By Kim Kankiewicz

When contemporary pundits talk about restoring the vitality of America’s industrial cities, they rarely mention choral music. Macroeconomics, attracting jobs and tech, tax subsidies and infrastructure, sure. But not singing societies. But for Gilded Age thought leaders, choral music societies ranked alongside chambers of commerce as essential civic institutions.

Civic-minded Victorians upheld music as a harmonizing influence in teeming, polyglot nineteenth-century cities and promoted choral singing as a form of music accessible to amateurs from all walks of life. New York Tribune editorialist Henry Krehbiel, who began his career as a music critic in Cincinnati, spoke for many when he claimed in 1887 that “a more general, more zealous, wiser cultivation of choral music is the greatest of the socio-educational needs of the United States.”

Behind such fervent endorsements, choral music societies appeared in practically every town with a population of more than a thousand. A city’s amateur choruses were a source of pride, write John Ogasapian and N. Lee Orr in Music of the Gilded Age. Choirs voiced “some of the strongest elements of Victorian culture: the strong sense of duty, community participation, broad religious sentiment, rising nationalism, and enthusiasm for the new romantic music styles.”

While community-based mixed choruses came into their own during this period, men’s choruses predominated in the industrial Midwest. Chicago alone boasted more than 60 men’s singing societies in 1885. Many of these groups, like many male choruses throughout the region, were formed by German immigrants perpetuating the männerchor tradition of their homeland.

Attitudes toward paid labor further supported the proliferation of men’s choirs. Choral singing was deemed an edifying alternative to other leisure activities, and a mollifier of would-be union agitators. Addressing the general assembly of the National Education Association in 1900, music educator Arnold J. Gantvoort argued that “the more prosaic and sordid a man’s life and daily occupation,” the more he needed the ameliorating effects of music. Gantvoort added: “We believe that when the genius of song crowns the gospel of work there will be fewer strikes, the grimy faces will be less haggard, the tense muscles will lose their rigidity [and] labor will be more faithfully, more cheerfully performed.”

Men’s singing societies, and the notion that groups of men singing together would soothe proletarian discontent, might seem like quaint relics of a bygone era, if it weren’t for the endurance of several historic male choruses still performing in Rust Belt cities. Take away the barrel-chested condescension of commentators like Gantvoort, and members of today’s male choruses might hear some true notes in Gilded Age observations about the benefits of choral singing. Contemporary choristers are likely familiar with an organization called Chorus America and its Chorus Impact Study, which found that choral singers engage in civic and philanthropic activities at significantly higher levels than members of the general public.

“If you’re searching for a group of talented, engaged, and generous community members, you would do well to start with a chorus,” writes Chorus America Chairman Todd Estabrook. “It would be a mistake not to leverage the benefits that choruses bring to … the communities they serve.”

Kristin Puch, director of Research and Advancement at Cleveland’s Community Partnership for Arts and Culture, points out that choral music organizations contribute to the economy by creating jobs and bolster communities by enriching the cultural landscape.

“The quality of life they create can help brand Rust Belt communities as interesting and unique places while strengthening the social fabric of communities engaged in their events,” Puch says.

Historic male choruses have played an integral, if underappreciated, role in Rust Belt culture for decades. These choruses—including classically oriented groups, German-language choirs, and groups that began as glee clubs sponsored by industrial employers—are unsung contributors to their communities’ vitality.

Ecce Quam Bonum

When Mike Haase describes his “great concern” over dwindling head counts and the under-representation of young people, he could be talking about the population of many Rust Belt cities. But Haase is speaking as president and archivist of the Singers’ Club of Cleveland, a men’s chorus that presented its first public concert in 1892 and, according to its website, is the city’s oldest continuously performing music group.

Like other historic men’s choirs in the Rust Belt, the Singers’ Club has expanded and contracted in tandem with its community. The group began as a YMCA program and featured 29 members who sang at church services. Intent on building a first-rate men’s chorus representing a cross-section of Cleveland, director Carroll Ellinwood and composer Homer Hatch undertook an ambitious recruitment campaign in 1893.

A newspaper clipping from the club’s archive announces what sounds like a Victorian-era American Idol audition without the possibility of fame, inviting male singers with “musicianship of more than average” to participate in “a stiff vocal examination by a committee of well-known musicians.”

