In Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek Valley, the messy legacy of the country’s first petroleum boom

By Jake Maynard

If you spend enough time driving around Pennsylvania, the place names start to develop thematic relationships. There’s Blue Ball, near Intercourse. There’s Burnt Cabins, near Fort Littleton. Shmokin, near Pottsville. Pigeon, near Owl’s Nest. And, in the western part of the state, seventy miles north of Pittsburgh, there’s a forty-six-mile stream called Oil Creek, which flows into the Allegheny in Oil City, six miles from Oleopolis. The region surround Oil Creek was once called Oildom, or Petrolia. Above and below the land lay, a hundred and sixty years later, the remnants of the world’s first oil boom. As a kid, I took some pride in that. Not Texas or California, but us.

Now, I was headed to see an empty field called Pithole City, where a boomtown sprung up and collapsed, fast as a fungus, in the heat of boom. Shops and doctors’ offices, hotels and a thousand-seat theater were erected in the type of frenzied optimism that can only come from money flowing from the Earth. The population would swell from zero almost twenty thousand within a year. And now, back to zero.

Western Pennsylvania looks a lot like McKean County, where I grew up. The hills shrink and the woods give way to more fields, but it’s the same chlorophyl palette of summer. The same Trump flags whimpering in the humidity. The same white boys on four-wheelers, ripping across their lawns. And, if you look closely, you’ll see the same disused oil and gas paraphernalia hidden in the woods. You’ll find pipes and stone foundations and sometimes uncapped wells or storage tanks. I don’t find it ugly, but the contrast it strange. Some spots still look primeval. Others look raw and tender, like a bruise.

“Rural Pennsylvania doesn’t fascinate the world, not generally,” writes Jennifer Haigh in her fracking novel Heat and Light. “But cyclically, periodically, its innards are of interest. Bore it, strip it, set it on fire, a burnt offering to the collective need.” The story of Pennsylvania oil works the same way. Pithole, home of the world’s first oil pipeline, made the rounds in the news during the Standing Rock protests. Oil heritage is always a common talking point during the debates about fracking, which has failed to bring much of the promised prosperity to local communities. Ted Cruz summed it up in a 2016 rally: “Pennsylvania is an energy state.”

Pithole, Pennsylvania circa 1870. Public domain image via Wikimedia.

I knew not to expect the type of ghost town embedded in the American psyche: old saloons with doors creaking in the wind. Oil men were too resourceful for that. When oil was struck a few miles from Pithole, the buildings that hadn’t burned were disassembled and moved, leaving just empty sockets in the land. But still, I’d expected more drama than a sloping field, just broom sedge and goldenrod. It looked more battlefield than ghost town—Gettysburg without all the school kids. When it failed to speak to me, I blamed the heat. But as I passed one interpretative sign after the next, I started to suspect personal failure. I was a fiction writer; imagining things was my trade. I tried closing my eyes, willing the past to life.

I started down the hill on mown paths that loosely gridded the field. They used to be streets. “One of the wonders of the world,” wrote a New York Times reporter in October of 1865. “A city spreading out along its sloping sides, in all directions, hundreds of houses in process of erection. The eternal collision of nail and hammer, the quick, convulsive rasp of saw, and the cheerful chirrup of the plane great you on every side.” The author goes onto describe forges and carpenters’ shops, theatres and churches, and newfound oil millionaires with “bad grammar” who were “unknown to fame till they came swimming into popularity on a sea of oil.”

At the bottom of the hill, I looked up at what was once Holden Street, and something sparked. Pithole had been a “drawing board town,” a blank slate for speculators. Depending on which primary source you’re reading, it was either utopia or a hellhole. And today, it’s the same for oil’s legacy. You can see glory, like some oil historians have done, or you can see grim, unchecked enterprise. Brian Black, an environmental historian who studies the oil boom, would later tell me: “It’s more evocative in its emptiness.”

My evocation at Pithole was about the time as much as the place. It was summer 2020 and oil was again on the brain, to quote the most popular song of the oil boom. Oil money was finally being ousted from major museums. Huge swaths of Australia were on fire and in California, the Golden Gate Bridge was still hot to the touch from a record fire season which NASA blames partly on climate change. A few months later, a blast of winter air from Canada would freeze Texas, bursting pipes and downing the state-owned electric grid. Within hours, Fox News and the rest of the conservative mediasphere would falsely blame renewable energy for the failings of deregulation and natural gas. It felt like a good time to look back at how it all started.

