Fire!: An American Burning is a five-episode podcast series that delves into the stories of twentieth and twenty-first century industrial fires in American cities and their profound connection to contemporary climate crisis, produced by Belt Magazine and hosted by Ryan Schnurr. Episode One is “Fire on the Cuyahoga (Cleveland, OH),” on the Cuyahoga River fire, Carl Stokes, and the interrelated struggles of a mid-century industrial city.

TRANSCRIPT

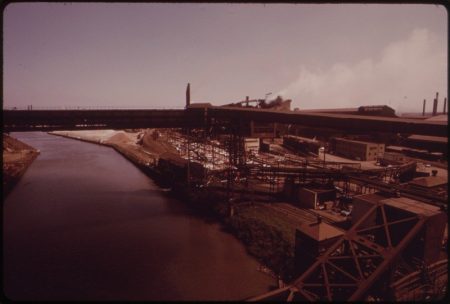

HOST: Okay, so, picture this: You’re in Cleveland, 1969, in an area called The Flats, near the banks of the Cuyahoga River. It’s a pretty heavily industrial area—across the way is the Republic Steel Mill. The river is thick with sludge, and a skin of oil is slicked across the top. A train grumbles over a wooden bridge.

It’s a Sunday morning, late. A spark leaps from the train and burns through the air. Or maybe somebody tosses a cigarette or sets off a flare. That’s not totally clear. Anyway, the spark lands on the Cuyahoga oil slick, which ignites. The river is ablaze.

Joe Mosbrook: “That fire seems to get bigger every year in passing.”

Source: Environmental Protection Agency/Frank J. Aleksandrowicz (public domain)

HOST: That’s Joe Mosbrook. He spent thirty-five years as a reporter in Cleveland, mostly for NBC radio.

JM: “The day it happened, I was working at the station as a radio newscaster, and we covered it as a minor fire along the river. It happened any number of times in the past.”

HOST: Somebody calls it in. The fire department comes out and sprays things down. It’s out pretty quickly. There’s some slight damage on the bridge, and the next day there’s a story in the newspaper, buried in section C, next to an ad for shampoo: “Oil Slick Fire Damages 2 River Spans.” And, originally, people thought that would be it.

JM: “But all these timing pieces came together somehow, I think, and this 1969 fire sort of became—for Cleveland, anyway—a symbol of that awakening towards environmental problems.”

# MUSIC: THEME

HOST: From Belt Magazine, this is Fire—a podcast about industrial fires in American life. I’m Ryan Schnurr. Each episode in the series tells the story of a different fire—a river in Cleveland, a factory in New York, an oil refinery in Indiana, a coal mine in Pennsylvania, a wildfire in California, and what they reveal about the complexities of life in the industrial United States

This episode, episode one, is about the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969. And, actually, this is the one that got me thinking about industrial fires in the first place. Because there’s this whole mythology that’s welled up around it—about Cleveland and the environmental movement and the EPA.

These days, the Cuyahoga is much cleaner. Fish and other aquatic animals are back. People boat on it. I didn’t see a single oil slick. But the Cuyahoga River fire has become shorthand for a particular, derogatory image of Cleveland, a low point in the history of regional industry.

It’s pretty amazing, when you think about it, that we’re still talking about the river fire all these years later. Because this wasn’t the only fire the river had ever experienced, or even the largest. On the grand scale of American disasters, it barely registers as a blip. But for some reason, this is the one that occupies a looming place in the U.S. cultural imagination, as a symbol of our triumph over industrial pollution.

But, it turns out, the story is much more complicated than that.

# MUSIC

HOST: In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Cleveland was a fairly typical Rust Belt town. It had been at the center of John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil empire and grew into a major hub for the steel and oil industries. But the late ‘60s were really a moment when a lot of key twentieth-century transformations were coming to a head in Cleveland and in the United States more generally.

David Stradling: “To my mind, there, there are two really important trends to keep track of.”

HOST: This is David Stradling, a historian at the University of Cincinnati. He co-wrote a book called Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland.

