Alison Vilag pays attention for a living. She counts migrating ducks at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory, near Paradise, Michigan. It’s key to getting a pulse on different bird populations. But for Alison, counting ducks is more than just science – it’s an escape from the expectations of others.

By Dan Wanschura

The following transcript is from an episode of Points North, a narrative podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

DAN WANSCHURA, BYLINE: Alison Vilag is on her morning walk in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. It’s just before sunrise in the middle of May. She’s making her way through a stand of jack pines toward Lake Superior.

ALISON VILAG: I’m hearing a flock of black-capped chickadees right now. Good morning chickadees.

Good morning, peeper. Time for you to go to bed.

I always try to just center myself when I’m walking out to put myself in like that space of observation by paying attention to what sounds are on the boardwalk, where it sounds like the wind is coming from.

WANSCHURA: Alison is 30 years old, but she still has a childlike sense of awe and wonder at the things around her.

Things you and I might never take the time to notice

– she does.

(Nashville warbler singing)

VILAG: Good morning, Nashville warbler.

WANSCHURA: You could say, Alison Vilag pays attention for a living. During the spring months, she’s a waterbird migration counter at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory near Paradise, Michigan. It’s her job to count the different types of ducks heading north to their summer homes. On a good day, thousands of birds will cross Lake Superior here. But for Alison, counting birds is not just about numbers and science. It’s an escape.

VILAG: A lot of my Saturday mornings were not spent in church, but out looking for birds in wonderful natural places. And I think that was the point when I started connecting birds with escape. And that theme has totally continued for a while and – for a while – who am I kidding? Until now and who knows about the future?

WANSCHURA: This is Points North. A podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura. Today on the show, how birds helped Alison break free from other people’s expectations.

Caption: Alison Vilag looks through her spotting scope at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory on May 18, 2023. (credit: Dan Wanschura / Points North)

WANSCHURA: One day, when Alison Vilag was six years old, her dad asked if she wanted to look for ducks instead of taking a nap. And when you’re six, anything is better than a nap.

VILAG: So yes, I wanted to go look for ducks. And we went out and we looked for ducks, and we saw a northern shoveler, which I thought was a mallard. I didn’t really believe my dad cause they both have green heads.

WANSCHURA: Alison’s fascination with birds took off from there. Her parent’s had a field guide book about birds – she used it to learn everything she could about different species.

VILAG: I don’t think anybody involved in that first birding outing imagined how much of my life I was going to spend looking for ducks.

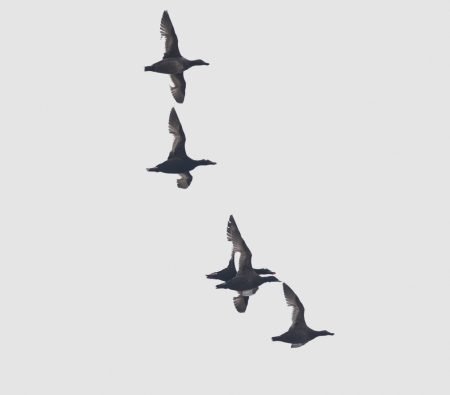

A flock of long-tailed ducks cross Lake Superior during a migration flight. (credit: Alison Vilag)

WANSCHURA: As she got older, birds became even more of an escape. Alison was raised in a Seventh Day Adventist Church in southwest Michigan. It’s a church that has close to 22-million members worldwide, according to the most recent data. Alison says her family’s congregation was pretty restrictive. You couldn’t do things like drink coffee, listen to syncopated music, or play cards. Sabbath, which is Saturday for Seventh Day Adventists, is an intentional day of rest. Alison says there were even more rules to follow that day.

VILAG: You couldn’t go swimming, you couldn’t play board games. I remember that we had the church bulletin, and it would say what time sunset was on Saturday night. And my friends and I would all set our alarms for that time because cool, we could do fun things again as soon as that was over.

WANSCHURA: When she was in middle school, Alison remembers studying a curriculum through her church. It was meant to prepare and inspire her for womanhood. But instead, it was one of the darkest times of her life.

VILAG: Because it seemed like my only purpose in life as a young woman was to prepare myself to become a pure and godly wife.

WANSCHURA: Being a Godly wife largely meant getting married, staying home and raising kids.

VILAG: I was more interested in doing other things. I wanted to be, I think at that time, a field biologist and study birds. Despite all the rules, Alison says Adventists were allowed to go outside and bask in God’s creation on the Sabbath instead of going to church. It wasn’t okay, for example, to go out and look for birds competitively. If you were trying to see as many birds in a day as you could, for example, that was not okay, but just going out and looking for birds and enjoying being outside … what better way to learn about creation and to observe creation than to be out in it. Sometimes her mom or dad would join. But most of the time it was just her – alone in the woods. I just remember walking around and being in like a beautiful old growth forest and thinking that, okay, I’m not sure exactly what I think God is, but I know, whatever that concept is, I feel much closer to it out here in the things that, according to the Bible, God has created instead of in buildings that were made – they don’t have that direct conduit. And so being out in nature was a much more sacred place.

