By Vince Guerrieri

In July 2013, 95 years after it opened, downtown Youngstown’s Paramount Theater put on its last show. The Paramount (originally dubbed the Liberty) opened as a vaudeville and live theater venue, at the corner of West Federal and Hazel in 1918. In 1929, back when film studios operated their own theater chains, the Liberty was bought and renamed by Paramount Pictures, and modified to show movies.

But that final show in the summer of 2013 wasn’t on the screen inside the Paramount. Small groups of downtown office workers and wellwishers old enough to remember the theater as a theater milled around outside the Paramount, watching it come down.In Youngstown’s heyday, West Federal Street was the commercial center of the city and the site of three grand movie houses. A fourth theater, the Palace, was a block away on Commerce Street. But only one of Youngtown’s grand theaters has survived.

A much larger crowd had gathered at the corner of West Federal and Chestnut on April 16, 1931, for the invitation-only grand opening of the Warner Theater. The Millionaire, the Warner’s first movie, played to a capacity house of 2,500. Another 1,000 people showed up just to stand outside and rubberneck at the spectacle of the premiere.

The Liberty/Paramount Theatre in 2012, less than a year before its demolition. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The theater was designed by Rapp and Rapp, a company that specialized in building movie palaces. Among Rapp’s other creations were the Chicago Theater in its namesake city, the opulent Michigan Theater in Detroit—built on the site of a garage where a young tinkerer named Henry Ford built his first motorized quadricycle—and the Palace Theater in downtown Cleveland.

The female attendees wore furs. Their escorts wore tails and boiled shirts. Mayor Joseph Heffernan gave a stem-winding speech about how the theater represented everything great about Youngstown. “Everything in New York is coming to Youngstown but Grant’s Tomb and the aquarium,” he said.

[blocktext align=”left”]The female attendees wore furs. Their escorts wore tails and boiled shirts. Mayor Joseph Heffernan gave a stem-winding speech about how the theater represented everything great about Youngstown.[/blocktext]When the Warner opened, Youngstown was a boom town. The city’s population had swelled to more than 170,000 as the steel industry, launched in 1900 with the incorporation of Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube, thrived. By 1930, Youngstown Sheet and Tube (the word “iron” had since been dropped) was the largest corporation headquartered in the state of Ohio, taking up five stories of the Stambaugh Building, across the city square from the Palace.

Between 1900 and 1920, the city’s population had tripled from 40,000 to 120,000. Immigrants from across Southern and Eastern Europe arrived to work in the mills and factories that popped up throughout the city. 80 percent of the 1920 population were immigrants or first-generation Americans.

Among those immigrants were a Polish shoemaker named Samuel Wonsal (or Wonskolaser, depending on the source), his wife

Pearl, and their children. Sam anglicized the family name to Warner, and his 11 children included four sons: Polish-born Harry (born Hirsch), Albert (born Abraham), Sam (born Schmuel), and Jack (born Jacob), who was born in Canada. The Warner brothers quickly saw the potential in the infant motion-picture business. The brothers began putting on screenings in the Youngstown area, at both the city’s old downtown opera house and Idora Park, the amusement park opened in 1899 on the city’s South Side.

The Warners built their first theater over the state line in New Castle, Pa. Ultimately, they went to California to open up a film distribution company, and started making their own movies. Out west, the immigrant boys from Youngstown found themselves on the outside looking in at the three major Hollywood studios of Paramount, Universal, and First National.

But in 1926, the Warners released the first feature film with sound, Don Juan. Previously, any musical accompaniment for a film had to come from live musicians in the theater. But the 111-minute Don Juan boasted a synchronized musical score and sound effects. The technological advance was well-received, and the Warners set to work on the first talking movie, which would be produced by Sam Warner. The Jazz Singer premiered in 1927, changing the movie industry. Sam Warner didn’t live to see it. He died of pneumonia the day before the film’s premiere.