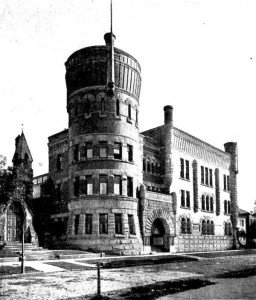

The recruitment appeals were effective. As Cleveland’s population exploded from 380,000 in 1900 to nearly 800,000 in 1920, the Singers’ Club grew rapidly as well. The club featured more than 100 singers in 1910 and more than 150 singers by the mid-1920s. The choir—and an impressive roster of guest artists like film star Nelson Eddy, bandleader Fred Waring, and Italian tenor Tito Schipa—routinely sold out concerts at Grays Armory in downtown Cleveland, with standing-room audiences of 2,500 ticketholders. One concert was delayed by an hour while stage managers rigged an outdoor speaker system for an overflow crowd of a thousand.

True to its founders’ democratic mission, the Singers’ Club embraced members of varied ethnicity and economic status. According to Cleveland historian William Ganson Rose, the Singers’ Club included “millionaires, mechanics, and professional men.”

Luke Case, a Singers’ Club member since 1957, says the club has always been about more than music.

“These are not guys that you just go sing with and stand up and say, ‘Well, that was a good rehearsal. Now I’ll go make widgets and you go paint buildings,’” Case says. “You get to be pretty good friends with people.”

Eight-year member Mike Haase agrees. “There is a degree of camaraderie within the organization that I haven’t seen in other organizations,” he says. “The Singers’ Club is a big component of a lot of people’s lives, and friendships develop over the years.”

Both Case and Haase mention an upcoming memorial service for a former Singers’ Club member.

“We will sing at the service, and we take that quite seriously,” Case says. “And there will be more than one tear shed while we’re doing it.”

Far from competing with the task of making music, Case and Haase believe camaraderie enhances the group’s musicianship. Case recalls a social pressure that kept members accountable in his early days with the Singers’ Club.

“I mean this was a religion. If you missed a rehearsal, you were really made to feel like a schlemiel,” he says. “Times have changed now. It is no longer considered an act of treachery to miss a concert.”

Nowadays, the relationship between amity and artistry is exemplified by a song sung in Latin at the start of every Singers’ Club rehearsal or concert: Ecce quam bonum quam que jucundum habitare fratres in unum. Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell in unity. (A snippet of the Singers’ Club performing “Ecce quam bonum…” is embedded below.)

“When I went to my first rehearsal and they started off like that,” Haase says, “I was just blown away at the musical quality of these guys singing the song. And from the day I walked in the door, I said, ‘I want to be part of this group.’”

Indeed, the sound of men singing together is what attracts many members and keeps them involved in male choruses. Case refers to a “range of expression” and Haase a “tonal quality” unique to male choirs. Jameson Marvin, Emeritus Director of Choral Activities at Harvard, has an explanation for this distinctive sound. Marvin’s 32-year career at Harvard included directing the University’s Glee Club, one of the nation’s premier male choruses.

“When you have this rich sound that is not just a huge, loud, low sound, but one that has a fair amount of clarity, then you have the opportunity to experience overtones flying above the men’s chorus,” Marvin says. “You create this whole overtone series in the air. It takes a while to hear it, but it’s so beautiful.” Marvin believes that while audiences, and even singers, might not be conscious of the overtones, their presence is part of the appeal of male choral singing.

Along with the sound, Case says he enjoys the repertoire available to men’s choruses.

“A lot of literature can be cross-sung, but there are pieces that just don’t cross,” Case says. “A solid drinking song just isn’t the same. Or a mixed chorus singing, ‘Come all you boys from the river and listen to me for a while, and I will relate you the story of my good friend Johnny Stiles.’”

The wealth of choral literature for male voices, and the fact that much of this music fell out of use when men’s colleges went co-ed and phased out their glee clubs, inspired the creation of the National Library of Men’s Choral Music in Washington, D.C. A project of the Washington Men’s Camerata with support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the library seeks to preserve works that have gone out of print and to serve the choral community by lending music scores to men’s choirs across the nation.

“People have been very supportive of the library,” says Frank Albinder, who directs the Washington Men’s Camerata and other men’s choruses and serves as president of Intercollegiate Men’s Choruses. Albinder adds that digitizing the library’s collection is a long-term goal. “With the rapidly changing world of music publishing, I’m not sure how long they’ll continue to release paper scores,” he says. “Pretty soon, everything will be a PDF and we’ll all be holding iPads.”

The digital age is impacting choral music in other ways as well. Mike Haase believes internet access increases the already intense competition for the public’s attention.

“Flip a switch and you’ve got 3,000 different choices of music,” Haase says. “Having to go and search it out—you don’t have to do that anymore. It comes to your door.”

On the other hand, Haase points out, a sense of digital overload makes the case for choir participation more compelling.

“Electronic communications tend to take the human component out of interactions,” Haase says. “That’s one of the big potential draws, I think, of our organization. Not only do we make fine men’s choral music, but we also have a relationship with other members of the club that is not common.”

Haase says the Singers’ Club will incorporate this message into a recruitment campaign designed to attract younger members and increase the club’s ethnic diversity. Currently, more than half of the 60 members are past retirement age. While the club generally has a handful of African-American, Asian, or Hispanic members, they are aiming for an ethnic mix that more closely resembles the diversity of Cleveland as a whole.

The club’s leadership acknowledges that joining a choir is a tough sell for men who are already balancing schedules that tend to be fuller and less predictable than they were a half-century ago. Haase himself was initially invited to audition for the Singers’ Club in the 1980s and declined due to other commitments. Since he joined in 2006, his membership has afforded him unexpected opportunities for community engagement through performances at civic assemblies, industry gatherings, and sporting events.

“I’m sort of kicking myself that I didn’t get involved with it 20 years earlier,” he says. “Participating in these other activities around the city, you get to learn a lot of things that you really wouldn’t have any exposure to otherwise.”

Ich kenne ein Land

“That evening at the Cleveland Theater, we gathered on stage in front of a grand statue of Freedom created for the occasion. As 400 male voices lifted in harmony, my entire being was seized by a deep longing for my homeland. How proud my parents would be if they could be here tonight. I sang for my uncles and aunts in the large audience, for my parents and brother back in the Old Country, for the traditions that held us together.”

These are the words of Michael Harm, narrator of Cleveland native Claire Gebben’s historical novel, The Last of the Blacksmiths. Based on Gebben’s real-life ancestor who arrived in Cleveland from Germany in 1857, Harm sang in one of the hundreds of German men’s choruses that proliferated throughout the industrial Midwest in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Music scholar Suzanne Snyder has documented more than 900 German-American singing societies that existed at one time in the United States, most of them men’s choirs modeled after singing clubs formed in Germany for political and social reasons. The American groups served as bridges between old and new worlds, preserving ethnic traditions while shaping the culture of industrial age cities. By 1893, when Cleveland hosted a German-language Sängerfest, or song festival, comprised of 2,200 singers from 85 Midwestern choirs, such festivals were attracting audiences of more than 10 thousand.

President William H. Taft acknowledged the cultural contribution of German singing societies at the Philadelphia Sängerfest in 1912, where a “select” choir of 6,000 men greeted his arrival with a chorus of the national anthem.

“The pursuit of art by the many,…under conditions in which good comradeship is made the chief incident, is the custom that we have borrowed,” Taft addressed his German-American audience. “Such associations as this…have educated the public at large and, what is even more important, have widened the means of making happiness.”

Taft’s comments were not empty pomp. German-American singing societies popularized the works of composers like Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Liszt in the United States. Audiences heard the poetry of Schiller, Goethe, and Heine set to music. Yet, as noted in Music of the Gilded Age, German choruses comfortably straddled the line between high-culture and vernacular. The program from the 1893 Cleveland Sängerfest—which, at 101 pages, is a history book unto itself—acknowledges:

Taft’s comments were not empty pomp. German-American singing societies popularized the works of composers like Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Liszt in the United States. Audiences heard the poetry of Schiller, Goethe, and Heine set to music. Yet, as noted in Music of the Gilded Age, German choruses comfortably straddled the line between high-culture and vernacular. The program from the 1893 Cleveland Sängerfest—which, at 101 pages, is a history book unto itself—acknowledges:

Of all the numbers on the programme the Volkslieder (Folks’ Songs) invariably please the most. In the first place, the singers prefer them, (because they require less study), secondly, because the sound effects of a grand chorus in sustained, not polyphonic works, are brought out better, and thirdly, the audience recognizes dear old friends in them, and as it requires no exertion to follow the music, the enjoyment is the greater.

Participation in German-American singing societies declined sharply during the First and Second World Wars, when anti-German sentiment brought these groups under scrutiny. The Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund (North American Singers Association), which has organized national Sängerfests since 1849, held no festival between 1914 and 1924. In 1944, the Sängerbund was declared an “unpatriotic organization” and temporarily lost its nonprofit status.

Membership in German men’s singing societies increased again after both World Wars, as choruses reconvened and German immigrants arrived in new waves to U.S. cities. Jeff Watter is a member and secretary of the Milwaukee Liederkranz, one of the few German-American men’s choirs whose activities were not disrupted by war. Watter sings with several German-born men in their seventies and eighties who joined the Liederkranz upon immigrating to Milwaukee after WWII.

“This was a means of talking German, getting to know people,” Watter says. “It was comforting, you know, the folk songs of the homeland.”

Songs of the homeland were prominent at the Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund’s 2013 Sängerfest, which featured music from each of Germany’s sixteen states. “Ich kenne ein land”—“I know a land”—the anthem of the state of Hesse, was among the songs performed by all-male voices. “There as a child at mother’s hand, I sat in blossoms and flowers,” the English translation reminisces. “I salute you my homeland, you marvelous land!”

Jeff Watter, who attended the 2013 Sängerfest with the Milwaukee Liederkranz, says a basic understanding of German language enhances the performance of such songs.

“When I sing it, and I try to extrapolate the English translation in the German language, it’s just really beautiful,” he says. “They’re always singing about the Heimat—Heimat means homeland. And even though I’ve never been to Germany myself, there’s a certain sort of resonance in German song. It brings back a memory I never had.”

Much as nineteenth-century German immigrants joined men’s choruses to preserve a connection to the land they had left behind, Watter joined the Milwaukee Liederkranz ten years ago to connect with the culture of his German ancestors. Growing up as a Baby Boomer, when Watter’s exposure to German culture came largely through negative depictions in war movies, he felt ashamed to be “100 percent German.” In his mid-forties, he attended a citywide German chorus rehearsal and was surprised to sense an immediate affinity with the group.

“All through middle school and high school, I carried a briefcase. And nobody I knew carried a briefcase. It was just not cool,” Watter says. “I walked into the practice, and I was astounded to see a room full of people, many of whom had briefcases. And I thought, I’m home.”

Watter credits the Liederkranz with expanding his sense of self. “I’ve developed a much stronger identification with my German roots,” he says. “I see myself as German now, whereas, as a younger person, I didn’t see that in myself.” Watter has embraced his German identity so fully that his granddaughter calls him “Opa,” German for grandpa.

The Milwaukee Liederkranz, which has a current membership of about 40 singers, has grown in recent years from a low of about 30 members. Watter attributes this growth to the aging of the Baby Boom generation.

“This isn’t something you do when you’re 20,” he says. “It’s something you do when you reach the point in your life when you’re getting in touch with your heritage. So I think there’s going to be a certain influx of Baby Boomers once they get into their older years.”

Still, Watter notes, participation in German singing societies has diminished significantly since the mid-twentieth century, when the Milwaukee Liederkranz had as many as a hundred members. Audiences are much smaller as well, in an era when the populace and its President are more likely to attend a Beyoncé concert than a Sängerfest.

“Now people have so many more options, ways to spend their time,” Watter says. “There are not a lot of people who say, dang, let’s go to a choral concert. I think to a certain extent we’re singing for our own pleasure.”

Friendship, Fellowship, and Song

Friendship, Fellowship, and Song

Far from singing mostly for themselves, twentieth-century employee glee clubs sang as representatives of their industrial employers. By the late 1930s, nearly every large manufacturing company had an employee choir, many of them men’s glee clubs.

“I think the fact that most employees were male can’t be ignored,” says Charles Bash, a 35-year member of a choir that was founded in 1936 as the Dow Male Chorus at Dow Chemical Company in Midland, Michigan. While the Dow Male Chorus began as a small group of men gathered around the piano after a church service, other industrial choruses started as intentional efforts to engage employees in song.

The Gentlemen Songsters began singing in 1932 as the Chevrolet Glee Club of Detroit. According to the group’s website, the glee club was founded by a general foreman at Chevrolet who believed men needed to be part of something more than work. And, as a former Gentlemen Songsters director used to say at the start of each concert, the men’s wives appreciated knowing “where they were every Tuesday night.”

The Dow Male Chorus and the Chevrolet Glee Club are among the many former employee choruses that spun off as independent organizations when industrial employers stopped sponsoring choirs beginning in the 1960s. The eleven member choruses of the Great Lakes Male Chorus Association, for example, represent eight former employee choirs: the Dow Male Chorus, two Chevrolet Glee Clubs, the REO Motor Car Company Glee Club, the Studebaker Male Chorus, the Bendix Male Chorus, the Tyler Refrigeration Blue Notes, and the Buick Male Chorus. (Not beholden to stockholders, the Detroit Post Office launched a men’s chorus in the 1960s, just as private industry was moving away from choir sponsorship. The Detroit Post Office Male Chorus survived until at least 1978, recording an LP and appearing in a production of the opera Faust.)

From a current perspective, with arts organizations appealing to economic-impact studies to justify their existence, it’s hard to imagine businesses paying a choir director’s salary and underwriting a choral group’s performance costs. But Charles Bash says that’s just what happened at Dow Chemical Company and other companies with employee choirs. On two occasions, Dow even funded performance tours, one across Michigan and one to Dow facilities in Oklahoma and Texas.

Perhaps the eagerness of manufacturing companies to sponsor employee choruses reflects the persistence of the attitudes expressed by Arnold J. Gantvoort at the National Education Association assembly. Perhaps employers believed workers who sang together were less likely to strike together. More likely, though, the prevalence of such choirs reveals as much about audiences as employers. When choral music concerts were heavily attended, an employee choir was effective marketing, its members functioning as goodwill ambassadors wherever they sang.

Now the majority of employee choruses have gone the way of the Dow Male Chorus, which lost its company sponsorship in 1961 and became an independent organization (still going strong) called the Men of Music. But Charles Bash explains that by establishing both a choir and an orchestra, Dow fostered a community of music that continues to thrive in the Midland area. In the 1970s, private foundations raised funds to construct the Midland Center for the Arts, a building that houses rehearsal rooms, lecture halls, art studios, and two performance venues.

“Without the model of the Dow Male Chorus and the Dow orchestra,” says Bash. “I do not believe this would have happened.”

The legacy of employee choruses is evident at an annual concert called Industry Sings, where choirs established by Ford, Chrysler, General Motors, and Detroit Edison have performed together since 1957. It is evident in a new event called CincySings, a Glee-style competition among singing teams from Cincinnati businesses. And it is evident in the Great Lakes Male Chorus Association, where many singers are still connected to their original employee sponsors.

The Great Lakes Male Chorus Association’s anthem, composed by Men of Music conductor Grace Marra, evokes nostalgia for a fading tradition: “We join together brothers all |To raise our voices and recall | Our friendship, fellowship, and song.”

Members of historic male choruses express concern over declining participation—and it’s unlikely that choral music will ever reach the level of popularity it achieved more than a century ago. Yet there is reason to believe the genre is poised for resurgence. Chorus America reports that choral music participation is increasing overall. In 2009, 18.1 percent of U.S. households had one or more adults singing in a choir, compared to 15.6 percent in 2003. Nationwide, the total number of adult choir members rose from 23.5 million in 2003 to 32.5 million in 2009. Surveys indicate that more Americans participate in choral singing than in any other performing art.

Jameson Marvin, who has remained active in the Intercollegiate Men’s Choruses (IMC) organization since retiring from Harvard, has seen an increase in men’s choral singing at the college level in particular. At schools where glee clubs long ago went co-ed, new men’s choruses have cropped up alongside mixed and women’s choruses. IMC’s membership has swelled in recent years. The IMC website lists 89 member choruses, up from 47 in 2008. Marvin believes more men singing at the college level will translate to more men singing in community choirs, as graduates seek to continue their college experience.

The renewed popularity of barbershop singing and the relatively recent establishment of gay men’s choirs in many cities are more good news for choral music. While these newer groups fill different niches, they are contributing to the general enjoyment of this rich genre within communities.

“As one who has grown up in this tradition, I can only say that the friendships engendered and the benefits derived … are too precious and enduring to cast aside,” said former Yale Glee Club director Fenno Heath in 1968, when the future of male choral singing looked uncertain. Today’s historic men’s choirs have sustained the tradition Heath described, cultivating a landscape where newer male choruses can thrive as well. Together, their voices are singing hard-working cities into the next era.

Kim Kankiewicz is a writer, educator, and communications professional living in the Seattle area.

Great, comprehensive article. I attended the Saengerfest in 2013 in Milwaukee, and many district Sangerfests over the last 25 years, as a member of the Damenchor in Evansville, Indiana. It is truly a memorable experience to join a thousand or so others, singing together.