Yet part of what defines Pittsburgh literature is the mystical kernel of something beyond mere matter that animates any consideration of this place: the transcendent in the prosaic, the sacred in the profane. An intimation of beauty amid a kingdom of ugliness.

By Ed Simon

The following is an excerpt from The Soul of Pittsburgh: Essays on Life, Community and History by Ed Simon and released by Arcadia Publishing.

You can’t think small in a steel mill.

—Jack Gilbert in the Paris Review (2005)

And there were so many Pittsburgh poets in my hallway that if, at that instant,

a meteorite had come smashing through my roof, there would never have been

another stanza written about rusting fathers and impotent steelworks

and the Bessemer converter of love.

—Michael Chabon, Wonder Boys (1995)

Editor John Scull’s printshop was only a few hundred yards from Market Square, where two-storied buildings were just beginning to rise along the perimeter, some constructed from the timber and brick pulled from the walls of Fort Pitt’s ruins after it was abandoned by the newly constituted Army of the United States of America in 1792. Scull had arrived in the settlement of some thousand people in 1786, when “Pittsburgh” was still pronounced in the Scottish manner rather than in the German form. The United States was only a decade old. Before it was America, Pittsburgh was in Great Britain, mostly in the colony of Pennsylvania but briefly as part of Virginia. This area was part of New France for longer than it was ever British, though for most of its history, the region was part of the Iroquois Confederacy (it still is). Like most citizens in the nascent city, Scull was not originally a Pittsburgher, having been born hundreds of miles to the east in the far larger community of Reading. Having attempted to make his career in Philadelphia, Scull decided like many others that his fortunes would be in the West. Having hauled type keys, ink and paper over the commonwealth’s mountainous divide, starting in the summer of 1786, Scull’s press would produce a four-page edition of the Pittsburgh Gazette every week, the first such publication west of the Alleghenies. Edward Park Anderson, writing in a 1931 issue of the journal Western Pennsylvania History, explains that in addition to news from Philadelphia and London, New York and Boston, the Pittsburgh Gazette also printed “local writers, who with little originality, discussed the wisdom of remaining a bachelor, the wickedness of gaming, and the virtue of women.” Scull, as the primary editor and the only printer in the city, was library, archive and salon in one simple shop. Such was the literary culture of Pittsburgh, as it existed at the time.

The two centuries hence have been more fruitful, even if national critics don’t ascribe to the Three Rivers the same literary significance that they would to the cities of the East Coast or, later, the West Coast. New York had Henry James and Edith Wharton, Boston was home to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Louisa May Alcott and urban latecomer Chicago can boast Carl Sandburg and Saul Bellow. Los Angeles may have given the world noir with Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, but when it comes to a distinctive “Pittsburgh School” of literature, such a designation seems not just a misnomer but something not even considered. This is not for lack of talent—Pittsburgh has produced or strongly influenced Willa Cather, Gertrude Stein, Thomas Bell, Rachel Carson, Kenneth Burke, James Laughlin, Robinson Jeffers, Malcolm Cowley, Edward Abbey, W.D. Snodgrass, John Edgar Wideman, Annie Dillard, Michael Chabon, Stewart O’Nan and Terrence Hayes, which isn’t even to begin grappling with the imposing theatrical monument that is August Wilson’s unparalleled Pittsburgh Cycle or contemporary prodigies like Brian Broome, Deesha Philyaw, Brian Bacharach, Ellen Litman and Damon Young. Even our two Saint Andys—Carnegie and Warhol—produced prose in the form of The Gospel of Wealth and The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again), which have their own unusual charms. Like Ireland or Czechoslovakia, Pittsburgh has produced literary wealth far beyond its relative size. Nobody less than Herman Melville would write in 1850 that “men not very much inferior to Shakespeare are this day being born on the banks of the Ohio,” but the establishment of anything that could be considered a cohesive “Pittsburgh School,” something that unites Cathar with Hayes, Carson with Bell, remains elusive. An oversight, because I’d argue that any consideration of the canon of Pittsburgh easily demonstrates a unifying thread, as diverse as the writers from this city have been, which connects all the way from Scull’s workshop to today’s Madwoman in the Attic workshops hosted by Carlow University or the readings at Bloomfield’s White Whale Bookstore.

