By Daniel J. McGraw

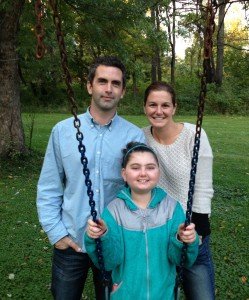

Like most ten-year-olds, Erin Potter has to be tracked down on a sunny and bright Sunday afternoon. Used to be moms would yell their kids’ names out the front door or tell some of the neighborhood kids poking around to tell Erin she needs to come home, but that’s not how things work these days. So Jeni Potter texts her daughter that she should come home to talk to that reporter who wants to ask her some questions.

Erin comes in the kitchen door a few minutes later, having had to give up some ice cream cake-eating with the kids down the street. She crawls up with her mom on the couch, not seemingly bothered by losing out on cake and play, but not exactly showing any great thrill to be sitting in a room with some stranger with a legal pad and a pen either.

She is, after all, ten, a fifth-grader living in suburban Kirtland, Ohio, who is on that great precipice of life where the world starts to make sense and you begin to let everyone know you know about stuff. And you can see that instantly in this kid’s eyes, they sparkle and move quickly above a mischievous smile, playing that game where she lets you know she’s used to this attention though she doesn’t like it all the time. That’s why some of her answers are of the “I don’t know” variety, delivered with a playful twinkle in her eyes.

Erin gets a lot of attention because she has had leukemia for seven of her ten years on this planet, and in 2011 spent 200 days in the hospital getting radiation and chemotherapy and enduring all sorts of pills and poking and prodding from cancer specialists. She has had two bone marrow transplants – one using the blood from her baby sister’s umbilical cord – and her face is a bit puffy these days from the steroids she needs to take to get her immune system to accept the new blood cells from the second transplant about a year ago.Twice a week she goes to Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital in Cleveland to have her blood “cleaned,” for lack of a better word. She has semipermanent small intravenous tubes in her chest, and the blood is pulled out and passed through ultraviolet light and then returned to her body (“extracorporeal photopheresis” or ECP), with some hope that the white blood cells and T-cells and immune system might get back to a better balance.

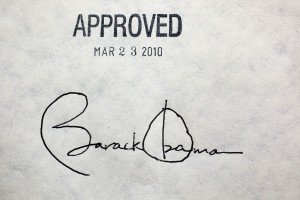

But Erin Potter is more than just a kid with cancer. She is an example of what was wrong with the old health care system and maybe what is better under the Affordable Care Act. Her parents had health insurance from Jeni’s job as a public school teacher, and her husband, Kevin, a marketing/sales consultant, had paid their premiums on time. But the insurance policy for the family of five had individual caps: $1 million lifetime for each family member and by the end of 2010 they were getting close to hitting it with Erin.

But in the fall of 2010, the first phases of the Affordable Care Act became law and their insurance carrier did away with the caps the Potters’ had in their policy. Some of this is hypothetical now, but it is very likely that if the ACA had not been passed, the Potters would have had to either become poor by not working in order to qualify for charity care, accept care and declare bankruptcy when they could not pay, or maybe even get turned away for treatment. No one knows what might have happened, but anyone with a sense of pragmatism know the choices would not have been good ones.

[blocktext align=”right”]“We were fighting for the life of our child, period.”[/blocktext]“We were fighting for the life of our child, period,” Jeni Potter says. “When things are dark and horrible for a family like we have gone through, [the Affordable Care Act] took one huge thing off the table. We didn’t have to worry about losing insurance or getting charity or government coverage. We didn’t have to worry about changing our jobs or losing our house.”

And for Kevin Potter, his family’s example is one that people should be focusing on as the next round of ACA enrollment starts next month. “I’ve heard all people claim this is another government handout,” he says, “but there were more and more people like us who were going to get screwed by the health care system. What was happening is people wanted to buy insurance and pay their share, but the system was finding ways that they couldn’t get covered or why treatment might be denied.

“In our case, we were paying our fair share and still looking at having coverage taken away.”

President Obama told Erin she looked like Audrey Hepburn. Now this poster of the actress hangs in Erin’s room.

President Barack Obama took note of the Potters’ situation as well. He met them during a 2012 campaign stop in Mentor, Ohio, and talked to the family backstage before a crucial stump speech three days before the election. “He told me I looked like Audrey Hepburn,” Erin Potter says. When asked if she knew who that was, she laughs and said she did not. But her grandmother bought her a Hepburn poster, and Erin Potter studied up about the actress, and now dreams of going to Paris someday.

