This essay is an excerpt from The Cleveland Neighborhood Guidebook (Belt Publishing, 2016). Order your copy here.

By Brad Masi

I. GHOST STREAMS

Late May, the cusp of summer, I glide down the brushy side streets of Cleveland Heights. My bicycle jiggles over the occasional stretch of brick road, reminding me that pavement was originally invented to make biking easier.

I’m biking to Coventry Village, the Bohemian epicenter of Cleveland Heights, a swirling mixture of antiques, vintage toys, head shops, churches, grocers, hardware stores, funky imports, indie rock bands, revolutionary and countercultural books, cafes, acting schools, sports bars and culinary options that stretch from middle America to East Asia. They even have a place where you can get locked in a room and forced to solve complex riddles to escape.

A haven for the easily distracted, Coventry often lures me in with a simple mission in mind, perhaps a jaunt to Heights Hardware to fetch a screw for an ailing cabinet back home. An hour later, I find myself clutching a handful of Star Wars figures from Big Fun while wolfing down a bowl of French onion soup at Tommy’s, hoping to make a poetry reading at Mac’s Backs that I just found out about. At some point, it occurs to me that I never made it to the hardware store for that damn screw.

But today, I am in pursuit of a different kind of meandering adventure in Coventry — a hike along Dugway Brook, which runs right through the center of Coventry Village. On the surface, this sounds like a particularly challenging, if not delusional, quest, as there is no actual water visible.

Like many urban streams in Cleveland, Dugway brook is mostly underground, with the exception of this brief stretch where it runs its historical open course down a gorge in Lakeview Cemetery.

Roy Larick, a local anthropologist, leads the search for this “ghost stream,” his description of a historic stream that has disappeared underground, locked away in concrete culverts beneath the hapless footfalls of the denizens above.

Roy leads our motley band of natural historians, bird watchers, history buffs, and extreme hikers like a docent through the Land of the Lost. The contemporary facade of Coventry fades as our group shuffles through the bustling stream of shoppers and casual strollers. With an urgent gait, Roy makes a beeline to the least spectacular landmark in Coventry, a three-story parking garage that gobbled up a lot of good urban space to make the district accessible to our heavily motorized public.

Roy arrives at a densely wooded area along a ridge behind the parking garage, pointing to a sandstone outcropping that rises amid a mix of dirt, ivy and urban detritus: plastic bags, discarded condoms, snack bags and other washed-up souvenirs of our disposable culture.

The stone formations rise like the scepters of the vast inland sea that covered the Cleveland Metropolitan area 350 million years ago. At that time, the land that would become Cleveland resided around the latitude of Peru, part of Pangaea, the contiguous land mass that preceded continental drift. I imagine the Appalachian Mountains towering on the horizon, slowly eroding into this sea. Wave action piled sand from these mountains into beaches and shallow shores. Compressed over geological time, these beaches became the sandstone formations in front of us, the lost guardians of Pangaea, relegated to their post behind Coventry Garage.

Coventry Village sits in a geologically dynamic space, a terrace that perches about 300 feet above the flat Lake Plains that define much of Cleveland. Underlying this terrace is a bedrock layer unique to Northeast Ohio: bluestone. It is encountered perhaps most frequently in the side walks that make Cleveland Heights so walkable. Roy runs Bluestone Heights, an educational organization whose name comes from this bedrock edifice upon which many of the inner-ring suburbs perch. Roy looks at the Heights not as a tangle of zip codes and municipalities but as an integrated complex of communities united by a shared geological legacy and a series of parallel streams that each form their own exclusive small watershed that drains into Lake Erie.

For Coventry, this stream is Dugway, whose patient erosion over the 14,000 years since the glaciers receded revealed these sandstone formations and shaped the land on which Coventry sits. Roy takes us from the parking garage, promising to give us a glimpse of this elusive stream.

