“Mennonites have not been in the habit of changing details to suit the story: from our very first confessions of faith we’ve expected language to be a useful, solid bucket to hold truths as clear as water.”

By Nick Ripatrazone

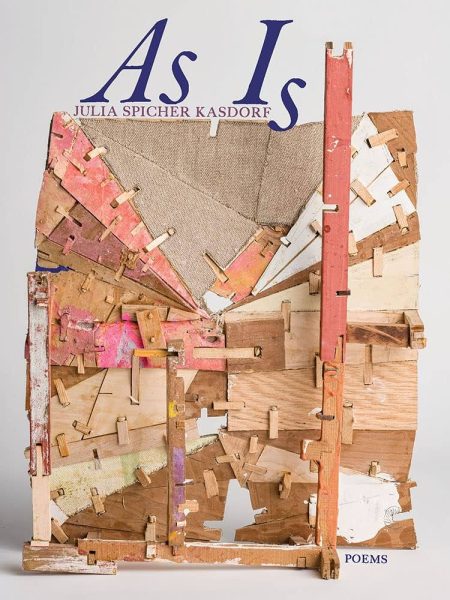

A review of As Is by Julia Spicher Kasdorf (University of Pittsburgh Press)

“War,” a poem from As Is, the fifth collection of poems by Julia Spicher Kasdorf, begins with a visiting poet who “spoke in intonations that come / from no place, peering over half-glasses” to a crowd of college students. “Queen Dido—you recall her from a high school / Latin class or maybe a Great Books course,” he notes in an aside during his reading. The references are received with silence by the students, who listen attentively, perhaps out of a sense of duty.

Seated in the front row is a “blanched local beauty with a wasp’s waist.” A poet herself, she “wrote about farm implements // rustling in morning fog, an opossum stunned / in the lane. She’d rushed to my office that day // to apologize for coming late to class—it’s that / she’d left her husband again, clothes in a trash bag.”

The narrator of “War”—a university professor—notes how the student often wrote about her husband, a wounded veteran. As depicted in her work, his actions ranged from confused (“he patrolled / hedge rows with a rifle until she hid his boots”) to violent (“she woke / to him clutching her throat.”).

The narrator ends the poem with a literary flare: “In Dido’s temple, // the frieze of Troy displayed the carnage, so / Aeneas could finally speak of the battle. No // wonder the Queen fell so hard for him before / he left Carthage, her body aflame in his wake.”

Kasdorf—the narrator, the poet—unpacks the earlier allusion made by the oblivious visiting poet. It is an interesting choice. We might wonder: how different is the speaker of the poem from the guest poet? The poem’s ending suggests that academics might view students as vehicles for their metaphors—fodder for poetic analogies, and punctuating examples. Kasdorf, a deft poet, compels us to weigh these possibilities. She wants us to look closely—an action that, truly, has been the weight of her literary project for the past forty years.

***

The first poem I ever loved was “Trout Are Moving” by Harry Humes. I read it in the Fall 2002 issue of Beloit Poetry Journal, upstairs in the Blough-Weis Library at Susquehanna University in Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania. “Past midnight they slip free / of pools and deep runs, they rise // above thistle down and meadow dew”—his lines would unfurl during track practice, while I ran off campus, along hilly runs through the Mennonite community.

Kasdorf was born in a Mennonite community in Lewistown, less than an hour from Selinsgrove, where I was truly formed as a writer—both by my professors, and the land itself. The Susquehanna River loomed; we’d run along it, and I’d also fish there. I appreciated that Humes could make the elements of my hobby seem poetic. They were poetic, of course, which is the first secret of poetry: it helps us see.

Although my cradle Catholicism is very different from Kasdorf’s Mennonite rearing, I’m drawn to her rhythms and sense. Her first chapbook, Moss Lotus, was published in 1983, but her first full-length collection appeared in 1992. Sleeping Preacher was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, which released As Is and two other books. In 1991, Kasdorf wrote an essay titled “Bringing Home the Work.” She was living in Brooklyn, and pursuing her Ph.D. at NYU, where she’d gone as an undergraduate.

Early in the essay, Kasdorf recalls how her mother would circle “inaccuracies” in her poetry manuscript. Her mother understood the genre, but was uneasy “with the blend of fact and fiction that often generates imaginative writing.” Kasdorf finds a religious origin to her mother’s vision: “Mennonites have not been in the habit of changing details to suit the story: from our very first confessions of faith we’ve expected language to be a useful, solid bucket to hold truths as clear as water.” Yet rather than distancing herself from her mother, she affirms their shared sensibility. Her mother’s “defensive reading strategy, I realized, almost parallels the way I created many of the poems in the first place.”

Kasdorf ultimately explains that the sharpest element of her identity is one of dislocation. Many of the poems in her book “were written from the perspective of an outsider—either a Mennonite outside American culture or a critical sheep in the Mennonite fold.” She concludes: “I’ve had it both ways—to be in the community and in the world—which of course means to have it neither way.”

