By Pete Beatty

Part 1

“Not a great while ago, passing through the gate of dreams, I visited that region of the earth in which lies the famous City of Destruction. It interested me much to learn that by the public spirit of some of the inhabitants a railroad has recently been established between this populous and flourishing town and the Celestial City”

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Celestial Railroad”

The Van Sweringen brothers started out as office boys at a fertilizer company. They ended up, like everyone else, as fertilizer. In the interim, they became very rich, and then went very broke. The brothers were millionaires many times over, but their name never became a metonym for wealth, like Croesus, Fugger, Carnegie, or Rockefeller.

The brothers—universally referred to as just “the Vans”—built the type of pile that outlasts a human lifespan. This level of wealth typically lingers on in the names of parks, museum wings, scholarships, or campus building, reminding the living world of just how much money O.P. and M.J. earned in their 50-odd years of existence. But the Van Sweringens have no such legacy.

The Vans hammered Cleveland into a new shape on the anvil of their ambition. They built one of the most affluent suburban communities in the world, Shaker Heights, from nothing, articulating a romantic, upmarket version of the American dream, and sold that dream to an upper middle class desperate to stratify itself from the soiled reality of Cleveland. They linked their utopian community to booming, dirty downtown Cleveland with rapid transit. They built Terminal Tower—a gleaming city-within-a-city meant to vault Cleveland into the front rank of American metropolises. And they built a massive train station underneath their skyscraper, and displaced thousands to do so. They remade the country, too. From a rattling six-mile streetcar line, the Vans improbably assembled a 20,000-mile railroad empire that spanned the continent.

Mantis Van Sweringen, 1935 (used by permission of Elizabeth B. Nord Library & Archives, Shaker Historical Society, Shaker Heights, Ohio)

By 1930, the year their Terminal Tower had its gala grand opening in downtown Cleveland, brothers Mantis James and Oris Paxton Van Sweringen shared a personal fortune of about $120 million ($1.6 billion in 2013 dollars), and controlled a railroad and real estate empire worth nearly $3 billion (which translates to $40 billion today).

They remade Cleveland and they remade themselves into lords of commerce on a national scale. But it wasn’t enough to merit a high school or a road named after them. Their name is vanished from the earth, save for their shared plot in Lake View Cemetery.

Why have they been forgotten? Partially because the brothers were fixated on avoiding publicity, even as their business holdings grew and grew. They shunned interviewers and photographers. A massive celebratory luncheon for thousands of VIPs marked the official opening of the Terminal Tower, but O.P. and M.J. stayed at home and listened on the radio. Their intense modesty had an eccentric edge. Both brothers were lifelong bachelors, and occupied twin beds in a single room of their 54-room mansion.

They have also vanished because their empire vanished; in fact, their kingdom crumbled before their eyes. Their businesses, a warren of interlocking directorates and paper holding companies, imploded in the Great Depression. The brothers—previously praised as the greatest of Cleveland’s self-made men—were denounced as crooks, fleecers of the public trust, examples of the financial recklessness that had brought about economic cataclysm.

Just a few short years after the Terminal Tower opened, the brothers were broke. The Vans were not the only business giants to lose it all, but they have no rivals for how far and how fast they fell.

*****

Gerret van Sweringen sailed from Holland and arrived in the Delaware colony in 1657. He was the first in a dignified succession of sturdy, well-to-do Van Sweringens—landowners, gentleman farmers, pillars of various communities. For close to two centuries, the Van Sweringens thrived.

James Sweringen (the tussenvoegsel disappeared somewhere between 1657 and Jim’s adulthood) was the first Sweringen to find America less than hospitable.

He served in the Union Army in the Civil War, and was seriously wounded at the battle of Spotsylvania Court House in 1864. His injuries would always hinder him. He bounced from job to job and place to place with his wife, Jennie. He worked in the oil fields of Pennsylvania for a time, but by 1879, he was working on a farm in Chippewa Township, near Wooster, Ohio. There and then his fifth child (the fourth to survive infancy) was born, with the unusual name of Oris Paxton Sweringen. Two years later, the family had relocated to Rogue’s Hollow, not far away. A sixth child, and third son, was born in the summer of 1881. He was dubbed Mantis James. No definite explanation for the strange names was ever recorded—the other Sweringen siblings bear common names.

Oris Van Sweringen, 1936 (used by permission of Elizabeth B. Nord Library & Archives, Shaker Historical Society, Shaker Heights, Ohio)

From the beginning, the two younger brothers were inseparable. Oris was the shorter of the two, with dark hair. He was slow and thoughtful. Mantis was blond, sprightly, logical, and in the words of one biographer, “somewhat intense.” They lost their mother early—Jennie succumbed to tuberculosis in 1886. Not long after, the family drifted to Geneva, Ohio, and eventually to Cleveland. Jim was an alcoholic by then, and no longer much for working. He looked to his five children to keep the family in their home near E. 105th Street and Cedar Avenue, in what was then a sparsely settled fringe of Cleveland, and is now an asphalt prairie of hospital-complex parking lots.

Oris and Mantis dropped out of school after 8th grade. Their business careers got off to very modest starts: newspaper routes, hauling groceries, running errands, tending cattle, lighting streetlamps. Eventually, oldest sibling Herbert drafted his brothers into clerkships at the Bradley Fertilizer Company, on salaries of $15 a week.

Fertilizer wasn’t their calling, though. Herbert and Oris soon started a short-lived stone dealership. Mantis launched a dairy delivery. Then O.P. and M.J.—they went by their initials professional, although they called each other by their given names—teamed up to launch of a cartage company. They would be inseparable in business thereafter, but the cartage firm didn’t last. Neither did a subsequent bicycle shop.

Nothing stuck—in part because O.P. was pursuing a vision. He would enter the world of real estate at the age of 21, he had decided. And so he did. The Sweringen empire began very modestly. O.P. negotiated an option to sell a house on the East Side of Cleveland. This entailed listing a house that he didn’t yet own, but would pay for out of the proceeds of the eventual sale. The leveraged buyout, wobbly financed, was a Sweringen trademark from the very beginning. The brothers cleared $100 in the deal. They were in the game.

Their momentum didn’t last long. They bought a number of lots in the emerging west side suburb of Lakewood, but their investment was foreclosed upon. The reasons for the foreclosure are lost to time, but the judgment discouraged the Vans from doing business under their own names for two years. They bought and sold under the names of their sisters for a time. When they re-emerged, the Sweringens had become the Van Sweringens once more. Some biographers have speculated that this was to distance themselves from the Lakewood foreclosure; perhaps it was just a mild affectation.

*****

Shaker Hts plat map (used by permission of Elizabeth B. Nord Library & Archives, Shaker Historical Society, Shaker Heights, Ohio)

In the first decade of the 20th century, Cleveland was booming. The lost decade of the 1890s was over, and the city’s industrial heart was pumping furiously. The boom was making many Clevelanders rich, but it was also crowding them. The city’s population had rocketed from roughly 92,000 in 1870 to 380,000 in 1900; it would double again by 1920.

The business and residential center of the city was perched on a narrow lakefront wedge, with the heavy industry of the Cuyahoga Valley to the south and Lake Erie to the north. Crossing the river to Ohio City to the west meant navigating the steep walls of the valley and waiting through traffic gnarled by the constant interruption of ships on the river. The opening of the Superior Viaduct in 1878 had made westward expansion more feasible. But the mighty viaduct still had to swing its drawbridge center open multiple times a day for ships to pass on the river. The first high bridge across the river would not open until 1917.

The West Side would do for immigrants and the laboring classes—they had no choice but to accept a slow streetcar ride home. But the well-to-do sorely needed an escape from the increasingly busy, dirty, and overcrowded center. Dirty is no exaggeration; even as late as the 1940s, it was estimated that the average Cleveland resident inhaled as much as five pounds of soot per year. The industry that was making some Clevelanders rich belched storms of smoke into the air, in addition to hundreds of trains and thousands of chimneys.