Look sharp, reader, because oil history moves fast. How fast? Cleopatra could travel at about the same speed as Ben Franklin, but a hundred and ten years after the first well started flowing and Armstrong was skipping around the moon.

A cousin to coal, crude oil is basically the fossilized remains of aquatic zooplankton and algae that sank to the bottom of ancient seas around a hundred million years ago. Compressed by pressure and time, sometimes crude would rise through porous rock and settle in pools. In places like the Oil Creek Valley, those pools would seep to the Earth’s surface. For centuries or even millennia, local Indigenous people used the viscous green/black stuff for bug repellant, waterproofing, lighting, and paint. Early colonizers found similar uses, and Brian Black notes that one eighteenth-century travelogue suggested stopping for an oil bath, which supposedly soothed aches and pains.

Petroleum caused problems for farmers and for salt drillers, who extracted salt water with the same basic methods that were used for the first oil wells. One driller, Samuel Kier, had so much oil that he tried almost everything to make use of it. First, Kier hocked crude as a patent medicine, using images of Seneca people as a marketing ploy. Next, he began refining crude into kerosene at a site in downtown Pittsburgh where the U.S. Steel Tower stands today. (Kerosene was an important lamp fuel alternative to whale oil, because we’d killed most of them already.) Petroleum samples made the rounds in scientific circles and soon George Bissell, an attorney based in New York, caught wind of it. He commissioned a study, lured some investors, and leased a tract of land near the town of Titusville along Oil Creek.

This is where my Pennsylvania elementary education kicks in. In school, we were taught the patriotic gospel of extraction: Colonel Edwin Drake drilled the world’s first oil well in 1859. He and other all-knowing men in the oil, coal, timber, and steel industry built our great state. We took fieldtrips to sawmills and oil derricks, and around that time, my classmates stated throwing whole reams of printer paper into the trash to “support the logging industry.” (Their ringleader was the son of a local timber baron.) Back then, I’d imagined Colonel Drake as a military leader, his work as an act of national service. We’d even watched part of an old industry-sponsored film called “Born in Freedom” starring Vincent Price as Drake.

