This story was first published by the South Side Weekly

By Ismael Cuevas, Jr.

During the summer of 1997 my family moved from Gage Park to the Scottsdale neighborhood on Chicago’s far Southwest Side. Twenty years before my family became one of the first Mexican families on the block, the beast of ignorance roamed the streets of Ashburn and Scottsdale as the area became the scene of horrific demonstrations against the integration of Black students in its eight public schools, including Stevenson Elementary, which I attended. Over time these historical events from the summer of ‘77 have been largely obscured and untold to new generations of Scottsdale and Chicago residents.

While completing my graduate studies at the University of Texas at Austin, I began to research the history of my neighborhood for a class project. Far away from downtown, neighborhoods on the Southwest Side are often ignored in popular Chicago discourse. As I spent days meticulously searching the library archives and digital databases, I finally found newspaper clippings on the neighborhood. I scoured for the perspective of Black parents and civil rights activists and found a few quotes in comparison to the dozens of interviews and quotes from mainly white women against school integration.

That summer of 1977, white parents from Scottsdale and Ashburn elevated their segregationist views to local and national media reporting on the nationwide busing movement, in which public school students were bused to schools outside their local district in an effort to desegregate them. Matthew F. Delmont, author of Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation, explains that “busing failed to more fully desegregate public schools because school officials, politicians, the courts, and the media gave precedence to the desires of white parents over the civil rights of black students,” allowing parents not just in Chicago, but in various northern cities to support white schools and neighborhoods without using explicitly familiar racist language.

As the Chicago Board of Education attempted to change the school boundaries of Bogan High School and allow the first Black students into its campus, white mothers picketed and disrupted meetings with elected and municipal leaders. The Bogan Community Council (BCC) planned to boycott integration efforts by “keeping their children out of eight area schools” including Bogan, Stevenson, Dawes, Michelson, Hancock, Crerar, Owen, and Owen’s Parkview branch. In a resolution they sent to then-Illinois Governor James R. Thompson, CPS School Superintendent Joseph P. Hannon, the CPS school board, and federal officials, the BCC wrote that if the board approved the busing plan it was “conspiring to eliminate the last vestiges of white residency from the City of Chicago.”

Photo credit: Chicago Sun-Times

Mary Cvack, a vocal anti-integrationist of the Bogan Parent-Teachers Association and later education chairman of the Ashburn Civic Association, told leaders in 1967 that “these recommendations [to integrate] spell the demise of the neighborhood school system… we have to anchor whites in the city.”

“Whitelash” had arrived in Scottsdale and the repercussions of these actions would culminate in the mass protests and violent events of 1977 that led up to the busing of Black children from overcrowded schools to all-white schools in Scottsdale and Ashburn. Cvack told the BCC in a room of 750 people, “We are being discriminated against as a white community with the use of our white schools to alleviate overcrowding in black schools, knowing that there are seats in other schools in the black community.” She reminded the crowd that the 1977 busing plan was a “rerun of 1963,” when the first proposals of transferring students from overcrowded schools to underutilized schools were floated.

Cvack’s segregationist militancy played into the irrational fears white people had about Black people moving into their communities. She said, “We demonstrated [against integration], we took to the streets and voiced our opposition because it [busing] would have destroyed our stable community.” The call to action was successful. According to an August 6, 1977 Chicago Tribune article, ninety-eight percent of students skipped classes at Bogan and seven elementary schools in the [far] Southwest Side neighborhoods.

At the time, virulent racist protests were happening across many Chicago neighborhoods. In the midst of a local media spectacle, Rev. Jesse Jackson, founder of Operation PUSH, personally escorted a group of Black students from a severely overcrowded Barton in the Auburn Gresham community to Stevenson. Jackson was heckled and spat on by white supremacists, including a group of white mothers dubbed the “Bogan Broads,” who led militant anti-busing actions across the far Southwest Side.

In 1965, civil rights advocates in Chicago filed a complaint with the U.S. Office of Education arguing that the Chicago Board of Education violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Delmont wrote that activists argued that the Board had deliberately segregated the city’s public school system. The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) briefly withheld $30 million in federal funds for probable noncompliance. But after facing backlash from Mayor Richard J. Daley, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and other elected officials, HEW withdrew the case, quickly “exposing the limits of federal authority in the face of school segregation in the North.”

On August 5, 1966, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. organized a march in the Marquette Park neighborhood, three miles north of Scottsdale, to demand that properties be accessible to everyone regardless of their race. In a now-famous photograph, King fell on his knee as a mob of seven hundred white protestors hurled rocks that hit him on the head. King told the Tribune, “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen—even in Mississippi and Alabama—mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’ve seen here in Chicago.”