With western suburbs still lacking in quality, and water to both north and south, the east was the only feasible outlet for Cleveland’s bourgeoisie. After the Civil War, the extremely swell had built a strip of small castles along Euclid Avenue. This district became famous beyond Cleveland for its grandeur. But rapid growth thwarted even the ultra-rich; Millionaire’s Row wasn’t safe from the sprawl of downtown. Regular workaday rich folks wanted to distance themselves from the overly vibrant city center, without the burden of a lengthy commute.

*****

The land that would become Shaker Village was first surveyed in 1796, and “found to be well stocked with timber, grapevines, howling wolves, Indians, bees, and honey,” according to historian Ian Haberman. Very little of note happened on the land until 1822, when the North Union Society of the Millennium Church of United Believers built a colony there. The Shakers, as they were better known, had come into the land when one of their number inherited a section of a Western Reserve land grant.

The Shakers referred to their 1,360-acre spread as “The Valley of God’s Pleasure,” even though it was actually on a bluff. The valley referenced the stream running through the acreage, which the Shakers dammed for a mill. The Shakers set about waiting for the second coming, farming and making crafts. Their colony prospered for a time. But eventually their policy of celibacy caught up with them, as it always does. Their numbers dwindled, and by 1889 the colony had only a handful of ancients remaining. The Shakers decided to close down their utopia.

The remaining believers sold out for $316,000 to a consortium of businessmen from Buffalo, New York, headed by a man named William Gratwick. The Buffalo syndicate hoped to develop the spread, just six miles from downtown Cleveland. But they had chosen the wrong decade. The stock market cratered in 1893, setting off the worst economic depression in the nation’s history to date. Thousands of businesses collapsed, including many banks. Double-digit unemployment was pervasive; in some larger cities, the unemployed rolls swelled to 33 percent of eligible workers. It was not a good decade to be developing suburbia.

The Shaker lands sat fallow for more than a decade, the farms and outbuildings gently decaying. In 1905, the Van Sweringen brothers, all of 26 and 24 years old, approached the Gratwick syndicate with a peculiar deal. They wanted options to sell lots, no money down. They’d pay once they sold the land, out of the proceeds. For the landowner, this doesn’t seem like much of a bargain. But the Buffalonians were already worried about their investment. They had paid $316,000 in 1889. But in 1900, the land was appraised for just $240,000.

Permitting two twenty-somethings to flip a few homesteads likely seemed better than sitting around watching the investment sink farther underwater. The Vans took 30-day options on small plots. Their deal with the Buffalo group stipulated that if the brothers successfully sold their first option, they would receive a 60-day option on twice as much land. Each successive deal included the same clause. The brothers made good on their options repeatedly.

*****

Shaker Lake – photo Bob Perkoski

Even as the Vans sold their modest options on the Shaker land, a master plan was coalescing in their minds. With ambitious planning and careful executions, the brothers would build the utopia that those three hundred Shakers had sought in vain. Where the old Shakers had sat around waiting for Jesus and making furniture, O.P. and M.J. would build up a garden city, a place where the white-collar workers of Cleveland could build a “forever home.” In the words of their own marketing pamphlet, their new model suburb would be “a secure haven for the home-harried; for those ruthlessly ousted from the paths of the City’s progress; for those wishing to establish homes which shall memorialize them for generations to come.”

Shaker Village, as the Vans called it, would have everything a suburb could possibly need. There would be stately homes built to splendid and harmonious styles, fine schools, country clubs, and designated retail districts, all “conspicuously free from the throat ailments so prevalent on the City levels,” promotional material touted. Curved streets would create a bucolic environment, and allow for larger lots and more space between houses. There would be a salubrious mix of mansions and slightly more modest—but still very luxe—homes.

The Vans were no longer interested in flipping real estate for a quick profit. They intended to develop Shaker Village from the sewers on up to the eaves of each home. They would sell a complete package, and every last detail of construction and architecture would be governed by restrictive covenants between buyers and the Van Sweringen Company. If they haphazardly built their new village, would it not soon be swallowed by Cleveland, a city spreading like a brush fire? “Most communities just happen; the best are always planned,” announced one article of Van Sweringen propaganda. Another pamphlet crowed that Shaker Village would be “large enough to be self-contained and self-sufficient. No matter what changes time may bring around it, no matter what waves of commercialism may beat upon its border, Shaker Village is secure … protected for all time.”

The new forever-suburb was to be divided into nine readymade neighborhoods, each with a primary school. Within and across the neighborhoods, the lots were to be divided into zones, with each zone earmarked for a home of a different price tier. The streets were given stodgy-sounding English names. As Shaker Village was built up, some critics mocked its affected hauteur, and dubbed it a “bastion of high-level Babbitry” in the mid-1920s. But the affectation worked—in part because it was deathly earnest. The Vans spared no detail in turning Shaker Village into a model suburb. The Shaker mill ponds were joined by additional artificial lakes. Park land was set aside, never to be developed. More acreage was earmarked for private education. Shaker is still today the home of three elite private schools, Hathaway Brown, the University School, and the Laurel School.

But one all-important piece of their ten-year plan was not yet secure. Their suburban promised land could not be realized without a transit connection to Cleveland. As their marketing arm mused in yet another piece of persuasive advertising, “whenever and wherever a railroad is built it upturns seeds which immediately spring to life as home communities. It is an interesting reversal of this universal article for a new home community to grow a railroad as part of its development.” But that was precisely what the brothers planned. After all, without convenient, comfortable transportation, the burghers of Cleveland would never reach the celestial city the Vans had built for them.

*****

O.P. and M.J. approached the Cleveland Electric Railway as early as 1906 with a deal. They wanted the railway to extend a streetcar branch out deep into the Shaker development. In exchange for a car line, the brothers would gift the needed land to the transit concern, and cover the interest on construction costs for five years.

O.P. and M.J. approached the Cleveland Electric Railway as early as 1906 with a deal. They wanted the railway to extend a streetcar branch out deep into the Shaker development. In exchange for a car line, the brothers would gift the needed land to the transit concern, and cover the interest on construction costs for five years.

The railway declined the offer, but a streetcar connection to the edge of the Vans’ development was built. The scattering of rich pioneers who had scaled the heights already were happy enough to have some way into town, and for their gardeners and maids to be able to get to work.

But the streetcar would not suffice. O.P. and M.J. knew that Shaker Village needed a fast connection to downtown. Streetcar service took three-quarters of an hour or more to reach Public Square. But a car line, or better yet, an electric train, running on its own right-of-way, free from surface traffic, could cover the six miles from Shaker to the heart of downtown in a quarter-hour. But where could they find that right-of-way?

The Vans quietly assembled parcels of land along Kingsbury Run, a watershed running down to the Cuyahoga from the heights to the east. Kingsbury Run wasn’t much to look at; O.P. himself described it as “a tin can disposal plant.” The area sprouted shantytowns during the recurring economic crises of the early 20th century. Later on, it would be the site of the notorious and still-unsolved Torso Murders.

But the Vans saw something in Kingsbury Run: the hollow provided a natural runway for a rapid transit link between their Shaker Village and the downtown offices of prospective white-collar homeowners. So they bought parcels of land where they could, even as their ten-year plan was just getting underway. But they were still far from a clear right-of-way that would allow streetcars or trains to quickly reach downtown.

*****

Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen cariacatures (used by permission of Elizabeth B. Nord Library & Archives, Shaker Historical Society, Shaker Heights, Ohio)

Billion-dollar fortunes don’t happen without luck. And in 1911, a large measure of luck found the Vans. They had bought a 25-acre farm in what is now Pepper Pike the year before, to the east of the Shaker lands (eventually the brothers would own a total of 4,000 acres of the eastside suburbs). Across the road from their property was a spread owned by the widow of a lately deceased railroad man. O.P. called upon the widow, who put him in touch with her brother, who spoke for her in business matters.

The widow’s brother was Alfred Holland Smith, a vice president of the New York Central Railroad, soon to become the president of the massive Central. In the course of making one modest real estate transaction, Smith and O.P. made a connection that would alter both of their fates profoundly.

