching reds. “Did they call your name yet?” she barks. I shake my head no and make a mental note: possible competition. Eventually Pad Guy calls my name. I leave Red at the lawn and walk inside. It’s buzzing with people shuffling throughout the cramped home; their feet tap on the hardwood floors as they move from room to room. I overhear Pad Guy say he grew up here, and I decide he must be the son of the woman who passed away, Mrs. A.

The tidal force of the crowd pushes me into the living room, where I’m greeted by a heavy antique dining room table and some kitchen plates adorned with drab-looking flowers. I pause amid the controlled chaos of 30 people in the small space to notice its dark wood trim. The soft winter light filters through two windows perched above a built-in bookcase. I run into Red in front of a $25 dark wood dresser with a mirror, and she interrogates me about whether I’m going to buy it. A momentary Mexican standoff ensues (I won’t say yes or no and neither will she) before I retreat to the front of the house.

I make my way into a small sunroom, staring at the rectangular dimensions and wondering if Mrs. A lounged here on lazy Sunday afternoons. My fantasy is interrupted by the sight of the COOLEST MIDCENTURY CHAIR EVER, tucked away in the corner. It’s roomy and square, with wide square arms and a deep bottom. The brown upholstery is patterned with swirls and is partially faded, but the arms and legs are taut and timeless. My mom and I lock eyes after we spot the $15 price tag and I dart to the payment table to call dibs on the chair.

******

Marne Road is located in Cheektowaga, a working class neighborhood ten minutes from Buffalo, New York. The mustard yellow home is only a (head) stone’s throw away from Mt. Calvary Cemetery, with scores of acres of tombs that date back to before the Civil War. Many generations of my own ancestors are buried there (I live in New York now, but grew up in Buffalo), including my grandparents. You can even see our family’s surname chiseled on a rectangular gray headstone when you’re driving down Route 33, the east-west highway built in the early 20th century connecting Buffalo to Cheektowaga and its other suburbs.

Before the 33, an electric trolley allowed many of the city’s new immigrants to commute to and from less populated towns and villages. Mainly Germans and Poles settled in Cheektowaga, beginning in the mid-19th century.

Public property records tell me that the house on Marne Road was built in 1925, when Cheektowaga was largely a rural farm town. The owner’s daughter-in-law, Karen, tells me the late Mrs. A’s parents bought the new home right around 1925. This also coincided with the construction of the Buffalo Airport — built in 1926 on top of Cheektowaga’s electric trolley lines — and the opening of the Peace Bridge, which connected the United States and Canada in nearby Niagara Falls in 1927.

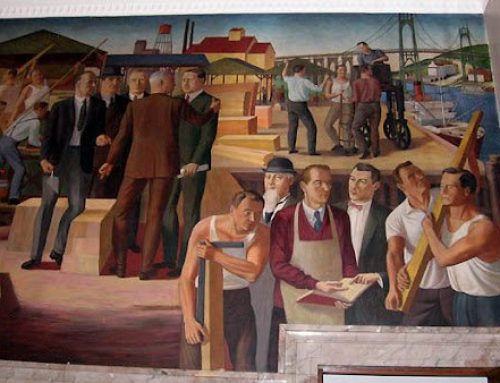

Though Cheektowaga wasn’t necessarily a boomtown in the 1920’s, Buffalo certainly was. Grain, steel, lumber, airplanes, chemicals, and cars were just a few of the industries with a heavy presence in the area. Steel holds a particular importance in my own family, as my great-great-great-granduncle emigrated from Germany in the mid 19th century to begin an iron welding business that later expanded to include steel. [blocktext align=”right”]I think about what Buffalo must have been like when Mrs. A’s parents bought the house: a city with powerhouse industry status that brought an influx of jobs and people to work them. [/blocktext]When my relatives arrived in the city, Buffalo was the reigning grain storage capital of the world, “harboring millions of tons of Midwestern grain in its internationally renowned grain elevators,” according to Mark Goldman in his book about Buffalo, City on the Edge.

Betwixt my battles with Red and search for the unique and antique, I think about what Buffalo must have been like when Mrs. A’s parents bought the house: a city with powerhouse industry status that brought an influx of jobs and people to work them. Mrs. A’s house was built the same year my grandfather was born. The family steel business would not outlive him, just as Buffalo’s economic prominence would not outlast the 20th century.

***

I poke fun at Red but the truth is, I know a good picker when I see one. Darting eyes, jittery conversation, and calculated leaps of faith on items deemed “worth it” — in the emotional sense, fiscal sense, or both. Red and I both passed on the mirrored dresser, and when I returned to the sale in its final hours I saw everyone had as well. I felt validated in my choice; $25 was probably too much to spend on a piece of furniture that couldn’t fit in my New York City apartment anyway.

