By Jonathan Welle

Why has Cleveland failed to solve the slow-motion crisis of lead poisoning, which dims the future for thousands of children and families each year, even when other cities have done so long ago?

Cleveland’s failure to eradicate lead poisoning is systemic, says Kim Foreman, Executive Director of Environmental Health Watch (EHW), a public health non-profit organization in Cleveland. Old, poorly maintained homes and other environmental factors expose children to lead. But the problem persists because efforts by government and community groups are fragmented, and too often overlook the experience of the people affected by lead poisoning, says Foreman.

Foreman has fought to stop Cleveland’s lead crisis since she joined EHW in 1999 as a part of Americorps. At the time, she was studying sociology at Case Western and raising her two young children; addressing lead poisoning in Cleveland, she’s quick to admit, was not her top priority. She took a temporary position at EHW because ‘it seemed like a good way to make some money and go to school,’ she says.

Foreman turned her job into a long career working to halt lead poisoning and other public health challenges in Cleveland.

Under Foreman’s leadership, EHW works on public health from the perspective of environmental health, which considers how where we live affects our health. Almost two decades after she took a college job with EHW, Foreman has become a leading expert on Cleveland’s lead poisoning crisis and the city’s response to it.

Foreman implies lead poisoning is not a health problem – it’s a political problem. To eliminate lead poisoning and other environmental health challenges, Foreman says, Cleveland needs a different approach.

____________________

BELT: You said when you first started working for EHW you had ‘no interest whatsoever’ in environmental health. But 17 years later, you’re the Executive Director of the organization and a leading advocate for lead abatement and environmental health in Cleveland. When did you get passionate about addressing environmental health inequities?

Kim Foreman: I started learning about the effect of impact of lead on families and communities [in the 1990s, when] I was tutoring a young child who was going to the first grade in St. Clair Superior.

At that time, over 1 in 3 children in that neighborhood had confirmed levels of 10 [micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood, the level of lead poisoning the Center for Disease Control and Prevention considered a ‘level of concern’ before 2012. In 2012, the CDC lowered the threshold to 5 micrograms per deciliter, though the CDC states that there is ‘no safe blood level’ for lead exposure.]

Kim Foreman

She was having such a hard time remembering week to week her alphabet, and I couldn’t understand why she couldn’t retain the information. I just got so involved with this young child. I called her mother. I was even working with her on the weekends. Her teacher was like, ‘She disrupts the class,’ and this and that.

The light bulb just came on. I was like “This child could be lead poisoned.” I started thinking, “Well what about all the kids in this particular classroom? What about all the kinds in the city of Cleveland school system? What about all the children connected to lead who might be in the juvenile system?”

Then I started to tie [social] ills in the families to the issue of lead.

I was going in houses, with mothers, like me, who were single parents, just like me, who were moving from house to house. Every time I went to a house, it felt like it was me. I could see myself.

The families didn’t understand the issues [related to lead poisoning], and the impact it could make on their children, and the long-term effects. It was sometimes generational. The grandmother would say, ‘Oh yeah, my child has lead poisoning.’ Then the mother of the child in the home would say ‘Yeah, this child has lead poisoning or is displaying certain behaviors.’

It seemed like there was a disconnect between the information, the impact, and the resources.

BELT: How does EHW approach lead poisoning and other problems of environmental health?

Foreman: We look at the house as a system. We try to make sure we’re not thinking in a silo fashion.

[If you approach the problem in silos,] you go out to the house for lead, then you might [take a separate trip to go] out to the house for asthma. Versus looking holistically and addressing all the health hazards. By looking at housing [holistically], we address the whole system.

Yes, we have to test kids. Yes, we have to educate parents. Yes, we have to do programs. But, systematically, how are we addressing the [environmental dangers present in the] housing stock?

BELT: You visit a lot of people affected by lead poisoning in their homes. What have you learned from those visits?

Foreman: What I learned was following up with folks was like 90 percent of what I should be doing.

A lot of time people are left hanging. They don’t know who to call, or they call and people don’t call them back. I started to feel like I was that connector between people getting access to resources, learning information, or being left behind or falling through the cracks.

I ran into one young lady in Cleveland Heights on Section 8. Her child had lead poisoning. She said ‘I think my landlord is paying the housing inspector and CMHA [lead] inspector off.’

If she’s getting an inspection every year through CMHA, and they were checking for lead at the time, it seemed weird to me that her child would have lead poisoning.

At that time I had a relationship with the Head of Inspections for CMHA . I called her and I said, ‘Something’s going on. This lady feels like no one understands her situation.’

Immediately there was a special investigation of her home. I think that [the original inspector got fired].

That woman called the Plain Dealer –she called everybody. She acted based on getting the right information, activating her to advocate for herself.

I was empowered by seeing that EHW created a space for her to tell her story, advocate for herself, and actually someone just listening to her, making the call, and they responded.

That project was really about merging policy with activism and grassroots organizing. It was powerful. And I started to understand.

Now I notice that if I make the call, people get answered. I don’t feel like it should take that. But I understand that I have some responsibility in helping get things done in that way.

BELT: How do you explain this disconnect between the resources to solve lead poisoning and other environmental health challenges and the people living with the effects of those challenges? What’s keeping those things disconnected?

Foreman: I don’t know if we’re organized enough in this city, where you have a collective voice speaking to power.