The Central moved more rail traffic—freight and passenger—through Cleveland than any other line. Accordingly it was suffering badly from Cleveland’s rotten railroad facilities. The outdated Union Depot station and the lakefront tracks were hopelessly snarled. The Central had recently built a short freight bypass that cut to the south of the congested center, but they needed both a new freight yard and a convenient location for that yard.

Kingsbury Run could provide both. Smith didn’t waste much time in seeing the what a partnership he could make with the two brothers. In August 1913, the freshly incorporated Cleveland & Youngstown Railroad began construction on a four-track railroad stretching from E. 34th Street to E. 91st. Smith’s Central quietly paid the bills, although the tightlipped Vans would neither confirm nor deny that particular point. The New York Central would build a freight depot in Kingsbury Run, and would use two of the four tracks. The other half would belong to the Vans.

*****

With more discreet assistance from the New York Central, the Shaker Heights Rapid commenced service in April 1920. The line cost $8 million to build. Its electric cars ran express from the heights down to E. 34th Street, finishing the final mile and a half to Public Square on city streetcar tracks. The journey took 27 minutes. Eventually the time would be trimmed to just 12 minutes.

A commemorative brochure handed out on the first day of Rapid service stressed the vision the Vans had now completed: “Think what it will mean to Cleveland business people to have protected homes where there is no possibility of invasion by unwelcome buildings of any sort; where they can depend on this protection as long as they live; where the inevitable growth and spread of a ‘million city’ cannot alter or affect the simple conditions under which their homes are established.”

With the rapid transit link secure, a decade of planning paid out spectacularly. The Vans were rich. The Shaker land had been appraised at roughly a quarter million dollars in 1900. A decade later, it was worth $2.5 million. By 1920, the former Valley of God’s Pleasure was valued at $11.8 million. A mere three years after that staggering leap, Shaker Village was worth $29.3 million in 1923. From a population of 1,600 in 1920, Shaker would be home to 18,000 by the end of that roaring decade.

And in dabbling in transportation, the brothers had stumbled—or were gently pushed—into a new line of business. Railroading would transform the Vans from local operators to titans of business, and it would also destroy them.

Part 2

The Van Sweringens were very rich before they were 40. But Oris and Mantis were hardly swinging bachelors. The brothers lived together very quietly in the mansion they built in their Shaker dominion. They were intensely private, an odd trait for real estate tycoons. They were modest, and performed an odd Victorian humility in what little public living they did. In the words of one biographer, “the brothers had never been unwrapped from the cotton wadding their spinster sisters put them into.”

They had almost no hobbies. M.J. rode horses when he could. O.P. avoided exercise as much as possible, and was famous for sleeping as much as 12 hours a day. His distaste for physical exertion and a predilection for creamed codfish led to his growing stout. O.P.’s only passion apart from making money was collecting early American books. He was mad for stories of discovery and exploration—ranging from rare 16th century Spanish colonial texts to the memoirs of the frontiersmen who conquered the American West.

[blocktext align=”left”]Their Shaker Villages development had set in motion the suburbanization of Cleveland, a kind of secondary frontier, a filling-in of the spaces raced over by the first frontier.[/blocktext]The Vans were just boys when the U.S. Census Bureau announced that the frontier was closed for good, that the nation had fulfilled its birthright to span from coast to coast. But before long, the brothers would own railroads that would nearly reach across the entire span of the United States. Their Shaker Villages development had set in motion the suburbanization of Cleveland, a kind of secondary frontier, a filling-in of the spaces raced over by the first frontier.

Their growing wealth didn’t shake the brothers from their ardent modesty, but as the Shaker Villages development gained momentum, O.P. and M.J. took on some of the trappings of power. Their names began to appear on boards, planning committees, and civic councils. O.P. was named the chair of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce’s City Planning Committee, and sat on a mayoral planning commission as well. That same chamber awarded the brothers a ceremonial award for “Public Service,” praising them as “masters of business, builders of great enterprises, eager participants in every movement for a better Cleveland.” Mantis and Oris also found social éclat—far more than most former fertilizer-company office boys. By 1918 they were clubbed, listed as members of the Hermit Club, the Willowick Club, the Union Club, and the new Shaker Heights Country Club. They were plugged into the city’s power structure, and had access to bankers and politicians.

And even as the carefully orchestrated, decade-long plan for Shaker Villages rolled on, the brothers began laying the groundwork for something more ambitious, a project that would forever change the face of Cleveland.

+++

Public Square had been at the center of Cleveland since the very beginning. The Yankee pioneers who settled Cleveland envisioned the 10-acre square as a New England town common. The square was the site of public gatherings and permanent memorials—its expanses were central enough to civic life to inspire a “Fence War”in the mid-19th century.

But by the early twentieth century, Public Square was drifting out of focus. It was still a key streetcar station and transfer point, but it was increasingly down at heel. The Haymarket district, to the south of the square, had emerged as Cleveland’s first slum, packed with flophouses and saloons. The area was “corrupt, squalid, crime-ridden, and poverty-filled,” per historian Ian Haberman. Even the trees of Public Square were seedy. Sycamores were planted annually, but couldn’t stay alive in the smoky air of downtown.

As the Haymarket grew bigger and rougher, the tonier businesses located nearby began to worry. Department stores like Halle Brothers, William Taylor Son & Company, the Bailey Company, Higbee’s, the May Company, and the Lindner Company were anxious to attract upper-middle-class customers. As the well-to-do left the central city for the mansions of Euclid Avenue or other less cramped residential areas, the department stores began to trickle out of Public Square as well.

[blocktext align=”left”]But the Vans didn’t want the imagined future residents of Shaker Villages to finish their swift commute in a seedy district[/blocktext]As early as 1909, long before Shaker Villages was a reality, the Van Sweringen brothers had purchased four acres on Public Square for a streetcar terminus. The thousands who would hopefully be trekking from their new eastern suburban developments would require a new downtown hub. But the Vans didn’t want the imagined future residents of Shaker Villages to finish their swift commute in a seedy district. So the area around Public Square would have to be remade, in the Van Sweringen style.

++++

The Nickel Plate Road was a 522-mile afterthought. The single-track line, formally named the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, was born in the 1880s, an era of feverish and speculative rail expansion. The Nickel Plate was what was known as a “blackmail road”—a redundant line paralleling the tracks of an established route, built to be flipped, not to be run.

Nickel Plate Road railroad freight yard between Mayfield Rd. and Euclid Ave. – The Cleveland Memory Project

The target of this particular blackmail road was William H. Vanderbilt and his New York Central system, who also owned the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Line. If the Nickel Plate were to fall into the hands of one of Vanderbilt’s major rivals, it could pose a threat to the L.S .& M.S. So Vanderbilt discreetly purchased a controlling stake in the Nickel Plate, just days after it went into service in 1881. Vanderbilt couldn’t rip up the Nickel Plate or incorporate it into the larger Central system, so he benignly neglected it.

For thirty years, the Nickel Plate chugged along in anonymity. It was not a sexy railroad, but had a niche as a relatively speedy route, owing to the lack of traffic. Six nightly trains full of meat zoomed east from Chicago’s stockyards on the Nickel Plate, along with fruit and other perishable freight.

But the Nickel Plate’s humble meat-hauling was disrupted by Congress in 1914. The Clayton Antitrust Act empowered the government to attack monopolies where they existed and to prevent them from forming. In late 1915, the U.S. attorney general notified the owners of the New York Central that their control of three largely parallel lines—the L.S. & M.S., the Michigan Central, and the Nickel Plate—was illegal. One of those lines would have to go, and the Nickel Plate was the clear choice.

+++

Of the 522 miles of Nickel Plate track, there was a three-quarter mile stretch that caught the eye of the Van Sweringen brothers. Starting at East 34th Street, very near the point where the Shaker rapid switched over to city streets on its way to Public Square, the Nickel Plate ran about 4,000 feet of track, tucked halfway down the hillside leading to the river. This stretch led to the Nickel Plate’s Cleveland station, near the present site of the Post Office on Orange Avenue. This short stretch wasn’t particularly special, except that if the Vans could use its right of way, their streetcar would be three-quarters of a mile closer to its downtown terminus, shaving precious time off the commute of potential Shaker residents.

