By Joey Horan

Dale Johnston and Danny Brown spent a combined 25 years in prison before being exonerated for crimes they did not commit.

Johnston’s conviction rested on the testimony of a hypnotized witness and an expert-for-hire with flimsy credentials. Brown’s on the testimony of a seven-year-old child.

Both men have filed suit against the state of Ohio seeking compensation for their years of wrongful incarceration, but the state won’t pay out. However, with last Thursday’s passage of House Bill 411 and the expected passage of its counterpart, Senate Bill 248, Johnston’s and Brown’s respective paths to compensation may have an opening.

Twenty-eight years and multiple claims for compensation later, Dale Johnston has yet to receive a dollar for the six years he spent behind bars. During that time he lost his family, his livestock, and a 53-acre farm.

The bill’s success comes as a relief to many exonerees who saw momentum on the legislation grind to a two-month halt after Ohio Speaker of the House Cliff Rosenberger resigned in April amid an FBI investigation into his “lavish lifestyle,” allegedly funded by payday lender lobbyists. And as the Ohio House delayed on voting in a new speaker, H.B. 411 faced mounting opposition from the Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association (OPAA), which had previously agreed to stay neutral on the bill.

Though legislators and proponents of the bill are now confident it will become law, Brown (pictured above) is not ready to let his guard down. “Too many people’s lives are at stake, and I don’t want to shoulder that burden,” he said. After a near two-decades-long fight for a declaration of innocence, he knows the squirrely hurdles one can face when seeking vindication — and compensation — under the law.

Johnston, for his part, has dementia and can no longer advocate as he once did for innocent people on death row. In his stead, his stepson-in-law, Bryan Corbett, testified on the senate floor last Tuesday to advocate for the passage of the bill. “Dale’s memory is now fading, and his health is declining. He has very little money and depends on our family for his care. He has suffered so much in his life, and he deserves some sense of justice and peace,” Corbett said.

***

The Case Against Dale Johnston

In 1984, Dale Johnston was convicted and sentenced to death for the grisly murders of his 18-year-old stepdaughter, Annette Cooper Johnston, and her 19-year-old fiancé, Todd Schultz, in Logan, the county seat of southeast Ohio’s rural Hocking County.

Corbett, Johnston’s stepson-in-law from his current marriage, said there had been bad blood between the Schultz and Johnston families prior to the October 1982 murders, and that the Schultzes were able to whip the town into a frenzy with scandalous accusations that Johnston was a jealous and lusting stepfather responsible for the killings. As a result, Logan grew “hungry for a hanging,” said Corbett.

According to Corbett, the prosecution was influenced by the public outcry against Johnston, and developed a theory that the rumored nudist who lived in a trailer far outside of town “came in from his farm, found the kids, brought them to his farm, killed them, cut them up, then drove them back into town to throw them into the Hocking River.”

To place Johnston in town at the time of the murders, prosecutors relied on the post-hypnosis testimony of Steve Rine, who, prior to what has been described as “suggestive hypnosis,” had given a different description of who he saw in the car. To place Johnston in the cornfield, where the limbs and heads of the young lovers were found buried (their torsos in the adjacent river), the prosecution relied on an illegally seized boot and the testimony of Louise Robbins, a self-declared “footprint expert” whose methods have since been thoroughly debunked by the scientific community. And to erase the possibility of any other suspects, prosecutors suppressed evidence that would have helped Johnston’s case.

“As soon as the trial was over,” Corbett said, “key people in the sheriff’s department and police department came to Dale’s lawyer and told him there were witnesses they didn’t tell him about. Sure enough, there were people who heard and saw things not consistent with the theory of the prosecution.”

One big for instance: Police dropped a lead on Kenny Linscott, who lived near the cornfield, was found lurking in the field as police carried out their search for the bodies, and had suffered a tremendous gash in his right arm on the night of the murders (corroborated by hospital records). Linscott’s wife reportedly told a deputy during the investigation that she “feared her husband might be the killer.”

The suppression of such evidence by prosecutors and police rose to the level of a Brady violation, a big no-no in criminal law that stems from a seminal U.S. Supreme Court Case, Brady v. Maryland (1963). In the Brady case, Pierce Reed of the Ohio Innocence Project said the court ruled that “when the government fails to disclose exculpatory evidence, or evidence that casts doubt on a defendant’s guilt, they’re violating that defendant’s right to a fair trial.”

The weight, or “materiality,” of such evidence was later clarified in United States v. Bagley (1985), in which the supreme court ruled: “The evidence is material only if there is a reasonable probability that, had the evidence been disclosed to the defense, the result of the proceeding would have been different.”

