By Barbara W. Dueholm

Chicago’s Greyhound bus terminal in late August 1966 certainly lacked cheer and charm, and perhaps safety. But to me, holding a one-way ticket back to Calumet County, Wisconsin, it was a suitable escape platform from my job as a “Summer Girl” and a puzzling family situation—a family that I wasn’t a member of, but had somehow become the center of. When I had arrived in Chicago that June, I had no idea that a family could implode so completely as to leave me, a 15 year old, in charge.

Back in the 1960s, the Sunday Milwaukee Journal carried columns and columns of advertising from Chicago families rich enough to pay a teenager to look after their young children for the summer. Their older children, presumably, were sent away to camp. The Help Wanted: Summer Girl ads were mesmerizing. This family has an in-ground swimming pool; this one belongs to a tennis club. I didn’t play tennis but dreamed of having lots of free time to learn.

Really, how difficult could taking care of two young children be? I was already saddled with six younger brothers and sisters to watch daily, ages 18 months to 13 years. And that was without the diversion of a backyard pool or access to a tennis club. Yes, we had fields of hay, timothy, and clover to tromp through; stands of pine on the hills too steep to farm and other such rural amenities. But a backyard pool, to my 15-year-old mind, would make child care a snap. So my Summer Girl job search became refined to only those families offering a pool and two or fewer children.

About a half-dozen carefully written letters were sent out, explaining how much childcare experience I already possessed and how perfect I was for the position. A critical detail: yours truly already knew how to swim. My still-tender age, not being an asset, was barely mentioned.

Soon enough, a response came from an elegant-sounding woman with two children, ages two and four. A few additional telephone calls with the charming Mrs. Wallace cemented an offer of employment, to begin immediately after Memorial Day. The Wallaces had the requisite backyard pool; I’d have the unthinkable luxury of my own room and one-and-a-half days off per week. The pay was $25 per week, cash, so not only would I return home that fall with a tan but I’d also be rich. If there was any guilt about abandoning my 13-year-old sister to care for the siblings I was leaving behind, it didn’t register at that time or afterward.

My father put me on the train in Fond du Lac on a sunny early June morning. He had always tended toward being a martinet: Speak only if you are asked a question; never contradict an adult, don’t go barefoot indoors or out; be good. In my entire life he’d never said “I love you” to me or anyone in my earshot. That morning as I boarded the train he kissed my forehead and said simply: Be good.

Apart from traveling solo for the first time ever, only one other thing was memorable about that train trip: the delights of Chicago awaited me and my unquiet mind skipped from one imagined fantastic scene to another. This summer would be fun.

Chicago’s train station was and remains impressive, even if you’re not a 15-year-old who’d barely ever left Calumet County, Wisconsin. When I disembarked there was a family, seemingly awaiting an arrival. But they can’t be my summer family. They have three children, one a baby. Mrs. Wallace had said a two- and a four-year old. Nevertheless, they approached and called my name. Yes, that’s me. The gentleman introduced himself: I’m Dr. Brandt. Mrs. Brandt quickly explained that Mrs. Wallace actually had secured another summer girl, and had given me to Dr. and Mrs. Brandt for the summer.

Given me? Three children instead of two, the baby not even a yearling, and no return ticket home. Be good, be good, be good echoed in my underdeveloped little brain. Lacking any other option, I followed the Brandts out of the imposing station into the bright sunlight to their car. Here things started looking up: Dr. Brandt drove a red-and-white ’65 Ford Galaxie convertible. Certainly they must also have a backyard pool. Dr. and Mrs. Brandt took the front seat; the three children and I were in the back. Soon enough I fell into conversation with Kevin, age four and a half, and Susan, age two and a half; poor Baby Brandt at only eight months could only wheeze and stare at me as I held him in my arms for the trip home.