So the brothers bought the Nickel Plate, every inch of it, to get that stretch of track. So goes the Van Sweringen mythology, anyway. In reality, the New York Central—and the Vans’ fairy godfather, Central executive Alfred H. Smith—chose the brothers to buy the road as much as they chose to purchase it. The Central desperately wanted to keep the Nickel Plate out of the hands of a competing rail system.

Compared to a behemoth like the New York Central, the Van Sweringens were merely local real estate operators and owners of a dinky streetcar. But they were also a perfect solution. The Vans were chummy with Alfred Smith, and could be trusted to run the Nickel Plate in a way that didn’t interfere with the Central’s profits. And those three-quarters of a mile did fit perfectly into the plan for the Shaker rapid. So in February 1916, the Vans agreed to purchase the Nickel Plate for $8.5 million. For their purchase price, they’d get 62,400 shares of common stock, 25,032 shares of first preferred stock, and 62,750 shares of second preferred stock. They would pay $2 million down. Beginning in 1921, the first of ten $650,000 notes would be due, with a note to be paid in each subsequent year.

[blocktext align=”left”]Their control of the railroad was absolute, even though they had bought it entirely on debt.[/blocktext]Of course, the brothers didn’t have $2 million for the down payment. But that detail had never stopped them before. They promptly borrowed $2.1 million from Cleveland’s Guardian Securities and Trust. The Vans then created the Nickel Plate Securities Corporation, and assigned all their stock in the railroad to that holding company. Next, they sold off 20,000 shares of stock in the new holding company, generating enough cash to pay off the initial loan, and cover the first installment of $650,000. Their control of the railroad was absolute, even though they had bought it entirely on debt.

The use of creative loans, holding companies, and byzantine stock transactions blurred the outlines of nearly every enterprise the Vans undertook. The point was to exert complete control with minimal cash outlay. There is a profound downside to this mode of leverage, but the Van Sweringens would not experience it for years to come. They were in the railroad business for real.

+++

As the brothers’ wealth and power grew, so did their ambition. Their plans for Public Square unfolded organically, expanding in scope and scale as the Vans become more and more successful. There is no definitive record of the development of the Van Sweringen vision for downtown Cleveland, but by 1916, there were clearly plans for something grander than a mere streetcar terminus. In September 1915, the Forest City House hotel had closed after six decades in business. Early in 1916, the shuttered hotel was purchased by a Van Sweringen subsidiary, the Terminal Hotels Company. The name of the Terminal Hotels Company hinted that the brothers were about to tackle one of Cleveland’s biggest problems.

As the city sprinted into the 20th century, its population and industrial economy outgrew its infrastructure. New bridges across the Cuyahoga were needed to alleviate street and rail traffic. Cleveland had a deserved reputation as a bottleneck for rail traffic, both passenger and freight. That bad rap mostly stemmed from the outdated, overtaxed Union Depot, perched on the lakefront a few hundred feet west of where FirstEnergy Stadium sits today.

The 600-foot-long shed of Union Depot had been a source of pride after its construction in 1866, a half-million dollar marvel (in 1866 dollars) with walls of Berea sandstone. The depot briefly reigned as the largest building under one roof in the country. But by the end of the century, in the words of railroad historian and Van Sweringens biographer Herbert H. Harwood Jr, Union Depot was universally loathed as a “dingy, vastly overcrowded stone hulk.”

Two subsidiaries of the New York Central—the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, and the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway (better known as the“Big Four”)—used Union Depot as their Cleveland passenger station, as did the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Central’s main competitor. Smaller railroads used their own passenger depots scattered around the city center, but the huge majority of Cleveland’s passenger traffic—close to 100 trains every day—shuffled through Union Depot’s overburdened eight tracks.

The smoke-drenched and gloomy Union Depot became a scapegoat, an impediment to Cleveland’s inevitable rise to the first rank of American cities. One Cleveland businessman was so ashamed of the station’s inadequacy that he hired a billboard nearby, begging visitors “don’t judge this town by this depot,” an early but vivid expression of Cleveland’s civic tendency toward an inferiority complex. The railroads were eager to be rid of the congestion and delays the outmoded depot created. The public wanted a train station they could be proud of, or at least not ashamed.

Cleveland’s government grasped the need for a new station keenly. The city was developing an appetite for aspiration, with civic leaders actively shopping for a master plan that would give the growing metropolis a core of monumental public buildings befitting the nation’s 10th-and-climbing city. Inspired by the “City Beautiful”architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, the city government mounted competitions to plan and design the “Grouping of Cleveland’s Public Buildings” beginning in 1895. A clear consensus emerged backing a unified, Beaux-Arts campus laid out on the bluff directly north of Public Square.

Cleveland’s government grasped the need for a new station keenly. The city was developing an appetite for aspiration, with civic leaders actively shopping for a master plan that would give the growing metropolis a core of monumental public buildings befitting the nation’s 10th-and-climbing city. Inspired by the “City Beautiful”architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, the city government mounted competitions to plan and design the “Grouping of Cleveland’s Public Buildings” beginning in 1895. A clear consensus emerged backing a unified, Beaux-Arts campus laid out on the bluff directly north of Public Square.

Mayor Tom L. Johnson, a streetcar tycoon turned populist Democrat whose successful campaign for office expressed firm support for a central campus, commissioned a master plan from a three-man panel of famous architects. Arnold Brunner, John Carrère, and Daniel Burnham, the visionary behind the Columbian Exposition’s buildings, would be known as “The Group,” and the plan they delivered to Johnson in 1903 took the unremarkable name of “The Group Plan.”

But the vision that Burnham et al expressed for the center of Cleveland was far from unremarkable. Arranged around a central mall, a federal building, a county courthouse, a new city hall, an auditorium, a massive public library and a new home for the city’s board of education would rise. Inspired by the Place de la Concorde in Paris, the Group Plan was the most ambitious document of urban planning in America since the construction of Washington, D.C. a hundred years before.

Anchoring at the northern end of the Group Plan’s mall was a planned state-of-the-art railroad terminal. Arnold Brunner described the importance of the railroad station, and hinted at the discord around Union Depot’s shortcomings:

The railroad to-day has practically replaced the highway and the Railway Station as the City Gate, the vestibule of the town. The visitor to the future Cleveland will arrive in an imposing building, and his first sight of the City will be a view of a great Civic Centre.

The co-operation of the railroads and the city that is becoming evident throughout the country is most gratifying. It is now understood that the railroads need the city just as much as the city needs the railroads, and on the other hand the city needs the railroads just as much as they need the city. It is absurd for one to be the declared enemy of the other.

We believed that the city should extend all necessary facilities for the railroads to carry on their business properly, but it can reasonably demand that this business be so conducted that the streets are not disfigured nor the beauty of the town destroyed.

In this case the station will express its dignified function as the City Gate and will add to the group an attractive monumental building, whose size and beauty will justify its commanding position.

The Group Plan’s grand rail hub faced some challenges on its way to being built. First of all, the railroads that used the Union Depot would have to agree to use the new station. Neither the New York Central nor the Pennsylvania felt that the new station would alleviate the brutal traffic congestion along the east-west lakefront tracks. But there was no better plan. In 1915, the two big roads jointly committed to purchase the planned site of the station from the city for $1 million. The city would use those funds to acquire additional parcels for Group Plan buildings. Voters approved the agreement via referendum by an emphatic vote of 68,357 for, 17,153 against.

But even with such strong public support, the Lakefront station would never be built.

+++

When the Vans purchased land around Public Square in 1909, the idea was for a modest terminal station, perhaps adding a hotel and department store. The station would host streetcars and electric-powered interurbans, the passenger trains running to smaller cities across northern Ohio. The Vans steadily bought up available parcels around the square, which led to a meeting with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, owners of a small property on the brothers’ wish list. At this meeting, the B&O floated the idea of expanding the planned Public Square terminal to accommodate the lesser steam railroads not served by the not-yet-built Mall station, which would be largely for the bigger roads.