If I had to go with one rule of thumb for those looking to break into estate sale shopping, it’d be to go with your gut. And be willing to pick through what ostensibly looks like trash. Remember, a little dust or grime shouldn’t take away from the thrill of the find. A few months ago at a flea market, I unearthed a demurely framed image of a bouquet of yellow flowers, iridescently shining on a beautiful black background. You couldn’t tell that at the time though, as a thick, sticky layer of dust coated the whole thing. I avoided thoughts on what the heck happened to this frame to produce such filth. Instead, I had at it with a rag and a mild cleanser, scrubbing the glass until the flowers gleamed and the rag was soiled all the way through. In the end it was worth it.

Sites like Craigslist and EstateSales.net offer photographic sneak peaks of what’s for sale at estate sales, but the truth is, you don’t know what you’ll find until you get there. Thus it helps to be in touch with your tastes. Any midcentury clothing or furniture is right up my alley. And the 1970s–I love the 1970s. I even made an exception to my “no bed linens or lingerie” rule and bought a vintage floral bedsheet that now lives on as a beach blanket. Admiring its flamboyant pink and yellow floral pattern, I sometimes wonder if there was a wild shag carpet and bedroom set to match.

Getting to the sale early is imperative, as the good stuff tends to go the quickest. I arrived at the house on Marne Road a half hour after the sale opened, and had maybe 50 people ahead of me. [blocktext align=”left”]My perspicacious eye tells me the chair is likely from sometime around the 1950s. That was when Buffalo was at the height of its 20th century game. [/blocktext] I know this because Karen told me about her signup list, an attempt to control the influx of enterprising pickers coming promptly at 10 a.m. They probably would have come even earlier, except that Karen stipulated “No Early Birds” in her Craiglist post.

Price is relative. Marne Road’s prices were a steal, though I’ve been to other sales run by estate sale companies that price items more at premium. At one such sale I briefly considered a fine, white Victorian chaise lounge in immaculate condition, but the $200 price tag was far higher than what I was comfortable paying. In the end, the lounge went to a nearby bed and breakfast, which seems more appropriate for the wondrous relic. Besides, it wasn’t really my taste anyway.

My perspicacious eye tells me the chair is likely from sometime around the 1950s. That was when Buffalo was at the height of its 20th century game. Goldman writes that in 1951, the city was the third-largest producer of steel in the country, second-largest railroad center, and produced “enough flour to supply every family in the country with half a loaf of bread every day.”

Buffalo’s passion for production paralleled the rest of the country during the decade. Following World War II, veterans came back to the States with a vengeance, resulting in the rise of innovation, production, and procreation. The 1950’s brought the Space Race, the Baby Boom, and the era of television. This time of prosperity and positive thinking was reflected in furniture design.

Looking for someone to tell me more about the history of my beloved Rust Belt city and the authenticity of my new-old chair, I started with Tim Tielman, director and founder of The Campaign For Greater Buffalo. The nonprofit advocates for the preservation of historic buildings. From Tielman I learned about Cheektowaga’s cable car system, the dozens of industries that have come and gone, and the proud few that are still there. (Like Milk-Bone, which to this day produces 100% of its dog bones in Buffalo! ) [blocktext align=”right”]I don’t have to prod Max too much for him to ebulliently agree on how great estate sales are in Buffalo. Like me, he has noticed the higher volume of used merchandise available at estate sales and flea markets in the Buffalo area compared to New York City. [/blocktext]When our conversation migrated to estate sales, he mentioned how he picked up half of his own furniture from a sale down the street when his family moved into their current house. And then wouldn’t you know it, he told me his son Max is studying the history of decorative arts and design at Parsons The New School of Design in New York and he’d be happy to talk to me more about my chair.

Max corroborated my assumption that the chair is likely from the 1950’s, evident by its shape and decorative elements that evoke the Modernist design style. Characteristics of “Modernism with a capital M” include the idea that “form follows function” and the use of industrial materials in a non-ornamented way, he said.

Modernist style contrasted sharply with earlier design styles like Art Deco of the 1930s and 1940s, which was really about using decorative elements, according to Max. On the contrary, Modernist designers “were completely opposed to that idea,” and tended to create pieces that were “streamlined” and “decluttered” in appearance. He pointed to the social and economic conditions of the 1950s and how “people’s values and interests at that time,” were reflected in the design of the chair.

Max likened the chair’s style to something from The Jetsons. Brown with a boomerang curvature in the seat cushion, it evokes a Modernist style but is “for the everyday sort of person,” he said. The decorative elements such as the raised textured curves you can feel when you rub your hands on the fabric had a “mass market appeal.” The tapered wood legs with brass bottoms reminded him of Danish modern design.