DS: “And one is the developing urban crisis in the United States, which is hitting Cleveland particularly hard and early. …The other part of it is a recognition of the environmental crisis that has been developing, sometimes for similar reasons. But sometimes for very different reasons, at exactly the same time.”

HOST: First, the urban crisis, which is basically caused by declining industrial activity and loss of jobs in cities, plus white flight.

DS: “The city of Cleveland is having budgetary issues, in part driven by deindustrialization, in part driven by the fact that lots of people are leaving the city for the suburbs, particularly whites who are able to move into suburbs.”

HOST: As the jobs and white people fled the city, a lot of wealth went with them, leaving an urban core that was disproportionately Black and immigrant, disproportionately poor, and that was beginning to deal with the legacies of industrial production.

Yanick Rice Lamb: “Then you have—the people who are left behind are people from, you know, different racial or ethnic groups that are living closer to the plants, or they’re being built there, where they’re located.”

HOST: Yanick Rice Lamb is a journalist, medical sociologist, and professor at Howard University who studies the legacies of industrialization in Ohio.

YRL: “A lot of the urban areas in Ohio have high concentrations of industry, or they had it or they still do. So you’re talking about Cleveland, Toledo, Dayton, Columbus, Cincinnati, but as well as Steubenville and Youngstown and some other places.”

HOST: The byproducts of oil and steel production clogged the air and spilled over into the waterways like the Cuyahoga River. Plus, civic infrastructure was failing—namely, sewage and wastewater overflow systems.

YRL: “… Studies show that some of the contaminants, they kind of go for a widespread area, but of course, it’s more concentrated the closer you are to the plant….”

HOST: People of color, particularly Black people, are more likely to experience the harmful effects of industrialization, like health issues and disinvestment.

YSL: “But also, in some cases, people ended up in the neighborhoods, even after the, you know, factories or landfills were already there. Because that’s where a lot of communities of color—a lot of people were pushed there. So that’s the only place they could live.”

HOST: And this was all because of decisions that were made by governments and corporations. Redlining, racist zoning policy, waste dumping, stuff like that.

YRL: “So those neighborhoods were also more vulnerable to any kind of…urban renewal. So that also impacted generational wealth in terms of the ability to take better care of yourself and have better access to health care, and all of that, because some people got displaced…Or it didn’t quite hit their house, but it hit their neighborhoods or it created a dead end street…. and it lowered their property value, so they couldn’t sell….and then if they lost a job because of deindustrialization, it was kind of another catch-22 which was part of that…And so it was like a domino effect.”

DS: “The need for infrastructural investments in the late 1960s was really intense, particularly building new sewage, developing better sewage systems…. all of this stuff requires an awful lot of, of cash layout that, that cities like Cleveland are increasingly having difficulty keeping track of.”

# MUSIC:

HOST: Then, in 1967, amid the interlocking crises of cities and environment, Cleveland elected Carl Stokes, one of the first Black men to be elected mayor of a major American city—and the first to be elected mayor of a majority white city.

DS: “He does not win the majority of white votes, but he wins enough white votes to become mayor. And, once there, he has remarkable command of all of these various problems that are running through Cleveland. He understands how terribly polluted Cleveland is, he understands the housing issue firsthand—he grew up in public housing.”

HOST: Here’s Stokes, speaking at UCLA in November of 1968—about a year after the election, and less than a year before the fire:

[TAPE] Carl Stokes: “We in uh—in Ohio, once again we hold a certain kind of distinction—at water pollution conferences around this country, they refer to the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland and Lake Erie, upon which we border, as the only two bodies of water that they know of that constitute fire hazards… [laughter] …well…”

HOST: But the speech is about more than the river—it’s about why the river, and Cleveland more broadly, are in the state that they’re in.

[TAPE] Carl Stokes: “And so as one of the beleaguered mayors of the one of the big cities of this country, I just thought I’d talk with you today about how bad our cities are which is a common kind of topic, but moreover to try to explain how they became bad…”

HOST: He outlines a variety of issues, like population shifts, urban renewal, and underinvestment in critical infrastructure like housing and transportation. Plus, a lot of the pollution in the Cuyahoga came from suburbs and suburban factories, which would dump in the river upstream, and then that sewage or wastewater would flow into the city. So all of this is contributing to the problem of urban pollution—but, because these communities were outside of their jurisdiction, or had permits from the state of Ohio, Stokes and the city of Cleveland couldn’t do anything about it.