We arrive at the intersection of Coventry and Lancashire Roads, where Roy stops at a sewer grating. A trio of Jehovah’s Witnesses stand beside the grating with a table weighed down with flyers promising salvation. Roy describes the route of the stream right where we are standing, tracing Chasing the Ghosts of Coventry Village remnants in the landscape around us. As he speaks, the undulations of the stream’s ancestral banks become suddenly noticeable in the terrain of parking lots, sidewalks, and yards.

I find myself strangely saddened by the disappearance of this once-great waterway. Pedestrians shuffle by, dodging the Jehovah’s Witnesses and our strange band of ghost stream chasers, oblivious to the ancient legacy that lies underfoot. I long for a glimpse of what once used to be here.

Just then, Jim Miller, a local stream specialist also on the tour, produces a four-foot length of PVC pipe and places it at the top of the sewer grating. We take turns cupping our ears to the top of the pipe, the sound of the rushing stream below suddenly amplified over the traffic, crowds, and urgent proselitizing.

The sound of the stream connects me to a more ancient spirit of Coventry. At that moment, I understand what Roy referred to as “deep history,” a recognition that Cleveland is not a recent construct, but rather the culmination of an ancient natural legacy woven together with more recent urban settlement. Understanding this legacy connects us to a dynamic world bigger than ourselves that calls for our responsible stewardship.

Situated in the center of Lakeview Cemetery, this concrete flood-control dam could probably best be described as architecture inspired by Joseph Stalin.

A few hundred feet from where we stand, Dugway Brook opens up and tumbles down a gorge of grey-hewn bluestone in Lakeview Cemetery. It is a fleeting moment where the stream recovers its untrammeled natural glory before being channeled into a concrete flood control dam, a monument of Soviet-style brutalism that sits strangely in the center of the cemetery.

Down from the Dugway gorge, tombstones perch delicately upon the steep descent of the Portage Escarpment, the terminus of the bedrock formation that gives the Heights its stature before the descent into the Lake Plain of Cleveland. A scan of the tombstones here provides a jumbled account of Cleveland history, one that includes Civil War generals, U.S. Presidents, 22 Cleveland mayors, and one comic book anti-hero from Coventry who’s raspy voice can almost be heard reading his epitaph: “Life is about women, gigs, and bein’ creative.” Like Dugway brook, comics writer Harvey Pekar has shaped the contours of the rich literary landscape around Coventry.

II. GHOST WRITERS

In the same way that Dugway was forced to the oblivion of its underground channel, Cleveland’s literary scene has similarly faced a history of suppression. And like Dugway Brook, finding that moment for its true, natural expression in the bluestone gorge of Lakeview Cemetery, Coventry serves as a node for the free flow of ideas and expression in Cleveland.

Many writers, poets, artists, publishers, and graphic novelists find their home here and many more were hatched here before their winged migration to other territories. The legacy of two pioneers of literary expression and free speech can be found here and, like good ghosts, remain at the edges where you have to look a bit to find them. To see them, and understand the urban history of Cleveland that each embodied in their work, it is best to be on foot.

Many writers, poets, artists, publishers, and graphic novelists find their home here and many more were hatched here before their winged migration to other territories. The legacy of two pioneers of literary expression and free speech can be found here and, like good ghosts, remain at the edges where you have to look a bit to find them. To see them, and understand the urban history of Cleveland that each embodied in their work, it is best to be on foot.

On a beautiful July morning, I tramped down the backstreets of Coventry, worried about missing the opening dedication of Pekar Park, a monument to Harvey Pekar’s work. Aided by the steep decline of the Portage Escarpment, I hustled down the brick-covered Mornington Lane as it flowed into Euclid Heights Boulevard. As I often do, I skipped halfway across the street, then made my way along the grassy, tree-lined median to Coventry.

The median fills me with a strange nostalgia for a part of Cleveland that I never experienced. What seems an aesthetic flourish to dampen traffic, these medians once served as the corridors for an extensive electric streetcar network that connected neighborhoods throughout Cleveland. These medians occur throughout Cleveland Heights, a streetcar suburb, which hit its initial growth period in the 1920s, a time when private automobiles were mostly the province of wealthier classes. Then, people walked, biked or took streetcars. Cleveland Heights still retains the basic bones of a walkable and transit-oriented urban environment as a result.

