by Elizabeth Catte

Photography by Queer Appalachia

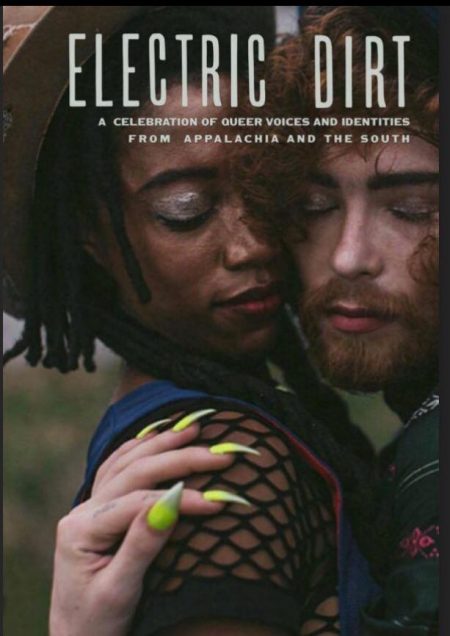

Granny witch. Dirt femme. Two-spirit. Farm-Her. Affrilachian. Fag Hillbilly. The individuals in the radical community formed through the Queer Appalachia network claim many identities and many geographies defined by their own truth and images. Their lush 200-page visual record of queer rural life — Electric Dirt: A Celebration of Voices and Identities from Appalachia and the South — is out now, self-created, self-funded, self-published, and above all, transcendent. And with their crowd-funding goal shattered four times over and a social media reach of over 60,000 people a day, Queer Appalachia might be the most dynamic and diverse Appalachian media organization you’ve never heard of.

Queer Appalachia is a collective of artists and creators dedicated to claiming their own labels.

Queer Appalachia is a collective of artists and creators — contributors to Electric Dirt include author Carter Sickles, photographer Akrum Salem, artist Shellyne Rodriguez, astrologist Chani Nicholas, and many more — dedicated to claiming their own labels. Project organizer Mamone, an audio engineer and producer, first envisioned Electric Dirt as a zine, a tribute to artists and activists Bryn Kelly and Amanda Harris, who both died in 2016. Mamone started a fundraising page in January 2017 with a modest goal — around $8,000 for an ethically-printed first run — and set a target of 100 pages of art and text. “When we first started fundraising,” Mamone said, “we had no idea of the kind of zine we would be making … I thought it would be made with a glue-stick and a Kinko’s card.”

It’s been a transformative year for Queer Appalachia. The collective sailed past its initial fundraising goal to secure over $30,000 in donations to bring Electric Dirt to life, which became a full-fledged book in the process, and fulfilled another $20,000 in direct sales after the book’s release in late-December 2017. On the way, Queer Appalachia established a micro-grant program to help fund queer and/or trans black, indigenous, and people of color-led (QTBIPoC) creative projects. There’s even a special partnership between Queer Appalachia and the Foxfire Foundation, an organization dedicated to the preservation of Appalachian traditions, in the works.

It’s been a transformative year for Queer Appalachia. The collective sailed past its initial fundraising goal to secure over $30,000 in donations to bring Electric Dirt to life, which became a full-fledged book in the process, and fulfilled another $20,000 in direct sales after the book’s release in late-December 2017. On the way, Queer Appalachia established a micro-grant program to help fund queer and/or trans black, indigenous, and people of color-led (QTBIPoC) creative projects. There’s even a special partnership between Queer Appalachia and the Foxfire Foundation, an organization dedicated to the preservation of Appalachian traditions, in the works.

The next phase of outreach for Queer Appalachia also includes an explicit focus on serving queer and trans individuals impacted by the opioid crisis. Mamone told me by email that, “We’re so busy talking about how outrageous the numbers are, we’re not taking a closer look to see those Appalachian opioid numbers through a queer lens.” It is incredibly difficult to access support and treatment options in Appalachia, and it’s typical for community and family networks, including faith-based services, to fill in those gaps. But for queer and trans people who lack strong family structures or who have been excluded from communities of faith, recovery support can feel non-existent. Queer Appalachia hopes to help, first by working with licensed counselors and social workers to explore possibilities for creating an online recovery space that could feature peer counselors, or even just better connecting people to basic services, like providing transportation to addiction recovery meetings.

It’s tempting to use a modern framework for understanding the importance of Electric Dirt and its powerhouse combination of social media outreach and art that defies labels. The future of Appalachia might indeed be queer but it’s important to acknowledge that so is its past. Appalachia and similar rural spaces have always been geographies where queer people lived, but often, their experiences have been set against the assumption that queerness has a special relationship to urban life. This assumption can sometimes make it difficult to recognize that queer rural people in both the past and present have led legible and fulfilled lives.

In some contexts, rural spaces even offered queer people unique opportunities to test the boundaries of gender and sexuality. My favorite example of this will forever be the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which brought over three million young men into often-isolated rural settings between 1933 and 1942. Life in CCC camps revolved around physically demanding labor and male friendship, and government records indicate that drag shows, male beauty contests, and body-building were favorite pastimes. Few young men were punished for breaking norms or taboos. Forty-year-old journals like RFD and Lesbian Connection both had generous subscriber bases in rural areas. According to historian Colin Johnson, the best place to look for the possibilities of queer culture isn’t the cities but the woods.

It should be repeated, over and over again, that some of the region’s most successful, inclusive, and creative media-makers are queer and trans Appalachians.

Queer Appalachia and the impact of Electric Dirt stands out for its explicit focus on community building, resistance, and justice, but it joins a number of projects that have explored what it’s like to be queer in small-town America. Of those that focus on the South or Appalachia, Carol Burch Brown’s documentary project — It’s Reigning Queens in Appalachia — about the Shamrock Bar in Bluefield, West Virginia, and the Appalachian Queer Film Festival based in West Virginia are frequent stand-outs.

It should be repeated, over and over again, that some of the region’s most successful, inclusive, and creative media-makers are queer and trans Appalachians. We should remember this when we look out at the region’s media landscape and see whose stories get told, we should remember this when we consider who gets institutional support and funding, and we should remember this when we think about whose histories get preserved. And we should, whether inspired by gratitude or a desire to build a better world, seek to close the gap between who gets to be seen and who gets erased.

The success of the project is both celebratory and bittersweet. The enthusiasm surrounding Electric Dirt reminds us that Appalachian and queer people, and especially those who embrace both identities, are starved for positive representation. It’s a gift to look at an image that reminds you of your whole person, dignified and beautiful, but it is also a mercy that helps lifts a burden placed by years of poverty porn, years of extraction, and years of erasure that can remind you just how heavy a load you’ve been carrying.

Elizabeth Catte is a writer and historian from East Tennessee and is the author of the forthcoming What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia (Belt, February 2018). She holds a PhD in public history and is the co-owner of Passel, a historical consulting and community development firm.

To support more independent writing by and about the Rust Belt, become a member of Belt Magazine starting at $5 a month.

Y’all are doin it! Thanks .)