Anyway, the point is that at the end of the 60s, the city’s infrastructure is in pretty bad shape, its budget is tight, and it’s on the receiving end of a lot of industrial runoff and other byproducts that are causing problems for the community.

And then the Cuyahoga River catches on fire.

# MUSIC

JM: “I’ve forgotten how we got there that day. But it was right on the river, obviously—there was a railroad trestle across the river, down the hill from where we are now.”

HOST: Joe Mosbrook was covering city hall and the mayor. And, on the day of the fire, he was called out to a news conference. Recently, we met up and went down by the river where the fire happened—or as close as you can these days without trespassing. To get there, you drive through a tangle of industry—pipes, railroad tracks—and down a long public road that dead-ends into an industrial facility.

JM: “And the bridges were still there. The trestles were still there. They were charred. There was—you could see there’d been a fire. But we were standing up there on top of the trestle holding the news conference.”

HOST: Stokes had brought everybody out to take a look at the river.

JM: “He liked to dramatize his press conferences, so he would take them on the road to get some visuals—he was aware of television, things like that. And he had us come down, and we were standing on the charred trestle, and he said: ‘We have to do something about this, I’m going to talk to the state it’s their responsibility. They ought to do something about all this pollution in the river.’”

HOST: He had decided to make an example of the fire, to try to get some things addressed. He took the press corps on a tour of four sites, including the trestle, the old Hershaw Chemical Company upstream of the fire, an elevated sewer called the Big Creek Interceptor, and a sewer in the Village of Cuyahoga Heights.

DS: “Part of Stokes’s genius, I think, is his ability to make connections. And to make those connections apparent to other people.”

HOST: David Stradling again.

DS: “…I think the number one goal that he’s trying to achieve is to make connections between not just the burning Cuyahoga—this is not just a problem of the Cuyahoga, it’s a problem of the urban environment more generally. And even more important than that, it’s a problem of the relative powerlessness of the city of Cleveland.”

HOST: So after his press conference, Stokes goes on the road, and he says, this is the moment to really push for substantial change in Cleveland and in urban American more broadly. And he’s joined in this effort by his brother, Louis Stokes, who was the house representative for Cleveland’s east side.

DS: “They gain the ear of Washington, I would say. Stokes comes to testify before Congress a number of different times on a variety of different issues, environmental and housing.”

“…I think he’s pretty good about making the country recognize that Cleveland is in crisis and needs help…He is describing to the press an understanding of the urban and environmental crisis that reflects back on power relations inside of the United States.”

#MUSIC

HOST: Six weeks later, in August, Time magazine published a splashy magazine story with an image of the river on fire—a wall of black smoke rising out of a row of flames. There are firefighters on the bridge spraying water. It’s a pretty dramatic image. And it took people like Joe Mosbrook by surprise.

JM: “Well, the first thing was, where the heck did they get that photograph? I mean we were––I have not seen a picture of the ‘69 fire actually burning. There were a couple of pictures where the fire boat is over there later spraying down the charred trestle. But I can’t remember ever seeing flames in any picture.”

HOST: That’s because no such picture exists. The fire itself had been put out so quickly that the only photos were the ones Mosbrook has seen, with the fireboat. It turns out the Time photo was from a 1952 fire, the last one prior to ’69.

JM: “But the reaction was, here’s Time using an almost twenty-year-old picture to depict something that happened a month ago.”

HOST: The photo, like the Time story, painted the picture of this massive, sensational event. It was the kind of thing that would make you pick up a paper—unlike the ’69 photos. And it did.

Usually, this next part of this story is about how the fire captured the national imagination and led to the formation of the EPA and the Clean Water Act in 1972.

DS: “And that’s because it makes for a tidier story, right? …Which is the narrative that the Time magazine article helps cement in people’s minds… urban America is getting more and more polluted to the point where we have these ecological catastrophes like a river catching fire.”