“She said ‘Paris is always a good idea,’” the ten-year-old says with serious look. “I dream of going there. It would be sooo awesome.”

***

After his victory over Mitt Romney on Nov. 6, 2012, Barack Obama made one mention of what he knew at the time would be the legacy of his presidency. He didn’t mention the huge validation of Obamacare from the United States Supreme Court six weeks earlier, he didn’t praise staff members who helped pass health care reform, and he didn’t talk about the work still needed to keep the law from being repealed in Congress. From the stage in Chicago, he mentioned a girl he met a few days earlier in Mentor, Ohio:

“And I saw just the other day, in Mentor, Ohio, where a father told the story of his 8-year-old daughter, whose long battle with leukemia nearly cost their family everything had it not been for health care reform passing just a few months before the insurance company was about to stop paying for her care.

“I had an opportunity to not just talk to the father, but meet this incredible daughter of his. And when he spoke to the crowd listening to that father’s story, every parent in that room had tears in their eyes, because we knew that little girl could be our own. And I know that every American wants her future to be just as bright. That’s who we are. That’s the country I’m so proud to lead as your president.”

How Obama came to meet Erin Potter is a weird story in and of itself. Kevin Potter, now 37 and a semiactive volunteer for Democratic candidates for many years, went to the local Obama campaign office in Lake County about two months before the election and said he would be available to knock on some doors. The local campaign staff asked him why he wanted to do that, and he told the story of his daughter and her cancer and how the ACA had made their family life at least bearable because of the lifting of the insurance cap restrictions.

So he went about his door-to-door campaigning for the incumbent president. About ten days before the election he was told that a rally might be held in Lake County – probably Bill or Hillary or Biden appearing – and the staff wondered if Kevin might tell his story to the crowd at Mentor High School. But then a few days later he got a call from the campaign staff in Chicago. They told him the President would be speaking at the event, and they asked if Potter would introduce Obama. “I was pretty shocked,” he says, but he accepted and three days later he was introducing the President of the United States.

The Potters and their three girls – middle daughter Erin plus Annie, 14, and Mary, 3 – all got to meet the President (all Erin will say is “he was real nice”) backstage and then Kevin Potter was ready for his turn in the spotlight. “The girls got shuffled to their seats, and I’m backstage behind this big curtain, and I know my moment is coming up,” he said. “Then I get this tap on my back, and I hear in my ear, ‘You got this, Kevin,’ and I turn around and it’s Obama and he puts his hand on my shoulder and says it again.”Three nights later Kevin and Erin were watching the election results and they waited for the victory speech. Erin fell asleep and Kevin was about to as well, when he heard the mention of the 8-year-old girl from Mentor and just about lost it. “My stomach was doing somersaults and my phone was buzzing and texts were popping up from everywhere,” he said. “I tried to wake up Erin, but she was fast asleep.”

She thinks she watched the speech the following morning on MSNBC’s Morning Joe (she and her older sister Annie watch that before school on many mornings). “It was pretty weird,” she says of the president mentioning her, and “my sister and my Dad told me how big it was.” And that mention in his victory speech has had an effect on the young girl, her mom says.

“Annie is very political and she and Erin talk a lot about what’s happening in Washington, especially about health care,” Jeni Potter says. “It makes Erin nervous when she hears about repealing the law or how she might not be covered any more. But I understand what she is feeling. It makes me nervous too.”

***

Many in this country think Obamacare is horseshit. But when I hear that these days, I tell those same people that if it is horseshit, then you better deal with it, ‘cause you can’t put the shit back in the horse.

The major problem the Obama administration had was in how they explained the ACA. First, they made it much more complicated in trying to sell it to the public than it needed to be, and second, they avoided the obvious point that the ACA is indeed the first bridge to a government-run, single-payer health care system.

[blocktext align=”left”] In effect, the insurance companies were cherry-picking the most profitable clients and leaving the rest to fend for themselves in emergency room care. [/blocktext] Let’s take the first one first. With the aging of the nation’s population, and the baby boomers moving to Medicare, the country’s health insurance companies were seeing the prospect of huge numbers coming off their rolls and high-profit growth rates getting scaled back. That’s why pre-existing conditions started getting excluded from coverage and caps like those the Potters were facing became the norm. In effect, the insurance companies were cherry-picking the most profitable clients and leaving the rest to fend for themselves in emergency room care. It was a way to get the higher profit growth percentages they had gotten in prior decades.

