by Erin O’Brien

While the team at the Intermuseum Conservation Association (ICA) has worked on everything from outfits donned by screaming rock stars to paintings that hail from the 1500s, inside this unassuming Detroit Shoreway storefront, doing the job the right way means leaving no evidence you did anything at all.

In a word, the skilled craftspeople of the ICA erase. To the extent that is possible, they refresh what fire has scorched, dry out what water has drowned, and reverse the devastation of vandalism. For ICA’s staffers, invisibility is the highest goal, and being taken for granted goes with the territory. Yet the organization’s collective signature is something Clevelanders depend on in a cultural sense every day, often without even knowing it.

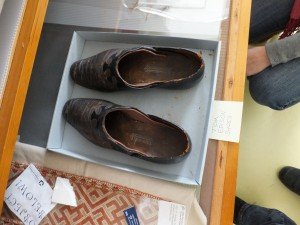

The ICA team works on an endless and ever-changing list of items from across the globe. Words don’t do the projects justice and photos aren’t much better. To explain what makes this place so remarkable, you have to start with something small and personal—like an old pair of slippers.

Such a pair is sitting in a workbench drawer awaiting shipment. Textile conservator Jane Hammond has completed her painstaking work without removing any of the slippers’ experience and character. Though clearly from another era, they are a completely ordinary pair of scuffs. Judging by the way the leather has formed to the shape of the owner’s feet, he slid these on when he woke each day and again when he prepared to relax at the end of it.

Eventually, when the slippers are carefully exhibited along with a host of other objects that belonged to Thomas Alva Edison, anyone viewing them at the Edison Birthplace Museum in Milan, Ohio, will smile inwardly and know that they have something in common with the man who invented the light bulb: a worn pair of slippers.

And so a tether is drawn over time and space; a connection is made. This is the subtle magic the ICA fosters and protects.

[blocktext align=”left”]Secrets are usually invisible as well, but the ICA craftspeople often discover untold stories in the course of their work.[/blocktext]Meticulous cleaning brings the thousands of stitches and tiny portraits depicted on an 1822 memorial textile back to life. Any layman viewing the work, which involves elaborate embroidery and painting on silk, will understand that the “accomplished seamstress” of yesteryear was an unparalleled craftswoman. After a treatment at the ICA, a 19th century Fresnel glass and brass lens is set to return to the lighthouse in Lorain, Ohio, with a shimmer it hasn’t had in, well, a hundred years.

Other items in the organization’s care demand a bit more space than a shoe box—or even the lantern room of a lighthouse—affords. Ironically, however, the biggest cultural treasures are often the ones we take for granted. Like a kid bounding down the stairs and wrapping his hand around the mahogany ball atop the newel post in order to pivot around it, there are cultural icons we Clevelanders depend upon without even knowing it. And if they weren’t there, our familiar cultural pivots would go awry.

Case in point: imagine a tragically neglected Free Stamp rusting at the corner of E. 9th and St. Clair like a defunct water tower. Fortunately, you don’t have to. This year, the giant painted steel structure, which rusts on the inside as well as the outside, will undergo extensive maintenance under the direction of the ICA. Next, imagine not being greeted by the massive mural, The City in 1833, in the main branch of the Cleveland Public Library. The ICA brought it back to life during the building’s renovation in the late 1990s. So to the credit of the ICA and its sponsors, the Free Stamp will continue to perplex and delight while the William Sommer mural continues to welcome library visitors.

The ICA helps maintain the unsung joy of the status quo, which is exactly the point—conservation and preservation work is most successful when it is invisible.

Secrets are usually invisible as well, but the ICA craftspeople often discover untold stories in the course of their work. Paintings Conservator Wendy Partridge knows when a starving artist painted over and over a canvas 500 years ago. Associate Objects Conservator Mark Erdmann can tell you a thing or two about how a mosaic tile was laid some 1,800 years ago in ancient Antioch. Staffers see the original brilliant colors of a needlework when the back, protected from the sun’s bleaching rays, is freed from the frame. They also know the difference between accidental damage and vandalism (and when to keep these details to themselves). Those lucky enough to stroll through their studio space, however, might get treated to a secret or two. Chatting with the staff as they work is a singular experience. And make no mistake—this place thrives on work. You won’t find pretentious scholars with leather elbow patches here. Work aprons are the preferred uniform and shoptalk centers around things like foxing and yellowed varnish and damaged plaster.