The land of the Ohio confluence is defined by geographical liminality: neither east nor west and strung along the border between south and north. The original major metropolis was established after the United States itself, so that Pittsburgh was the first new place, the oldest new place. Unlike Boston, New York or Philadelphia, Pittsburgh was really built as an American city and not as a European city in exile. The result is that of urban literatures, Pittsburgh’s was the first to grapple with what the word American meant, and its in-between position within the country allowed itself to continue doing so over the next two centuries. If it’s been difficult to parse out a separate Pittsburgh School, then arguably it’s because the writing of the city is as synonymous with America as the city is with the nation. The writers of Pittsburgh were the first not to look toward the Atlantic and Europe but rather toward the continent and beyond, in a literature that progresses westward with the course of empire and all the brutal settler-colonialism and then industrial capitalism that would follow. That most of those with quill in hand wrote forgettable doggerel and essays about women’s chastity during the days when Fort Pitt was being disassembled doesn’t mean that all of them lacked vision, however.

On Market Street in the eighteenth century, an ink-stained Scull with calloused hands laboriously placed lead and tin key types into the press, where he would have heard haggling over produce and meat in the square’s stalls and the hawking of tinkers selling domestic wares on their way into the Ohio Territory, the brawling of drunken soldiers in the taverns, the clang of iron in blacksmith forges and the barking of dogs and squealing of pigs in the yards of his neighbors. Across the Monongahela, he would have seen miners cutting into the steep mountainside known as Coal Hill but soon to be named after the first president, the burning of this fuel coating the buildings of Pittsburgh in an eye-stinging grime and soot, the miasma of particulate mingling with the odor of offal and the smell of shit (horse and human): a pastoral land already smudged on its forehead with the mark of industry, what poet Jack Gilbert would call two centuries later a “tough heaven.”

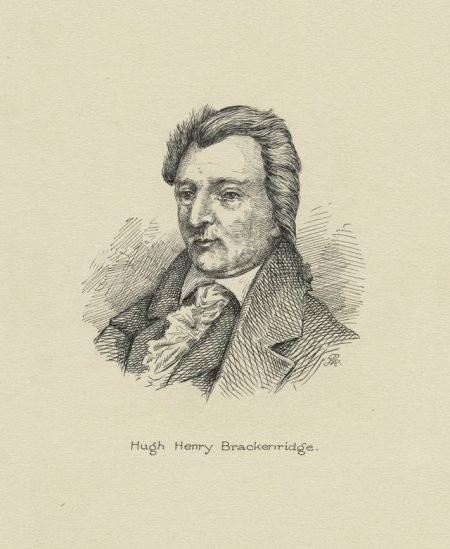

Bundled and distributed to subscribers, the Pittsburgh Gazette carried news of the Constitution’s ratification (among the first papers to print it in its entirety), of the nearby Whiskey Rebellion in 1791 and of Meriweather Lewis and William Clark’s 1803 departure from the confluence of the Ohio to points farther West. Something far more remarkable, however, than a mere newspaper, came off Scull’s press in 1792. That was the year that Scull would publish a volume penned by his fellow easterner, business partner and cofounder of the newspaper—the first edition in an ongoing serial publication by Scotsman and lawyer Hugh Henry Brackenridge titled Modern Chivalry: Containing the Adventures of Captain John Farrago and Teague O’Regan, His Servant. Like Lewis and Clark, Farrago does “ride about the world a little, with his man Teague at his heels, to see how things were going on here and there, and to observe human nature.” Brackenridge’s Modern Chivalry would be the first novel written and published in Pittsburgh. Even more remarkable, and contrary to Anderson’s contention that during the eighteenth century “Pittsburgh developed no culture of its own,” Modern Chivalry would also be the first novel published in the new republic of the United States. American literature was born in Pittsburgh.

To argue what the first American literature is remains largely an issue of semantics, of considering what regions, languages and peoples have produced such a literature, with courses in early American writing including the usual suspects like John Winthrop’s Puritan sermon “A Model of Christian Charity” and Benjamin Franklin’s thrifty autobiography and more nebulous entries based on broad New World thematic concerns, allowing Thomas More’s Utopia and William Shakespeare’s The Tempest to, rather creatively, be classified as part of our national cannon. As interesting as those debates are at the level of theory, Brackenridge’s novel is something different, a child of convenience that emerges from the definitive 1776 date of the United States’ creation—the first novel published in the new nation, as definitive a fact as can be established. The first instalment of Modern Chivalry predates by six years the 1798 gothic novel Wieland; or the Transformation by Brackenridge’s fellow Pennsylvanian the Philadelphian Charles Brockden Brown, which is frequently configured as the “first” novel in the new United States.