In the roller coaster that is indentured servitude, the next dip was the size of the house itself: a small and narrow two-story townhouse, connected to endless others, with only a tiny backyard … and no pool. The first floor contained a small living room, dining room, and a galley kitchen. Upstairs were three small bedrooms and a bath. Dr. and Mrs. Brandt had the largest bedroom, of course. Kevin and Susan shared a room and Baby Brandt was in the smallest room. Any idea of my own private room evaporated. The house tour finished in the basement where a space had been set up for me, partitioned with bright pink bed sheets hung from the ceiling to hide the mechanicals from me. Back in Calumet County, to my knowledge, not even the poorest of the poor slept in the basement. The basement was for storing potatoes and onions and jars of canned fruits and vegetables; perhaps laundry was done there but never was it a place to sleep. In my mind echoed the direction: be good, be good, be good. So there I was, in my little basement space shrouded in pink linens from the furnace, the washer and dryer, the ironing board, and the hot water heater. Not a basket of potatoes or a bag of onions or a jar of vegetables could be seen, unless I could be called such.

This definitely was not the romance and excitement I’d signed up for, but what could I do but stay overnight. My own home in rural Wisconsin was an overcrowded, noisy, and difficult place but at least there I didn’t have to sleep in the basement. Unless they are sociopaths, most 15-year-olds don’t know how to hide grave disappointment—even without uttering a word. So Dr. and Mrs. Brandt immediately set about shoring up the relationship. I wore glasses, unattractive ones, as they all were back in 1966. Would I like to get contact lenses? What ugly-duckling 15-year-old didn’t? That could be done instantly as Dr. Brandt was completing his residency at a large Chicago hospital. It would be their treat! No deduction from my pay. Only later did I learn those coveted contact lenses, far too expensive for my family to afford at retail, were of no cost to them—they were prepared at a teaching hospital where doctors did favors for one another. Ditto for some deferred dental work I clearly needed. I thawed. Three children, including a baby, and the pink sheets, could, I suppose, be tolerated.

Mrs. Brandt was 27; tall, lean, with long dark hair. Even in early June, she already sported a very nice tan. A sheltered place in the tiny backyard was her permanent and daily tanning space, complete with chaise lounge and side table for iced tea. My own mother loved to sunbathe and she’d worked out a similar, secluded setup back in rural Calumet County, minus the iced tea.

The first two weeks were a whirlwind of eye and dental appointments at Dr. Brandt’s hospital. Mrs. Brandt drove me and the children from suburban Niles “into town” in her snazzy convertible. In a matter of days my ugly eye glasses were history. That all this got done so quickly and without any fuss seemed miraculous at the time. After the wooing promises made on my first day were met, we settled in.

Dr. and Mrs. Brandt received the Chicago Tribune daily. The first order of business for Mrs. Brandt, still dressed in a beautiful negligee, was to carefully peruse the entire paper for the large clothing ads placed by Marshall Field’s which she did at the dining room table, while drinking coffee and smoking Kent cigarettes. When that was done, she would phone Field’s and ask them to send over items she fancied—sometimes one or two but more frequently a half dozen or more. Everything arrived promptly and she set about trying on each item. I could not figure out why the delivery guy didn’t just wait, because 80 percent of it got sent back that same day: wrong shade of green; didn’t like the drape of the skirt, didn’t flatter her figure. Had she never exited the dress-up doll stage, I wondered. But she kept enough items to annoy Dr. Brandt regarding her spending.

Mrs. Brandt had a seemingly wide range of lady friends that she frequently spoke with on the telephone. The long cord from the wall-mounted phone in the kitchen easily stretched to the dining room table, so neither smoking nor drinking coffee had to be compromised during her chats. Often she would arrange a lunch date with one or more friends, which meant dressing up in one of those fabulous outfits from Field’s and going out. None of her friends ever came to the house. Mrs. Wallace, who had “given me” to Dr. and Mrs. Brandt, called early on to lament that her Summer Girl, the very one she’d thrown me over to get, had left her after only a few weeks. Would Mrs. Brandt give me back to her? Mrs. Brandt laughed when she related that conversation. Instead of feeling any regret, my only thought was how horrible that household must have been for a Summer Girl to give up a backyard pool and a private room to return early to Wisconsin.

The days fell into a rhythm: Get the children up in the morning, feed them, and make certain they were entertained afterward; do laundry when necessary. Make a serviceable lunch for the children, and then get them down for a nap, after which we’d walk to the park to get some space and air. Baths after dinner at night and then off to bed for the children and for me.