As a result, Reed said, it’s a high bar to prove a Brady violation has occurred. “When [the courts] recognize a Brady violation, it is almost always tantamount to innocence,” he said. “There are certainly cases where prosecutors and police fail to disclose something inadvertently. That won’t rise to the level of the Brady violation. They’re not going to rule that there was a Brady violation over something that is not a significant inaction by the state.”

Dale Johnston. Photo courtesy of the Johnston family.

In Johnston’s case, the Brady violation, along with the hypno-testimonies and the faulty footprint evidence, led to his conviction being overturned and his release in 1990.

Yet, 28 years and multiple claims for compensation later — plus convictions in 2008 of the real killer and his accomplice (Chester McKnight and Kenny Linscott, respectively) — Johnston has yet to receive a dollar for the six years he spent behind bars, mostly on death row. During that time he lost his family, his livestock, and a 53-acre farm that has since been developed on, according to Corbett.

Indeed, for the wrongfully incarcerated, freedom often comes with an asterisk. When Johnston was released, “a lot of people still thought he was guilty,” Corbett said. “He had a cloud of doubt hanging over him.”

And so Johnston stayed on the low, moving to Grove City outside of Columbus to live with his mother, who he cared for until her passing. He met his current wife through the Grove City First Baptist Church, where Corbett is the associate minister. The congregation took a while to warm up to him, Corbett said. “People here were scared to death of him.”

Now, at 84 years old, Johnston is being cared for by his wife, Roberta, Corbett’s mother-in-law. “It’s a struggle,” Corbett said. “The family is hoping for money so that we can provide adequate and decent care for him.”

***

Exonerated But Not Innocent

Despite his exoneration in 1990, Johnston’s first appeal for a declaration of innocence failed in 1993 because, under legislation written in 1986, claimants had to prove their innocence.

In other words, said Michelle Feldman, legislative strategist at the national Innocence Project, “you need to solve the crime yourself.” And Johnston’s theory of who committed the crimes — a butcher infatuated with Annette Cooper Johnston — was not enough to convince a judge.

“If there is a conviction and it’s based on improper actions by the state, the very least we can do is compensate the individual for that wrongdoing. It is that simple.” —Ohio Rep. Emilia Strong Sykes.

However, in 2003, the Ohio legislature amended the existing legislation to allow for claims to be made in cases where errors in procedure, such as Brady violations, occurred. That meant that Johnston could make his claim to compensation without having to prove his innocence, which was no longer a question by the time of his second appeal in 2012, four years after McKnight and Linscott had been convicted of the crime.

Johnston enjoyed brief validation in 2012 when he was declared wrongfully imprisoned by the Franklin County Court of Common Pleas. But after a ping-pong of appeals that lasted until June of 2017, the Ohio Supreme Court ultimately refused to hear Johnston’s appeal. Their reason: a 2014 decision in Mansaray v. Ohio in which the justices were called on to interpret a crucial piece of legislative language governing when an error in procedure must occur for a claimant to be eligible for compensation. They unanimously interpreted the words, “subsequent to sentencing and during or subsequent to imprisonment,” literally.

In other words, claimants like Johnston are not eligible to receive compensation from the state when their constitutional rights are violated before they are sentenced, not after, thus making Johnston’s avenue to appeal via error in procedure null and void.

Reed, who was a senior judicial attorney for Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor at the time of the Mansaray decision, said instead of interpreting the statute based on intent, as had been done in Ohio courts under the Supreme Court since 2003, “the court looked at the statute, looked at the language, and said this is what this means, it’s plain and simple.”

The absurdity of the interpretation rankles Reed. “The reality,” he said, “is there are almost no situations where that would happen.” As for Johnston’s case: “Even when it seems so clear what should be done, there’s a gap in the law that doesn’t permit him to seek relief because he doesn’t fit within this very narrow statue.

“In effect, what Mansaray did was return Ohio to pre-2003 law. The opinion doesn’t say that, but the reality of modern wrongful conviction cases is that the only people that are going to succeed under the Mansaray decision are the people who can prove their innocence.”

And though Johnston’s innocence is no longer in question, he cannot appeal based on innocence because of res judicata, in which a matter that has already received final judgment by a competent court cannot be brought again by the same parties.

***

The Opposition to Compensating the Wrongfully Imprisoned

House Bill 411 corrects the Mansaray decision by allowing exonerees who suffered Brady violations to make claims for compensation. Notably, under H.B. 411, Brady violations are the only error in procedure by which a claimant can seek compensation.