The Jazz Singer made $3 million, turning Warner Bros. Studios from a fly-by-night operation into a major player. Warner Bros. was able to buy First National in 1928, and the surviving brothers decided to build a theater in Youngstown as a memorial to their brother Sam.

“They left here penniless, and came back laden with gold,” Heffernan said at the Warner Theater opening.

Town Talk magazine, which billed itself as Youngstown’s version of the New Yorker, called the Warners were an American success story fit for the movies themselves—one of many that could be found in Youngstown.

[blocktext align=”right”]“The story of the personal and business successes of Youngstown … reads almost like a fairy tale or a story of adventure served to our youth to entertain them and possibly inspire them to a desire for attainment…”[/blocktext]“The story of the personal and business successes of Youngstown and those who assisted in its development, and those she sent forth to success in many and varied fields throughout the country, reads almost like a fairy tale or a story of adventure served to our youth to entertain them and possibly inspire them to a desire for attainment,” the magazine wrote in an issue commemorating the opening of the theater. “This story is not fiction. It is fact and is the more glamorous being so.”

No expense was spared in constructing the Warner Theater, at a cost of $1.5 million. The materials used in construction were a trip around the world, with Macassor ebony, Carpathian elm, Italian olive wood, Australian cherry and mountain elm, English walnut and oak and African cherry.

The Warner, unlike the other theaters in downtown Youngstown, was built specifically for movies. But it also had a Wurlitzer pipe organ that could be lifted into place in an orchestra pit by a hydraulic elevator. The stage was surrounded by a total of 14 rooms that could be used as dressing rooms for live stage shows. (Ironically, in its existence as the Warner Theater, the great theater hosted no stage shows.)

The lobby of the theater was lined with mirrors, drawing inevitable comparisons to the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. An ornate marble staircase led up to the balcony seating, which was cantilevered so nobody had to sit behind a pole. The projection booth had its own bathroom and shower facilities.

[blocktext align=”left”]It was estimated that enough power was used at the Warner to light up 2,500 homes.[/blocktext]In the walls of the Warner were 6,200 lamp sockets, 63,000 feet of steel pipe and 325,000 feet of copper wire. It was estimated that enough power was used at the Warner to light up 2,500 homes. The overbuilding was by design, as there were plans for a 20-story hotel to be built on top of the theater. At the time, the tallest building in Youngstown was the 18-story Metropolitan Tower, an Art Deco skyscraper opened in 1929 on West Federal on the city’s central square, kittycorner to the Palace. The Metropolitan Tower still stands today.

The Warner capped a building boom in downtown Youngstown. The Stambaugh Building was constructed in 1907, followed two years later by the Mahoning National Bank Building. The Home Savings & Loan Building—with the clock tower that remains the company’s logo—opened in 1919. Two hotels rose in downtown, the Pick-Ohio in 1913, and the Tod Hotel in 1916. McKelvey’s and Strouss’ department stores sold just about everything that the booming middle class could want.

[blocktext align=”right”]The booming city worked hard, but entertainment wasn’t an afterthought.[/blocktext]The booming city worked hard, but entertainment wasn’t an afterthought. The Liberty Theater—decorated with reliefs of Lady Liberty from $20 gold pieces—was built in 1918 for vaudeville and live shows. It was designed by C. Howard Crane, whose name is familiar to students of Detroit architecture. Crane also designed the Detroit Olympia, the Fox, Fillmore, and United Artists theaters, as well as consulting on the design of the Detroit Institute of Art.

In 1926, a black-tie gala marked the opening of the Palace, then called the Keith-Albee Theater, which featured Betty and Burt Wheeler, a singing and dancing act. The theater was equipped to host the top live acts of the day, with a 50-by-32 foot stage that hosted ice skating exhibitions, 12 dressing rooms and an underground passage bringing performers from the Tod Hotel right backstage. In 1933, the theater reopened as the Palace, equipped to handle movies as well as live shows. The Palace would host live performers throughout its history, including Laurel and Hardy, the Andrews Sisters, magician Harry Blackstone, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. In 1928, the State Theater opened on West Federal Street, touting its $50,000 Kimball organ.