Now that she had a Summer Girl to manage the household, Mrs. Brandt could also nap daily. Perhaps because of all the coffee consumed, she herself had a difficult time getting down for a nap. So she asked me to give her a back massage prior to her daily nap. She was nonchalant about the request, so it never occurred to me to decline. Our neighbor back home, Mrs. Haberman, paid me 50 cents a week to wash her hair and put it up in pin curls. Mrs. Brandt’s request for a back massage didn’t strike me as materially different from fiddling with Mrs. Haberman’s hair. During that quiet hour or so each afternoon when everyone else napped, I explored. They had a nice hi-fi, tons of record albums—Jack Jones, Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, and Tony Bennett. My life-long fondness for standards, accompanied by lush strings, can be dated from that period. They also had a very modest library: Jane Austen, Herman Melville, George Eliot. More interesting to me were the many large photo albums full of romantic pictures of Dr. and Mrs. Brandt enjoying foreign scenes. In the photos they always looked so sophisticated and so happy; I never tired of looking at them.

Dr. Brandt was also tall and dark-haired but as burly as Mrs. Brandt was lean. He was 30 and had been notified that as soon as his medical residency was complete in the fall, he would be drafted and sent to an Army post in Texas. To Mrs. Brandt, her husband’s impending military service was unfair and cruel. Texas was worse than the USSR, for God’s sake. Where would she wear her fur coat? That Dr. Brandt didn’t cause the Vietnam War, or the draft, was not consequential to her.

My one evening and day off per week were cherished solitary hours. Although I was only 15, the local multiplex admitted me to Irma la Douce, Thunderball and lots of other age-inappropriate fare. The newly-acquired contact lenses and careful use of eye makeup worked their magic. Sunday was reserved for church. I’d never been big on it, but services gave me a reason to get out of the house for hours. Our Lady of Ransom was not only a suitably long walk away, but also suitably named for my experience. My fit of weekly religiosity caused Dr. and Mrs. Brandt to mirror it in their own religious rituals at home. Both my religiosity and theirs were short-lived.

In that tiny house with only the ground floor as common area, Dr. and Mrs. Brandt’s arguments were impossible to miss: below the children’s bedrooms and above mine, they battled on the first floor. Money and spending, the draft, and the woman next door were recurring topics. Doris lived in the townhouse next door; she was the human embodiment of a Barbie doll—at least from the waist up. In 1966 vernacular, Doris was stacked … and blond … and tan. She and her architect husband (no kids, I was thankful) were frequent backyard guests at Dr. and Mrs. Brandt’s for pre-dinner cocktails, smoking, of course, and chatting. What heterosexual guy would not look at Doris, in her halter top and shorts and perfect tan? But to Mrs. Brandt, looking was the prelude to all sorts of out-of-bounds activities. That Dr. Brandt worked so much as to make dinner at home a rare treat did not register with Mrs. Brandt. So the arguments and accusations escalated: She would not move to Texas; he would not support her spending; she would not countenance his seeing Doris; he insisted Doris was only a neighbor. This was not unlike the verbal jousting I’d experienced at home; only the topics at issue differed.

[blocktext align=”right”]But after my contact lenses were in place, my dental work taken care of, and my credibility as a reliable Summer Girl firmly established, all hell broke loose.[/blocktext]

But after my contact lenses were in place, my dental work taken care of, and my credibility as a reliable Summer Girl firmly established, all hell broke loose.

I got up one early July day to find Mrs. Brandt, as usual, having coffee and smoking Kent cigarettes at the dining room table with the Tribune spread out in front of her. Also as usual, Dr. Brandt had spent the night at the hospital on call. Medical residencies are tortuous.

Mrs. Brandt calmly told me she was leaving to visit her parents in California; that a taxi would be there momentarily. She had left cash and groceries for me; milk would continue to be delivered. Dr. Brandt would provide more money as I needed it. The children were getting up so I fed them breakfast. But when are you coming back, I asked? Is Dr. Brandt coming back? It didn’t immediately dawn on me that she had no plan to come back. With all my other questions unanswered, I blurted out: But what about Baby Brandt—he has asthma. What should I do? Oh, just walk him in the night air, said Mrs. Brandt.

The taxi came and with sweaty effort the driver hoisted multiple heavy pieces of luggage into the trunk. Mrs. Brandt was gone. The children seemed nonplussed. Had this happened before? How could it have with Baby Brandt only 9 months old? An immediate call to my parents provided no help at all. “Don’t leave those babies” was really all that my mother said. Wait, I’m just a baby myself! Be good, she said; be good.