HOST: But it’s actually more complicated than that. For one thing, there was already a lot of energy around environmental protection at the federal level. Here’s Richard Nixon, in his first inaugural address, January 1969:

[TAPE] Richard Nixon: “In pursuing our goals of full employment, better housing, excellence in education; in rebuilding our cities and improving our rural areas; in protecting our environment and enhancing the quality of life—in all these and more, we will and must press urgently forward.”

HOST: In 1962, Rachel Carson published a book, Silent Spring, which was about pesticides and contamination. Silent Spring was serialized in the New Yorker, and became a massive hit. It’s widely credited with spawning the modern environmental movement

Another contributing factor was a 1965 report on pollution in the Ohio River, known as “Troubled Waters.”

[TAPE] “Troubled Waters”: “The special subcommittee on water pollution will be in order. In the course of these hearings, the subcommittee will objectively examine and inquire into the whole breadth and scope of the water pollution problem facing the nation.”

HOST: The report was turned into a half-hour documentary film, narrated by the actor Henry Fonda.

[TAPE] TW: “Man uses the waters of the earth to quench his thirst, to grow his food and prepare it. …To make all the goods he uses every day—steel, oil, coal, cotton, wool, plastics, leather, glass, chemicals. And all of these activities change the water, alter it, remove some of its natural purity, add undesirable substances.”

HOST: And then, in January, 1969, roughly six months before the Cuyahoga River fire, an oil well exploded near Santa Barbara, California, spilling three million gallons of oil into the water and creating a thirty-five-mile oil slick up the coast. The Santa Barbara spill was sensational—it hogged the headlines and TV screens and tuned the public’s antennae toward environmental disasters.

DS: “I don’t think you can give too much credit to the Cuyahoga fire for the Clean Water Act. It was mentioned during congressional debates…but the suggesting that that fire had to happen to create Clean Water Act, I think is not true.”

HOST: But the Cuyahoga River fire also wasn’t nothing. I mean, people did pay attention, including people with a lot of power. And the event really became symbolic of this larger environmental movement that was happening.

Randy Newman even wrote a song about it, called “Burn On.” I really wanted to play the song here, but I couldn’t get the rights, so you’ll have to find it yourself online. It’s Randy Newman, so it’s a kind of parody, sending up the whole idea of a romanticized city songs, as well as Cleveland itself, by memorializing this industrial image of a burning river.

# MUSIC

HOST: But this story obscures a lot of what was happening behind the scenes as communities organized for change. This was an era when movements were coalescing—the environmental movement, the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and the movement for environmental justice.

YRL: “So at some point, lots people are getting sick and dying” …Or their skin was being irritated. And that kind of thing— or they’re coughing and so they’re like, what’s going on here? They, they started realizing that some of the things they’re dealing with aren’t healthy.”

HOST: Environmental justice really picked up steam in the 1970s. Rice Lamb says its central idea was similar to what Stokes encountered in Cleveland—that marginalized people (namely poor people and people of color) were disproportionately feeling the effects of these interlocking crises.

YRL: “Robert Bullard, who runs the Center for Environmental Justice at Texas Southern…He’s done a lot of research. He’s considered the father of environmental justice. And then Ben Chavis, who had been with NAACP later afterwards, but he was involved in some protests in North Carolina and kind of coined the term environmental racism.”

HOST: So environmental justice said, we ought to organize, and we ought to leverage our power to fix these disparities—which, by the way, are all interconnected.

YRL: “Everything’s, you know, the economic, educational, housing, medical, all these different labor issues. They’re all connected and, and they’re all considered social determinants of health.”

HOST: If any of this sounds familiar, it’s because environmental justice continues to be important today. Youth organizers now talk about “environmental liberation,” freedom from oppressive economic and political structures, of which zoning and environmental racism are a part.

YRL: “You hear a lot of times people talk about ‘breathing while black’ or ‘we can’t breathe,’ you know, when they are using those slogans for different––we use ‘breathing while black’ for an environmental project my students worked on as the name of the project…Kind of incorporating the Black Lives Matter movement and saying that just as police violence kind of affects people’s lives, that corporate violence, in terms of people’s health, affects people’s lives too. So he’s kinda taking it a step further to look at that.”