Points North executive producer Dan Wanschura and Alison Vilag look for migrating birds at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory on May 18, 2023. (credit: Nick Loud / The Boardman Review)

(sounds from Whitefish Point)

WANSCHURA: Whitefish Point has been that direct conduit for Alison Vilag. It’s a wild, rugged place in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The point itself is surrounded on three sides by Lake Superior and is a natural corridor for migrating birds.

VILAG: Oh, there’s a line of ducks out there. That’s pretty cool. What are you guys going to be? Scoters! And some scaup mixed in. I like scoters a lot.

WANSCHURA: Scoters and scaup are ducks. These birds are headed to far northern Canada. Out near the tip of Whitefish Point, there’s a small covered shack about the size of a telephone booth. When the weather is really bad, Alison counts ducks from inside that shack. She says Whitefish Point has a reputation of being a bird observatory with one of the worst field conditions in North America. But still, she loves it here.

VILAG: It just seems more gratifying when you’re out here. You can barely use your scope cause the wind’s shaking your tripod so bad. And ducks are still flying and that sort of weather. It just – it blows my mind sometimes…Waterbirds, man – they’re pretty tough.

A flock of white-winged scoters, migrating near Whitefish Point Bird Observatory. (credit: Alison Vilag)

WANSCHURA: In 2001, Alison’s parents brought her to Whitefish Point for the first time. She was nine, and it was during the spring migration. She remembers visiting the waterbird shack and meeting the duck counter that year. Alison was learning some birding lingo too and was eager to show it off.

VILAG: There was a big common loon day, and they were flying over the shack. And I just looked up, and I’m like, “Oh yeah, another, another loon – a trash bird.”

WANSCHURA: In the birding world, a trash bird refers to a bird so common it’s considered less desirable than another, more rare bird.

VILAG: I can only imagine what that counter that year must have felt to have this little smart ass kid that was just like, “Yeah, trash bird.”

WANSCHURA: She didn’t know it at the time, but that would become a defining memory for her. Today, Alison uses a pair of binoculars and a spotting scope to help identify and count the ducks as they fly by. She uses hand clickers to count – different ones for each kind of bird.

(sound of the hand counter clicker)

VILAG: Those two really high ones are red-throated loons. There’s a common loon out front. And then looks like mergansers. Fourteen.

A common loon during its migration flight. (credit: Alison Vilag)

WANSCHURA: Whitefish Point Bird Observatory was created in 1979. Alison started counting here in 2019. Workers count migrating ducks year after year to get a better idea of populations and other changing trends.

VILAG: Five-hundred forty long-tailed ducks in the first hour. That’s pretty incredible.

WANSCHURA: When Alison was in her early twenties, her mom developed cancer. As it quickly spread throughout her body, Alison says her mom’s personality changed dramatically.

VILAG: My mom went from being this wallflower into like the most exuberant, outgoing person that any of us had ever seen. Nobody could believe it.

WANSCHURA: Looking back, Alison says as a first generation Seventh Day Adventist, her mom had a hard time making friends in their church.

VILAG: She definitely believed in a lot of the things that makes that church what it is, but I think that she was just different enough from the people that had been in it their whole lives that she didn’t feel like she belonged.

WANSCHURA: When her mom passed away, Alison was living in Chicago. But she needed a change. The first place she went: the Upper Peninsula. That’s when she found herself back here at Whitefish Point for the first time as an adult. Another escape.

(sound of clicker counting)

VILAG: I just picked up on a flock of distant– I believe that they’re red throated loons. They’re probably six or eight miles out.

WANSCHURA: Alison says loon flocks fly loosely – almost like constellations moving through the sky. Now, common loons are some of her favorite birds to observe.

A migrating common loon in flight. (credit: Alison Vilag)

VILAG: I guess my loving loon flight as much as I do now has been an atonement … for me saying that it was a trash bird when I was a smart little kid.

WANSCHURA: Alison says sometimes birding can instill a mindset of just checking birds off a list. To focus on the status of a bird, instead of what she calls the essence of a bird.

VILAG: It’s more about conquest and I’m more about connection.

WANSCHURA: Today, Alison Vilag orients her entire life around migration. In the spring and fall, she’s counting birds. In the summer, she bartends to make money. And in the winter, she writes. She also left the Seventh Day Adventist church in her early twenties.

VILAG: When I’m immersed in a season of migration, counting is definitely the closest thing to, you know, a Biblical example of a good person – just to use that as a marker. I’m living from a space of love and care and consideration.

(sound of Lake Superior waves)

Canada geese fly across Lake Superior with a huge freighter in the background. (credit: Alison Vilag)

At the end of every migration season, Alison is sad to leave this place. She says Whitefish Point is a place where she never feels stagnant. It’s her paradise.

VILAG: Long hours of quiet and figuring out who you are and who you want to be. It’s a good place to do that. Oh boy, there’s a distant long-tailed flock. That’s pretty big. With a scoter flying with them.

For more stories from around the Great Lakes, listen and subscribe to Points North wherever you find podcasts. Apple | Spotify

Dan Wanschura is an award-winning reporter and storyteller based in northern Michigan. He is the host and executive director of Points North, a podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. Some of his favorite stories include meeting a world-class pipe-maker living in the Upper Peninsula, learning the meaning behind the phrase, ‘Thin As A Rail,’ and recounting a harrowing ice fishing trip that nearly turned deadly. Dan lives near the shores of Lake Michigan with his wife and son.