Today’s generation of Appalachian writers has been able to find outlets for an array of work that delves deep into the complexities and nuances of a geographic region larger than many nations in both area and population.

By Christina Fisanick and Damian Dressick

Words we never thought we’d write: Appalachia is hip. That’s right, from The New York Times to Netflix and everywhere in between, people and pundits are talking about Appalachia. While some of this newfound interest in Appalachia may be in response to the shameless and self-interested purveyance of well-worn stereotypes by one ethically-bereft Ohioan, the recent resurgence in Appalachian literature is comprised of so much more than mere clapbacks.

Today’s generation of Appalachian writers has been able to find outlets for an array of work that delves deep into the complexities and nuances of a geographic region larger than many nations in both area and population. Barbara Kingsolver’s most recent novel, Demon Copperhead, for example, is an Appalachian spin on Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. The novel has been widely acclaimed by readers both in and out of the region for its brilliant storytelling and realistic depiction of Appalachia and Appalachians. While Kingsolver could have easily slid into hoary tropes, she chose to portray her truth of the region and its people.

But even Kingsolver forgets or resists that Northern Appalachian writers are responsible for some of the region’s most lasting and powerful literature. Following our reading of Kingsolver’s article “Read Your Way Through Appalachia” in the August 9 issue of The New York Times, we wrote a response we felt summed up our decades-long frustration as Northern Appalachians being Othered in a community of Others. Our response to Kingsolver appeared in the Sunday, September 24 issue of The New York Times Book Review. The feedback we received and still are receiving has come from writers and readers all over the country who agree with our concern that once again, Northern Appalachian writers have been forgotten, or, in this case, neglected, and by someone from the region no less.

Our primary issue with Kingsolver and most other catalogs of Appalachian literature is that her list of luminaries offered included few writers from Northern Appalachia. Acknowledging that no list of this kind can ever be complete, those of us who read Demon Copperhead were hopeful when we opened The Times that morning that we would find ourselves and our literary heroes mentioned. While we were pleased to see Martins Ferry, Ohio, poet James Wright, for example, we felt the absence of other notable texts to be frustrating and exclusionary.

This article, then, is our attempt at helping Northern Appalachians and others develop an understanding of where and what constitutes Northern Appalachia, how it might differ from other parts of the Appalachian region, and perhaps most importantly, to take a stab at assembling what we hope is the beginning of a primer of Northern Appalachian literature. We know our list will be far from exhaustive, but we hope that our experiences as scholars focused on Northern Appalachian literature, editors of the journal Appalachian Lit, and hosts of WANA LIVE!: The Reading Series of Writers Association Northern Appalachia have presented us with opportunities to discover and appreciate a host of writers and writing from all over Northern Appalachia. We aim for our work to serve as the catalyst for a conversation that will expand understanding of the literature of the northern part of the region and Appalachia in general. If we left out one of your favorites, let us know!

Mapping Northern Appalachia

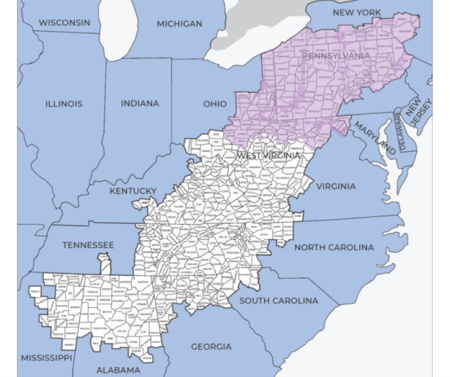

Appalachia is a conspicuously large region. Using the map established by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), the region stretches from Mississippi to southern New York and includes 423 counties! While there is considerable debate about the hows and whys of this understanding of Appalachia, it represents a good place to start in considering who and what can be considered Appalachian. We, as the president and vice-president of WANA, would suggest that northern Appalachia looks somewhat like this:

We make this argument knowing that we may be courting controversy, but we believe Northern Appalachia is home to writers who share a common culture that overlaps with, but is inherently distinct, from Central and Southern Appalachia. Our ancestors, too, worked in coal mines and broke their backs farming their land, but they also labored in steel mills and glass factories. While Northern Appalachia possesses no shortage of the descendants of English, Scotch, and Irish, our region is also heavily populated by eastern and southern European immigrants. Poles, Italians, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Greeks, Magyars, Croats, and others established strong communities in the coal patch towns that dotted the Northern Appalachian foothills and built the steel cities that grew in our river valleys. Religion, too, provides a contrast with Southern and Central Appalachia. Our cities, towns, and villages may have their share of Baptist and Pentecostal churches, but Catholic and Greek Orthodox congregations often predominate.

Our topography represents yet another arena of both similarity and difference. While the eroded Allegheny Plateau may offer similar breathtaking vistas and contribute in a similar way to a particular brand of social organization, the rural landscape of Northern Appalachia is broken by urban centers that create possibilities and problems that do not exist in areas of Appalachia that are largely rural. In examining our region’s history, it is also important to note that Wheeling and Pittsburgh both served not only as population centers which accumulated both capital and industry but functioned as gateways to the West for both explorers and settlers. This sense of transience and amalgamation stands in stark relief to the smaller settled-for-generations communities of the south and central parts of the region. Given these large-scale differences, it makes sense that northern Appalachian writers encountering what we were told is Appalachian literature sometimes struggle to find portrayals of our own people, places, and traditions. We want to change that.

