Williamson struggled with processing the emotional weight of living in what seemed like relentlessly unprecedented times. “At the time, I was thinking about them as… a place to capture competing, strong emotions.”

By Julia Shiota

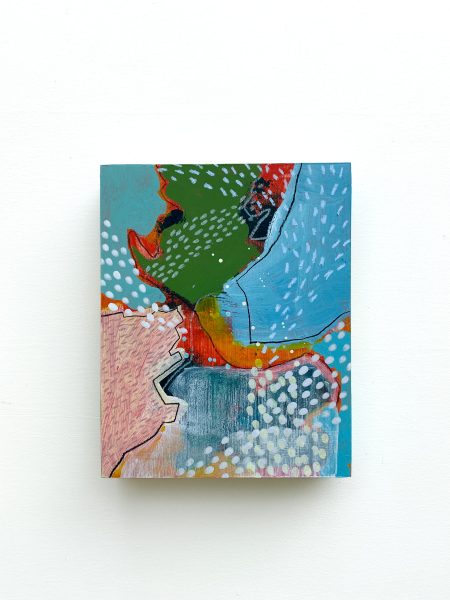

Pale pinks, milky pastel yellow, bright marigolds, sea foams, the in-between hues created where each pigment touches or overlays another. Some of these colors stand alone, solid in their vibrancy, while others are layered atop one another—gold blending into gray-slate-blue to create a sort of olive green, yellow lays in a thick film over pink. Lines of black and gold at varying thicknesses glide over this backdrop of color. Clustered in some areas of the canvas like flocks of starlings are black and white dots, their movement across the piece drawing the viewer’s eye down, up, and out beyond the confines of the 20 x 16 canvas. There is so much life here, so much movement conveyed through paint. It feels that if we were to watch the canvas long enough it would begin to move; a videoclip of life beneath a microscope or a complex ecosystem hidden within the depths of a thriving seabed.

Below the piece is the title: “there has to be some way through it”

The first time I see one of Avery Williamson’s abstract paintings, I fall in love. I came across them by algorithmic happenstance on Instagram and immediately clicked through to see more, my eyes instinctively drawn to the colors. But I found the images continued to linger with me long after I close the app itself, form and texture and color swirling in my mind’s eye. Williamson’s body of work ranges from photography, animation, collage, textile, to the dynamic abstract paintings that grace her Instagram feed and online portfolio. Each piece is a mixed-media dance of texture and color, whether existing physically or as a digital piece. Much of her inspiration comes from the materials that spark her interest in a given moment. Scattered throughout photos of her completed pieces on her feed are simple videos of her testing out a new medium, often thick single-stroke line work against a plain black or white piece of paper. Even when the tools of her creativity work against her—patchy colors, a waxy crayon that crumbles beneath her fingers—there is the enjoyment of exploration undergirding these simplest of studies.

Williamson’s affinity towards a wide swathe of materials grew out of her childhood. She describes growing up in a family where art was encouraged; her father is an artist, painter, and educator and Williamson also grew up spending a lot of time with her grandmother, a painter and sculptor. This was an environment of open material inquiry, which continues into her practice today.

As I scroll through her portfolio, the shapes and colors of her work guide my eye playfully across their textured landscapes and their seasonal shifts in color. I can’t get enough of her abstract work and the visceral response they illicit from me, even months after I first stumbled across her portfolio. I tell her this when I speak to her via Zoom, she in her home near Ann Arbor, Michigan, and I in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