The Obama administration and other presidents prior figured the biggest problem in moving toward universal coverage was getting rid of the pre-existing condition restrictions. Most of the public knew people who had fallen into that gap, and most thought such restrictions were blatantly unfair (poll numbers have always put Americans favoring changes for pre-existing condition restrictions in the 70-80 percent range). The insurance companies said they could get rid of the pre-existing condition clauses, but only if everyone signed up (they didn’t want people signing up only when they got sick and then dropping coverage when they were well). The government said they could only get everyone to sign up if there were some subsidies for the poor.

That was it. We could get universal coverage if we got rid of pre-existing conditions, insurance companies could do that if everyone signed up, and everyone would be able to sign up if we gave some a subsidy to help pay for it. Theoretically, the savings would come from the uninsured not using more expensive emergency room care over the less expensive preventative care that came with their Obamacare, and paying some into a system they couldn’t afford before.And those basic points are made easier to understand if you don’t avoid the second point, which is that the United States is moving closer to a single-paying system every year even without the ACA. The population in this country is now about 315 million, and about 50 million are on Medicare and about 60 million are on Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). So right now, roughly one-third have their health care covered by government programs.

By 2050, projections are that the U.S. population will grow to about 400 million. Of that number, the Congressional Budget Office predicts that about 92 million will be on Medicare and another 100 million on Medicaid. The Medicaid number might be lower because of the ACA, but it is a fairly sure thing that about half of the U.S population in 2050 will be on some government-sponsored health care. And that does not include those who will be getting public subsidies if the ACA private insurance exchanges are still operating.

By 2050, one-fifth of the total U.S. population will be 65 or older, up from 12 percent in 2000 and 8 percent in 1950. The number of people age 85 or older will grow the fastest over the next few decades, constituting 4 percent of the population by 2050, or 10 times its share in 1950. And with age come higher health care costs, and study after study tracks them in trillions of dollars. But the better way to track the spending is what percentage of our economy will be in health care by 2050.

[blocktext align=”right”]…by 2050, about one-third of our gross domestic product will be health care spending.[/blocktext]Many studies, including one by the Congressional Budget Office, say that by 2050, about one-third of our gross domestic product will be health care spending, with about 18 percent of that coming from government spending. To put those numbers in perspective, health care spending was 5 percent of GDP in 1960, and 17 percent in 2012.

That’s why I had problems with the Obama administration not being more aggressive in attacking the “everything is fine and we don’t need to do anything” mantra that many ACA opponents were parroting. Because, though I am not any economist or health care expert, the future health care numbers are so stark that some big change was/is needed. We are inevitably moving to a single-payer system based on demographic changes, so it would make sense to begin the transition now so we’re able to handle things better once we get there.

As an added plus, and one the far right should have embraced, is that the time when private companies are responsible for their employees’ health insurance payments is no longer realistic for either the employer or the employee. Free market advocates have long questioned why American workers often faced the prospect of losing their health insurance if they changed jobs.

And if it wasn’t the fact that our population was getting older and more were unable to get coverage, the impact technology might have in private health insurance industry is now coming to a head. Scientists are now able to isolate genes that indicate a person will have a higher likelihood of a disease like breast cancer, for instance. They are able to do that within days after fertilization. In some respects, we could be coming to a point where a pre-existing condition might be identified nine months before we are born.

In the interest of full disclosure, I signed up for ACA coverage about a year ago. I had worked as a writer for many publications through the years, and had the company health insurance plans for those I worked for full-time. In the early 2000s, I went out on my own and paid for my own insurance for several years. But my income went down, and my health was good, and the insurance rates were rising by double-digits every year, so I paid as I went.

But when I hit 50 about five years ago, and health care became something I worried about more, I checked into buying insurance again. It was mind-boggling. Even in state-sponsored, high-risk pools (which supposedly covered pre-existing conditions), premiums were in the range of $600 a month and they covered nothing and had very high deductibles. I often explained to people that it would be like being asked to pay triple the going rate for car insurance, and then being told you’re only covered in one out of ten accidents. And on the tenth one, maybe.

So I now have coverage, get a small government subsidy (which should be gone next year as my income has gone up), and pay about $2,400 a year. When I tell my friends who hate Obamacare this, they say it’s nice I’m paying now, but they are still subsidizing me. Then I tell them they would be subsidizing me more if I had no insurance and played the emergency room doctor game like most of the uninsured do. They then change the subject by joking that I should have done my part for the health care crisis by dying years ago. Thinning the health-care herd, so to speak.