The Northern Appalachian Literary Tradition

We believe that if Northern Appalachian writers were more aware of the region’s literary tradition most of us would not feel so alone as writers, particularly as young people first starting to understand ourselves as individuals inclined to make meaning out of imagination and language. Most northern Appalachian writers with whom we have spoken, while finding much to admire in texts from the cannon of Appalachian literature–books like Wilma Dykeman’s The Tall Woman and Kathryn Stripling Byer’s Wildwood Flower–see little that resembles their own lived experience. So then, just what books *are* ours?

Noted Eastern Ohio poet Richard Hague addressed this issue at the 2021 Writers Association of Northern Appalachia Conference. He spoke eloquently of our literary heritage, weaving the Northern Appalachian literary tradition into the greater canon of Appalachian literature. For attendees, this presented an opportunity to both consider our writerly lineage and envision a roadmap to our collective literary future.

Following Dick’s speech, we set about tracing our written roots back to their beginnings. We learned about speeches given by Cornstalk advocating for reduced conflict during the French and Killbuck’s efforts to give voice to concerns about British imperialism. We saw how Northern Appalachian voices were instrumental in building our nation. Writers like Ann Newport Royall and Tom the Tinker spoke out against early political injustices, like political corruption and unfair taxes imposed on Pennsylvania farmers. Folklorists like Ruth Ann Musick and Henry Shoemaker preserved our unwritten cultural traditions by collecting and transcribing shared oral stories from old wives’ tales to ghost stories.

By the mid-1800s abolitionist discourse dominated our literary landscape. Journalists like Jane Gray Swisshelm penned numerous articles in the fight for emancipation. Later, as the United States joined the industrial revolution, writers in Northern Appalachia gave birth to an entire genre. Rebecca Harding Davis, and later, William Dean Howells, created American literary realism, a genre that continues to flourish in northern Appalachian and throughout American letters.

The turn of the twentieth century gave rise to pro-union voices. Milltown classics like Thomas Bell’s Out of this Furnace presented our nation with a portrait of life in its gritty and growing industrial cities. Writers like Willa Cather and Sherwood Anderson brought our region’s residents to life in short stories, while journalists like Nellie Bly advocated for women’s rights. As the country reeled in World War II privation and reveled in post-war prosperity, Rachel Carson and Davis Grubb illuminated the shortcomings of the American dream and its toll on the environment and smalltown life. During this era, acclaimed poets Stanely Plumly and James Wright worked to explore the complicated relationship between nostalgia for the past and reality.

As all booms inevitably do, the post-war industrial boom went bust, and in Northern Appalachia this began with the demise of the coal and steel industry in the 1970s and 80s. Writers in the Rust Belt—much of which overlaps with northern Appalachia—preserved factory culture and its demise in poetry by Rick Campbell and Timothy Russell, literary nonfiction by Larry Smith, and fiction by John Edgar Wideman. Chuck Kinder, Cynthia Rylant, and others worked to capture life off the beaten path. In addition, this era saw the rise of Northern Appalachia’s most acclaimed playwright, August Wilson.

As Northern Appalachian writers endured these decades of economic decline, the rest of Appalachia experienced the kind of literary renaissance which would not come to the north until the turn of the twenty-first century. Thankfully, when the renaissance did arrive in the north, it ushered in an era of writing that is both nationally known and diverse. From Jennifer Haigh and Tawni O’Dell to Carter Sickels and beyond, contemporary northern Appalachian fiction gives voice to the region’s past and present. Literary nonfiction written by Neema Avashia, Scott McClanahan, and Matt Ferrence challenge long-held national perceptions of Appalachia and Appalachians. Poets like Marc Harshman, Maggie Anderson, Ross Gay, and Gerry LaFemina weave lyrical portraits of life above the Mason-Dixon Line.

Many of these contemporary works, such as Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies and Donald Ray Pollock’s The Devil All the Time, have been optioned by filmmakers and streaming services, like Netflix, bringing our literary culture and imagination to audiences beyond our geographic borders.

And, of course, we cannot forget the literary powerhouse that is the Pittsburgh writing scene. Known as the Paris of Appalachia thanks to Brian O’Neill, it is the largest city in all of Appalachia and an incubator for some of northern Appalachia’s best writing through graduate writing programs at institutions like the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University, Chatham University and Carlow University, and groups like Madwomen in the Attic. Names that read like a “who’s who” of contemporary American literature can be found writing in Pittsburgh: Jan Beatty, Judith Vollmer, Ed Simon, Terrance Hayes, Brian Broome, Yona Harvey, Toi Derricott, Jim Daniels, Lynn Emanuel, Lori Jakiela, Sherry Flick, Shelia Squillante, Joseph Bathanti, the late David McCullough, Damon Young, Stewart O’Nan, Kathleen George, and Anjali Sachdeva.

While fully aware that we likely left out one or more of your favorites from this list (we didn’t even include everyone on our list), we hope to have ignited a conversation about Northern Appalachian literature that will continue to grow as other readers and writers join. We remember as young writers the confusion we felt in learning that we were Appalachian and yet not finding ourselves and our people in what was then the cannon of Appalachian literature. Our intention is to give current and future writers a literary home in a world populated by people, places, and things we call ours, and to let the rest of the country and world know, “We are here! We are here!”

A Short Bibliography of Recommended Works