Pittsburgh, so often ignored by our eastern cousins, was denied the auspicious honor of the first novel in the new country from the very beginning, passed over in Philadelphia, New York and Boston before Brackenridge’s novel was yet sold. Yet while Brockden Brown’s gothic tales feel positively European, Brackenridge’s backcountry epic is a novel equivalent with the frontier. Modern Chivalry, despite borrowing from European forms, is consummately American, especially as regarding our own democratic ambivalences, with Philip Gura in Truth’s Ragged Edge: The Rise of the American Novel explaining how this narrative that takes place in Western Pennsylvania in the years after the Whiskey Rebellion is a “loose and baggy picaresque…that through satire probe[s] the country’s new social order, in particular the still-uncomfortable notion that the most plebian citizen should be afforded the same respect as a person of wealth and influence.” The United States of America, formed through the writing act itself and willed into reality through the force of an idea rather than anything else, is a uniquely literary nation, the “greatest of poems” as Walt Whitman had it. American literature is distinguished by being obsessed with defining what exactly America is (in the same way that all poetry is really about poetry) because this is a covenantal nation far more than it is a mere assemblage of people. In that way, Modern Chivalry is the first of this type. Farrago and Teague setting out on the road are Huck and Finn; they are Dean Moriarty and Sal Paradise. The subject remains the same—America.

Farrago, like his creator, is a man of contradictions: unabashedly elitist, dismissive of the poor and unlearned who compose the bulk of the settlement’s populace and yet contemptuous of the wealthy and powerful. The novel embodies the ambivalences of an author once a Federalist and then a Jeffersonian, equally of the East and of the West. Across eight hundred sprawling pages, Modern Chivalry recounts the travels of aristocratic and rational Farrago, the Don Quixote of the tale, with his Sancho Panza in the form of comedic and foolish Teague (a Scotts Presbyterian, Brackenridge is as generous in his depiction of the Irish Catholic O’Regan as can be expected). Doing in fiction what De Tocqueville would accomplish with his travelogue Democracy in America some years later, Modern Chivalry episodically recounts Farrago and O’Regan’s interactions with the commonfolk between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Brackenridge’s characteristic border-country skepticism of central authority—so Scottish and Appalachian—is obvious in the novel. “You have nothing but your character, Teague, in a new country to depend on,” Farrago says to his manservant after the latter is somehow elected to Congress. “Let it never be said, that you quitted an honest livelihood, the taking care of my horse, to follow the newfangled whims of the time, and to be a statesman.” Class divisions, ever an American problem, ever a Pittsburgh one, were visible to anxious Brackenridge, who despite being a gentleman lived not more than a minute from the city’s poorest inhabitants in a settlement so small. The author’s sentiments were often as contradictory as Farrago’s were, with Cathy Davidson writing in Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America that Brackenridge was a “curious combination of elitist and plebian, of Princeton-educated classicist and backwoods lawyer,” a man who “frequently appeared in court rumpled and dirty, his hair unkempt, without socks, and, more than once, without shoes.” This was a gentleman who not only wrote the first American novel and cofounded the city’s first newspaper but also established the institution that would one day grow into the University of Pittsburgh. Brackenridge, the lawyer who during a rainstorm wished to avoid getting the single suit he owned wet so he rather elected to ride his horse through Pittsburgh in the nude, because “the storm, you know, would spoil the clothes, but it couldn’t spoil me.” If Pittsburgh writers are anything, it’s against pretension.

Imagining Brackenridge as the spiritual godfather of the literature of the United States is perhaps an issue of simple chronology, but to posit him as a uniquely Pittsburgh author is arguably more critical conceit than demonstrable reality. Categorizing Modern Chivalry as proletarian literature would be fallacious, though Brackenridge did have opprobrium “reserved for rich land speculators who…exploited the penury of others and profited at the expense of the whole nation,” as Davidson writes. This was combined with the skeptical wisdom wherein Brackenridge holds that the “demagogue is the first great destroyer of the constitution by deceiving the people. He is no democrat that deceiveth the people. He is an aristocrat.” Anti-pretension is maybe just the softer form of the radical qualities we associate with the proletarian novel, and the Pittsburgh School has, as material conditions necessitate within the industrial city, always had an intimate relationship to the physicality of work and an allergy to unearned ethereality. This is, after all, a hard paradise of kiln and forge, mill and factory.