As I approach Coventry Boulevard, I cross over the remaining half of the boulevard and stride toward a small gathering of people circulating among canopies and a makeshift stage on an open peninsula of land in front of the Grog Shop, a haven for indie bands. I pause to admire the marvel of the curved architecture looming above the crowd as apartments along the Boulevard seamlessly flow into Coventry’s retail district. This arc of buildings serves as a ghost relic of the streetcar line as it curved north onto Coventry Road. As a fixed rail system, streetcars could not make sharp turns. Instead, they made wide arcs to gradually shift direction, a common urban design pattern encountered in Cleveland Heights.

With the streetcars gone, this bonus piece of open land has, since the 1960s, served as a neighborhood gathering and performance space, as Coventry shifted from a predominantly Jewish neighborhood to the center of Cleveland’s counterculture scene. But, recently, this space had been busted up by the installation of concrete planters and barricades installed to discourage community assembly. The loss of this space particularly struck Harevy Pekar’s wife Joyce Brabner, who recalled that the spot used to be a “haven for nonconformist and creative youth until overblown anxiety about flash mobs and kids hanging around without money to support local business led to curfews and what many felt was repressive redesign.” Through the park, Joyce saw an opportunity to return the area to “its earlier, youth- and arts-friendly state by removing the big blocky ‘people bumper’ planters that were installed to discourage assembly, and welcome back young people, street musicians, storytellers, chess players and others to a communal meeting and gathering space.”

But the space has a much deeper personal connection for Joyce and many others who recall the space as a nexus for the kind of communal artistic expression that propelled her husband’s work. At the opening ceremony, Joyce described how “Harvey really loved moving into Coventry because that’s the place where he felt like he was a writer, he was creative, and the kinds of things that he was about were appreciated.”

More than a decorative element, the tree-lined median along Euclid-Heights Boulevard once flowed with electric streetcars that connected neighborhoods throughout the city.

Joyce describes how “Harvey used to walk down from his apartment on Hampshire to this corner where everyone would hang out and he would stand there and tell stories like a stand-up comedy routine.” She also pointed out his likely ulterior motive of “impressing girls.” Nestled among the trees, a series of banners line the park as an ambulatory comic strip, each capturing a scene of Harvey’s life in Cleveland.

The dedication of the park brought in an assembly of people a variety of ages who recalled their interactions with Harvey. Steve Presser, owner of Big Fun, recalled watching Harvey constantly going in and out of his apartment, often clutching piles of albums, used books, or gesticulating wildly as he talked to himself. Joyce later pointed out that this was how Harvey would sometimes reenact dialogue for his stories.

As I listened to people’s recollections, my attention drifted to the stately marquee for the Centrum Theater just beyond the park. Now a church, the theater previously went by the name of the “Heights Art Theater,” a common location featured in many of Harvey’s comics. In 1959, police raided the theater and arrested its manager for screening the French film The Lovers, which the county prosecutor deemed obscene. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, which upheld the rights for the film to be screened, putting Cleveland at the epicenter of national efforts to protect free expression from the country’s more puritanical urges.

Ten years later, Cleveland poet d.a. levy was arrested for distributing poetry deemed obscene by the same county prosecutor. The prosecution of levy drew Allen Ginsberg, who himself survived court efforts to censor “Howl,” to Cleveland to defend levy’s right to free expression amid an unusually rigorous suppression. Ginsberg recalled the harsh treatment of Cleveland police who began to make a habit of raiding coffee houses to bust up poetry readings: “They even came into a coffee shop on Euclid Avenue while I was here and lined us all against the wall at gunpoint,” Ginsberg recalled.