Marlene Buckner, whose eight- and six-year-old daughters, Toyia and Michelle, would be part of the voluntary busing plan, alluded to this widespread hostility nine years later in 1977, when she described the anti-busing protests: “down South, Blacks and whites are going to school in peace. Here we are so backward, we are fighting a 1950 and 1960 issue. And Chicago is supposed to be liberal.”

Dionne Danns explains in her recently published book, Crossing Segregated Boundaries: Remembering Chicago School Desegregation, that “anti-busing boycotts symbolized the desire to maintain segregation and reaffirm racial boundaries” and they regarded “busing as a symbolic affront to their desires to keep Blacks out of their neighborhoods.”

Chicago’s busing plan would “permit pupils in fifteen severely overcrowded elementary schools to transfer to 51 schools with space. Five of the fifty-one schools eligible to receive children are in the Bogan [Scottsdale and Ashburn] area,” according to a June 1977 Tribune article. The plan was also described as a “permissive transfer” program that, in addition to relieving overcrowding, would increase racial integration in receiving schools. In a later Tribune article, Mrs. Buckner is quoted saying: “Blacks have fought too hard for rights to give them up without a fight … we must stop accepting the worst for our children.”

Later during an August 5, 1977 BCC meeting, members of the council voted to boycott the first day of school and every Friday if the Board of Education persisted in its integration plans. Over six hundred people were present in the meeting when community resident Ann Frank told the audience they “will not accept any desegregation plans.” At stake for these parents was the placement of “270 students from two all-Black schools, Raster and Barton, to transfer into six Bogan [Scottsdale and Ashburn] area elementary schools.”

Support independent, context-driven regional writing.

By the time of the August meeting only seven Black students had signed up for the program. Betty Barlow, another community member exclaimed, “That’s seven too many. It would establish a precedent.” White parents on the far Southwest Side had been successful at fighting various student transfer plans since 1963. Their pressure was showing some success when Supt. Hannon indicated to the Tribune that was willing “to back down on a proposal to place all-white Bogan in a predominantly Black administrative district.”

Rev. Jackson stood with parents of bused children and told members of the press that he pressured Governor Thompson to send letters to parents of students who would be bused that local governmental agencies would provide safety for their children. On August 25, 1977, city and school officials announced the “formation of a task force of school, police, and city agencies who will work to insure the safety of bused children.” Jackson later said at the press conference that “there are many white persons who live in that [Bogan] area who are not subject to demagoguery.”

Pat Johnson, president of District 20 community council, a predominantly Black student school district on the South Side, told the Tribune on August 26 that her daughter’s school, Barton, was severely overcrowded, with sixty students in one classroom with two teachers. She originally didn’t intend to have her daughter participate in the busing program to Stevenson, but after seeing all the demonstrations against it, she said, “there must be something good in those schools if they don’t want us in it.”

Even a prominent white leader in Ashburn-area school affairs wanted to remain anonymous when she spoke to the Tribune on August 28 because she feared “getting a brick through [her] front window.” She drew a map of segregationist views by neighborhood when she described that to the east of Pulaski Road along 79th Street, roughly in the Wrightwood and Ashburn neighborhood, are the “agitators” who “are getting all the publicity for their protests against school integration” and to the west in the Scottsdale neighborhood are the “passive people who prefer to ‘mind [their] own’ business and to refrain from any militant action.”

She also identified the women who led the anti-integration protests, mostly white women in their 40s and 50s who have sons and daughters attending Bogan. In one of their school affairs meetings with Supt. Hannon, they asked for a three-year moratorium on busing because it would “permit the selling of property for some people before Blacks [came] into the area schools” and because Black students have a “different culture … a different lifestyle” and would not be “able to maintain the standards of education” for white children. The anonymous person confirmed Johnson’s worries about the safety of Black children being bused in, saying, “If I were Black, I would think twice about sending my child here [Scottsdale]. I think their fears are very genuine.”

A week before the first day of school, the Parent-Teacher Associations of Bogan, Stevenson, and Hancock (now a middle school extension of Stevenson) wrote a letter authorized by Bogan PTA president Joan Nykel to Supt. Hannon, asking for “assurances their children will be protected from harassment or physical attacks” and the concern of “potential intimidation of whites against other white students” in the first week of classes.

All three of the PTAs were worried about white on white violence, as they “feared their children would be harassed or injured, not by Blacks, but by other whites in the Bogan area.” Nancy Ragaikis, president of the Hancock PTA, was also concerned that police presence would lead to an impact on the student’s learning environment, and told the Tribune “we certainly don’t want a police state.” She also pointed out the “lawlessness and illegality of the [anti-integration] boycott” endorsed by the BCC.

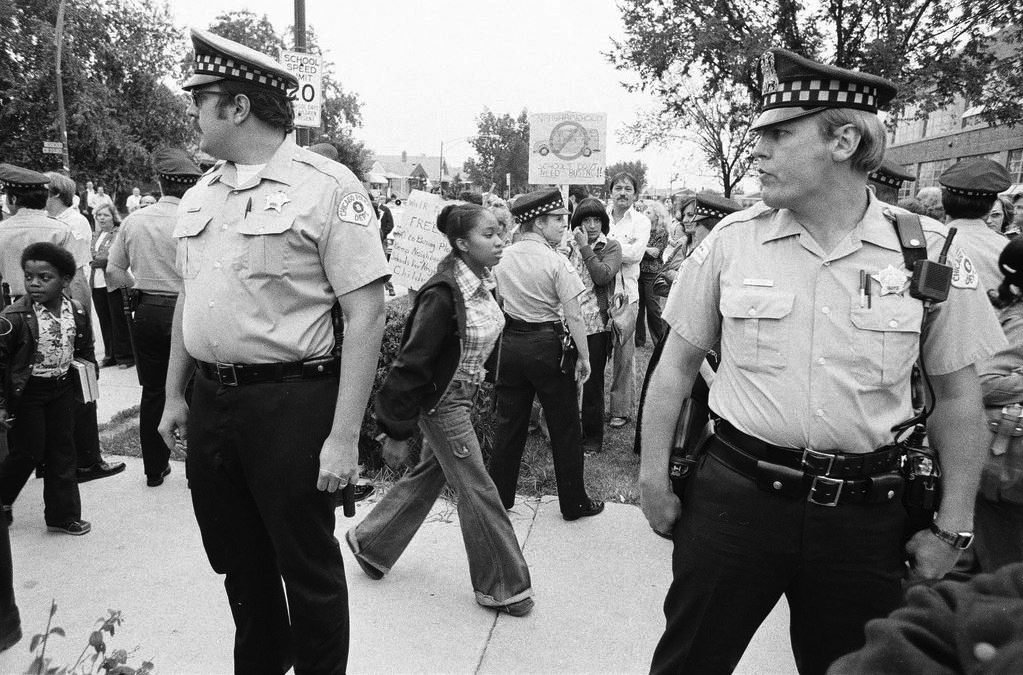

After a hot summer of boycotts, threats, and negotiations, the time to integrate and reduce overcrowding in public schools had finally arrived. September 7, 1977, was the first day of classes for Chicago Public Schools students and the Board of Education issued “433 press badges to reporters, photographers, and television technicians” for a media spectacle that reached local and national news outlets. The Washington Post reported that “inspired by weeks of impassioned hyperbole on the television screens and by daily front-page treatment in the city’s competitive newspapers, the early-rising reporters descended like an army on the three-square-mile Bogan High School area for the opening of school.”

Photo credit: Chicago Sun-Times

Four hundred and ninety six—less than thirty percent of eligible students—were bused to schools throughout the city that day. Although Supt. Hannon declared the first day of school as a “grand beginning” and the Tribune’s front page headline was “School busing passes test,” it certainly was nowhere near a success story for Black students.

Following a prayer breakfast organized by Operation PUSH, Jackson escorted a few children from Barton in his car, followed by a CTA bus that was led and trailed by several Chicago police squad cars and carried twenty-seven Black students and one white student from Byford Elementary (it has since been demolished; Brunson Math & Science Specialty school occupies the former site) to Stevenson.

The Black students were greeted by white supremacists picketing in front of the school near the intersection of 80th and Kostner Avenue. Dozens of riot officers and policemen lined the street, preventing the agitators from blocking the road. Twenty-four-year-old Robert Lang, from Niles, was arrested for heckling and spitting in the direction of Jackson as he and the students descended from the bus. Pictures from the Chicago Sun-Times show adults and teens holding signs that read, “Give them bananas, not our schools,” “Official Bogan Bigot,” “They’ve take our rights, they’ve broken our rules, they’ve ruined our neighborhood, and they’ll ruin our schools,” “Italians Hate N******, Polish Hate N******, Irish Hate N******”. Some protesters placed an effigy of a person with a black bag over its head and bananas tied to its wrists atop a No Parking sign.

Parents carried out their promises of boycott by keeping one hundred and fifty of the 613 pupils registered home from school that day. Shortly after noon, a bomb threat was reported at Stevenson, but police found nothing after searching the building. In a true gaslight moment, Chicago Mayor Michael Bilandic told reporters “the most important thing is what happened today—an uneventful opening.”

By the end of the first week of school, protestors had marched to the Stevenson branch after being threatened with arrest by the 8th District police commander due to their picket line outside Stevenson. Imitating tactics from Black freedom fighters, twenty-two people blocked the eastbound intersection of 79th and Kostner. Some had the word “resist” written on their arms and foreheads, others yelled at police: “We are on our property. We paid for it with our taxes.” The police continued to give orders of dispersal but made no arrests.