[blocktext align=”left”]Projects include Bono’s mirrorball man suit, an “odiferous” vinyl jumpsuit donned by Britney Spears, the first device used to record Elvis Presley’s voice, a silk afghan owned by Mick Jagger in the 1960s, and a gorgeous sari-inspired dress that belonged to Michelle Phillips.[/blocktext]ICA’s clients in Northeast Ohio include the family of famed Monuments Man James Rorimer, the Cuyahoga County Public Library, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame, which has forwarded items such as a 1920s-era sideline coat from the Green Bay Packers and Jerry Rice’s gloves. And while all of the projects here are quiet, some have a loud history. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame routinely does business with the ICA. Projects include Bono’s mirrorball man suit, an “odiferous” vinyl jumpsuit donned by Britney Spears, the first device used to record Elvis Presley’s voice, a silk afghan owned by Mick Jagger in the 1960s, and a gorgeous sari-inspired dress that belonged to Michelle Phillips. The list goes on and on, but (notably) does not include Lady Gaga’s meat dress, which ICA Executive Director Albert Albano bemoans as being, “so grossly altered it is virtually unrecognizable.”

The ICA often partners with other entities to cater to clients across the Rust Belt. They’ve tackled large murals in the historic Detroit Athletic Club, a David Smith sculpture, “2 Circle IV,” in Toledo and a massive public art installation in Pittsburgh’s transit system, “Pittsburgh Recollections” by Romare Bearden.

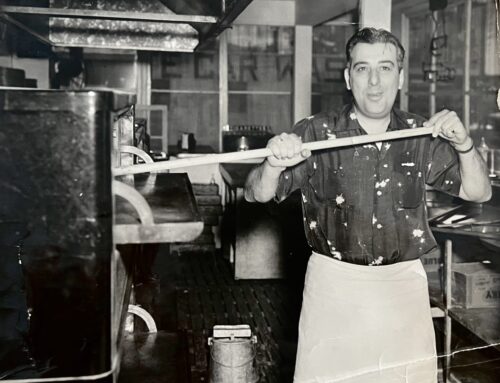

Some projects are so noteworthy they manage to pierce through the ICA’s invisibility. Last month, The Plain Dealer‘s Steven Litt penned an extensive article on the ICA’s efforts concerning a collection of salvaged depression-era artwork created courtesy of the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA). The subject is worthy of every word. After all, the draw of the federal art program only increases with time. Albano credits the universal attraction of the WPA projects to the energy and impetus that drove their creation.

“What I often like to spotlight,” says Albano, “is not only the art, but the energy and vision that brought it to realization. It was a vision of hope. It was a vision of the dignity of labor and the honorable life people were trying to live. This great spirit existed in spite of one of the worst economic decades in the whole history of the United States.”

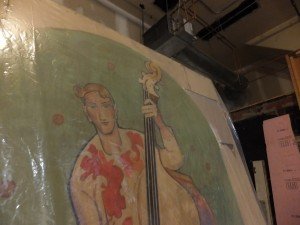

“The Spirit of Education,” 1939, William Krusoe, 20-by-32 feet, awaits its fate in the lower levels of the ICA.

The rebirth of Cleveland’s WPA treasure trove, however, is ongoing. Just last month while presenting at PechaKucha, the ICA’s Education Outreach Officer, Jennifer Souers Chevraux, fielded an enthusiastic query from St. Ignatius representatives about the massive William Kruesoe mural “Spirit of Education.” The homage to culture and education was salvaged from a scrubby Woodland Avenue storage facility, but only after a parking lot attendant at the Board of Education thought he remembered something about it. Whether or not the 20-by-32 foot mural finds a permanent home at the venerable Ohio City high school remains to be seen, but the prospect is strong.

Albano readily credits Lincoln High School alums Jan Lukas and Bob Pearl for spearheading the effort to save the mural. In describing their initiative, he aptly summarizes the profound responsibility all of us have in the art conservation and preservation movement.

“They are advocates for the artwork, which has no voice of its own.”

Erin O’Brien is a freelance writer in the Cleveland area.

EXCELLENT article about any EXCELLENT institution.