Although Kasdorf has distanced herself from that essay—in an interview with Image more than twenty years later, she said “I am more reluctant to trace an essential connection between my background and the kind of poetry that I have written and continue to write”—her collected work demonstrates a poetics of dislocation. She is aware of herself as a poet and a Pennsylvanian; as a Christian and a feminist.

Yet perhaps most acutely, she is socially and economically aware of herself as a professor. Kasdorf has taught at Penn State since 2000. Academia anchors, and perhaps haunts, much of her poetry. The first poem in As Is, “They Call It a Strip Job,” opens with the narrator driving home “from a job where I sat in a clean, quiet room.” She moves along 219, “an old road out of West Virginia / they still call the Mason-Dixon highway” that “widens and divides at the Meyersdale bypass.” The right lane is closed due to road work, and “the scent of mud floods / in through the vents.” “All my growing up among / men who skinned hills to scrape their seams,” she recalls, but “I’ve never seen a strip job this deep or trucks this big.”

She ends the poem with a question presented as a statement: “O, how did I come / to get paid to sit in a clean, quiet room and listen // to lines written by coal miners’ grandchildren, listen / until we find the spots that smolder or sing.”

Kasdorf understandably wishes to reconsider the essay written in advance of her debut collection. Yet her poetry continually compels us to think complexly about the arc of an American poet’s life. Although Kasdorf was educated in New York City, she returned to Pennsylvania to teach, first at Messiah College in Mechanicsburg. In addition to her poetry, she has collaborated with photographers on books about her home state. Her 2018 book, Shale Play: Poems and Photographs from the Fracking Fields, was a collaboration with photographer Steven Rubin.

In her Image interview, she described that process as if she were a folklorist: “I’m really not sure what I’m doing, but my plan is to visit these places—including right around where I grew up in Westmoreland County—and listen to the ways people are talking about their experience. And to walk around, take photographs, fall in love with the landscape all over again.” Inevitably, her language arises from religion, and that religion is inextricable from Pennsylvania.

For these reasons, As Is feels suffused with an elegiac tone. Kasdorf’s own explanation of elegy is useful here: “you have to show the significance of the thing that got lost, perform the mourning, and then somehow resolve the mourning into a kind of acceptance or else you’re doomed to melancholy forever. I wonder if what you recognize as an interest in the suffering of others isn’t somehow tied up in that labor.”

One especially effective poem in the elegiac mode within the collection is “Testing.” The professor-narrator is at home: “My labors / deemed non-essential.” Each week is the “worst week until the next week comes. We lose / two thousand a day, not counting thousands // not counted.” She observes how “Priests celebrate / Easter in empty churches.” Outside, “men bob in prayer on the sidewalk, Torah scrolls / out in the sun as if they were still in the wilderness.” She laments: “I see / how invisibly some people die.”

The narrator quotes Thomas Merton’s statement that one cannot truly know hope “unless he has found how like despair / hope can be.” She ends her poem with a description of watching a woman standing in front of the “Little Free Library on our street.” The woman opens a book, reads the flap, and then reads the back cover, before replacing it in the library and pulling out another book. She repeated the mundane process, the “street light flickering on over her head.” The woman “looked / and looked until she finally left, taking nothing.”

In poems like “Testing” and even more so in “October Snow,” Kasdorf the professor fully recedes. “All afternoon it fell / onto leaves until branches,” she writes, “bent with moans or wails / or broke with gunshots.” The storm accumulates until “Ice cream softened / in its box as the town // succumbed, silent / except for the low hum / of trailer trucks hauling / freight out on route 80.”

A similar authenticity grounds “American Bittersweet.” The narrator recalls how her mother “would stop the car anywhere / to tear bittersweet from trees and fence rows, then arrange it / on the mantle.” She inspired the narrator to forage herself: “Whatever beauty we found in the woods or roadside, we took / like the shotgun shells we shoved onto our finger tips, / red and green plastic shafts with clackety brass caps.”

One of my professors at Susquehanna told me that nobody needed more help with writing than writers; that we had to find the best way to see and reveal the world without the artifice of overwrought craft. Kasdorf’s more economically and socially pointed poems are astute, yet there’s a special power to her more quiet work. Consider the gorgeous and subdued details from “Gideons”:

On Sunday afternoons back in the ‘70s, my Dad filled the car

with cartons of Bibles covered to complement motel decor:

bittersweet orange, woodgrain, ecru lake, federal blue, avocado,

and we’d drive the Lincoln Highway or Route 70, stopping

at spiked sputnik signs and parking lots besides slag heaps

or fallow fields.

Kasdorf is not that oblivious visiting poet; she is a writer sensitive to her region, steeped in her own complex identity. Some lines from her poem “Flats” best encapsulate her poetic inevitability: “Before anyone told me Persephone’s story / I endured it afternoons walking home // from the bus.” The poet precedes her education. Yet Kasdorf has encountered her social and religious paradoxes with honesty and perspicacity.

Nick Ripatrazone’s most recent books include Longing for an Absent God and Digital Communion, both from Fortress Press. He has written for Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, and The Atlantic, and is the Culture Editor for Image Journal.