HOST: We’re still uncovering the effects of things that happened prior to the 1970s, when industrial corporations went relatively unchecked.

YRL: “Even if companies leave or they relocate, and they downsize, or they move down South or they move out West or they move to other countries, the damage has already been done. ….When people talk about systemic racism, and sometimes people kind of push back against that and think, ‘Well, that happened, then it doesn’t exist anymore,’ but you can still see the legacy of things that have happened, you know, centuries, decades ago.”

# MUSIC:

HOST: In other words, the fire was a symptom, not the disease—it revealed the injustices at the heart of the industrial city. And I think this particular story has resonated so deeply over time, in part, because it’s so visceral. Carl Stokes understood that. He knew that this was an opportunity to tap into that most vivid and metaphorical subject, to leverage the power of the image—fire on a polluted river in the middle of a major American city—to accelerate change.

DS: “The idea that people needed some, some visualization of the environmental crisis, that there had to be some images that they could latch onto—I think that that’s probably pretty true.”

HOST: But over the years, the mythology of the river fire eclipsed the more complex realities of life in the twentieth century—and today.

DS: “I think about the movie, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance…

HOST: It’s an old western directed by John Ford. In the film—which, by the way, came out in 1962—Jimmy Stewart plays a man who is mistakenly given credit for ridding the town of an outlaw, and he goes on to a lot of fame and notoriety. A newspaper editor learns about this, but in the end he decides not to publish the story. And he says this famous line: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

DS: “You know, when the myth becomes reality, you print the myth. And that storyline has become so strong that it really—you can’t really tell the story otherwise.”

HOST: But the catastrophe was so much bigger than the river—it was the compounding effects of disinvestment and industrialization and capitalism and environmental racism in places like Cleveland. It was about jobs and housing and civil rights and, yes, environmental pollution. It was about a system that wasn’t serving the people it claimed to serve. That’s what Stokes saw when he looked at the fire.

YRL: “If he said that, you know—people say, well, you know well it’s happened before, the river catches on fire periodically…It’s not normal for water to catch on fire, it’s wet, you know. And a lot of times people try to normalize things that are happening in, in different communities.”

HOST: So when Stokes climbed up on the charred railroad trestle that day in 1969, he became part of a much larger story of people who refuse to normalize industrial disaster–who say our communities deserve better.

YRL: “It’s been interesting to see how well some people, you know, learn about what’s going on and push relentlessly. And some of them are everyday people who never had any intention of being activists or any of that, but they just see something that they think is wrong and needs to be addressed, and they feel like, you know, somebody has to do it. So they, you know, try to rally other people to join them…And that’s kind of what it takes to get things done, you know, whether you’re a mayor or whether you’re an everyday person.”

# MUSIC

CREDITS: This episode was written and produced by me, Ryan Schnurr. Theme music by Michael Bozzo. Additional music including “Scars” by Jahzzar. Public domain recordings from the National Archives and Records Administration. Additional archival audio courtesy of the Department of Communication at UCLA. Production assistance from Cassidy Duncan. Special thanks to everyone who spoke to me for the project, as well as Anna Schnurr, Ray Fouché, Rachel Havrelock, Shannon McMullen, Sharra Vostral, Ed Simon, and Courtney Rehder.

Fire! is a production of Belt Magazine and Fortlander Media. Support for this project came from Belt readers and members, the Purdue University Department of American Studies, Jim Babcock, and the Albert LePage Center for History in the Public Interest. You can find links to sources and further reading, along with more episodes, at beltmag.com/fire.

Next time, we’ll move from Cleveland to New York City, circa 1911, to maybe the most famous American workplace fire: at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. See you then.

Ryan Schnurr is the author of In the Watershed and writer for hire covering climate, culture, infrastructure, and more. He used to edit Belt Magazine (and still writes there sometimes). He is also the creator of the forthcoming podcast series Fire!, on industrial fires and climate crisis in American cities. Ryan received his PhD and MA from Purdue University and the University of Illinois at Chicago, respectively, and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Humanities and Communication at Trine University.