But in just a few short years, vaudeville acts gave way to movies as the most popular entertainment of the day. The Liberty was bought by Paramount in 1929 and renamed for the studio that now owned it. The theater underwent a $200,000 renovation—including air conditioning—to enable it to show talking pictures.

[blocktext align=”left”]The Warner was the high-water mark for downtown construction.[/blocktext]But the Warner Theater was the high-water mark for downtown construction. Frontage on West Federal Street was going for $10,000 per square foot. As the Great Depression spread and deepened, construction continued, albeit on a more modest scale. More theaters went up, but farther away from the city center. In 1938, the Foster Theater was built on Glenwood Avenue. Four years after that, the Newport was built at a cost of $125,000 in Boardman on Midlothian Avenue, the border for Youngstown and Boardman. Six years after that, the Belmont Theater was built on Youngstown’s northern border with Liberty Township. By 1940, the climb of Youngstown’s population had stalled, but Mahoning County continued to grow.

The battered interior of the Liberty/Paramount, since demolished. Photo courtesy Ohio Office of Redevelopment.

After World War II, the population of Youngstown was starting to migrate out to the suburbs—and businesses followed them.

In 1950, the Boardman Plaza opened on U.S. Route 224 in Boardman Township, south of the city, the first major construction project of the Edward J. DeBartolo Corporation. The company’s namesake would soon grow wealthy in suburban real-estate development. The plaza featured stores, a movie theater—and ample parking. Four years later, the Eastgate section of the Ohio Turnpike—the first 22 miles west from the Pennsylvania state line—opened. The Youngstown exit for the turnpike, which would soon permit high-speed auto travel from Pennsylvania to Indiana, was at Ohio Route 7, south of the city. Access to the turnpike lured Youngstown drivers south, and development followed. Soon DeBartolo and his fellow builders were erecting shopping, hotels and other amenities for travelers and the growing suburban population.

Youngstown Sheet and Tube even left its perch atop the Stambaugh Building downtown for Boardman, building corporate offices and a research center on a 52-acre tract of land not far from the Turnpike exit. Between 1950 and 1960, the population of Boardman doubled to more than 27,000. In that same time, the population of Youngstown dipped by 1,700 to roughly 166,000.

[blocktext align=”right”]The space where Frank Sinatra, the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers played (separately) has long been a parking lot.[/blocktext]The movie theaters downtown tried to keep up. The State closed in 1957 for a remodel, adding the Todd-AO widescreen and sound system, and reopened with The Ten Commandments. The Palace adopted the Cinerama widescreen system. Movie attendance was going strong, and new theaters were popping up—just not in downtown Youngstown. Single-screen theaters were losing out to the convenient variety of multiplexes. A three-screen movie theater was built in the Wedgewood neighborhood of Austintown in 1966. The Southern Park Mall—another DeBartolo project—opened in Boardman in 1970, and included a multiplex. After World War II, four drive-ins also opened, in suburbs adjacent to each of the four sides of Youngstown. The Palace was the first to go dark. It closed after a showing of First Men in the Moon on November 29, 1964. The theater was losing its film distributor, and the building itself was sold to a developer who had grand plans for an eight-story building with apartments, shops and a movie theater—of course, a multiplex—on the ground floor. The following year, the fixtures were auctioned off. A crowd of around 200 came to see the Palace one last time before it was bulldozed. The grandiose redevelopment plans never occurred, and the space where the Palace once stood—where Frank Sinatra, the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers played (separately)—has been and remains a parking lot.

On February 28, 1968, the Warner Theater played its last movie, Bonnie and Clyde. For the only time in its history, the theater was oversold, and refunds had to be given out to 200 people.

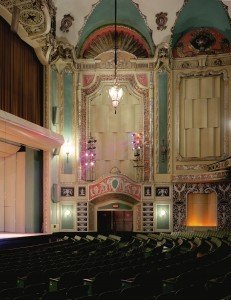

The lobby of the Powers Auditorium, nee Warner Theatre. Photo courtesy of the Mahoning County Convention and Visitors Bureau.