Left alone with three children under age five, a full larder, stacks of record albums, and more cartons of Kent cigarettes in the cupboard than I’d ever seen in private hands, I did what any other abandoned 15-year-old might. I made chocolate chip cookies by day, and after the children were in bed each night, learned to smoke Kent cigarettes and appreciate the standards sung by the greats. When Baby Brandt had his usual asthma attacks, we walked in the night air. Kevin and Susan did not like this one bit, parading down the sidewalk in their pajamas, but I could not leave them alone at home. We’d walk, walk, walk. I continued to sleep in the basement even with an empty bedroom upstairs. I’d been in it only immediately after Mrs. Brandt left, just to see if she’d left any clothing behind. She hadn’t. Dr. Brandt called periodically; did I need money? When I did, he brought it, staying only briefly to nuzzle the children, whom he clearly adored. It stung that he would not stay more than a few minutes, but what man would, with a 15-year-old girl in the house and already accused of stepping out with a neighbor?

I pleaded with my family by letter and phone: please, please can I leave? Always the same answer: Don’t leave those babies. Be good, just be good.

It took little time for the generous larder to run low. The grocery store was blocks away; I could not possibly carry the shopping back in the pram with Baby Brandt. Temptingly, that snazzy convertible was right there. Mrs. Brandt had given me the keys when she left for California. No matter that I wasn’t old enough yet for a driver’s license. I’d driven a tractor—standing up so I could shift gears—and I’d driven my older brother’s 1950 Hudson stock car around a hay field. Surely I could get the hang of the Galaxie’s automatic transmission. Off we went, convertible top down whenever possible, to the grocery, to a park too distant to walk. What was the harm? Even with a driver’s license, no one wore seat belts or used car seats in those days. Four-and–a-half year old Kevin was deputized to hold Baby Brandt.

It took little time for the generous larder to run low. The grocery store was blocks away; I could not possibly carry the shopping back in the pram with Baby Brandt. Temptingly, that snazzy convertible was right there. Mrs. Brandt had given me the keys when she left for California. No matter that I wasn’t old enough yet for a driver’s license. I’d driven a tractor—standing up so I could shift gears—and I’d driven my older brother’s 1950 Hudson stock car around a hay field. Surely I could get the hang of the Galaxie’s automatic transmission. Off we went, convertible top down whenever possible, to the grocery, to a park too distant to walk. What was the harm? Even with a driver’s license, no one wore seat belts or used car seats in those days. Four-and–a-half year old Kevin was deputized to hold Baby Brandt.

My parents visited. They only stayed an hour or so, just to make certain, I think, that the children in my care were OK. They brought several pounds of Sheboygan bratwurst in the wholly mistaken belief that familiar food might keep me from getting too homesick. Neither Kevin nor Susan had ever heard of, much less tasted, bratwurst. But as I was the cook, that’s what they got—until it ran out. If nothing else, it was a break from the constant stream of casseroles, one of the few things I felt confident making. No one, not neighbors nor my parents, ever advised me to contact Child Protective Services. I did not know there was such a thing as Child Protective Services.

The back lot neighbor, Mrs. Theobald, was a retired tailor and she befriended me. Not enough to offer to watch the children for a few hours so I could get a break but I enjoyed our chats. Unable to fit all the new acquisitions into her closets, Mrs. Brandt had given me several of her clothing cast-offs. Mrs. Theobald offered to tailor them to my barely 5’3” height. So we spent the children’s nap time together many days, me modeling the clothing and Mrs. Theobald on her knees with a pin cushion strapped to her wrist and her lit cigarette in an ashtray nearby. My very favorite was a form-fitting jewel-toned sleeveless dress with a little bolero jacket; no way did I look 15 in thatoutfit. Mrs. Theobald always referred to Dr. and Mrs. Brandt as “Blair” and “Carol” which I could never bring myself to do; she also had lots of free time to observe the neighbors. She told me that the marriage between Doris and her husband was doomed. I was aware of “doomed” marriages back home—too many babies, too much alcohol, total incompatibility. But Doris and her husband intrigued me—what could be wrong with their union? How could that be, I asked Mrs. Theobald. Oh, he doesn’t really like girls, she said. That was an entirely new reason for me to think through. Her forecast about Dr. and Mrs. Brandt’s marriage was similarly pessimistic—but for different reasons. Well, Carol comes from wealth, she said and Blair does not; doesn’t matter that he’s a doctor. The draft into the Army only hurried down the inevitable, she concluded.

The daily routine went on and on: children fed, entertained, bathed and put to bed; clothing laundered, groceries purchased. Not one phone call came from Mrs. Brandt. By mid-August I finally told Dr. Brandt that I’d have to return home soon. My junior year in high school would begin after Labor Day. Who knows what phone lines lit up across the country, but in less than a week, Mrs. Brandt and her parents materialized. Mrs. Theobald told me Mrs. Brandt’s family had made their fortune out east in the girdle business, women’s girdles being very big business in the ‘40s and ‘50s. In retirement they enjoyed the endless summer that is Southern California. Mrs. Brandt’s mother wore lots of large and expensive pieces of jewelry. She was a tiny blond woman and all that jewelry made her look even smaller. Mrs. Brandt’s father, like her, was tall and lean. Awkward introductions and pleasantries were exchanged. The weeks-long abandonment of children and family was not mentioned. In fact Mrs. Brandt said almost nothing at all, leaving her parents to do the heavy conversational lifting. Her father pulled a roll of bills from his pocket and paid me. Now I could leave.

Kevin, Susan and Baby Brandt said good-bye to me with as much emotion as they’d shown their own mother when she’d left them weeks before. The taxi took me, my newly tailored clothing, and my smuggled packs of Kent cigarettes to the bus station. I didn’t know enough to tip the driver. Settling into my seat, the euphoria of being allowed to return to my own dysfunctional home ebbed. I thought about my summer and concluded that, except for the smoking part, I’d been good enough.

Kevin, Susan and Baby Brandt said good-bye to me with as much emotion as they’d shown their own mother when she’d left them weeks before. The taxi took me, my newly tailored clothing, and my smuggled packs of Kent cigarettes to the bus station. I didn’t know enough to tip the driver. Settling into my seat, the euphoria of being allowed to return to my own dysfunctional home ebbed. I thought about my summer and concluded that, except for the smoking part, I’d been good enough.

Barbara Dueholm is retired from the public broadcasting division of the University of Wisconsin Extension.

Do you like what we do here at Belt? Consider becoming a member, so we can keep delivering the stories that matter to you. Our supporters get discounts on our books and merch, and access to exclusive deals with our partners. Belt is a locally-owned small business, and relies on the support of people like you. Thanks for reading!

This was great. I loved the way she effortlessly takes is back to a very different time.

Yes, a very different time, when smoking cigarettes was considered cool and wearing seat belts was not. BWD

I love this story! I almost cheered aloud when the bratwurst showed up.

I love the vibrancy of the author’s writing, especially describing driving Mrs. Brandt’s car to get groceries. Nice.

Bravo! Terrific story and beautifully written. Too bad Mad Men has finished shooting, “Summer Girl” would have been a great episode.

Great story! I’ve been sharing it with friends.

Moderation? This is a wonderfully well-told and well-worded story. Anyone who has cared for kids or convertibles or the ’60s or bratwurst or just enjoys reading about people has a treat in store.

Oh, I absolutely LOVED this piece! I went through so many emotions reading it…concern for that 15-year-old girl, laughter/horror that “all hell broke loose,” shock that anyone could abandon children like that…and, as Charlotte mentions above, the idea that bratwurst could cure homesickness.

I’m also impressed with the pluck of this girl! Resourceful indeed! A great read, and I plan to tell my friends.

Such a great piece! Proof that reality often provides much more solid, interesting material than anyone’s imagination could ever construct.

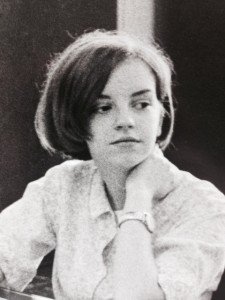

Having known the author, having come from Wisconsin, and having lived in Chicago while regularly driving up to Niles, the most vivid anchor in all of this is somehow the idea of an Emma Watson look-alike listening to standards and smoking Kent cigarettes while a good part of the would-be cast of Peter Pan slept upstairs. This is a beautifully told and bizarrely gripping story.