According to state Rep. Emilia Strong Sykes (D-Akron), a co-sponsor of the bill, compensating the wrongfully incarcerated is more than fair. “Wrongful imprisonment is, quite frankly, one of the most heinous offenses the state can do against a not guilty or innocent person,” she said. “If there is a conviction and it’s based on improper actions by the state, the very least we can do is compensate the individual for that wrongdoing. It is that simple.”

But for prosecutors in Ohio, it is not that simple. While the Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association (OPAA) worked closely with one of the bill’s co-sponsors, state Rep, Bill Seitz (R-Cincinnati), in drafting the legislation, and committed to stay neutral on it after reviewing the current draft in the fall of 2017, the association is now against the legislation.

“[We] still have concerns with awarding taxpayer dollars to individuals who have not proven actual innocence.” — Assistant Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Brian Gutkoski

Louis Tobin, executive director of the OPAA, explained the change in position in an email to Belt Magazine. He said the association changed course after the Ohio Innocence Project “publicly attacked the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor [Michael O’Malley], a member of the OPAA Executive Committee, merely because he raised concerns about this bill.”

The OPAA, Tobin said, later learned that Mark Godsey, the executive director of the Ohio Innocence Project, “is married to a woman who has a private law practice that handles civil wrongful imprisonment lawsuits,” and added that they “stand to benefit financially from House Bill 411 due to the fact that it expands the class of people who can seek wrongful imprisonment awards.”

In response, Godsey wrote in an email to Belt that the “alleged attack” came in the form of “a Facebook Post on the OIP’s Facebook page that informed those in the prosecutor’s county merely that he opposed the bill, and that if they disagreed, they should call and let him know.”

Godsey called the accusations of impropriety “nonsense,” saying that the Ohio Innocence Project “strictly adheres” to the National Innocence Network’s conflict of interest rules, which were “vetted by national ethics experts regarding relationships between state Innocence Project leaders and attorneys representing potential exonerees.”

Tobin of the OPAA added that advocates are “using Dale Johnston as the singular example of why we should be [supporting the legislation], but the legislation is casting a wider net than that.”

Godsey and other advocates say that accusation is based on a flawed calculation.

“They’re saying it’s going to be a flood of claims,” said Feldman of the national Innocence Project. “Really it’s going to be the exact opposite.”

That “wider net,” Feldman said, is still smaller than the net cast by the original legislation in 2003, when any error in procedure could lead to a successful compensation claim. “There have been a total of 31 claims since 2003, when the errors in procedure law took effect, and only six of those 31 claims were based on errors in procedure. And only one was a Brady violation.”

Additionally, in the name of fiscal responsibility, said Feldman, the bill includes an offset provision in which the state can recover any money claimants receive in separate lawsuits — namely, through the federal government’s statute on deprivation of rights — that surpasses the amount doled out by Ohio.

Reed of the Ohio Innocence Project said advocates have given up a lot in the drafting of this bill and “there’s no new argument” to justify the OPAA’s reversal. “The narrowing of procedural errors to just Brady violations is a significant one,” he said. “The offset provision is a significant one. Those two things aren’t necessarily in the interest of people seeking compensation after being exonerated, but that was a give on the part of the advocates of the wrongfully convicted.”

Now that the neutrality wheels are off, so are the gloves, and a lot of the sparring over the bill goes back to the essential question of proving one’s innocence.

Brian Gutkoski, an assistant Cuyahoga County prosecutor, who, it should be noted, successfully argued the Mansaray case in 2014, said he does not consider Brady violations to be “tantamount to innocence,” and in an email to Belt he quoted Attorney General Mike DeWine’s letter to the House and Senate, which stated, “[we] still have concerns with awarding taxpayer dollars to individuals who have not proven actual innocence.” (DeWine’s office confirmed that the attorney general’s specific criticisms of the bill were addressed via amendments. However, it did not confirm whether or not DeWine, the Republican nominee for Governor, remains opposed to the bill.)

Additionally, Gutkoski said the bill encourages the “Monday-morning-quarterbacking of a criminal case” and will make Ohio the only state in the country “that allows you to be compensated even if you were factually guilty of the crime.”

To back Gutkoski’s claim, Tobin provided Belt with a letter penned by OPAA’s president, Morris J. Murray, that cites two cases, one from 1988 and one from 1995, in which factually guilty people could potentially “be eligible for more than a million dollars in taxpayer money” due to Brady violations.

Critics of the legislation say the new law would be the most “liberal in the country,” despite the fact that within the spectrum of payouts — on the low end, Montana offers successful claimants educational aid, and on the high end, New York has no caps to the amount of money a successful claimant can receive — Ohio’s compensation ($52,625 per year of wrongful incarceration, plus attorneys’ fees and loss of wages and other expenses where proof of losses is available and compelling) is in the middle.