“One man looked at the trappings, the curtains and ornate fixtures, and expressed sadness that the theater was being closed,” manager Marie Wollitz told the Youngstown Vindicator. Wollitz had worked at the theater since a month after it opened. “He admitted he hadn’t been to the theater in years, and I told him that’s one of the reasons it is being closed.”

Declining patronage was a big reason, but it was just one of many. Theater distribution and ownership companies merged, resulting in an overlapping of areas covered by theaters. Vindicator Theater Editor Fred Childress said that in 1950, there were 11 theaters in the Youngstown area—a marked decrease from the 23 that served the area during the Great Depression. By 1970, the number was back up to 20 theaters—but the decline of the studio system meant fewer movies were available for distribution.

The Warner Theater had a date with the wrecking ball. An auction was scheduled for September 21, 1968, and plans were announced to turn the theater into a parking lot. But the loss of the Palace had made Youngstown cautious about protecting its architectural heritage. Edward and Alice Powers donated $250,000 to buy the building and make it the permanent home of the Youngstown Symphony. The Warner had become Grand Central to the Palace’s Penn Station—saved through the lesson of the destruction of its sister.

Powers, a stockbroker, had no affiliation with the symphony. But he remembered the Warner Theater. “It would have been a crime to tear it down,” Powers said. “The heritage of being from here and knowing Federal Street in its heyday, as well as its sad days, led us to consider the gift.”

A detail of the interior of the former Warner Theatre. Photo courtesy of the Mahoning County Convention and Visitors Bureau.

The idea was brilliant in its simplicity: Convert an existing movie theater—many of which were originally built for stage shows—into a live concert and play venue. Converting a theater was far less expensive than building a new facility. In the case of the Warner, the cost worked out to roughly $170 per seat, a fraction of the cost of new symphony centers built elsewhere around the same time. After the idea proved workable in Youngstown, Pittsburgh’s Civic Light Orchestra—which abandoned its new arena in the Hill District because of terrible acoustics—refurbished Loew’s Penn Theater (another Rapp and Rapp creation) as its new home, Heinz Hall. The Civic Arena would soon find a new tenant when the National Hockey League gave Pittsburgh an expansion team.

The renovation was estimated to cost around $750,000, but a lot of time and services were donated by local businesses and unions.

The Warner Theater was renamed Powers Auditorium. It might not have looked great when the restoration started, but it had aged well. The tile floors needed little repair, but the slope toward the theater was leveled off so the lobby could be used for banquets. The original seats and carpeting had to be thrown out, and the draperies virtually disintegrated to the touch, but the building remained structurally sound. Engineers were pleasantly surprised at how good the building’s acoustics were, which they tested by standing onstage and firing a pistol.

The Powers Auditorium at the Deyor Performing Arts Center, formerly the Warner Theatre. Photo by Vince Guerrieri.

[blocktext align=”right”]Engineers tested the Warner’s acoustics by standing onstage and firing a pistol.[/blocktext]In 1969, amid considerable fanfare, albeit not the equal of the Warner Theater opening, Powers Auditorium debuted with a performance of Die Fledermaus by the Youngstown Symphony Orchestra on Sept. 20, 1969. Judge D. Barry Dickson, president of the Youngstown Symphony Society, borrowed a line from Samuel Taylor Coleridge and described the new Symphony Center—the first home owned by the symphony since its 1936 founding—as a stately pleasure dome. Today, Powers Auditorium is the centerpiece of the Deyor Performing Arts Center, named for one of its benefactors, Denise DeBartolo York. Her father was Edward DeBartolo, the developer whose own suburban pleasure domes helped hasten the demise of downtown theaters.