But then I bring up Erin Potter. Should we have just left her out to die when she hit the $1 million cap? Deny her another $250,000 bone marrow transplant because we had decided as a society only one to a customer? Or maybe substitute prayer for medical care?

No one has an answer for that. They admit that the system is broken and needs to be fixed. Take care of that leukemia girl, they say. Then I ask who else. Not you, they joke. Not me and about 13 million other people who have already signed up, I guess.

***

The old adage “all politics is local” is beginning to show itself in the implementation of the ACA, and nowhere is that playing out as much as in Ohio. What was once an abstract theory and program coming from Washington is now a program that people have and use. About 8 million have signed up nationally for insurance through the marketplace exchanges, and another 5 million through Medicaid expansion. That’s 13 million who are now covered who weren’t before.

In Ohio, about 155,000 have signed up for health insurance under the marketplace exchanges, and another 365,000 have signed up under the expanded parameters for Medicaid that the state signed up for as a part of the health care reform. The Ohio state legislature has to re-up the mostly federally funded Medicaid expansion in June, but it seems more difficult to do that now that. How do you take health insurance away from about 500,000 in Ohio if you halt the Medicaid expansion and repeal Obamacare?

Taking away that coverage might play well in the Republican Party when they are talking national policy, but the congressional leadership is finding that doesn’t play well at home. That’s why Obamacare has faded as an issue from the midterm House and Senate races to be decided next week. The disaster that Republicans predicted did not happen, and most voters know someone who has decent coverage now who couldn’t get it prior to the ACA. In other words, you can’t put the shit back in the horse.

And what is happening is that the big players are now working more to keep the ACA and the Medicaid changes that go along with it. Major hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic and others were largely silent last year when the first enrollment period started, playing a wait and see approach. But Clinic spokesperson Eileen Sheil said the hospital is now considering an ad campaign that will encourage enrollment and to make sure the Cleveland Clinic is part of their new plan. But more importantly, Sheil said, “We are actively lobbying in support of maintaining Medicaid coverage as expanded by the governor.”

MetroHealth, the largest public safety-net hospital system in the state, is also going to work hard on keeping the Medicaid expansion. John Corlett, MetroHealth’s vice president of government relations and community affairs and a former director of the state Medicaid program, said the system is beginning to see savings as it guides patients to being less dependent on the emergency room as their primary care to seeing a primary care physician in the office as part of a preventative care model.

[blocktext align=”left”]“It is a fact that emergency room care is more costly and less effective for the patient in terms of quality care.”[/blocktext]“We were seeing double-digit growth in the emergency room visits in recent years, but it has been fairly steady during the past year without any increases,” Corlett said. “It is a fact that emergency room care is more costly and less effective for the patient in terms of quality care.”

In fact, many hospitals and health care policy wonks nationally are pointing to the success MetroHealth has had with its new enrollees under the state’s Medicaid expansion. MetroHealth got an earlier start than the rest of the state on the expansion due to an experimental waiver program that expanded eligibility in Cuyahoga County. Under that waiver, Corlett said MetroHealth spent $50 million under the cap that Medicaid had set for the system. He also said the hospital found that patients’ health improved more because they were getting preventative care instead of emergency room response.

[blocktext align=”right”]…the longer the ACA and Medicaid expansion is in effect, the more difficult it will be to repeal or make serious changes.[/blocktext]All this means that the longer the ACA and Medicaid expansion is in effect, the more difficult it will be to repeal or make serious changes. More people signed up last year than expected, a large percentage met their payments under the ACA, 28 percent were in the crucial 25-34 demo, and the world did not end as many Republicans had predicted. That’s why Republicans are laying off their Obamacare criticisms in the midterm congressional elections that will be held next week, and that is why the national opposition may have to take a different tack even if Republicans take over the senate as some predict.

Ohio Gov. John Kasich finds himself in that precarious spot of trying to balance the local and national interests on the health care issue. He was one of the few Republican governors who pushed through the Medicaid expansion, and caught some grief from conservatives for doing so. But he defended his expansion of federal health care in Ohio by bringing morality into the debate.

“Now, when you die and get to the, get to the, uh, to the meeting with St. Peter, he’s probably not gonna ask you much about what you did about keeping government small, but he’s going to ask you what you did for the poor,” Kasich said in June of 2013. “Better have a good answer.”