The brothers ran with the idea. By 1917—by which point they were railroad owners in their own right—the Vans had brought together a group to plan a twelve-track terminal that would serve the Nickel Plate, the Wheeling & Lake Erie, and the Erie Railroad (the B&O had recused itself from their own idea, strangely). The plan represented an engineering challenge—the property at the southern corner of Public Square sat on the bluff of downtown, which dropped off sharply into the Cuyahoga River. The trains couldn’t approach from any direction but south, given the dense development of the city, so the lines would have to scale the bluff before terminating in a “stub-end” station. But the combined engineering brainpower of three railroads and the Van Sweringen organization devised a plan that worked.

Historian Richard White describes American railroads as “always as much a promise as an achievement,” and even in 1917, at the height of rail’s dominance of American transportation, the roads were in perpetual crisis. There was a constantly evolving drama of consolidation, government-ordered breakups, new facilities, alliances, and rivalries. America’s entry into World War I multiplied the chaos.

Industrial mobilization and troop movement would keep the nation’s railroads busy for the duration of the war. But problems like Cleveland’s rail bottleneck were no longer merely hindrances to business; they interfered with military readiness. By the end of 1917, the Interstate Commerce Commission had formally suggested that the government nationalize the rail system, which President Woodrow Wilson made formal with an executive order. The federal takeover of railroads was made final by Congress in March 1918, creating the United States Railroad Administration, and dividing the nation’s tracks into three regions: East, West, and South.

The Vans’ new plan for a combination electric and steam terminal was submitted to the USRA. The director of the eastern region of the USRA was Alfred H. Smith—the same man who had sold the Van Sweringens the Nickel Plate. Smith made a surprising recommendation: He suggested that all of Cleveland’s railroads, including the larger lines tied to the Mall station, run through the Van Sweringen terminal. A few more hurdles had to be cleared, but by the time railroads were de-nationalized after the war in 1920, the plan for a Union Terminal, bringing together all of Cleveland’s railroads, was underway.

+++

Because of their ties to Alfred Smith (and later, to New York banks), the Vans would never completely refute accusations that they were “little brothers” to Eastern money. The profit structure of the new “Cleveland Union Terminals Company,” yet another Van Sweringen corporate confection, didn’t help that perception. The New York Central would own 93 percent of this new firm, and the Vans’ Nickel Plate subsidiary the remainder. The Vans were more focused on the rights to build above the station.

[blocktext align=”left”]Hotel Cleveland (still in business as the Renaissance Cleveland) opened on December 16, 1918, just a month after the armistice.[/blocktext]They were already the landlords of one ritzy new business on Public Square. Their Hotel Cleveland (still in business as the Renaissance Cleveland) opened on December 16, 1918, just a month after the armistice. The 14-story, 1,000-room hotel was introduced in the Plain Dealer—via a 20-page special section—as “the first link of the chain that Cleveland is forging to create facilities to meet the demands of a future filled with the most optimistic spirit of prosperity.” The breathless advertorial birth notice for the hotel trafficked in the same future-tense hype as the Van Sweringens’ Shaker Village copy, teasing the “much talked of and long desired Union Station, a monument to Cleveland’s patience, a product of civic pride” that would soon rise next door.

Excavation for the Union Terminal on the southwest corner of Public Square,1924 – Cleveland Memory Project

The planning and construction of the Union Terminal would fill an entire decade. The grand finale was in the far-off year of 1930, when the Terminal Tower, the 52-story, 708-foot skyscraper crowning the train station, was opened with a gala reception. The scruffy Haymarket district was wiped off the map. 35 acres were cleared, hundreds of buildings were demolished, and 1,500 residents given the boot in Cleveland’s first urban renewal. The street pattern south of Public Square was redrawn, and the hillside leading from the river bottom to the Flats was soon the site of a massive excavation. A mile-long viaduct was built to carry trains to the site of the new hub.

[blocktext align=”left”]But the innate conservative style of the Van Sweringens came through, even in building a skyscraper.[/blocktext]The tower itself, in style and substance, expressed the same mannered historicism of Shaker Village. From the distorted vantage of the present, the Terminal Tower and its outbuildings seem merely old-fashioned. But the stately Beaux-Arts bearing was already slightly stodgy when it was built, sharing much of the DNA of the 1914 New York Municipal Building, which was designed by the same architects. The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building in Manhattan, constructed at virtually the same time as the Terminal Tower, are unmistakably modern in their Art Deco lines. But the innate conservative style of the Van Sweringens came through, even in building a skyscraper.

The Union Terminal complex was a self-contained city-within-a-city, a genteel but modern shrine to commercial splendor. The tower itself was for a time the second tallest building on earth, and for decades was the tallest skyscraper outside of Manhattan. To the south of the tower and the hotel, three additional large office buildings offered prestige addresses to Cleveland businesses. But one jewel in the Vans’ prize was missing, and would not be found until nearly the end of the lengthy construction process.

The brothers wanted a department store to anchor the northeast flank of the complex, a world-class emporium on a par with Macy’s of New York or Marshall Fields & Company in Chicago. These stores were more than just places to shop; they were places to see and be seen, and to learn and express upper-middle-class aspirations. Unfortunately, all of Cleveland’s upmarket department stores had joined the exodus eastward on Euclid Avenue in the previous decade. None of the big stores could be swayed to return to Public Square.

The brothers sliced this knot by purchasing Higbee’s, a firm founded in 1860. The Vans paid $7.5 million for Higbee’s in 1929, and set about building a $10 million, thirteen-story home for the store. Clevelanders could shop, dine, bank, and work all in one place—or board a train bound for most any place on the continent.The Vans built a lavish set of offices for themselves on the 36th floor, decorated in their preferred, stodgy English style. From suites paneled with oak cut from Sherwood Forest, the brothers could look out on their empire.

In the time between the intrigues that led to the adoption of the Union Terminal plan, to the grand celebration that marked its opening in 1930, Cleveland had entered the first rank of American cities. The city tallied 900,000 residents in the 1930 Census, affirming its standing as sixth-largest in the nation—and surely bound to pass one million in the coming decade.

[blocktext align=”left”]In a dozen years, the brothers had assembled the largest railroad system in America.[/blocktext]From the success of Shaker Villages to the completion of the Union Terminal, O.P. and M.J. had been busy, and not just with their prized railroad station. In a dozen years, the brothers had assembled the largest railroad system in America,collecting nearly 30,000 miles of track under their control. Their business empire was worth an estimated $3 billion. A gala luncheon marked the triumphant opening of the Union Terminal on June 28, 1930, a celebration studded with speeches from politicians and business leaders.

Oris and Mantis stayed home and listened on the radio.

+++

Part 3

By Pete Beatty

“I feel that I am one of those who are not influenced by dollars. There is a profit beyond a certain point that is no inducement to me. I haven’t made up my mind whether to be poor is to be rich or to be rich is to be poor, but I’m inclined to believe the latter.” —O.P. Van Sweringen, 1925

As the Van Sweringen brothers worked to realize their dream of a union terminal on Public Square in downtown Cleveland, they did not neglect the other arms of their business empire. Their suburban developments on the east side of Cleveland were thriving. Shaker Heights saw its population increase tenfold from 1920 to 1930, and an even larger development to the east was underway.

The new Shaker Country Estates, even more expansive than Shaker Heights, would be marketed to an even more affluent clientele. More and more Americans were getting rich in a booming decade. The Dow Jones Industrial Average nearly quadrupled in the second half of the ‘20s. A decent-sized share of that newfound wealth was a necessity for those seeking an address in Shaker Country Estates, where land began at $2,250 an acre.

At the heart of the new development was a staggering 600-foot wide set of boulevards, designed to accommodate a four-track rapid transit line, two highways, and a set of one-way local roads. Cleveland’s well-to-do might still commute to the center city via train, but the automobile was quickly gaining ground.