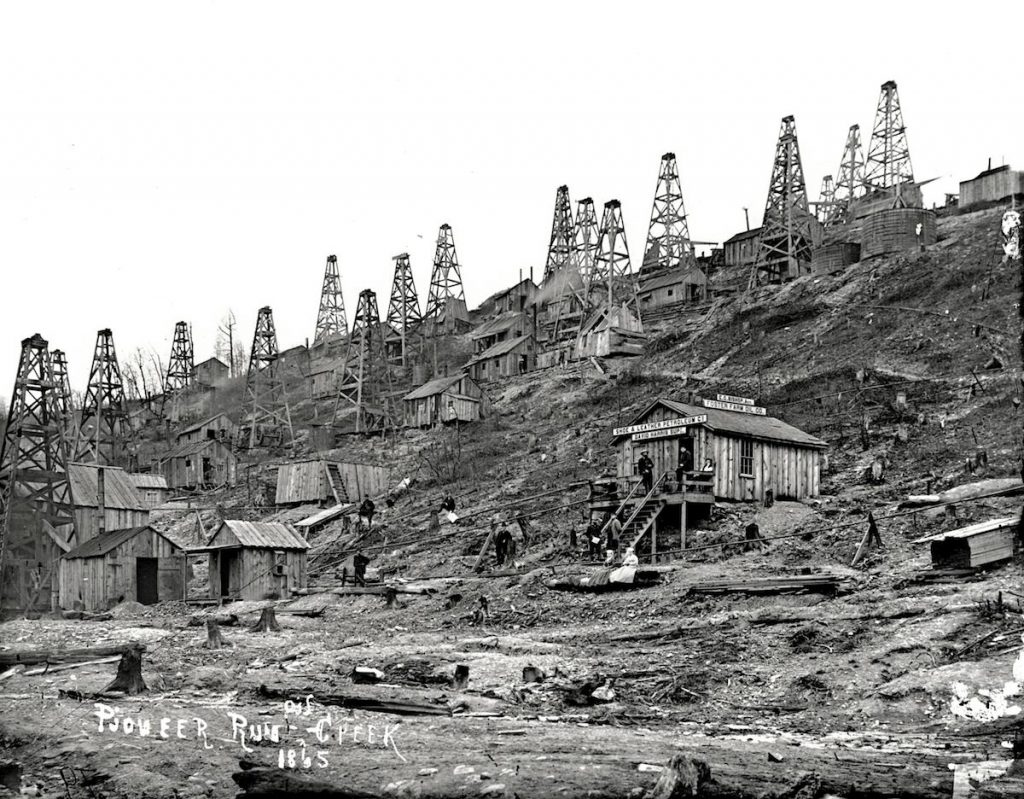

Pioneer Run Creek. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

It turns out that Colonel was just a nickname, developed by The Seneca Oil Company to help Drake build credibility with folks across the Alleghenies. Why they chose him, a sickly thirty-seven-year-old railroad conductor, is still a mystery. According to author Hildegard Dolson, he knew nothing about drilling and had little money to invest. But he was game to take the job for a thousand dollars a year and could make use of a free railroad pass he held. Sarah Goodman, education coordinator at the Drake Well Museum and Park, has studied his correspondence and attributes some of his success to his gift of gab.

The locals thought Drake was ridiculous. They gathered to slap their knees as his first attempts to mine oil failed. He refined his methods and pressed on with the help of a local salt driller named Uncle Billy Smith. His well began showing oil at a depth of sixty-nine feet on Saturday August 27, 1859. When they started pumping the oil out on the following Monday, they had so few barrels that they were filling whale oil jugs, glass bottles, even a washing tub. Kier’s refinery downriver, coupled with extant whale oil infrastructure, meant that the Seneca Oil Company could hit the ground running. But Drake wasn’t built for speed. After securing some barrels and contacting his partners in Connecticut, some sources suggest that Drake took the day off to go fishing. Why not? The mission had been accomplished.

What Drake failed to realize was that he’d launched a whole new enterprise, and with it, new rules. The oil in the ground belonged to whoever could get their hands on it first—Brian Black calls this “the rule of capture”—and to get it, all you needed was a little bit of start-up money and a tiny lease. (If this seems obvious to you, it wasn’t to a mid-nineteenth century thinker. Consider the difference between oil and, say, timber, which belongs to the landholder regardless of whether it’s been harvested.) Drake would have benefitted from seeing the final scene of Paul Thomas Anderson’s petrocinema classic There Will Be Blood: soon, everyone else would drink his milkshake. The pre-industrial, agrarian ethos—work when you need to, fish when times were slow—was finished. Drill Baby, Drill was the mantra of the day. And pretty much every day since.

The swindling commenced at once. Jonah Watson, a prominent local sawyer, took off up the Oil Creek securing lowball leases from farmers who probably hadn’t heard about the strike. Within days, locals were copying Drake’s drilling method, which he’d failed to patent. (After a few shaky investments, Drake would go bust and end up on the dole, eventually receiving an annuity by the state of Pennsylvania for his work in petroleum.) More prominent industrialists, like Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, made fortunes in the valley.

Speculation begot speculation. Wells popped up like dandelions, but many never produced a drop of oil. Prospectors fresh from the California gold rush started showing up in Titusville, whose population would bloom from around three hundred in 1859 to almost nine thousand by 1870. The hillsides were cut bare for the timber, and the erosion led to massive flooding. The creek became an oil highway, trafficked with barrel barges hauling crude to the Allegheny. The water took on a constant sheen, and oily mud covered the land. “The valley,” according to Black, “became more of a process than a place.”

More: The Oil Pipelines Putting the Great Lakes at Risk

That process got some people got very rich. Farmers were suddenly millionaires and fine mansions went up in towns like Titusville, Oil City, and Franklin. Oildom seeped into American cultural life and Eastern newspapers reveled in the contradictions. The Philadelphia Inquirer writes of “majestic mountains” that were “so impregnated with oil in all its forms and odors that it seems almost impossible to exist there for someone uninterested.” A writer for The New York Times describes Titusville with “its muddy streets and high-plank sidewalks, its old-fashioned wooden houses from the lumbering days of poverty and its elegant and costly brick blocks of the oily and wealthy.”