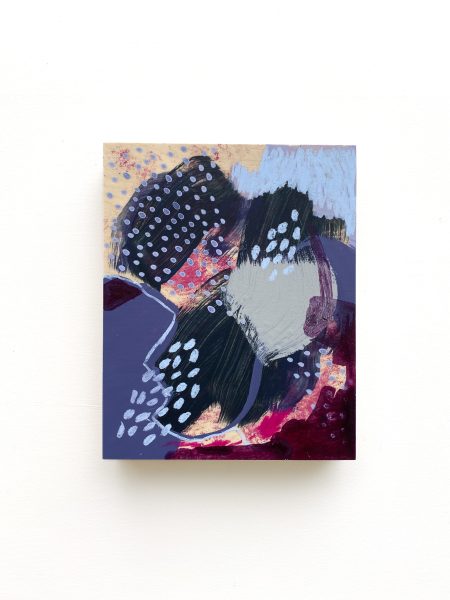

“I actually call them color bursts,” She says, “I’ve been working on this iteration of them since 2020.” Like many, Williamson struggled with processing the emotional weight of living in what seemed like relentlessly unprecedented times. “At the time, I was thinking about them as an emotional release, a place to capture competing, strong emotions that didn’t have many other places to rest or to leave my body.”

There is something meditative about the color bursts, stemming from Williamson’s artistic process. Each color burst is created over time, the color palettes inspired by what she sees around her—the changing of the seasons, what is growing in her garden, the materials that land in her hands. Each piece comes alive over time, an aggregation of colors and marks put on the canvas over the course of several months. The intention, she tells me, is to capture the range of emotions human beings feel throughout a day, week, month, or year. Because of that, the color burst are not created in one sitting. Some are created in batches, some are created on larger or smaller canvases, and some paintings are even put away completely until she feels moved to revisit them. For Williamson, the color bursts are a place to process and house the tumultuous emotions so many of us have experienced over the last three years, including the pandemic and the incessant information overload that has become part of our everyday lives.

“The color bursts have been a space to process all of that.” Williamson explains, her hands forming abstract shapes in the air as she speaks to me, “I also have a tendency to be a person who holds in their emotions, so I am working not do that. I want to find places to express emotions more regularly or to share the load of an emotion, instead of holding it all in.”

The affective complexity of her work becomes apparent in the interplay of each color burst and its title. A quick look through her portfolio reveals a flood of emotional states that all manage to resonate with me: “tender things,” “i want to be everything and nothing at all,” “Awake AF,” “pressure’s hard to take.” Williamson’s intentionality, skill, and attunement to the stories that can be told through abstraction manage to capture a range of roiling emotions that are then brought into sharper focus in the context of the titles themselves. Through abstraction there is the sense that something else exists beyond and beneath the shapes on the canvas. A sense that what Williamson brings to light can help the viewer imagine—perhaps even make—something new. Far from being restricting, the titles add another dimension to the emotional experience of viewing her work, a sort of unobtrusive guided meditation.

“The pieces are colorful and exciting and beautiful, but also they can be an expression or an aspiration towards joyfulness that isn’t always present in the making process or even in my own life.” Williamson goes on to say, “The paintings can hold all of that, they have the space to hold those emotions, which is why the titling is so important. Through the titles, I share some of what is on my mind when I made them.”

The concept of aspirational joy appears as a through line in much of her work, including her collages. Like her color bursts, Williamson’s collages rely on color and texture to tell their stories. Most often, these collages depict black-and-white pencil-drawn human figures in a brightly painted, abstracted domestic space. One collage, titled “dancing in a green room,” features three young girls against a vivid green, pink, and orange backdrop. The youthful energy and unbridled joy is tangible in the bend of their legs and the way they hold their arms out to the side for balance. All three face towards the right of the canvas and viewers are left to imagine what it is that these three girls are seeing to spark such joy.

Like the color bursts, Williamson’s collages are rooted in a deeply introspective, meditative process. It is clear that the act of making art is in itself part of how Williamson moves through the world, how she finds meaning and balance. But the pieces do more than simply act as an outlet for the creativity of a single mind, they invite viewers into a dialogue about the world they present and the emotions housed within them.

For instance, Williamson describes the collages as beginning as a way to visualize and understand her family history, “I would take my mother’s side and my father’s side and I would think of an image of a similar era—of a house, for example. From there, I would seek out images that matched up to create a fiction of them all in one moment even though they were in different places.” She explains, “The collages are lifting and transporting people into different worlds and through these pieces I try to create a moment.”