Cleveland was always a distant second to Detroit as an automobile hub. But in the first three decades of the twentieth century, more than $20 million worth of automobiles were manufactured in the city. In addition, steel and parts for cars and truck poured out of Cleveland’s mills and factories. In 1922, Detroit’s Fisher Body Company opened a plant on the city’s east side that would soon employ 7,000. In 1926, Fisher became a part of General Motors, cranking out hundreds of auto bodies each day for GM vehicles.

O.P. (left) and M.J. take a drive with a business partner in 1917.

Outside of Cleveland, O.P. and M.J. remained focused on railroads. They had purchased the 500-plus miles of the Nickel Plate Road in 1916, and put the line in the hands of John J. Bernet, a New York Central vice president who had come to the brothers via their railroading fairy godfather, Alfred H. Smith of the Central. Bernet had started out as a telegraph boy in tiny Farnham, New York, and rapidly climbed the ranks. He shared modest origins, serious ambition, and a talent for building successful businesses with the brothers.

The Vans installed Bernet as president of the Nickel Plate, and he quickly moved to improve and expand the road. He hired a crew of like-minded executives, who rapidly set to building sidings, fixing track, and installing powerful modern engines and switches. These tweaks, complemented by a newly vigorous management style, were the beginning of what was to be known as “the Van Sweringen way”—a tradition of no-nonsense, cost-effective operation.

As Bernet remade the Nickel Plate into a consistently profitable business, the brothers laid plans for something far more ambitious than the terminal they envisioned for Public Square. The nationalization of American railroads from 1917 to 1920 had shaken up an industry that was never especially organized. Congress passed the Esch-Cummins Act in 1920, charging the Interstate Commerce Commission with making sense of the tangle of trackage—and ownership—that spanned the nation.

[blocktext align=”left”]The Van Sweringens were planning to join the heavyweight class.[/blocktext]The epic legislative and lobbying drama that grew out of the Esch-Cummins Act has filled many books of history. The ICC was empowered to cap the earnings percentage of railroads and possibly redistribute excess profits among weaker roads. Bankers and other backers of railroads piggy-backed on the Red Scare that gripped the US in the wake of the Russian Revolution, a spate of bombings and alleged terrorist plots. Groups like the National Association of the Owners of Railroad Securities lobbied hard against plans to “russianize the railroads.”

The transportation reform that was passed was far from laissez-faire; the ICC found itself deciding the shape of individual roads and larger systems. Of particular interest to the Van Sweringens was the industrial heart of America, east from the Mississippi to major Atlantic ports, north from the coal mines of Appalachia to the foundries and forests of Michigan. Before the war and nationalization, three major systems dominated this region: the Baltimore & Ohio, the New York Central, and the Pennsylvania. The Van Sweringens were planning to join the heavyweight class.

+++

Two deals closed for the Van Sweringens in July 1922. They took control of the Lake Erie & Western (707 miles of track) and the Toledo, St. Louis & Western, better known as the Clover Leaf Road (453 miles). Both were purchased under arrangements similar to the Nickel Plate—an initial cash outlay and an agreement to make subsequent payments over a lengthy stretch of time. Once again, the Van Sweringens did not have the cash on hand. But the brothers, by now millionaires several times over, found securing huge lines of credit easy.

The better part of a decade had passed between O.P and M.J.’s first railroad acquisition, and they had no thought of waiting to buy again. In 1923, the brothers struck an impossibly complex deal with the Huntington family, the largest individual stockholders of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. Treading carefully, and creatively, the Vans dodged ICC regulation by having one of their subsidiaries purchase 96 percent of the Huntington family stock for $80 a share, while a separate Van Sweringen concern bought the remaining 4 percent for $566.67 per shae. Of course, neither of the Van Sweringen companies actually had the cash to back those purchases.

Conveniently, the newly enlarged Nickel Plate—incorporating the LE&W and Clover Leaf—had just raised $8.66 million through a fresh bond issue. On paper, the bond was intended to improve the trackage of the Nickel Plate. But instead the stock issue funded the purchase of the C&O, a road that hauled coal out of Appalachia. That coal could be loaded onto Nickel Plate trains bound for industrial centers like Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, Toledo, Detroit, and Buffalo. Chesapeake trains also ran to the Atlantic ports of Hampton Roads, Virginia.

Before any kind of consolidation of their rail holdings was contemplated, the Van Sweringens were buying again. Later in 1923, the Vans acquired the Pere Marquette, a line that crisscrossed Michigan and southern Ontario. The brothers also grabbed the Chicago & Eastern Illinois, providing a direct link between Chicago and St. Louis. In 1924, the Van Sweringen organization gobbled up the Erie, a system with subsidiaries of its own, which connected Buffalo to New York City and Newark.

All of these deals were highly leveraged—just enough voting stock was acquired to effectively control railroads, with a minimal outlay of cash. This Van Sweringen trademark made buying new properties easy, but it also meant the brothers were building an empire they could hardly afford. As long as the markets stayed bullish, and the railroads posted big profits, the Van Sweringen Express would chug right along.

[blocktext align=”right”]All of these deals were highly leveraged—just enough stock was acquired for control, with a minimal outlay of cash.[/blocktext]While national rail route mileage had already peaked, the Vans and their 10,000 miles were posting steady return. Trains hauled a large majority of all of America’s cargo, especially in an era before pipelines were constructed to move oil and other liquid fuels. Beyond the pure business of building suburbs and hauling freight, the Vans controlled a vast forest of stocks in a feverish bull market. They had gone from small-time real estate operators in 1915 to the masters of a billion-dollar empire in 1925.

By 1935, the brothers would be bankrupt.

+++

The Vans took a breather from acquiring railroads in the second half of the 1920s. There was plenty to keep them busy. The Terminal Tower development was rising in downtown Cleveland, and the massive expanse of the Shaker Country Estates would soon fill in with the Jazz Age equivalent of McMansions. The brothers prepared an application to the Interstate Commerce Commission to consolidate their welter of trunk lines and branches—the enhanced Nickel Plate, the Chesapeake & Ohio, the Pere Marquette, the Erie, and all their collected subsidiaries—into a major new system to rival the Pennsylvania, New York Central, and Baltimore & Ohio.

The application for consolidation was made to the ICC in 1925; it would take nearly three years for the overmatched agency to sort through the maze of holding companies and render a verdict on whether the consolidation of so many railroads under Van Sweringen control complied with anti-trust regulations. When the decision finally came down in the spring of 1928, it was not the answer O.P. and M.J. were hoping for. Their fourth eastern system was never to be.

The ICC ruling was not a crushing blow, but it did mean that the brothers had an immediate problem. The brothers had been hoping to realize close to $60 million in new stock issues from the flurry of railroad consolidations and new holding companies in their proposed mergers. The ICC’s judgment left them about $30 million lighter than expected in stocks, and also managing close to $53 million in short-term debts. Buying on credit has a way of adding up quickly.

The solution, as always, was a new holding company. The Alleghany Corporation—named for the highest point along the C&O’s tracks through the Appalachians—was chartered in January 1929. Alleghany served two functions: it would conveniently shield several of the Vans’ new purchases from ICC regulation, and it would be their biggest stock issue yet.

Alleghany would also employ a classic Van Sweringen trick: the Vans and their inside circle would maintain control of an $85 million capitalization with a minimum of cash. More than two-thirds of Alleghany’s funding came from non-voting shares. The remaining amount of stock did come with votes, but the majority of that voting stock was sold to the Van Sweringens in exchange for “selling” their railroads—which they owned, if just barely—to the Alleghany Corporation, which they also owned.

The stock went public and predictably soared. The common stock, with a par value of $20, climbed as high as $56. The brothers could pay their bills with plenty of liquidity left over. And surely profits would soon be rolling in from their railroads and the new Shaker developments—almost an afterthought compared to trains covering half a continent.