Speculation crawled upland from the valley. By 1865, oil would be discovered near Pithole, in the hills. Prospectors of every sort would stampede the hillside, but most would scatter within a year. The epicenter of American oil migrated up the Allegheny River, settling briefly in McKean County, which in 1881 would produce seventy-seven percent of the world’s oil while also leading the nation in timber production. The boom there would last about as long as Oil Creek’s. (Today, oil and gas still employs about as many people in McKean County as retail, but at better wages.)

If kerosene bested night and day, gasoline came along to obliterate distance. Spindletop, the first great Texas boom, began in 1901 with the bankroll of Pennsylvania investors. Internal combustion was developed concurrently, and by 1903 the Wright brothers tooled over Kittyhawk powered by gas. The Model-T hit the streets in 1908, the same year that geologists discovered a massive deposit of oil in Iran, establishing the company that would be called British Petroleum. (The CIA helped overthrow the government of Iran in 1953 to ensure Western access to that oil.)

You know the rest. Following World War I, energy infrastructure delivered a century of American economic and political power. From fuel to plastics to pesticides to medicine, oil entered every aspect of life.

In the Spring of 2022, the price of gasoline was approaching the federal minimum wage. I fueled up and headed north from Pittsburgh toward Oildom. You know you’re entering the region when the historical markers begin to outnumber the stop signs. If you only paid attention to the markers, you might think nothing has happened along Oil Creek since 1870. There’s the first refinery. There’s the first tanker car. There’s where someone first thought to “torpedo” a well by dropping gunpowder, then nitroglycerin, down it.

And there’s Rouseville, the name a monument to Henry Rouse (1823-1861), who torpedoed a pocket of oil so thoroughly that it coated the surrounding acre of muddy ground. Just as people gathered to gawk, a spark touched it off and burned nineteen people to death. “So numerous were the victims of this fire,” one worker wrote, “and so conspicuous, as they rushed out, enveloped in flame, that it would not be exaggeration to compare them to a rapid succession of shots from an immense Roman candle.” One burn victim staggered to a nearby home, where he was tended to by a woman with a three-year old girl at home. The girl’s name was Ida Tarbell—the muckraker who exposed John D Rockefeller’s shady business practices. She has a historical marker, too.

Rouse may have gotten a town named after himself, but the public history gets increasingly Drakian as you approach the small town of Titusville. There’s a mural of him on a wall downtown and another on the ceiling of a local bank. There’s Drake Street and Drake Well Road, which connects to Museum Road near the Drake Well Museum and Park, administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. It’s right along the creek, at the site of his well.

Holmden Street, in the ghost town of Pithole, once held a jeweler, several hotels and saloons, brothels, banks, and two theatres. Photo by Jake Maynard.

Franklin, writing for Harper’s during the oil boom, described the valley like this: “as unattractive as anyone with a prejudice for cleanliness, a nose for sweet smells, and a taste for the green of country landscapes can well imagine.” But now, after decades of cleanup, things were lush. A snapping turtle was commuting across a lawn from the river to a pond, and a bald eagle flew by, right overtop the painstakingly accurate replica of Drake’s original well. I was there to talk with museum director Sue Bates about the changing legacy of oil, but, eagles aside, things got off to a rocky start. On the patio in front of the museum, volunteers in Drake Well polos were lining up chairs near a podium that fronted the well. Men in suits milled around and someone was fussing with a PA system. I found an older guy volunteering and asked him where I could find Sue.

“She’s with the Ambassador,” he said.

I cocked my head.

“The Azerbaijanis are here.”

My calendar had failed me, and my oil education had too. I learned that the group had traveled from their embassy in D.C. to talk about the world’s first oil well. Their oil well. In 1846, Azerbaijani drillers struck oil at a depth of sixty-one feet just outside of Baku on the Caspian Sea. By the time Drake drilled, Baku was already producing kerosene from underground crude. Dmitry Mendeleyev—the periodic table guy—was so taken with their work that he traveled from Russia to consult as a chemist.

Not only had I succumbed to oil myths, but I was no match for Ambassador Khazar Ibrahim. I said I’d wait until he was done with his visit.

I’ve always been suspicious of using industry as a way to frame heritage (like Pennsylvania does) because it can reduce the lives of people—and the landscapes they inhabit—to little more than appendages in the larger body of production. The result is often glorification. But at the museum I tried to keep an open mind. I told one volunteer I was exploring oil heritage in the face of new environmental knowledge and he said excitedly that he wasn’t sold on climate science, citing the fact that Greenland was once actually green. He followed with his thoughts on the sorry state of journalism post Walter Cronkite. It hit me then—duh—that people who like oil history probably like oil too. Soon I was rescued by museum educator Sarah Goodman, who offered to give me a tour.

Museums require order and organization, which is hard to map over the turbulence and mess of early extraction. Drake Well’s approach is a loose chronology of oil, starting with contextual exhibitions of early whaling, followed by some tactile stuff, like turning a lever to watch foam zooplankton compress under the weight of fake sediment. You can also smell whale oil and hold shale and study fossils. It’s quite good in that way, and in many others. Their work with archival materials, for example, helps the Pennsylvania DEP find and cap old oil and gas wells that leak methane.

Drake Well also has a huge collection of objects from the period—a nitroglycerin cart, Drake’s original top hat—but museum staging necessarily belies reality. I thought of a description of a hotel in Pithole I’d read. The proprietor wrapped the legs of his piano in newspaper each morning. Each night, the paper would be soaked with oil and mud from people brushing past it. I thought of the same thing outside as I walked through the drilling exhibits in the freshly mown grass. Can you understand early drilling without standing knee-deep in oily mud, waiting for some roughneck to flick a cigarette in the wrong direction?

Goodman told me she works hard to integrate environmental programming into school tours. They clean up a mock oil spill, for example. But the environmental impact of oil—and the long, hard ecological restoration that follows—doesn’t warrant much space on the gallery floor. I saw a few mentions of plastics pollution, and oil wars, but I was disappointed to finish the tour without seeing the words climate change or Exxon Valdez or microplastics. Goodman and Bates both said this would soon change with an exhibit dedicated to the future of energy, which will weigh the pros and cons of energy sources and emphasize individual petroleum consumption. “We want to challenge people,” Bates told me. “What can you do about plastic? The future’s up to you.”

Bates is a small, energetic woman who wore an oil derrick-themed tie and dangling pumpjack earrings. Highly knowledgeable about energy and critical of both environmental and oil propaganda, she studied the history of technology at West Virginia University and worked in public history in West Virginia and Erie before landing at Drake Well twenty-three years ago. While she “has always maintained that burning oil is a mistake,” she has little time for idealism. “Ones that come in here with an antagonistic attitude, I ask them how they got here. Acknowledge your dependence on oil, then we can talk.”

Unsure if the question was rhetorical, I told her I drove from Pittsburgh.

Brian Black had told me that “creating the public history of oil can be very frustrating because of the various competing agendas.” Bates agreed that Drake Well is behind the times on interpretation, but said the issue isn’t ideological. “It’s hard to keep up,” she explained. “And expensive.” The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission funding doesn’t cover the costs, so the museum relies on fundraising and volunteer from a partner org, Friends of Drake Well, which receives donations from individuals and businesses—including the oil and gas industry.

Friends of Drake Well has a former Pennsylvania petrochemical salesman as its board president, but Bates rejects the suggestion the industry influences museum content. “We’re not going to turn away the oil and gas companies that want to give us money,” she said. “But they can’t dictate what we say. Neither can the environmentalists who give us no money.”

Museums have a responsibility to the truth, but they also need visitors to exist. Black said as much in an earlier talk: “If you consider who is going to that museum, they’re not going to want an exhibit on climate change and how petroleum use led to these larger implications. They’re going to want to know why Drake drilled the well.” With that in mind, I stopped to chat with a couple admiring one of the replica steam engines in the park outside. They were Mike and Janet, petroleum geologists from Tulsa, Oklahoma. They were in Pennsylvania for an event at Penn State and drove three hours to see the well. I asked Mike how people should feel at the birthplace of American oil. “We should be proud,” Mike said. “I don’t see anybody riding around on horses.” He said it like I’d asked him a stupid question.

Looking down at the Pithole City Historical Site, where nearly twenty thousand people arrived in 1865 when oil was discovered along Pithole Creek. By the end of the decade, Pithole would be a ghost town. Photo by Jake Maynard.