Rep. Seitz, the primary bridge to prosecutors during the drafting of the bill, is tired of the “squawking” on the Brady violations. “Maybe law enforcement and prosecutors need to go back to school and study the constitution,” he said. “They can avoid the problem by turning over all evidence for trial as they are constitutionally bound to do.”

Rep. Sykes added, “If you cannot prove your case, then that was a failure on you to do something. There is nowhere in our constitution that says you have to prove your innocence. It is on the state to prove you’re guilty.”

As prosecutorial opponents to the bill claim to be defending the taxpayer’s dollar, which is not their mandate as prosecutors, they are increasingly treating the new legislation as if it were a referendum on their jobs.

Tobin wrote in his email to Belt that the bill “questions the forthrightness of prosecutors.” And in a joint telephone interview with Tobin, Gutkoski said, “I think Ohio’s elected prosecutors should be relied upon to do their duty.”

***

“It is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer”

William Blackstone, the famous 18th century English jurist, wrote this foundational Anglo-Saxon principle: “It is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.”

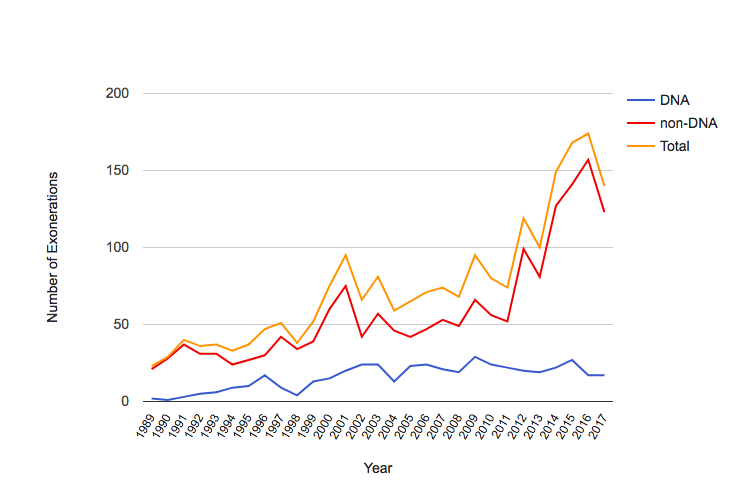

The increase of exonerations in the U.S. since 1989 suggests American prosecutors aren’t following Blackstone’s formulation. While one conclusion is that prosecutors are not always right, there is the darker suggestion that they are allowing themselves to be lead by concerns other than evidence.

Exonerations by year, 1989 – 2017, from the National Registry of Exonerations

That cynical arithmetic, Rep. Sykes argues, does not belong in our courts. “We do not work in a system where if I feel like I have a hunch, you should be locked up,” she said.

But in Danny Brown’s quest for innocence, a prosecutor’s hunch has held him in legal limbo almost 20 years after his exoneration.

Brown served 19 years of a life sentence for the 1981 Toledo murder of Barbara (“Bobbie”) Russell. His conviction was based on the eyewitness testimony of Russell’s son, Jeffrey, who knew Brown from previous visits to the home. Jeffrey Russell was six years old when the murder took place.

On the night of the murder, Bobbie was also raped, and in the case against Brown, the prosecution argued that the same person who committed the rape committed the murder. Yet, Danny was only found guilty of the murder.

In 2000, semen was recovered from the Lucas County Coroner’s Office and a DNA test revealed a match for Sherman Preston, who was already serving a life sentence for an eerily similar rape and murder in 1983. Based on the DNA evidence, Brown filed a motion for a new trial, which was granted, and he was released from prison in April of 2001. Julia Bates, the Lucas County prosecutor, then declined to retry Brown.

She did not, however, try Preston for the crime, and since then, Bates has refused to close the case or declare Brown no longer a person of interest.

That fact prevents Brown from seeking a declaration of innocence and compensation under current law, which requires that “the prosecuting attorney in the case cannot or will not seek any further appeal.”

Bates has defended her decision, citing her moral obligation to Jeffrey Russell’s testimony, which has several inconsistencies. In a 2012 CNN interview (Bates did not respond to multiple requests made by Belt for an interview), she said, “There still lives and breathes a person who was a six-year-old boy at the time of this crime who still maintains with every breath in his body that this is the man that killed his mother. And it’s very difficult to ignore that.”

Conversely, favoring eyewitness testimony over DNA evidence ignores a significant amount of scientific evidence showing that such testimony is unreliable. According to the Innocence Project, eyewitness misidentification has “play[ed] a role in more than 70 percent of convictions overturned through DNA testing nationwide.”