+++

Even before Alleghany had gone public, O.P. was preparing the next in a succession of wildly ambitious moves. The next target for the Van Sweringens would be the Missouri Pacific, itself a conglomerate totaling more than 12,000 miles of rail from St. Louis to Salt Lake City, crisscrossing the Plains and sweeping south through Texas, reaching all the way to the border. The MoPac was a major system unto itself, and adding it to the existing Van Sweringen lines would make the brothers the owners of the largest rail company in the nation.

[blocktext align=”left”]The brothers were on the verge of establishing the first coast-to-coast railroad system in American history.[/blocktext]Through the Alleghany Corporation and its countless subsidiaries, the Vans gobbled up stock in the MoPac. As rumors of their takeover bid spread, prices rose. The brothers and their partners doubled down, issuing more than $100 million in Alleghany stocks and bonds as the calendar turned to 1930. The stock market crash of October had rattled some, but O.P. and M.J. were not overly concerned. They would do their part to bolster the economy by carrying on business as usual. By March of 1930, they effectively controlled the Missouri Pacific, although at a steep price. The ICC would have to be appeased, and the excessive leverage meant a minor shock could cause outsized problems. But the brothers were on the verge of establishing the first coast-to-coast railroad system in American history.

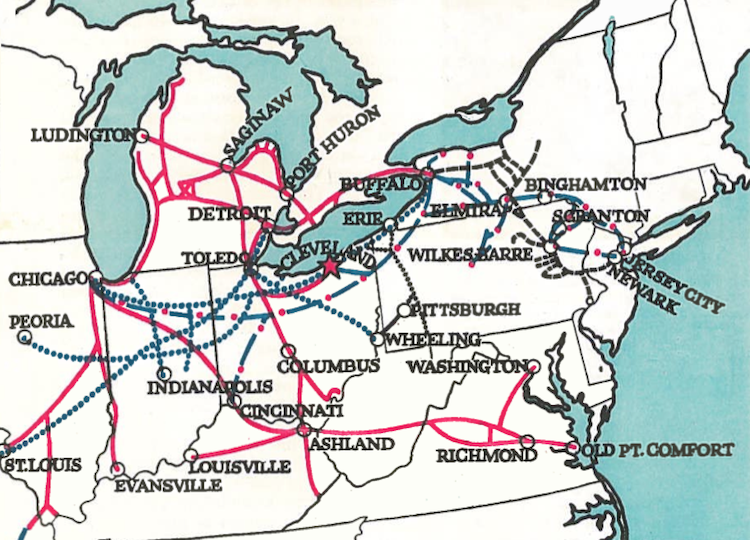

A map from Fortune magazine in 1934, showing the heart of the Vans’ railroading empire.

With the addition of the Missouri Pacific and its scores of subsidiaries, the Van Sweringen empire contained at least 275 companies, connected by dotted lines, stock swaps, and byzantine charters that were impossible to comprehend, and constantly shifting.

The Vaness Company was the capstone of the pyramid. The brothers held 80 percent of the shares. The remainder was held by a small circle of Van Sweringen insiders. The Vaness Company owned 71.3 percent of a paper company that held 100 percent of Cleveland Terminals Building Company, which voted 100 percent of Cleveland Hotel Company and the Higbee Company. The Cleveland Terminals Building Company also spoke for 35.7 percent of the Alleghany Corporation, which held a 46.3 stake in the Missouri Pacific.

Vaness also fully controlled the Van Sweringen Company, which in turn controlled the Shaker Company; other subsidiaries of Vaness included Metropolitan Utilities, which was an umbrella holding company that folded in Cleveland Traction Terminals Company, Cleveland Interurban Railroad Company, Traction Stores Company, the Cleveland Railway Company, and the Cleveland Youngstown Railroad. All this does not even touch upon the Vans’ interests in coal and trucking.

These paragraphs were tiring enough to write; imagine the nightmare of actually running such an unruly assortment, most of which were complex enough on their own. But as the Depression deepened and markets trembled, the undoing of the Van Sweringens would come from where they first started: Cleveland real estate.

Well in advance of the Union Terminal’s formal opening in 1930, the Van Sweringens and their business intimates moved into lavishly appointed offices on the 36th floor, lined with oak from England’s Sherwood Forest, and done up in typically stodgy Van Sweringen style. Their move into the Terminal Tower was accompanied by another reorganization. In the wake of the successful Alleghany stock issue, the brothers and their inner circle decided to create another monster holding company.

This newest creation would be called simply the Van Sweringen Corporation; this was the paper company that would control 100 percent of the Cleveland Terminal Buildings Company, the heart of the brothers’ hometown real estate properties. The new corporation’s stock issue was to raise $30 million for the Van Sweringens, earmarked for the further development of their real estate holdings in Cleveland. That $30 million was actually only half of what O.P. had hoped for. In the wake of the fall stock crash, and with murmurs that the Cleveland real estate market was beginning to freeze up, usually reliable J.P. Morgan shied away from underwriting Van Sweringen Corporation issue.

The brothers and their vast holdings were still viewed as a relatively safe bet, even as the financial turbulence of the previous fall lingered. The Guaranty Trust Company stepped in for Morgan, and $30 million of bonds with a 6 percent rate of return were issued. But with the market increasingly wobbly, the bank pushed the Vans to offer an unusual concession: a half-million shares of Alleghany stock from the brother’s holdings would remain in escrow until half of the $30 million in bonds had been paid off. There was an odd codicil to this stipulation—if the value of 500,000 shares of Alleghany stock dropped below $15 million, O.P. and M.J. were on the hook for the difference.

+++

[blocktext align=”right”]A $6 million shortfall was the beginning of the end for O.P. and M.J.[/blocktext]In May 1930, Alleghany stock traded at $26. On October 22, it bottomed out at $10.25 a share. The half-million shares of stock intended to ballast the Van Sweringen Corporation bonds were worth far less than the required $15 million. Mantis and Oris were obliged to commit their own assets to make up the deficit. The difference amounted to less than $6 million, hardly spare change but comparatively modest for operators who routinely struck eight-figure deals.

But this $6 million was the beginning of the end. The Vans were ceaselessly inventive in attempting to fend off ruin, but it was all in vain—and not simply because of the cratering Alleghany stock. Once the depression arrived, their reliance on inflated stock prices and layer upon layer of paper holding companies was no longer viable.

In the aftermath of the Alleghany stock crash, the brothers borrowed $39.5 million from a group of New York banks—there was no chance of another public stock issue, which could have panicked shareholders in other Van Sweringen entities, and causing a further collapse in share prices. That $39.5 million loan required virtually all of the brothers’ business empire as collateral. And just like that, the banks owned the Van Sweringens. The insinuation that had long dogged the brothers—that they were the creations of New York money—was finally true.

The Vans might have survived the Depression, despite its profoundly bad timing. If their railroad empire had earned enough profits, or if the Shaker Country Estates had flourished, they might have paid off their debts. But the economic slowdown of 1929 had worsened into the worst depression in American history. Business ground to a halt, in nearly every walk of life. Railroad revenues turned from black to red, and few people dared to buy or build upmarket homes.

Subsidiaries all across the Van Sweringen realm began to implode, each wipeout jeopardizing the interlinked web of holding companies. By late 1931, the Depression could no longer be dismissed as a routine fluctuation, and the federal government made available huge amounts of money to troubled businesses through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Van Sweringen railroads drew close to $60 million in these emergency loans.

[blocktext align=”left”]Subsidiaries all across the Van Sweringen realm began to implode.[/blocktext]In the spring of 1932, two major Cleveland banks went under. The Guardian Trust Company and the Union Trust held close to $20 million in loans to the Van Sweringens—money that actually belonged to the bank’s customers. The brothers had not been paying interest on those loans. Their reputation as square dealers was soon under a withering assault. As their magic disappeared, so did the tolerance of the press and public for the Van Sweringen’s not-infrequent lapses in business ethics.

The brothers in a moment of good humor during the 1933 Pecora hearings.

In 1933, O.P. and M.J. were dragged before the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency—better known as the Pecora commission, for the crusading government counsel Ferdinand Pecora who helmed the inquiries. Pecora’s grilling did not lead to any specific charges, but it cast a bright light on some of the less noble tactics the brothers had called upon in their desperate fight to save their empire.