I don’t have to prod Max too much for him to ebulliently agree on how great estate sales are in Buffalo. Like me, he has noticed the higher volume of used merchandise available at estate sales and flea markets in the Buffalo area compared to New York City. Many original midcentury furniture designs are still manufactured and sold new in home décor stores at price points that far surpass my own budget. On the other hand at an estate sale, “you’re able to find pieces that were probably original and in the time period you’re looking for. They’re not reproductions,” he says.

I’m glad Max mentions the history you inherit when you find an item at an estate sale, as I wholeheartedly share his sentiment. “There is a thrill in hunting down treasures in places like that,” he says. “There’s a sense of history that comes with it.” My chair’s prosperous past is partly what inspired my purchasing decision (and the $15 price tag makes it a no brainer). Buying the chair gets me its life story for free, and insight into a past I’ve always been curious about.

I asked Karen about her about her mother-in-law’s personal style. “Whatever’s cheap,” she told me over the phone, emphasizing that she didn’t often have the money to buy new things. [blocktext align=”left”]Karen mentions offhandedly that at one point there was a couch to match my brown chair, and I die a little inside at the thought of the discarded couch sitting at the curb, sad and forlorn[/blocktext]I marveled at her taste and what must have gone into Mrs. A’s purchasing decisions, given that a lot of other furniture in the house was leftover from her parents, who lived in the house before her. The chair feels positively futuristic next to the Victorian dining room set, heirloom furniture bequeathed to Mrs. A. Karen mentions offhandedly that at one point there was a couch to match my brown chair, and I die a little inside at the thought of the discarded couch sitting at the curb, sad and forlorn.

*****

It’s snowing lightly outside when I attend an estate sale in Amherst, an affluent suburb by Buffalo standards, and where I grew up. I’m here to speak to Sandra D. Zeimer, the first person to start an estate sale business in Buffalo. Sandra brought the concept to the city in 1978, founding her company that appraises household items and operates sales for interested families. Primarily, these sales happen after death, but Sandra also does work for people who are downsizing their homes, or for those who are going through divorces.

Her expertise in antiques began with her grandmother, and provided enough of a knowledge base to appraise the items and run the sales. Since then, the thousands of sales she’s run over the years has helped her to know what sells and what doesn’t.

On the day I speak to her in Amherst, Sandra wears a light pink turtleneck beneath a black cardigan. Her face is rouged. She smiles a lot. She interrupts our conversation frequently to say hello to a number of regular customers who pass through the carpeted dining room where we sit. They’re looking for finds just like me, and she calls them her friends.

“It’s hard work,” Sandra tells me, when I share my pipe dream to run a business just like hers. “You can work until you die” in this business, she says. (The irony of her statement isn’t lost on me here.)

Jewelry, sterling silver, and nice paintings — these are always in demand. Furniture demand depends on the trends, though Sandra tells me Midcentury furniture design is desirable, and I beam a little inside.

Our conversation is interrupted by a burly construction worker who enters the house in his work boots. He tells Sandra the sale traffic is becoming a hazard, and his team needs to block the road to do their job. But this stymies the influx of customers, she says, and is not good for business. They argue for a few minutes and then he disappears briefly upstairs, only to return with a JFK Memorial Album record in hand (the same record I was eying myself but a few minutes prior). His eyes twinkle and he holds up the record proudly before retreating back to the street.

Sandra mentions an upcoming sale she’s running at a waterfront mansion in Lewiston, (a scenic, stately town near Niagara Falls), and another sale at the home of a QVC-obsessed shoe and jewelry shopper in Kenmore (a middle-class town with many two-family homes). But overall, the estate sale business has declined over the years. The internet is partly to blame, since appraisals can now be easily done online.

Part of managing a successful estate sale business today is maintaining an up-to-date website, so each week Sandra’s son George uploads a phalanx of photos showcasing available items at each upcoming sale. Sandra estimates that the website accounts for 75 percent of their customers. It “lets them know whether it’s worth their time to come,” she says.

George is Sandra’s partner and heir to the family business, having started it with his mother 35 years ago. He’s been working to modernize the company since moving back to Buffalo after a 17-year stint as an accountant in California. I catch up with him at another estate sale in Amherst, where he’s finishing up the day. [blocktext align=”left”]Twenty years ago, “a big house in Buffalo full of antiques” could gross $30,000 or $40,000 “in one or two days,” says George. Now the Zeimer family does two or three sales a week just to make the same amount. [/blocktext]He shares with me his industry secret, a website that aggregates eBay sales for the week. As I eye the price of a 1940s turquoise China set I’m interested in buying, he shows me a similarly priced China set sold on eBay a few days prior. The eBay evidence makes me reticent to bargain, but I do it anyway and he throws in a $40 gravy boat for free.