And while Bates stands by that eyewitness testimony enough to keep Brown from seeking compensation, she said in the 2012 interview there was still not enough evidence to retry him. “I’m not convinced that we have the necessary evidence to go forward. If and when we had sufficient, provable, credible, beyond-a-reasonable-doubt evidence, we would retry him. And if we never find good, provable, beyond-a-reasonable-doubt evidence, then we won’t ever retry him. He’ll remain free, he’ll remain out, but of course, he won’t recover money.”

Brown, a paralegal in his own right, has challenged the logic that he is not eligible for compensation “based on the metaphysical possibility that someday it may choose to prosecute him,” as summarized in an appellate court’s 2006 judgment against Brown.

Though Brown lost this appeal, Judge William J. Skow, the sole dissenting judge, wrote a scathing opinion of the majority’s decision and the prosecutor’s tactics:

“The majority accepts the state’s definition of ‘ongoing investigation’ to include passive waiting for any evidence in any case that has ever been opened, regardless of whether any actual, active ‘investigation’ is occurring. {¶ 30} Moreover, the majority, in its apparently wholesale acceptance of this evidence, has utterly failed to take into account that by December 30, 2004 (when the trial court issued its opinion and judgment entry granting summary judgment in favor of the state), nearly four years had elapsed since the DNA testing proved that the semen collected from the victim did not belong to appellant. At no time during that four-year period did the prosecution charge appellant with any offense in connection with Bobbie Russell’s death. We note that even as of today, approximately five years after the DNA testing, no new indictment has ever been handed down against appellant in connection with that case. This lack of activity on the part of the prosecution leads me to the inescapable conclusion that there was, in fact, no ‘ongoing’ investigation being conducted.”

Twelve years later, Reed of the Ohio Innocence Project echoes that dissent: “The family of that victim deserves an answer. Danny Brown deserves an answer. The people of Lucas County deserve an answer. All of these families are in limbo. I don’t see how that’s justice for anybody. And the exercise of discretion is one thing, but not to do anything, is not discretion, it’s inaction, it’s injustice.”

Though Bates is in control of the investigation — and copped to destroying evidence in a 2015 Blade article, saying the case “seemed to be over” — she is resigned to the fact that the only way to correct such potential injustice is to legislate it away. Her last words on the CNN interview are: “If that’s not fair, they should change the rules.”

H.B. 411 will change this rule, and Bates has joined Gutkoski and the OPAA in opposing the bill.

Danny Brown in 2001, hugging his attorney after being a granted a new trial. The decision would result in his release from prison after 19 years. Photo credit: Blade/Dutton

Brown’s case aside, Feldman of the national Innocence Project considers the current rule unfair to both parties. “It puts prosecutors in an impossible situation,” she said. In murder cases where there is no statute of limitations, it is tough to permanently close a case without a clear conviction. “There’s always a chance that evidence comes in the future,” she says. But for the exoneree who’s left waiting on the whims of a prosecutor who is hesitant to close a case, “they’re just left in limbo.”

To remove such inflexibility, H.B. 411 establishes a buffer period in which the exoneree must wait one year after exoneration to see if the prosecution will retry the case. If not, Feldman said, then the exoneree is eligible to make a claim of innocence and seek compensation. That said, “prosecution is free to file charges after that point.”

While advocates see this as fair and reasonable (and another point of concession made to prosecutors), Tobin of the OPAA worries that such a rule “leaves open the possibility that someone who is still under investigation will receive a wrongful compensation award and turn around and use that money as a defense, should they be tried again.”

Put another way, prosecutors don’t want to face a robust legal defense that money can buy.

But for the vast majority of exonerees who are unlikely to be retried, like Danny Brown, that money would be used to rebuild a life that was unjustly ruined by the criminal justice system. “The purpose of a lawsuit is to restore a person,” said Brown. “I’ve been sick. I’m broke. My Medicaid has been cut off. It’s a big struggle.”

Beyond that, Brown said, “I want an apology. I want the slate wiped clean.”

Banner photo: Danny Brown, who was convicted of a 1981 murder and released from prison in 2001, pictured here in 2015 at Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in Cincinnati, Ohio. With last week’s passage of House Bill 411, he may finally get compensated for his wrongful incarceration. Photo credit: The Blade/Jeremy Wadsworth.

Joey Horan is a writer based in Toledo, Ohio. He can be reached at [email protected].

Belt Magazine is not-for-profit and member-supported. To support more independent journalism made by and for the people of the Rust Belt, become a member of Belt Magazine starting at just $5 a month.