I want people to be able to organize and advocate for themselves.

There’s a lot of organizations speaking for people, and on behalf of people. I don’t think there’s anything really wrong with that. But what [EHW is] doing is getting to the table, trying to push the envelope, trying to put that perspective [of people affected by lead poisoning] on the table.

Residents – they get it, because they’re experiencing it. Decision makers – sometimes they don’t they don’t get it. They’re siloed. They’re single-issued focused.

We’ve got to stop blaming the parents, saying they just need to be educated. There’s a lot of people that are educated. Are we listening to what they’re saying? If it’s not the language we’re used to, are we turning a blind eye to what people are really telling us because they’re not speaking in a particular language?

The question is, who’s leading? A lot of times, [community groups] want to work in a particular neighborhood, but there’s nobody working with them from the neighborhood, or anybody that can understand that perspective on the leadership team.

BELT: How can public health groups in Cleveland, and the people who work for them, change how they approach lead abatement to improve outcomes?

Foreman: Just because people [who work for community groups] can say intersectionality, doesn’t mean they know how to implement it.

We could talk about the folks in the impacted communities,. But are we willing to go and listen to what they have to say? Are we willing to go to their neighborhood, and sit down, listen, then act according to what their issues are?

I’m not sure that’s happening. Okay, I have a community meeting, and everybody talks, and I say “Okay, check.” Versus really being authentic about hearing, and partnering, and building relationships with people.

It takes more than driving down to Kinsman one day. It takes relationship-building and trust. That takes time and work. I understand that. But you’ve got to have the spirit and humbleness to be willing to do that. And it isn’t about a paycheck.

It could come down to having a community meeting, versus having a real authentic relationship.

These are people with families that are dealing with major issues day to day. We have to try to meet people where they’re at, both physically and mentally

I have more time now that my children are grown, but we all need balance in our lives–this is hard work.

You can’t just have the same people swooping down into the community from the suburbs. We need to first look look for leadership and talent within the community. Who’s leading? Who’s getting the resources?

BELT: What assets does Cleveland have that it can use to make progress on stopping the lead poisoning crisis?

Foreman: We have a lot of leaders here that have been working on healthy homes.

EHW and partners pioneered the healthy homes movement back in the 1980s.

We as a community [EHW and other advocacy groups] have reduced our rates greatly and have influenced the CDC to reduce the [elevated blood level action level from 10 to 5 micrograms per deciliter].

We have a lot of smart people here. I feel that we as a city should be working together on the solution. I feel that the city folks, the departments, the leadership, the data folks, and the residents that are affected, and could work on systematic change together.

Sometimes people are so quick to say what we don’t have. Sometime it’s the way we utilize the resources we have, and the way we do our work, that needs to be changed. We have money and resources. It’s what we decide to do with them.

I was in a meeting about infant mortality way back. There were about 20 programs around home visits services for babies. I said, ‘Well, before, you say we need another program, look at all the programs we have, none of which work. We have the worst infant mortality rate in the country.’

The problem is the money that you’re taking is not working. So how do we use the resources we have to do the work differently.

BELT: What’s EHW working on now to address the lead poisoning crisis?

Foreman: Through our new program, BuildHealth Challenge, we’re building an integrated data system with the City Administration, which EHW has committed resources to help implement.

I’m pushing the idea of working on solutions together as a collective community. I don’t think the silo approach works for any complicated issue.

We want to make the voluntary lead maintenance certificate mandatory, along with enforcement of the City’s existing rental registry. Right now there’s no proactive inspection process.

EHW understands low-cost remediation strategies that would protect the children, keep the home safe for families, and is not going to cost the landlord $10,000.

With that integrated data system [and the mandatory certificate program], our expectation is that there will be a portal for the residents to look for designated healthy homes zones. This would create a market for healthy homes. Residents would be able to look for houses that have been inspected for lead. They can go into the system and say, ‘Okay, I can choose better now because I’m more informed about what the status is.’

We’re focusing our BuildHealth pilot in Clark-Fulton. We have resources to inspect homes, to advocate for enforcing the rental registry. The goal is to create healthy homes zones in a targeted area based on data we collected. We have money to work on asthma intervention through MetroHealth hospital. We are going to see how a prevention model pilot can work. There’s a similar effort in Glenville, funded by the Cleveland Foundation.

Jonathan Welle is an occasional writer in Cleveland.

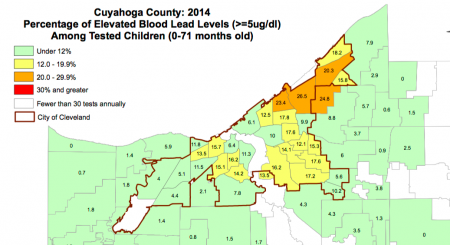

Cuyahoga County map courtesy of Cuyahoga County Board of Health

Interesting story. I had no idea how bad the lead poisoning problem was in Cleveland. Does the residents know that the water has lead in it? If yes, do they still use it for drinking and cooking? If yes, I suggest the water company hand out flyers for every resident informing them that they should not use the water for drinking and cooking and how bad lead is. Maybe they do not know the effects of lead in the water. They need to buy water bottles.

Thanks for the article, but Toledo leads the way. http://www.cleveland.com/opinion/index.ssf/2016/08/toledos_lead_safe_ordinance_sh.html