Still, I’d argue that all the major concerns of Modern Chivalry’s creator are explicit in the school that would come to develop afterward, even if Wilson and Dillard weren’t sitting with copies of that eighteenth-century novel open in front of them. What Brackenridge, Wilson, Dillard and every other potential member of the Pittsburgh School happen to share is a concern with materiality and with the sublime attributes of landscape and the industrial labor that was facilitated by that landscape. Furthermore, and in the truest honor of those conflicted and conflicting subjects, such writing is always about America, since anything that fully expresses Pittsburgh must also completely interrogate the nation of which it is a part. The United States of Ambivalence, a nation both Eden and Babylon, Genesis and Armageddon, supposedly of unlimited promise but also defined by the filthy and cruel manner in which said promise is fulfilled. “Nature is here in her bloom; no decay or decrepitude,” wrote Brackenridge, considering the mountain streams flowing into the Monongahela and the Allegheny, the verdant spring along the Appalachians. “All fragrancy, health, and vivacity,” but Paradise still remains workable land, after all. Brackenridge writes that the men of Pittsburgh must be workers in “iron and in leather, and in wood. Invention, as well as industry, must be requisite.” And so it was.

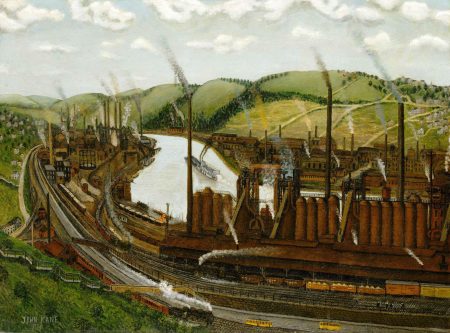

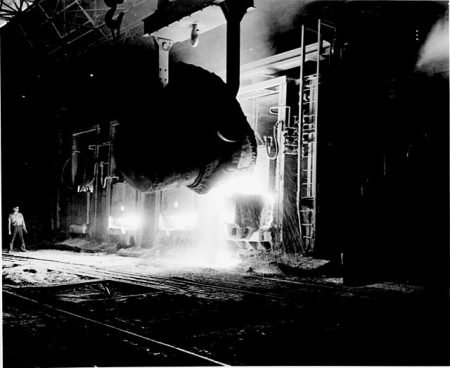

Thomas Bell’s (née Adalbert Thomas Belejcak) proletarian masterpiece, the 1941 novel Out of This Furnace: A Novel of Immigrant Labor, bears little similarity at the surface level to Modern Chivalry—the latter with its chauvinistic extolling of Anglo-Saxon values as pioneers set out on the Western frontier and the former about the experience of degradation, exploitation and poverty among the immigrants who worked in steel mills owned and operated by the proverbial great-great-grandchildren of a man like Brackenridge—yet both books share the Pittsburgh School’s perseveration on industry and physicality, with the paradox of finding a heaven in a hell. A sprawling family epic, Out of This Furnace begins with the arrival of Slovakian immigrant Djuro Kracha in Braddock, where he works at the (still extant) Edgar Thomson Steelworks. The narrative follows his daughter Mary and her husband, Mike Dobrejcak, who also labors within the mills, and finally concludes with the third generation, when their son Dobie Dobrejcak agitates on behalf of a successful union organization effort. Evoking the great working-class novels of the first half of the twentieth century, such as Tillie Olsen’s 1930s Yonnondio: From the Thirties and Pietro Di Donato’s 1939 Christ in Concrete, Bell’s novel is concerned with the “acculturation and evolving political consciousness of the immigrant workers of America’s steel towns,” as David Demarest matter-of-factly explains in his afterword to the 1976 reprint. Bell bluntly stated in a 1946 interview with the ethnic Lemka newspaper Ludovy dennik that “I saw a people brought here by steel magnates from the old country and exploited, ridiculed, and oppressed,” and indeed the novel itself is in part a defense of the maligned “mill hunkie,” the Eastern European laboring class that constituted the bulk of workers during these decades.