I’d planned to tell the two of them about the most interesting oil artifact in the area, which was located a few hundred yards downstream, by the tree line, but it didn’t seem like they’d care. People walked by it along the river path unaware all the time, and if I hadn’t been told, I would have done the same. It looks a little like a collection of koi ponds—a series of oblong troughs, edged in the spring by purple phlox and reeking skunk cabbage. A couple have a sheen like a parking lot after the rain. Indigenous people dug them, and hundreds like them, all along the creek and parts of the Allegheny River. Some would be ten feet deep and originally cribbed with lumber to keep them from collapsing. The pits would slowly fill with oil and water, and the oil would be skimmed from the surface and possibly boiled to separate it.

Carbon dating puts these pits around the year 1415. There’s no consensus who dug them, but similar pits on Seneca land in New York suggest the technique was widespread. During the oil boom, the fact that Indigenous people had never fully made use of “black gold” became a point of pride in the media, another prized example of so-called Euro-American ingenuity. But now, as the check comes due for a century of burning fossil fuels, the pits offer us a lesson in restraint.

Sue Bates told me that cleaning up that area and making it more visible is another of the museum’s priorities. She’s had signage for the pits drafted since 2019, but COVID was hard on museums. “We have been too gosh darn busy,” she said. “We just don’t have the staff.” She mentioned she just started including land acknowledgments for some special events at the museum, and that there was a possibility of collaborating with the nearby Seneca Nation of Indians on interpretation of indigenous oil usage. It sounds like a good start. But for now, there’s no marker to tell passers-by what Indigenous people did—and what they did not do—with oil.

Today, much of the Oil Creek valley is a state park. Like many of the depleted landscapes in Pennsylvania, the land was acquired by the state during the 1930s for reforestation. Catastrophic flooding wrought by over-extraction had made some low-lying valleys unlivable, and the steel mills of Pittsburgh and Johnstown were often underwater. The Civilian Conservation Corps cleared the hillsides of dried brush and scrap metal and planted trees. Now, fish thrive in Oil Creek and eagles, once extirpated, are nesting. But rehabbing a landscape is a slow, expensive, and imperfect process, which is often left out of the narrative of the boom. Currently, western Pennsylvania has more than eight thousand unplugged wells—a leading cause of methane pollution—and the fossil fuel lobby is fighting legislation to help clean them up.

It’s like Black told me: “Extraction is not just removing an energy resource. The equation includes all the ancillary costs that go into it long-term. The air, the climate—all that stuff is part of the story.” The problem, though, is that we can’t always predict the ancillary costs. Many of the state’s unplugged wells, for example, were abandoned long before the state required that unused wells be plugged. It’s easy to flip through the photographs of the boom, like I’ve been doing lately, and take solace in the fact that we know so much more now. And by many measures, we do. But to be in Petrolia in, say, 1862 was also to find yourself at the edge of knowledge, wondering why it took us so long to pump the future from underground.

Pithole isn’t a part of the state park, but it is now a historical site under the administration of Drake Well. I’ve been back a few times lately, just to walk and sit, and every time I do I find myself thinking of how uncanny it is, how familiar to the story of fossil fuels. I write a lot about landscapes and impermanence, probably because I spent a lot of my childhood causing trouble in the mess left by the oil and timber industries. For me, Pithole feels almost prescient, like the slow life and death of my hometown compressed into one supersonic boom.

That’s the paradox of extractive communities: depletion is the endgame of the industry, while the goal of a town is permanence. Pithole was built so fast that new hotels were going up even as others sat empty. I read that a grocery store there was thrown together and had the shelves stocked in the same day. We don’t know if the clerks and roughnecks and chefs and sex workers thought they would be swimming in oil forever, but the editor of The Pithole Daily Record responded to the town’s decline in February of 1866 like this: “The Record is now a fixed fact: and as long as a single hole shows signs of oil, or a derrick is visible, it will continue to make its appearance…Pithole from its birth has supported a daily paper, and is likely to do so for years to come.” The newspaper moved on to the next boomtown by the end of the decade. ■

Jake Maynard’s essays appear in The New York Times, Slate, Inside Higher Ed, Chattahoochee Review, Catapult, River Teeth, Backpacker Magazine, and others.

Cover image courtesy Drake Well Museum and Park.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.