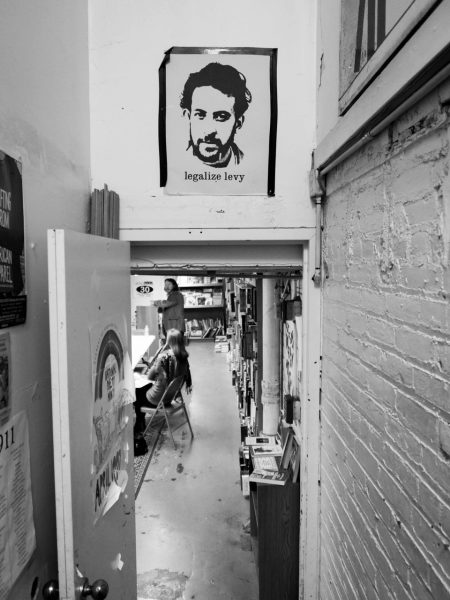

Today, the spirit of levy inhabits Mac’s Backs bookstore. Above the basement stairs, his angular vestige stares down from a poster reading “Legalize Levy,” a reference to the late 1960s campaign against efforts to suppress free speech from the highest levels of county government. The bookstore’s owner, Suzanne DeGaetano, was introduced to levy by poet Daniel Thompson, another Cleveland legend who once resided in Coventry. Thompson began organizing poetry readings at Mac’s, including readings of some of levy’s work. Inspired by levy and motivated to celebrate his legacy on the 20th anniversary of his death, she organized a gathering in 1988 to celebrate his work. The event also captured the spirit of independent publishing that he pioneered through his “mimeograph revolution,” a reference to the machines that opened up whole new worlds for underground publishing. A number of subsequent “levy fests” have continued the legacy of levy’s poetic inspiration over the years.

At Mac’s Backs bookstore, the angular vestige of d.a. levy stares down at patrons as they make their way to the basement where poetry readings and workshops often take place.

A decade after levy’s struggles with Cleveland law, a similar spirit for self-publishing motivated Harvey Pekar to cash in his record collecting habit to finance the publication of his first 16 years of American Splendor.

Coventry, especially in the early years, provided a consistent back drop for Harvey’s life and interactions with people on the streets. Like levy before him, Pekar became a literary pioneer, one of the first to define the autobiographical comic.

Levy and Pekar both produced unique archives of street-level observations of Cleveland, one transcendental and the other existential. It is worth noting the importance that walking played in both writers’ lives, offering a pace for the slow observations and accidental encounters that make the life of good stories or poems. Too poor to afford a car, levy wrote “Cleveland Undercovers” as a succession of stops along a rapid line. He wrote at a time when freeways and urban renewal projects were carving up neighborhoods and obliterating much of the unique history of an immigrant city. The book Mimeograph Revolution recalls how levy “loved the life of the streets and may have wanted to stay close to it in cities,” a sentiment similarly conveyed by Harvey Pekar, whose issues of American Splendor each begin with “From off the streets of Cleveland…”

As I walked home at night after a screening of the documentary American Splendor, perhaps one of the best archives of Cleveland history that I’ve seen, I paused at a sewer grating to listen to Dugway bubbling its quiet way below and a verse from Levy’s “Cleveland Uncovers” popped into my mind:

Sometimes city

When I walk at night

I slip into your past or future

___

Brad Masi likes to walk, bike or hike up and down the Portage Escarpment in Cleveland Heights, as it gives a momentary illusion that he’s still in Colorado where he grew up. When not wandering around aimlessly, Brad makes films, writes, and consults on sustainable community development.

References: Interview with Joyce Brabner appearing on 90.3 Sound of Applause July 23, 2015.

d.a. levy and the Mimeograph Revolution, edited by Larry Smith and Ingrid Swanberg, Bottom Dog Press in Huron, Ohio. 2007.

This is an excerpt; order the complete Cleveland Neighborhood Guidebook here.

Belt is a reader-supported publication — become a member, renew your membership, or purchase a book from our store.

Thank you for this Brad. Very important for us to tie together the natural world beneath our feet and make some sense of where we were as a community just a short time ago. Have there been any attempts to expose a little bit more the brook? I have to agree that one reason I don’t go to the park space near the grog shop is the bunker like feeling of the concrete.Thank you again for the echo of the shape of things from the past!