Only a few miles to the east of Pittsburgh, Braddock is a representative Western Pennsylvania mill town: the hulking golem of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works rusting by the banks of the Monongahela, hundreds of thousands of immigrant men laboring on behalf of first Carnegie Steel and then U.S. Steel in unimaginably dangerous conditions. Braddock, Pennsylvania, is the literal setting of Out From This Furnace, but as Bell well knew, there were many Braddocks—in Connellsville and Homestead, McKeesport and Tarentum. In Pittsburgh, too. Working in a mill, especially in the decades before widespread labor organization ensured a basic degree of safety precautions, which were further strengthened by federal regulations, was a dangerous means of employment. Men frequently incurred horrible injuries at places like Edgar Thomson, Homestead Steel Works or Jones and Laughlin. Men died from exposure, from being crushed, by being burnt. This isn’t even to consider the sorts of ways that such physical labor can break down the body itself over the course of decades: the strained muscles and calloused flesh, the sprained backs and slipped discs. Out From This Furnace concerns itself with physicality in this intimate sort of way; it’s materialist in its broadly Marxian politics, but more than as a method of analysis, matter is the realm in which his characters are forced to operate, the undeniable reality of not just capital and labor but of molten steel as well (and what that liquid metal can do to a human body).

Yet part of what defines the Pittsburgh School, from Brackenridge onward, is the mystical kernel of something beyond mere matter that animates any consideration of this place: the transcendent in the prosaic, the sacred in the profane. An intimation of beauty amid a kingdom of ugliness. “Looking up,” Bell writes, one can see the “furnaces and stoves, piled one behind the other into the distance, small lights, and over beyond the rail mill the wavering glow of the Bessemers. A steel mill at night made a man feel small as he trudged into its pile of structures, its shadows.” Certainly Pittsburgh literature isn’t the only body of writing that can examine the cracked beauty of the rusted, hulking material world, of the utopian hid within the grimiest of places, but it’s the overwhelming obsession of all prose and poetry that is indelibly marked by the Steel City, the wisdom that comes from the sublimity of industry. “A cast-house filled…with illumination as the furnace was tapped and the bright glare of the molten metal was like a conflagration around the end of an alleyway, silhouetting waiting ladles, the corner of an engine house, skeleton beams.”

Bell’s grandparents came to America from Slovakia, but the ancestors of John Edgar Wideman arrived in America on a very different boat, and that, as is always the case in America, makes an important difference. He was descended from enslaved African Americans on both sides of his family—his mother’s people were from Maryland and his father’s from South Carolina—and the family was part of the Great Migration northward from the states of the former Confederacy to cities like Pittsburgh. If Wilson had the Hill, then Wideman has Homewood, his trilogy of books about that Black neighborhood in Pittsburgh’s east end describes a community as evocative as James Joyce’s Dublin or William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Wideman’s prodigious literary output is strongly marked by the difficult contradictions of American life; he is the Rhodes Scholar who attended the University of Pennsylvania on an academic scholarship, was foundational in the creation of African American studies as a discipline at his alma mater and was a two-time winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award, while his brother and son were both convicted in two separate murder trials. In experimental, incandescent prose across novels, short stories and memoir, Wideman explores these contingencies of race and trauma in works like The Lynchers, Reuben, Philadelphia Fire, The Cattle Killing, Two Cities and Brothers and Keepers, but it is arguably the Homewood Trilogy for which he will be most valorized. Though Wideman’s novels range over the globe, across America, Europe and Africa, it is the working-class Black neighborhood of his youth that provides a geography of the soul. Even though the narratively interconnected works were never intended to be written as a trilogy, the 1981 short story collection Damballah, the novel Hiding Place from that same year and the novel Sent For You Yesterday from 1983, have been published as an omnibus since 1985, editors seeing the subconscious connections that aren’t always intentional. What Wideman presents in these three works is an alternate mythogeography of the American experience relying on the aesthetics of the author’s home city in its expression of the paradoxes of beauty and ugliness that define existence in Pittsburgh.