In an Associated Press story last week, Kasich again reiterated that the expansion of health care options for the poor was extremely important in Ohio. “They’re not going to repeal it,” he told the AP. “I mean, you know, that’s not going to happen. It’s really important. I think that opposition to it was really either political or ideological, and I don’t think that holds water against real flesh and blood and real improvements in people’s lives. You know, I talk about it everywhere.”

But the problem for Kasich in this quote is that he is considered one of the likely candidates for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination. His staff immediately said the quote was taken out of context – as athletes often do when they say something they want to take back. His staff said he was only talking about Medicaid expansion and not Obamacare, but the AP produced tapes that backed up their quote and its context to be about the Affordable Care Act.

All of which goes back to the local vs. national debate on health care reform. Local “real flesh and blood” will win out against national “political or ideological” arguments every time. And that’s probably why Obamacare is here to stay in some form or fashion. Because politicians can toe the party line for only so long before they have to go back to their district and get the votes they need to stay in office. And increasingly, more of those voters will have some part of their health care coverage rooted in government programs, and you can’t win elections by taking those programs away.

***

As we talk by the swing set in the backyard, Erin Potter tells me a bit about the latest setback in her cancer treatment. She is dealing with “graft versus host,” which means that the bone marrow transplant has taken over her immune system and the old one is fighting the new one. It has caused some joint pain and muscle stiffness and what were once simple tasks have become difficult.

For example, if she is sitting on the floor, she needs help getting to her feet either from her parents or her sister, or by kneeling in front of a footstool and using her arms for leverage. She had to relearn how to ride a bike because of the muscle memory loss. And she had trouble plugging in the cord that would recharge her cell phone, though she does better with that now (thank God).

She wants to get back into her dancing for her school’s program, because it makes her think of movies and Audrey Hepburn and Paris. Her parents tell me she was recognized by her school for sitting with a new student at lunch who had been alone every day and felt bad for him, but dismisses that and thinks talking about it is kind of stupid.The hospital is never a fun place to be, she tells me, “but the people there are real nice and they’d help me with my homework from the stuff my teachers’ would send to me.” Jeni Potter says that even when Erin was going through many rounds of exhaustive chemotherapy, the hospital staff would have a hard time keeping her in her room because she wanted to hang out by the nurses station to ask questions about their work.

She loves her big family – 23 cousins on her father’s side alone – and she had lots of fun last week helping her big sister Annie get ready for the Kirtland High School homecoming dance. While we are talking, her little sister Mary comes over and Erin helps her get up on the swing like any big sister would. Mary is giggling and laughing and wants to go higher. Erin obliges.

And while you look at her playing with her little sister, you just wish the people who have damned all health care reform as inherently anti-American and socialist and any other horrid buzzword they are using that week could be in this backyard on this bright day. To see an example that health care reform is not just another handout program. It’s “flesh and blood,” as the Ohio governor says, and that part of the debate will never go away.

Daniel J. McGraw is Senior Writer at Belt.

Cover photo by Silvia Jeras (http://www.wishphotocompany.com/)

Support paywall free, independent rust belt journalism — and become part of a growing community — by becoming a member of Belt.

Very nice story and I’m happy that the young lady is getting her treatment.

It’s difficult to discuss this issue in the macro sense. Is health care a right as some argue? Or is it just a large sub-set of our economy? If you discuss the economics, the question quickly becomes…Affordable for who? For my wife and I, Obamacare has had the effect, at least in the short and medium term, of raising our health costs significantly. And that’s if we stay in our current plan. If we going into the exchanges, the increase is dramatic. We’ve checked out the exchanges when a health care nut relative encouraged us to try it out…it didn’t turn out very well.

I understand the Emergency Room argument, but, if true, at some point my health insurance costs should go down as the economies of more coverage empties out the ER’s. I guess I’m skeptical that savings will head in our direction.

On another matter, I’ve always felt it’s a drag on our economy that we connect health insurance with employment. Employment mobility is important to the economy and health insurance/job connections certainly gum up the works.

This is a good story because it puts a face to the working people who need the ACA or expanded Medicaid. While the ACA still needs to be refined it has done some great things for people. This story about the Potter’s is a case in point. We cannot let insurance companies keep someone with a preexisting condition from getting insurance . As the author points out preexisting conditions can be spotted sooner all the time. We cannot turn our backs on people because they were unfortunate and got a disease or got sick. Putting a lifetime cap on a persons insurance is akin to putting a cap on their life. The critics must ask themselves one question. What would you do if it was your daughter?