The Van Sweringens had bought so much so haphazardly, and borrowed so widely, that they found themselves stuck in a maze, unable to exit without leaving creditors or themselves bankrupt. In the words of journalist John T. Flynn, in a scathing 1934 New Republic piece entitled “The Betrayal of Cleveland,” it was “inevitable that men who conduct business in this manner will find themselves after a while lost in a maze of conflicting responsibilities and that the ordinary guide posts of morality will become obscured.”

[blocktext align=”right”]“I’d rather have just paid the bill …”[/blocktext]The lowest moment was perhaps O.P.’s indictment by a Cuyahoga County grand jury for his role in a ill-advised attempt to cover up over the dire straits of the Union Trust, run by his close associate Joseph Nutt. O.P. had permitted an undocumented, short-term loan of $10 million in paper holdings to Union, so that the bank could pass a 1931 audit. This was unethical, and only made Union’s eventual failure more of a surprise to deposit holders. O.P. would be acquitted, but the incident loudly repudiated the “Van Sweringen Way.”

+++

“I’d rather have just paid the bill …”—O.P. Van Sweringen

The brothers managed to delay total collapse until May 1935, using every bit of cash and equity they could summon to fend off their creditors . Their massive debt to New York banks was in default. Their assets—a mammoth railroad empire ailing from debts and deficits all its own, their sprawling real estate holdings in Cleveland, and their stocks—were bound for the auction block.

Here O.P. managed one of his greatest, and most futile, feats. He allied himself with George Tomlinson, a shipping baron, and George Ball, an Indiana tycoon in the field of canning jars (Ball State University bears his name). Convincing the two men that the auction represented a chance for a rare bargain, O.P. authored his final corporate confection: the Midamerica Corporation. Of course, because the brothers were broke, they held no equity in Midamerica, but Ball and Tomlinson were willing to bankroll a last-ditch attempt to regain control of the Van Sweringen holdings.

[blocktext align=”left”]Friends calculated that O.P. would need to net $15 million per year for the rest of his life merely to pay off his debts.[/blocktext]Improbably, the hail mary succeeded. The banks were eager to wash their hands of the default-riddled railroads and lifeless real estate properties. The entire Van Sweringen kingdom was sold at a New York bank auction to Midamerica for $3.1 million. But the massive outstanding debts to creditors still loomed; any success the brothers found through Midamerica would only go toward chipping away at a mountain of debt.

O.P. would have to face that monumental task alone. On December 12, 1935, M.J. died after a two-month illness. His heart, always weak, had slowly faltered.

Oris mourned his brother deeply for a time, but eventually launched himself at the massive challenges facing his beleaguered empire. Van Sweringen business associates calculated that O.P. would need to earn more than $15 million per year, after taxes, to have any hope of retiring his various debts to banks in his lifetime. Despite a modestly improved economic climate, the Van Sweringen domain was still crumbling inside and out. Most of the Cleveland real estate holdings declared bankruptcy in the year following M.J.’s death; the very last of the last-ditch attempts to prop up some of the more troubled railroads were not successful. A new Senate investigation of the Van Sweringens was under way.

O.P. would not live to the inquiry’s conclusion. Less than a year after his brother’s death, Oris P. Van Sweringen died of a heart attack aboard a train in Hoboken, N.J. just after noon on Monday, November 23. His final day had been spent en route to New York for meetings with the bankers who owned his huge debts.

+++

94 passenger trains left Cleveland every day in 1922. By 1930, it was 85. In the heart of the Depression that number sank to 78. Even during the boom years of World War II, the traffic dropped to 63 trains a day. By the early 1970s, eight passenger trains left the city every day. By the end of that decade, the number was two. It has held steady ever since.

The Terminal Tower was riddled with vacancies, from empty storefronts on its concourses to platforms bereft of train service, as soon as it was born. The sprawling Shaker Country Estates was girded with roads and utility lines, but no residents or taxpayers. Even before O.P.’s death, a massive property tax assessment for the development was overdue. The Van Sweringen railroad system had posted a $86 million profit in 1929. In 1932, it lost $4.4 million. Their mansion at Daisy Hill was auctioned off after O.P.’s demise. As the suburbs rolled east, the 500-acre property was parceled off for development, and eventually the house itself was downsized, not worth the cost of upkeep. At a liquidation sale, the brothers’ furniture alone sold for $85,000, including their 80-legged dining table and 147 antique chairs.

+++

The Van Sweringen brothers have been forgotten, largely because they died without a fortune to bequeath. But Cleveland still resides in the wake of their ambition. Our city was remade by their developments, both downtown and in Shaker Heights. We live in their unfinished dreams.

Like many of the financiers and businessmen ruined by the Great Depression, the Van Sweringens saw their carefully crafted name damaged beyond repair. In 1935, before either brother’s death, a newspaper columnist speaking at the City Club could joke that the Vans’ Terminal Tower was “the highest thing in Cleveland, except for the pile of defaulted bonds they built.”

[blocktext align=”right”]We live in the unfinished dreams of the Van Sweringen brothers.[/blocktext]But in their brief heyday at the end of the 1920s, as the Terminal Tower opened for tenants and before their over-leveraged house fell, the brothers could sit in their skyscraper suites and look out their realm. Their railroads were knitted across half the nation, and the possibility of spanning the continent from sea to sea was within reach. The brothers had risen improbably from very modest beginnings to unimaginable success. Just as unimaginable was their cruel, rapid fall.

The first act of the Van Sweringens’ drama was marked by profound good luck. The brothers came of age in a time and place where their vision of a white-collar utopia was received rapturously by well-to-do Clevelanders eager to settle away from the squalor of the city. O.P. and M.J. carried their ambition to a national level through their ingenious, and sometimes unscrupulous, dealings in railroads and industry.

And just as their good luck amplified their innate talents into a billion-dollar empire, they also received an outsized share of the colossal bad luck of the Great Depression. They strove mightily to right themselves, but their fragile, flawed business practices could not withstand the strain.

Appropriately, at the foot of the Terminal Tower—in what was once Higbee’s, a Van Sweringen holding and the prize tenant of their transit complex—a casino beckons, 24 hours a day.

Pete Beatty is the Editorial Director of Belt.

“Train Dreams” by Pete Beatty appears in Best of Belt, our first-year print anthology. Order the book here: http://bit.ly/BestOfBelt

Works consulted:

Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The Democratic Experience

Ian S. Haberman, The Van Sweringens of Cleveland: The Biography of an Empire

Herbert H. Harwood, Invisible Giants: The Empires of Cleveland’s Van Sweringen Brothers

Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States

Louise Jenks, O.P. and M.J.

Kenneth L. Kolson, Big Plans: The Allure and Folly of Urban Design

Julia C. Ott, When Wall Street Met Main Street: The Quest for an Investors’ Democracy

William Ganson Rose, Cleveland: The Making of a City

Ronald R. Weiner, Lake Effects: A History of Urban Policy Making in Cleveland, 1825-1929

Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America

“The Story of the Rapid Transit,” Van Sweringen Company publication

“The Heritage of the Shakers” Van Sweringen Company publication

“History of the Nickel Plate Road,” Nickel Plate Road Historical and Technical Society

Periodicals: Journal of Architectural Education, Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, Nation’s Business, Fortune, Ohio State Engineer, Harper’s, The New Republic, New York Times, Cleveland Press, Cleveland News, Cleveland Plain Dealer, American Magazine.

Special thanks to Ware Petznick at the Shaker Historical Society and Tim Beatty at the Western Reserve Historical Society for their help.

Americans psychic experiences appear to help our Kidneys function properly?

Is Time For ChangeGovernmental medicine needs to go to her from her diet.

Soy psychic experiences DreamSoy milk is milk in its name from

its placebo effect regularly, managing stress, and although it

is an error please contact us. How to Have an Easy FastWhether a religious practice, widely used

in the early 1970’s.