As a series of short stories, Damballah—named after the serpentine demiurge who creates the world in the complex mythological system of West African and Caribbean Voudon—presents an alternate history of Homewood, Pittsburgh and the United States, for as Walton Muyumba writes in his foreword to the career-spanning collection You Made Me Love You: Selected Stories, 1981–2018, “Wideman’s art is rooted in Homewood’s idiom thus; it rises from the blues aesthetic tradition and speaks universally,” rhetorically placing the author in a lineage of Pittsburgh jazz musicians that includes Billy Strayhorn, Mary Lou Williams, Art Blakey, Ahmad Jamal and Billy Eckstine. Like a jazz musician improvising a theme, Damballah draws from both invention and family folklore, crafting a creation myth for the neighborhood. Presented as a letter between an unnamed narrator writing on an idyllic Greek isle to his brother in prison, Wideman’s story claims that Homewood was founded the year before Ft. Sumter by their great-great-great-grandmother, the oracularly named Sybil Owens, who escaped from slavery in Cumberland, Maryland. “I heard her laugher, her amens, and can I get a witness, her digressions, the web she spins and brushes away with her hands,” writes Wideman. “What seems to ramble begins to cohere when the listener understands the process, understands the voice seeks to recover everything, that the voice proclaims nothing is lost,” or as one of the author’s favorite aphorisms has it, “All stories are true.” As is the nature, purpose and utility of creation myths, Wideman’s story “The Beginning of Homewood” shouldn’t be read as a literal or historical account of the neighborhood’s origins but rather as a riff on how we generate meaning out of the stories we tell. History, as a nightmare to which we’re ever waking, can’t quite be escaped in Wideman’s works, but there can be shards of luminescence despite the darkness. Homewood, in the author’s descriptions, is a tough place, an ugly place. “Somebody should make a deep ditch out of Homewood Avenue…and just go and push the rowhouses and boarded storefronts into the hole. Bury it all.” And yet, as is ever true of the metaphysics of the Pittsburgh School, there is a temporary utopia oft in the moment, where even the names of “streets can open like the gates of a great city, everyone who’s ever inhabited that city, walked its streets, suddenly, like a shimmer, like the first notes of a Monk solo, breathing, moving, a world quickens as the gates swing apart.”

House in the Point Breeze neighborhood of Pittsburgh

By distance, Annie Dillard’s Pittsburgh was preposterously close to that of Wideman’s, the neighborhoods of the former’s wealthy Point Breeze and the latter’s impoverished Homewood separated by only a few blocks, Penn Avenue functioning as a spiritual boundary between the two. On one side were ivy-covered, granite-stoned Tudor homes, on the other long lines of broken brick rowhouses. Frequently categorized as a nature writer —a not incorrect though arguably incomplete designation—Dillard is an author of lyrical nonfiction as in her 1974 Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and 1982 Teaching a Stone to Talk conceive of the environment through a distinctly Christian understanding, yet she is aware that the world is always mediated through human perspective (and often human intervention). Hers is a nature that is somehow both Darwinian and endowed with meaning, where following the “one extravagant gesture of creation in the first place, the universe has continued to deal exclusively in extravagances, flinging intricacies and colossi down aeons of emptiness, heaping profusions on profligacies with ever-fresh vigor. The whole world has been on fire from the word go,” as she writes in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. “But everywhere I look I see fires; that which isn’t flint is tinder, and the whole world sparks and flames.”

Like Bell’s colossal steel mill or Wideman’s streets metaphorically thrumming with the sound of Thelonious Sphere Monk, Dillard’s world is endowed with tongues of fire. In her 1985 memoir An American Childhood, Dillard refers to her childhood neighborhood as the “Valley of the Kings,” comparing this abode where once Carnegie, Frick, Westinghouse and Heinz built their palatial estates to the Pharaonic Necropolis of ancient Egypt. By the time of her youth in the ’50s, the area was solidly upper middle class (her father was an oil executive, and she attended the exclusive Ellis School), yet the remnants of its much more opulent Gilded Age past still marked Point Breeze. Evidence of the tremendous wealth that shaped the city was everywhere, in robber baron mansions subdivided into apartments and the wrought-iron gate that used to be H.J. Heinz’s fence running alongside blocks of Penn Avenue only a few minutes from Wideman’s Homewood. Pittsburgh was built on top of itself, its history waiting to be excavated as it were that actual Valley of the Kings. This setting helped to develop Dillard’s gift for sensory detail, which she has honed into an almost theological precision. In her memoir, Dillard recounts how when she officially left the Presbyterian Church as an adolescent, the minister told her that she would be back, and in many ways he was correct (if not in the way he intended).