The State became a different kind of music venue. After its closing, it reopened in 1973 as the Tomorrow Club, a live rock ‘n’ roll venue, with a performance by a native of Wichita, Kansas and one-time Kent State student, Joe Walsh. The State operated as the Tomorrow Club until 1978, and then as the Youngstown Agora until 1982. The list of rockers who played the former movie palace includes Huey Lewis & the News, Joan Jett, the Ramones, Chrissie Hynde, Devo and the Talking Heads.

The State closed as a live music venue in 1982, amid complaints from other business owners that the concert audiences were bringing vandalism and other criminal behavior downtown. By then, most downtown business owners were holding on for dear life.

[blocktext align=”left”]September 19, 1977, is still referred to as “Black Monday” in Youngstown.[/blocktext]September 19, 1977, is still referred to as “Black Monday” in Youngstown. That day, Youngstown Sheet and Tube—which had been bought eight years earlier by the Lykes Corporation in New Orleans—announced the closing of the Campbell Works at the end of the week, throwing 5,000 people out of work. That was the beginning of the end. By 1983, Sheet and Tube was gone, and most of the other Mahoning Valley steel mills and factories—facing loss of raw material, increasing labor and transportation costs and pressure from foreign imports—were closing down as well.

The Paramount’s final show as the last first-run theater in Youngstown was Strawberry Statement in 1970, but it reopened two years later as a theater showing kung fu and blaxploitation movies, starting with Cleopatra Jones. The theater was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. The State was also added to the Register in 1986, citing its terra cotta façade.

At right, the terra cotta facade of the State Theatre, all that remains of the former movie palace. Photo by Vince Guerrieri.

A buyer stepped forward for the Paramount with plans to turn it into an entertainment venue in the 1980s, but funds never materialized. At the time, nobody was investing in downtown Youngstown. The two department stores were bought out by chains and ultimately closed down. Restaurants went under or moved to the suburbs. A scheme to turn Federal Street into a pedestrian mall was no help.

Plans came up again in the 1990s to turn the Paramount into a dinner theater, but again, the money wasn’t. By this time, the postwar suburban theaters that had supplanted downtown’s palaces had themselves become outdated. The site where the Newport was built is now a Burger King. The Wedgewood Cinema is now a nightclub. The theater at the Boardman Plaza is now a county courthouse. The Foster Theater still exists on Glenwood Avenue, but it has become a relic in its own way, an adult entertainment venue in the days of the Internet.

[blocktext align=”left”]The revival came too late to save the State or the Paramount.[/blocktext]In the late 2000s, reinvestment came back to downtown Youngstown. Harry Burt’s former confectionary on West Federal is being turned into the Tyler History Center. The Erie Railroad Terminal on Commerce across the street from where the Palace stood was renovated. It’s now home to apartments and shops on the ground floor. No multiplex. A business incubator and a state office building have sprung up on West Federal.

With the redevelopment has come nightlife. Bars and restaurants dot West Federal, and there’s even the Covelli Center, a venue for minor-league hockey, athletics, and concerts on the site of a former steel mill. A renovated movie theater wouldn’t be out of place. But this revival came too late to save the State or Paramount.

Both theaters moldered for a lack of funds or function, with little or no maintenance performed. The city bought the Paramount in 2012 and tore it down the next year. It had outlived the State, which was demolished in 2008. The terra cotta façade that earned a place on the National Registry of Historic Places is all that remains, fronting a hole in the ground awaiting future development. ::

Image of Paramount Theatre c. 1930 via CharmaineZoe, used under a Creative Commons license.

Do you like what we do here at Belt? Consider becoming a member, so we can keep delivering the stories that matter to you. Our supporters get discounts on our books and merch, and access to exclusive deals with our partners. Belt is a locally-owned small business, and relies on the support of people like you. Thanks for reading!

I would like to know the name of all the movie theaters that were present in Downtown Youngstown from the 50s thru the 70′

Thank you!

My grandfather was the mayor Joseph L. Heffernan mentioned in the article. Just joined as a member and am enjoying the Youngstown Anthology.

I found an original Warner theatre 75 cent ticket #110372 that somehow escaped being ripped. Would you like to have it?