Space and region play a part in how Williamson conceptualizes the moments crafted in the collages. Like her color bursts, the color palette of the interior spaces that so lovingly house the human figures often comes from the colors she sees around her as the season change. The figures themselves are sourced from her family archives and the archives of the cities she finds herself in. In the past, she travelled around the United States and even Jamaica, collecting oral histories and combing through archives. She has since expanded to include the archives of Ann Arbor, Greater Washtenaw County, and the broader Detroit area to more deeply understand and connect with the histories of these places.

The first time I studied “dancing in a green room,” my eyes were drawn to the colors of the walls, the thick downward strokes of the window pulling my gaze down to the three girls together in the bottom third of the piece. It wasn’t until the second time I looked at the piece closely that I noticed something: the face of each figure was obscured. There are no marks of violence on their faces—no sense that there was any censorship, per se—just a gentle blurring, like a mother protectively covering the face of a child.

Williamson describes this specific stylistic element of her work as conversation around consent and as a way to think through what happens when we lift something—or someone—out of the past and place them into our modern digital context.

“I don’t like to bring people into this digital, facial recognition space,” Williamson says, shaking her head slightly for emphasis, “And because of that, I think that my line work is a way to provide privacy for these individuals while also introducing my hand into these photographs without marks of violent erasure.”

The marks we leave behind, the ritualistic feel of repeated mark making, and what the unintended consequences are of these marks permeate Williamson’s work. There is always a play on the idea of spacio-temporal collapse (a phrase Williamson attributes to fellow artist and mentor, Ricky Weaver) and what is revealed when we bring disparate times and places into contact with one another.

“When you’re looking at older documents, you are looking at the residue of technologies—of photocopies, of risograph printing, of how the hand of the clerk from whatever town is on every marriage certificate, for example.” Williamson tells me, “I am interested in the repetition of that, too, along with what it means for things degrade over time or to even eventually become the expected language of a space or ritual.”

As her work considers questions of lineage, history, and belonging, Williamson herself is situated within the long history of Black abstraction. It has taken her some time to discover this artistic lineage for herself. She describes much of her post-college education as discovering what other artists she is in conversation with, to fill in the gaps left by her formal artistic background. In particular, she tells me about Howardena Pindell, the prolific American artist and curator, who also works in abstraction and collage. In 2018, Williamson went to Pindell’s exhibition, Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. In Pindell’s work Williamson encountered color, shape, and scale in ways that she says she had never considered before. Coming into contact with the work of artists like Pindell and Alma Thomas, another influential Black artist who worked in abstraction, has changed her career trajectory, she says.

“They have given me so much more language and validation in how abstract work allows you to process, to make sense of, to assert something, to challenge the viewer and yourself in ways that are so powerful. So often words are not able to capture what is happening or how we are processing things, and I think abstraction can be really powerful in these moments.” She tells me, her passion coming through in her voice and the way her face lights up as she speaks about these women.

I still feel that ineffable surge of feeling when she shares a new piece with us, of that something that she is so good at tapping into. And I remain excited for the work that she will continue to create, the other artists she will inspire as one thread within the lineage of Black American artists, following in the footsteps of the artists she so admires. For all her accomplishments thus far and the sheer scope of her talent, Williamson is still in the early stages of her career. There are still so many more pieces, projects, and exhibitions for her to create, and more stories for her to tell. She has created space and possibility, not only for herself, but for those who came before her and those who will come after,

“I always think about giving space in the work to the complexity of all my ancestors.” She says as we wrap up our discussion, “I can’t put words in the mouth of people who are not alive or who are not opting to be in this space, but I want to create work that allows viewers to ask questions and to challenge viewers as a way to honor and to continue to make space for the past.”

Julia Shiota is a writer and editor from Minnesota. Her fiction and nonfiction work have appeared in Catapult, the Asian American Writers Workshop, Poets & Writers and elsewhere. When she isn’t writing or reading, she’s most often knitting or listening to Prince.