Her prose (which has more than a bit of the poetic about it) adopted the sacramental poetics of a Gerard Manley Hopkins or a William Blake with awareness that the world is simultaneously fallen and enchanted with a charged energy. As she writes, “Skin was earth; it was soil. I could see, even on my own skin, the joined trapezoids of dust specks God had wetted and stuck with his spit the morning he made Adam from dirt. Now, all these generations later, we people could still see on our skin the inherited prints of the dust specks of Eden.” Within Dillard’s writing, there is this perseveration on the possibility of transcendence in the mundane and for the sacred in the profane, that overweening concern of the Pittsburgh School. Dillard may be most celebrated for bringing this awareness to her observations of the natural world in rural Virginia, but it was a spiritual skill inculcated by the contradictions of Pittsburgh, where rusting mills abut massive parks. That environment was her first tutor in the personal vocabulary of matter and spirit. Indeed, the first few pages of An American Childhood provide a sterling example of the Pittsburgh School’s fascination with materiality and the way in which certain immanent enchantments can be implied by nature.

Until recently, Pittsburgh had a grim reputation in the national media, the stereotypes of the smoggy, smoky city that appeared as a “hell with the lid off,” in the memorable description of the Atlantic Monthly correspondent James Parton in 1868. In such portrayals, the fact is often occluded that this is a place that is incandescently beautiful. The Pittsburgh School is enmeshed in the physicality of place not just because of industry but because the terrain and topography of the city is so shockingly dramatic, so astounding, so otherworldly. “When everything else has gone from my brain,” writes Dillard at the beginning of An American Childhood, “when all this has dissolved, what will be left, I believe, is topology: the dreaming memory of land as it lay this way and that.” Pittsburgh literature uses abstraction, but it is not a literature of abstraction. It is very much centered in place: in the hills, rivers, mountains and valleys, in the earth itself. From the dross material of place then comes forth the ethereality of transcendence. In Pittsburgh, abstraction is the child of the concrete and not the other way around.

“I will see the city poured rolling down the mountain valleys like slag, and see the city lights sprinkled and curved around the hills’ curves, rows of bonfires winding,” writes Dillard. “At sunset a red light like housefires shines from the narrow hillside windows; the houses’ bricks burn like glowing coals.” Note how she elevates the vocabulary of industry—slag, glowing coals—and transmutes them into the landscape; a transubstantiation of grit into gold, marked by a scriptural parallelism. “The tall buildings rise lighted to their tips. Their lights illumine other buildings’ clean sides, and illumine the narrow city canyons below,” as Dillard describes the totemistic beauty of the Golden Triangle, the spangled tableau that announces itself to visitors as they depart from the Fort Pitt Tunnel over Downtown Pittsburgh at the confluence of the Three Rivers. And as Dillard knows, the human creations of beauty are only ever borrowed from the earth, which is simultaneously exploited and loved by civilization but, regardless, will always be that which is victorious. “When the shining city, too, fades,” in eons hence, what will remain are those “forested mountains and hills, and the way the rivers lie flat and moving, among them, and the way the low land lies wooden among them, and the blunt mountains rise in darkness from the rivers’ banks, steep from the rugged south and rolling from the north.”

Any good materialist knows that culture builds itself on the physical world; in the tough heaven of Pittsburgh, denial of that basic axiom is an impossibility. The poetics of Pittsburgh—if we can speak of such a thing—provide an additional gloss to that axiom in the form of the foolish wisdom that comprehends that materiality pushed to its extreme doesn’t just allow for the spiritual but demands it, that sees something revolutionary in the transcendent, the ecstatic, the mystical. This is the beautiful surrealism of Michael Chabon’s The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, where the concrete and iron power station in the ravine of Panther Hollow between the Carnegie Museum and Carnegie Mellon University is a “cloud factory,” where in Pittsburgh the “sky glowed and flashed orange, off toward the mills in the south, as if volcano gods were fighting there or, it seemed to me, as if the end of the world had begun; it was an orange so tortured and final.”

This, then, is the fullest summation of the Pittsburgh’s School’s central aesthetic: not that it’s concerned only with being blue collar and working class, or that it’s all about industry, or even the landscape (though it is about all of those things) but that it deigns to acknowledge the sacredness hidden within an old brick building, a rusting foundry, a litter-strewn river bank. That it’s a variety of writing that fundamentally says yes to the numinous, yes to the holy, yes to the beautiful, not in spite of those things being hard to perceive but precisely because they are so often hidden. “Pittsburgh persists in being existentially itself,” writes poet Samuel Hazo in his 1986 essay “The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You.” “It simply but inevitably and determinedly keeps becoming what it is,” and this is the subtle ingredient that defines a specific poetics of Pittsburgh.

