A Pennsylvania bill that would limit fracking near homes and schools was shelved this summer right before a scheduled committee vote. In a small town in shale country, accounts of misery and discord show the stakes.

By Quinn Glabicki

This story was originally published by PublicSource, a news partner of Belt Magazine.

In Marianna, the headaches began just as soon as the drilling did.

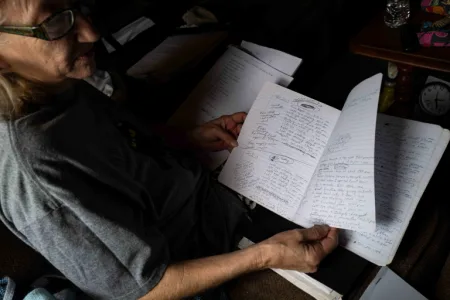

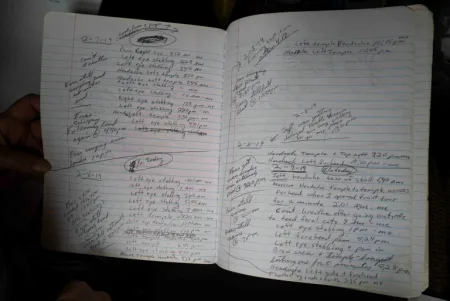

Seated in her living room in the Washington County borough of around 500 on an afternoon in August, Kimberly Laskowsky flipped through pages of notes she’s kept through years of deteriorating health. She started chronicling after EQT’s Gahagan well pad was built 850 feet away in West Bethlehem Township.

Laskowsky recorded 374 migraines in one month after the drilling began in 2019. “Like someone stabbing my head with a knife,” she wrote.

She had always had low blood pressure, but since the frack it’s been chronically high, “up near 200,” she said. In August 2021, Laskowsky collapsed on her bathroom floor.

That year, the trees across the street lost their leaves in August, Laskowsky remembered.

Kimberly Laskowsky sits in her living room in Marianna, Washington County, approximately 850 feet from EQT’s Gahagan well pad.

In Pennsylvania, state law allows drilling up to 500 feet from a home. Across the commonwealth, nearly 1.5 million people live within a half mile of active oil and gas wells, compressors or processing stations. In Washington County, the most heavily fracked in the state, more than half of residents live within that radius.

Drilling near homes occurs against the backdrop of mounting scientific evidence which correlates fracking and health problems. Last month, joint studies by the Pennsylvania Department of Health and the University of Pittsburgh found a 5-to-7-fold greater risk of developing lymphoma among children within one mile of a well. A separate study found that people with asthma are four to five times more likely to have an asthma attack if they live near wells even after fracking is complete, during production. Toxic hydrocarbons commonly linked to fracking like benzene are listed by the Environmental Protection Agency to cause dizziness, headaches, anemia and neurological disorders.

Last year, researchers from Yale School of Public Health found that children within 2 kilometers of at least one fracking well were two to three times more likely to develop leukemia and suggested that existing setback distances “are insufficiently protective of children’s health.”

In 2020, the 43rd Statewide Grand Jury found that the current state setback rule barring drilling within 500 feet of homes is “dangerously close” and inadequate for the protection of public health, recommending a 2,500 foot buffer. “An increase in the setback, to 2,500 feet, is far from extreme, but would do a lot to protect residents from risk.”

The report concluded: “The closer you live to a gas well, compressor station or pipeline the more likely you are to suffer ill effects.” Josh Shapiro, then the attorney general, pledged to implement the report’s recommendations during his successful campaign for governor last year.

Despite this, legislative efforts to keep drilling at bay have stalled in Harrisburg. And in the absence of a more restrictive state setback law, small municipalities like Marianna and their residents have been left to fend for themselves.

No reforms from Harrisburg

In February, shortly after Shapiro was inaugurated, the state Department of Environmental Protection [DEP] formed a working group to review the findings of the 2020 grand jury report and determine what, if anything, the state should do.

According to DEP Press Secretary Josslyn Howard, the group is composed of agency legal experts, program deputies and executive staff, and is led by DEP’s chief counsel, Carolina DiGiorgio.

On June 26, Richard Negrin, then-acting DEP secretary, told a Senate committee that he expected the group’s findings by the end of the summer.

State Sen. Gene Yaw, R-Williamsport, raised what he called a “serious concern” with legislation that was scheduled for a vote the following day. House Bill 170, if passed, would follow the recommendations of the 43rd Grand Jury and expand Pennsylvania’s no-drill zones to restrict fracking within 2,500 feet of homes and 5,000 feet of schools or hospitals. Yaw said he had received a memo from the DEP’s legislative affairs director indicating the administration’s support for the bill.

“For all practical purposes, that would shut down about 99% of the drilling in the most productive areas in Pennsylvania,” Yaw said. “If it’s your intent to ban drilling, then let’s say, ‘We’re going to ban drilling.’”

In a statement this month to PublicSource, Marcellus Shale Coalition President David Callahan called HB 170 and similar setback proposals a “backdoor ban” on natural gas development, adding: “These proposals are not grounded in fact or science and ignore Pennsylvania’s strong regulatory framework, the continued technological advancements that allow us to continue to produce natural gas safely and responsibly, and the economic and environmental benefits shared by all Pennsylvanians.”

Kimberly Laskowsky flips through pages of notes chronicling her deteriorating health since EQT’s Gahagan well pad was built 850 feet from her home in Marianna.