Torches illuminated the sky, and hundreds of people sang patriotic songs and chanted racist taunts as they marched down commercial streets in a “torchlight parade” organized by the Bogan Community Council on the Sunday before the second week of school. About a thousand people attended this quintessential expression of white supremacy, which ended with eleven people being arrested. Among them was Joyce Winter, one of the leaders of the Ashburn Civic Association. Organizers hung and burned effigies of Supt. Hannon, state school superintendent Joseph M. Cronin, and Edward A. Welling Jr., the school board’s desegregation project manager. Additionally, four people were seriously injured when two Black drivers drove into crowds of protestors as they attempted to flee the rock pelts.

On the second Monday, Black children continued to be terrorized by white adults and teenagers as they exited Stevenson. Taunts such as “N***** go home!,” “We don’t want to integrate,” and “I wish I were an Alabama trooper”—in reference to the May 1963 incidents of police brutality in Birmingham toward Black families participating in MLKs business boycott—were shouted at the Black pupils as they boarded the bus to go back home.

Six police officers had to guard the school bus and wait for reinforcements as a mob of sixty people prevented the bus from leaving. The New York Times featured a picture of a mother, Mary DeLuca, being arrested for disorderly conduct and carried away by Chicago police. She and her daughter, also arrested, lived at 80th and Kilpatrick, half a mile away from the elementary school. In the evening, two boys aged thirteen and fourteen were named in a juvenile petition for mob action along with six adults taken into custody for injuring a Black family in a car and damaging six other cars of Black drivers with rocks and objects along 79th Street. Two of the seventeen-year-olds taken into custody that day would be around sixty today.

The apex of white supremacist violence came on the second Tuesday. Outside Bogan five hundred students held the largest protest against school integration. About three hundred students were threatened with suspension from Bogan for walking out of school, according to the NY Times, some of whom threw rocks and harmful objects at cars on 79th Street; another thirty-three students were arrested for inciting other students to join them in pelting rocks at police officers. Chicago police superintendent James Rochford told the press that “young thugs and hoodlums are about to take over our streets …we are going to be reasonable, but we are not going to tolerate law breakers.” Rochford allegedly also said the violent demonstrations are “the expressions of young people” and accused the media for “distorting all the issues.”

Photo credit: Chicago Sun-Times

Joe and Helen Turner never imagined that once their daughter stepped inside the school bus with her brother Marvin it would be the last time they saw her alive. Mellaine Turner, a seven-year-old Black student participating in the Stevenson busing program became a victim of racial terror. “Go back, go back, go back where you belong!” dozens of white kids shouted as a bus carrying eighty-four Black students arrived at the elementary school. The Tribune omitted the story but both the Freeport Journal-Standard and the Galesburg Register-Mail reported that Mellaine was shaking and crying as she went to the principal’s office with chest pains at 10 a.m. Around 8 p.m. the Wyler Children’s Hospital in Hyde Park pronounced her dead due to an apparent sickle cell crisis.

Dr. Earl Fredrick, a spokesman for the Midwest Association for Sickle Cell Anemia, said at the time that if a child is “stressed enough, it is possible that such an event [with racial slurs and taunting] could trigger an attack. That it is likely, I wouldn’t want to say.” A cardiologist who asked to remain anonymous said the protest could have “created the atmosphere for the attack. The disease obviously did the rest.” Hellen Turner told Operation PUSH that her daughter’s last words were, “Go back, go back, go back.” Jackson and his team called for a news conference. As word of Mellaine’s death got back to Scottsdale, youth and adult segregationists chanted “Hooray for sickle cell!”

Forty-four years later as I retrace the bus ride from Barton to Stevenson in my car, I look to see if there are any historical markers or plaques commemorating the success of civil rights activists at integrating Stevenson or Bogan, or even an honorary street sign for Mellaine Turner. Nothing. From third to eighth grade, I walked through the same doors at Stevenson as those brave children. Never once did any teacher or administrator teach us about the historical significance Scottsdale had in the national struggle to integrate schools. Whether the omission is intentional or not, it is time that this history be recognized, so that current and future generations may learn from it. The fight to desegregate was not only fought in the distant deep South but was a struggle nationwide, including in our very own Chicago neighborhoods. ■

Ismael Cuevas is the lead advisor for archival and historical research for the upcoming documentary SOUTHEAST: a city within a city. Ish was raised in Scottsdale but now resides in the Pilsen neighborhood. He studied Latinx history at UT-Austin and political science at UW-Madison. This is his first piece for the Weekly.

Cover image credit: Chicago Sun-Times.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.