Twenty years ago, “a big house in Buffalo full of antiques” could gross $30,000 or $40,000 “in one or two days,” says George. Now the Zeimer family does two or three sales a week just to make the same amount. “The only thing we don’t sell is food, liquor, and undergarments,” he says.

Estate sales are a sign of Buffalo’s prosperous past, but the decline of high-quality inventory over the years seems to echo the city’s late 20th century industrial exodus. The grain industry was more or less destroyed with the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway, which opened in 1959 and directly connected the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, thus eliminating the previous necessary stopover in Buffalo. Also, local ownership of grain companies was superseded by national companies: “Cargill, International Milling, Standard Mills and Pillsbury,” says Goldman in his book, “had little commitment to the local economy.”

Other industries soon followed. Bethlehem Steel — a plant that employed nearly 8,000 people and had been in operation since 1906 when it was built by Lackawanna Steel — shut down in 1983. Goldman writes that the company’s president “could not justify the capital expenditures to modernize” the plant, an issue that was partly aggravated by high local taxes and an “’unfavorable location.’” Bethlehem was instead committed to its newer plants in Indiana and Maryland. Ironically, the plant that once made 10,000 tons of steel per day was demolished beginning in 1984. [blocktext align=”right”]I’m not just a hunter, I’m a historian, incorporating bits and pieces of others lives into my own. Buffalo’s industrious past lives on in my living room, re-envisioned and reupholstered. [/blocktext]My grandfather’s smaller, Cheektowaga steel business was also shuttered in the 1980’s, as the company couldn’t sustain the growing operation costs and competition from national and international steel companies.

I ask Tim Tielman if he had heard of my grandfather’s plant, and he said he hadn’t. I mention the black heavy-windowed edifice with multiple short smoke stacks that was torn down and replaced by a Target. Everyone knows the Target; it’s across from the Galleria Mall, one of the area’s finest displays of urban sprawl erected in 1988.

While many might view my hobby as quirky, eccentric, or just plain weird, I look at estate sale shopping as another way to get to know my city’s past. I’m not just a hunter, I’m a historian, incorporating bits and pieces of others lives into my own. Buffalo’s industrious past lives on in my living room, re-envisioned and reupholstered. My chair, for as much as I love it, could use a gut renovation. Mrs. A was a smoker, which you can still detect faintly even after sitting in my mother’s garage for a few months. At one point a cat certainly clawed at the chair’s arms, and seat cushion is just about at the point where the springs accost your bottom when you sit on it. But that’s nothing a good furniture rehabilitator can’t fix.

I’m not the only enterprising junklugger who has an interest in nabbing that historic authenticity when it’s available. “Every single thing in my house was somebody else’s,” says Mary, Sheila Zeimer’s employee since 1998. The petite, retired hairdresser sports perfectly shellacked silver waves and speaks in excited rapid fire. “I came and came and came and made friends with the girls,” which eventually led Zeimer to recruit her when she learned of her retirement from hair. “I’m taking the money now instead of giving the money out,” she says of her hobby-turned-job.

“I love it, I love it, I love it,” she repeats as she tells me how she started going to auctions and estate sales at age 20 and hasn’t stopped. “This is not stuff, this is gorgeous furniture,” she says as she points to the provincial bedroom set at the Zeimer sale in Amherst.

What I hope is for Buffalo to regain some of its vibrancy that was so prevalent so many years ago. Restoring its industrious powerhouse position may not be possible, but in some ways, the city is already developing its own proud, residential niche. For example, Bernice Radle and Jason Wilson run Buffalove Development, an organization of microdevelopers that buy decaying city properties and rehab them for eventual rentals or sales. Their business recently received national attention, after being profiled in the New York Times.

Few cities can boast such a rich history, and more importantly, such a solid set of citizens who fervently revere the glory days. Tim Tielman passed his love of the city onto his son Max; Sandra is passing her knowledge of antiques onto George; and I still speak to my uncle, and old steel company employee, about the family business. Maintaining this reverence for the past is nearly as important planning for the future, and I’m confident Buffalonians will continue to bestow these values onto their offspring. But in the meantime you can find me at an estate sale, digging through another man’s treasure.

Alexa C. Kurzius is a Buffalo-bred writer living in New York City.

Buffalo exports a lot of beautiful old stuff to the rest of the country. Nice for it to be seen and appreciated elsewhere, but kinda sad, too.