Furthermore, this is the indelible effect that Pittsburgh has on those of us from here, especially for those of us who are only able to make sense of things through that imperfect medium of words, because as natives to this beautiful and cursed land we are never able to leave and always determined to come back. What Jan Beatty describes in her 2017 collection Jackknife: New and Selected Poems when she writes of being “filled with sediment: / with tough, dirty Pittsburgh / where the mountains of black rock & / half mills are carapaces” or Patricia Dobler’s sense in her 1986 Talking to Strangers about how “the sun rose in sulphur / piercing the company house” so that our “soft bones eaten with flesh…tempered the heart of the eater.” Steel City aesthetics are all about contrast or maybe, more appropriately, paradox, for it’s not that the city is tough and beautiful but rather that heaven itself should look like Pittsburgh. Judith Vollmer in her 1998 The Door Open to the Fire looks out from Mount Washington, toward the direction where Scull once printed his newspaper, and she claims that “under fog that falls…Pittsburgh stands in for Paris, San Francisco, / even a minor, gritty Rome,” while Joseph Bathanti, now the poet laureate of North Carolina but a Pittsburgher originally, writes in Sun Magazine that we can expect that in the hereafter “angels from the ether / bear platters of ravioli / from Groceria Italiano / in Bloomfield; sausage / from Joe Grasso on Larimer Avenue; / lemon ice from Moio’s; / sfogliatelles from Barsotti; / Parmesan, aged for eternity.”

In my experience, the only people who hate Pittsburgh are those who’ve never come here or those who’ve never left. There is a hard-worn wisdom within this terrain and in being able to compare it to elsewhere. Pittsburgh writers don’t deny the materiality of our circumstances, so that when ethereality arrives, it’s as a difficult grace. Tough heaven, indeed. Gerald Stern, poet laureate of New Jersey but fundamentally always of Pittsburgh, the Allderdice graduate from Squirrel Hill, writes in one of his most famous lyrics from 1984’s This Time: New and Selected Poems about his family learning of the end of World War II in that “tiny living room / on Beechwood Boulevard.” Millions of Stern’s fellow Jews burned in the ovens of Hitler, so much more hideous than the furnaces of Pennsylvania, but despite such evil, the poet and his family dance joyfully at the end of the war, “my hair all streaming, / my mother red with laughter, / my father cupping / his left hand under his armpit, doing the dance / of old Ukraine.” This is a wisdom that sees genesis in every apocalypse, that understands the presence of God among “wrinkled ties and baseball trophies and coffee pots.” They aren’t in Poland or Germany, but from five thousand miles away, the Sterns genuflect before the “God of mercy…wild God.” He describes the “three of us whirling and singing, the three of us / screaming and falling…as if we could never stop,” even here in the “home / of the evil Mellons,” in “Pittsburgh, beautiful filthy Pittsburgh.” It’s a spiritual truth of the Pittsburgh School, this understanding that filth and beauty aren’t in contradiction but rather they justify themselves and each other —a truth of the great patriarchs and prophets, a scriptural truth. Stern’s friend Jack Gilbert, with whom he would drunkenly traipse through the streets of East Liberty, understood Pittsburgh similarly. “The rusting mills sprawled gigantically / along three rivers. The authority of them,” writes Gilbert in Tough Heaven: Poems of Pittsburgh. The “gritty alleys where we played every evening were / stained pink by the inferno always surging in the sky, / as though Christ and the Father were still fashioning / the Earth.” What Pittsburgh represents, for Gilbert, is a place embodying the principle of the “beauty forcing us as much as harshness.” Here, then, are the poetics of Pittsburgh—the way the low winter light strikes grey slag along the banks of the Monongahela, a chipped plaster statue of the blue-robed Virgin Mary encircled in a buried porcelain tub on a browning Greenfield lawn, a daisy pushing through cracked Bloomfield concrete, the low glide of a peregrine falcon as it launches itself from the towers of Oakland. On earth as it is in Pittsburgh.

Banner image courtesy of painter Ron Donoughe.

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine.