The evening of April 1, workers at the American Transmission Company noticed that two of its cables, which transmit electricity underwater across Michigan’s iconic Straits of Mackinac, had tripped within 30 seconds of each other. The company quickly shut off the network, but not before 550 gallons of toxic coolant fluid had leaked into the surrounding freshwater. More than a week later, state officials learned that the same ship that had caused the coolant leak had also collided with Enbridge Line 5, an oil pipeline that travels 200 feet below the Straits’ surface.

“Following a series of inspections,” Ryan Duffy, a spokesman for Enbridge, the Canadian oil giant that operates the line, said in a statement, “we have confirmed dents to both the East and West segments of Line 5.” Duffy added that Enbridge was “taking immediate action to assess appropriate, reinforcing repairs.”

Two hundred feet below the four-and-a-half-mile channel between Michigan’s Upper and Lower peninsulas, 23 million gallons of crude and NGLs (Natural Gas Liquids) flow daily through 65-year-old twin pipelines, threatening to poison the drinking water for 40 million people.

The company assured state officials the “structural integrity” of the pipeline was not damaged, but the incident rang out around the state: It was only the latest salvo in a high-stakes, years-long battle over Line 5. “This is not a pipeline controversy,” Liz Kirkwood, executive director of FLOW, a northern Michigan-based public policy organization, told Belt. “This is a controversy about protecting 20 percent of the world’s fresh surface water.”

Two hundred feet below the four-and-a-half-mile channel between Michigan’s Upper and Lower peninsulas, where Lake Huron and Lake Michigan converge, 23 million gallons of crude and NGLs (Natural Gas Liquids) flow daily through twin, 20-inch-diameter steel pipelines, threatening to poison the drinking water for 40 million people. For years, Enbridge and the State of Michigan, which holds the company’s contract, have been embroiled in controversy over the operation, which was built in 1953. In more recent months, a string of revelations — both on the condition of the pipeline and Enbridge’s failure to disclose information on said condition — have reignited the debate. In late January, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, a soft-spoken but deeply unpopular executive who oversaw the Flint Water Crisis, the most notorious water disaster in American history, signed an agreement that allowed the line to stay open.

“A governor who has been, I would say, largely responsible for the Flint crisis, you’d think would be more forceful on acting to protect clean water,” Mike Shriberg, a member of the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board and executive director of the National Wildlife Foundation’s Great Lakes Regional Center, told Belt. “There’s no good place for an oil spill, but when you’re talking about a worst case scenario — it’s an oil pipeline that sits in a body of water that can flow 10 times the rate of Niagara Falls … it’s a disaster waiting to happen.”

***

Line 5 begins in Superior, Wisconsin, a small port city in that state’s northwest corner, and extends east across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula before cutting sharply southeast across the Lower Peninsula to Sarnia, Ontario. The 645-mile route delivers propane to Michiganders — Enbridge claims it provides 55 percent of Michigan’s propane demand, a figure that amounts to about five percent of Michigan homes — but the route is primarily a shortcut across the Great Lakes to meet Canadian energy demand. The company does provide dozens of jobs in the state and claims it pays some $40 million annually in property and sales taxes, but Enbridge doesn’t actually pay the state directly to operate the line.

“Michigan takes all the risk and Enbridge makes all the money,” Ed Timm, a retired Dow Chemical engineer who has produced his own independent reports on the pipeline, told Belt. “What kind of a deal is that?”

Michiganders’ concern over Enbridge’s environmental threat is also rooted in the company’s own recent track record. In 2010, the company was responsible for the spill that sent 1 million gallons of a tar-like substance known as diluted bitumen (or dilbit) into the watershed in southwestern Michigan, the second-largest inland oil spill in U.S. history. But things came to a head for Gov. Snyder in March 2017, when dozens of protesters, including members of various Chippewa tribes, gathered along a busy commercial road a few miles outside of Lansing, holding signs calling for a Line 5 shutdown following revelations about the pipeline’s questionable condition. “Governor Snyder,” one enormous banner read, “Don’t ‘Flint’ the Straits!” One woman, taking the microphone, identified herself as a Kalamazoo-area resident who had witnessed the Dilbit Disaster. “This company has such a bad record,” she said. “They have no morals. They have no shame. All I’ve seen from Enbridge is lies.”

The protest took place outside the state’s Public Service Commission building. Inside the building’s Lake Michigan room, the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board — a 16-member panel representing interests from environmental groups, the tourism industry, the energy industry, and others — was holding a meeting over Line 5: board members, along with various Enbridge executives and representatives, crowded around long tables stacked with paperwork at the front of the room. Members of the public filled the rest, spilling into an overflow area where the meeting was broadcast on television. An Enbridge engineer, wearing a suit, gave a wonky slideshow presentation on the health of the line; at one point a middle-age man with shoulder-length hair got up from his front row seat, tailed by a young boy. A few minutes later the pair returned, naked except for their underwear and slathered in dark brown cake batter. The grandfather and grandson, members of the Odawa tribe, stepped up to the podium, positioned in front of a large aerial-view photograph of a cerulean Lake Michigan shoreline.

“We wanted to show you what the birds will look like, what the fish will look like, what the shoreline will look like if that pipeline breaks,” the grandfather, Fred Harrington, said in a gravelly tone. “If we continue to let it run and run and run year after year — it will break.”

“If we continue to let it run and run and run year after year — it will break.”

The public display of outrage came amid a sequence of disturbing developments over the line — and a snowballing public relations disaster for Enbridge. A month earlier, in February 2017, the Gaylord Herald Times broke the story that a recent report intended to measure the impact of zebra mussels, the “Biota Investigation Work Plan,” had also cited 18 areas along the Straits section of the pipeline where the protective coating surface contained gaps — a potential safety risk because bare metal is more susceptible to erosion, which can lead to a rupture. But when the revelations became public Enbridge downplayed the story: the locations identified in the report were “hypothetical,” Duffy, the Enbridge spokesman, told media outlets. In his presentation at the public meeting, Kurt Baraniecki, an Enbridge engineer, also denied there was evidence of actual coating gaps, maintaining a contractor writing the report had unintentionally used misleading language. Upcoming inspections, the company said, would prove the condition of the twin pipelines is as “good as they were when they were brand new,” according to reports.

In June new revelations came out, in the form of an analysis dubbed the Kiefner Report. Carried out by the Ohio law firm Kiefner and Associates as part of safety mandates following the 2010 Dilbit Disaster, the document demonstrated that Enbridge had known of structural problems — long spans of the Straits section that went unsupported by anchors, in plain violation of the terms of the company’s original easement — as far back as 2003. To critics, it was fresh evidence of decades’ worth of corporate neglect. “Enbridge didn’t do any maintenance on this thing for the first 50 years,” said Timm.

In late August, Enbridge disclosed that a recent investigation had indeed found two coating gaps; a couple weeks later the company showed inspection reports that documented eight. Then, In late October, Enbridge told the state it had known about at least one of the gaps since 2014: The previous statements assuring the public that no gaps had been found were a mixup caused by an “internal reporting issue…. At the time, these statements were accurate to the best of their awareness,” Duffy told reporters.

State leaders were publicly furious. Valerie Brader, executive director of the Michigan Agency for Energy and co-chair of the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board, demanded an apology. Bill Schuette, the state’s attorney general and leading Republican gubernatorial candidate (Snyder is term-limited and will leave office on January 1, 2019), who had already advocated for a shutdown, called on Enbridge for “a full and complete explanation,” declaring that “the faith and trust Michigan has placed in Enbridge has reached an even lower level.”

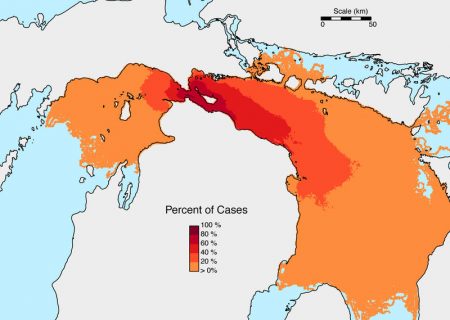

The University of Michigan’s Water Center looked at 840 simulated spill scenarios. This map, produced by the Water Center, shows the probabilities of where oil might go after a spill in the Straits of Mackinac.

Enbridge responded by promising better communication. Then in November the company provided the state a four-page report: recent underwater inspections had actually turned up 37* coating gaps — again expanding the scope of problems. Still more public outrage followed; Gov. Snyder, facing increasing pressure to act on the line, issued his own condemnation. The announcement was “deeply concerning,” he said in a statement. “I am no longer satisfied with the operational activities and public information tactics that have become status quo for Enbridge.”

Two weeks later, on November 27, the governor announced he had signed a new deal with the company, to the surprise of virtually everyone, including many on the governor’s own Pipeline Safety Advisory Board. With some new conditions, Enbridge would continue pumping under the Straits. Fielding a reporter’s question that afternoon, the governor praised the deal as “very proactive” and “milestone-driven.” It also marked a new chapter in the state’s relationship with the company, he said. “I think today’s agreement was a major step forward to saying, ‘this is serious stuff,’ and we believe we have Enbridge’s attention.”

Many saw it differently, including Kirkwood, the executive director of FLOW. “Every single day Line 5 continues to pump 23 million gallons of oil under our Great Lakes,” she said. “Make no mistake: this agreement does nothing to interfere with that.” To Kirkwood and other critics, the same governor who was responsible for the Flint Water Crisis had unilaterally cut a backroom deal with Big Oil that left the Great Lakes in potential peril.

***

Snyder’s November agreement with Enbridge outlined various mandates, including that the company shut down its Straits operation when waves reach eight feet high; consider new monitoring technologies; study an entire new tunnel project underneath the Straits; and meet regularly with the state to assess progress. The measures were hailed by the governor and state officials as temporary safeguards before a final decision on the pipeline is made this August. “It does not preclude, prejudice, or presuppose what the outcome is of Line 5,” Keith Creagh, director of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, told Belt. “What it does is it increases the [safety] rigors today.” Creagh also defended the apparently hasty execution of the deal as necessary because the governor had to act urgently. “In a perfect world we would have taken additional time to get broader input.”

Observers praised the agreement’s firm deadlines for progress reports and a requirement for new infrastructure under the St. Clair River, at the end of the line. But other aspects of the agreement were roundly panned as arbitrary measures apparently intended to score political points: the eight-foot-wave closure requirement, Shriberg and others said, was “not based on science” and dangerously permissive — even under waves of two or three feet, it can be impossible to recover oil from a spill. The provision that Enbridge conduct its own survey to assess three* different potential tunnel projects under the Straits also smacked of industry bias. “Which option do you think Enbridge will choose?” said Kirkwood. The option that would best serve residents, “or the one that will generate the greatest benefit for shareholders?”

Snyder created the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board in late 2015 for the sole purpose of advising him on Line 5, but the November agreement had effectively kneecapped the board. A couple weeks later the board met at a conference room inside the Causeway Bay Lansing Hotel for its quarterly meeting. In light of the governor’s deal, disillusioned board members proposed three resolutions, including one that Line 5 should be shut down until it’s further inspected and the coating gaps are fixed.

Thirteen of the 14 voting members were present. By a vote of five to one — seven , including Creagh, abstained — the coating gap resolution passed. The others also passed with multiple abstentions. The votes were an extraordinary rebuke to the governor — even if they proved only symbolic. On January 27 of this year Snyder sent a letter to his board: “Thank you very much for the resolutions sent to me following the December meeting,” he began. In the next paragraph he undercut the board again: Because less than a majority voted in favor, he pointed out, no resolutions had technically passed. Regardless, he would be rejecting all three measures — the Enbridge deal would proceed as signed.

Last week, amid the fallout from the latest dent revelations, Snyder called on Enbridge to decommission the existing line and construct a tunnel — “assuming studies show a tunnel is physically possible and construction would not cause significant environmental damage.” Critics, including Shriberg, praised the governor’s call for a decommission but questioned his advocacy of a tunnel project for an oil network that isn’t critical in the first place.

Shriberg also laid out another, more immediate case for temporarily shutting down Line 5, one that might be especially appealing to a governor who considers himself a technocrat. The original state easement that allows Enbridge to operate the pipeline stipulates that it must be coated. The previous revelations of gaps prove that it’s not, he said. “It’s operating illegally right now. It’s as simple as that.”

Sooner or later, Shriberg told Belt, it was inevitable the pipeline would be decommissioned: no piece of infrastructure lasts forever, especially a five-mile section of pipe that’s been sitting underwater for over six decades.

“Think of it this way,” Shriberg said: “Take a piece of metal and let it soak in water for 64 years. Would you trust that to carry oil through a body of water that delivers drinking water to 40 million people?”

Banner photo: Joe Brusky via Flickr.

Trevor Bach is a journalist based in Michigan.

To support more independent journalism by and about the Rust Belt, become a member of Belt Magazine, a non-profit publication, starting at $5 a month.