The day after Negrin’s committee appearance, state Rep. Greg Vitali, D-Delaware County, received an unexpected phone call. Vitali, the majority chair of the state’s House Environmental Resources and Energy Committee was set to preside over a vote on HB 170. Three years after the grand jury report, Vitali was confident the legislation would pass committee; he had secured enough votes to send the bill to the House floor. And with his party now holding a slim majority, it stood a chance.

But at the eleventh hour, Vitali reversed course. “Here’s the situation,” he told the committee. “Five minutes ago I was called by [House Democratic] leadership and asked not to run these bills,” including the setback proposal and an unrelated moratorium on new air quality permits for cryptocurrency data mining facilities.

“I am deeply disappointed by this decision but I am going to comply with the wishes of my leadership,” he continued, before abruptly adjourning the meeting.

For Vitali, the bill had been an opportunity to make a statement that the health of citizens is more important than the oil and gas industry. “Regrettably, we failed,” he later lamented. “We made just the opposite statement. Special interests prevailed yet again in this building.” By killing the legislation in committee, Vitali suggested that the Democratic leadership was protecting its caucus from a potentially uncomfortable public vote, and signaling that the priority is maintaining broad electoral support. Had he held the vote anyway, Vitali said he was told he could face “consequences”.

Neither House Speaker Joanna McClinton nor Majority Leader Matt Bradford responded to PublicSource’s requests for comment.

“Our caucus has failed to prioritize environmental policy,” Vitali said.

DEP spokesperson Howard said the agency will collaborate with the Department of Health and the Office of the Attorney General and will move to conduct “independent scientific research and analysis.”

Howard said the agency will have more information on its deliberations on setback legislation and other reforms in the coming weeks.

Ten Mile Creek separates Marianna Borough and West Bethlehem Township.

‘No opportunity to say no’ in Marianna

Marianna, the former coal mining community in southern Washington County, once attempted to prevent industry from encroaching on its doorstep. Several years ago, Marianna and the much larger West Bethlehem Township began to work on a “joint venture” that would limit how close drilling could come to local homes, according to Thomas Donahoo, a supervisor in West Bethlehem.

Silva, then-council president in Marianna, said he had traveled to other small towns to see the industry’s impact. “It was appalling. For smaller communities, they really had no regard for anything.”

Jeremy Berardinelli, Marianna’s council president, attends to paperwork in the borough’s municipal building.

As the neighboring municipalities considered new zoning that could restrict drilling, officials said, EQT donated money to local causes, including to the local library, a local Christmas parade and $1,000 for a baseball field backstop.

“If we reached out and asked for help, they helped us,” said Jeremy Berardinelli, Marianna’s current council president.

By Silva’s account, the company presented to the borough and the township and promised jobs, asking locals: “‘How would you feel if we could bring this town back to life?’ It painted a picture as though big things were going to happen.”

EQT did not respond to questions from PublicSource.

Both municipalities drafted zoning ordinances and discussed a 1,000 foot local setback, according to Silva and Donahoo.

When Marianna’s council held a meeting including a vote on the zoning proposal, it drew several EQT representatives. Meeting minutes from that day show that state Sen. Camera Bartolotta, R-Washington, was also there in the cramped cinder block building. In a 3-2 vote, Marianna’s council passed a zoning code, but it defers to the state’s 500-foot setback minimum.

West Bethlehem’s supervisors, after drafting a zoning regulation, never voted on it, according to Donahoo, and the township has no regulations to limit drilling near homes.

Wesley Silva, the former council president in Marianna, stands outside his home in the borough. “Had the regulations been in place, this wouldn’t have happened to small communities like Marianna,” he said.

EQT developed the Gahagan Pad in West Bethlehem Township, just beyond 800 feet from where Laskowsky and Boardley live in Marianna.

“There was nothing we could do on the borough side to stop it,” said Berardinelli. He opposed the Marianna ordinance in 2017, but has concerns with well pad proximity to homes. “Public safety is paramount,” he said. “It just shouldn’t be that close to a residential area.”

As Silva sees it, a more restrictive statewide setback law would give smaller communities legal recourse to keep industry at bay. “It would level the playing field for a lot of communities,” he said. “Had the regulations been in place, this wouldn’t have happened to small communities like Marianna.”

Laskowsky recalled an interminable tapping and a high-pitched whine as EQT drilled. On several nights she resolved to leave, sleeping in her minivan down the street to escape the noise and the lights and the fumes.

Boardley, who also endured migraines, recalled vibrations that shook her home with such vigor that ornaments fell from the shelves.

“I have enough chemicals in me to be living right down on that pad,” said Laskowsky.

Urine samples collected in August 2019 showed Laskowsky and her granddaughter both had elevated levels of metabolites of the volatile organic compounds toluene, ethylbenzene and benzene, a potent carcinogen.

Tammy Boardley looks out her bedroom window towards EQT’s Gahagan well pad. “It sucks to be us sitting here,” she said.

Now that efforts at both the state and local level have failed to rein in fracking, Marianna residents fear things are only poised to worsen.

There’s a new well pad under construction along the borough’s border, and another up the road.

“You get cancer from this stuff. That’s what I hear,” said Boardley.

“It sucks to be us sitting here.”

Photographs by Quinn Glabicki.

Quinn Glabicki is the environment and climate reporter at PublicSource and a Report for America corps member. He can be reached at [email protected] and on Instagram and X @quinnglabicki.

This story was fact-checked by Punya Bhasin.

PublicSource is a nonprofit media organization delivering local journalism in the Pittsburgh

region at publicsource.org. You can sign up for their newsletters at publicsource.org/newsletters.