By Richard O Jones

Although the morning paper said it would be a fair, warming day, the horizon darkened with looming rain. Principal Thomas L. Simmerman watched the fidgeting children lined up in the hall and decided to give them a few minutes of frolic and exercise. A little rain would not hurt them. It was a Friday, and they were always restless on Friday. At precisely 10:15 a.m., September 23, 1904, Simmerman rang the bell, one ominous clang, to release the students of the Pleasant Ridge School for morning recess and watched them file outside.

Support independent, context-driven regional writing.

The school’s enrollment was up by nearly half this year, some 297 children altogether. Around 50 of those came from the nearby village of Rossmoyne, whose school had been condemned by the state. In defiance of an unpopular board of education, the village had three times failed to pass a bond issue to construct a new one, so its students had been reassigned to Pleasant Ridge.

Caring little about the threatening skies, the boys immediately started a game of baseball. The girls scattered about the playground in smaller groups.

Simmerman had misjudged the proximity of the approaching storm. Only a few minutes passed before the wind kicked up and the first scattered raindrops started to fall. The ballgame continued for another minute. The girls huddled together, but didn’t seek shelter until a sudden downpour caught them off-guard. The boys playing ball and most of the girls ran for the school building, but some of the girls, at least 30 of them, made a dash for the outhouse on their side of the playground.

The outhouse was a whitewashed 10-foot-square frame building. It was positioned over a 12-foot-deep stone vault and located on the east side of the Pleasant Ridge School. The building was 11 years old and had been repaired several times. Just a year prior, the school hired a carpenter to install new seats and replace the flooring and siding. The carpenter presumed the building was sound when he laid the new floor over the old one, which he did without inspecting the joists.

Elsie Schorr, 14, was among the first girls to enter the privy. When she saw how many girls were trying to squeeze into the small, smelly place, she had a vision of a collapsing floor and tried to get out, but the bottleneck on the other side of the door pushed her back inside.

Twelve-year-old Hazel Senour heard someone say, “Oh, what if this would break down with us here.”

In an instant the entire floor crashed to the bottom of the vault…

“The words had hardly come out of her mouth when something happened,” Hazel said. Without the slightest groaning of the wood or tremble of the floor, the joists on one side of the building – sodden from years of moisture – gave way. In an instant the entire floor crashed to the bottom of the vault, carrying with it a crowd of shocked and frightened girls.

There were at least 31 girls – maybe as many as 35 – inside the tiny room when the floor fell out from underneath them. The collapse began on the south side of the building; the floor fell nearly eight feet straight down and disintegrated, churning with the children in a stone vault with a pool of foul water four feet deep. The children were as young as 7.

“Some of the girls were dancing and jumping about when the floor gave way,” said Elsie Ferguson, 16, also one of the first in the building.

“When I arrived there,” said Edna Gerke, 14, “I could hardly get inside the door. I managed to squeeze in, and then before any of us knew of the danger or could get out, the floor gave way.”

“There was no crash at all,” Elsie Ferguson said. “There was no noise whatever. The floor just fell. That’s all there was to it. Not a child screamed that I heard. I felt the floor going and jumped quickly, clutching to the side of the door. I was left hanging to it, and with all my strength I pulled myself up and out of the place.” Five other girls escaped the same way. Some of the girls had climbed up on the toilet seats to make room for the others and managed to hop from one to the other to the doorway.

“There was no crash at all,” Elsie Ferguson said. “There was no noise whatever. The floor just fell. That’s all there was to it. Not a child screamed that I heard. I felt the floor going and jumped quickly, clutching to the side of the door. I was left hanging to it, and with all my strength I pulled myself up and out of the place.” Five other girls escaped the same way. Some of the girls had climbed up on the toilet seats to make room for the others and managed to hop from one to the other to the doorway.

“I remember sinking down and smothering,” Hazel Senour said. “When I found I could breathe again, I just felt like I was awakening from a dream. I caught hold of the stones on the side and held myself up so I could breathe. I felt the soft, struggling bodies of lots of girls around me and underneath me somewhere. They touched me. I could see some heads sometimes and then feet.”

“Everything became dark,” said Edna Gerke. “Everybody was clutching at her neighbor while there was a terrible outcry. I think every girl was crying at the top of her voice. We were all tangled up with each other and struggled to get free. I was pushed about and some attempted to climb up on my shoulders. I made a grab for a stone I could see projecting above my head, and for a moment held on, but there were so many tugging at me that the weight tore my hold loose and I went down. Even then the struggle continued under the water. With desperation I freed myself and looking up saw daylight which I never expected to behold again.”

In the panic that ensued, it became a battle for life, the girls unwittingly pitted against each other for survival as they tried to climb out of the vault and the four-foot-deep pool of waste.

Elsie Schorr and her playmate, Ida Breach, held onto each other on the way down and helped each other stay above the muck.

“The weaker ones were crushed down by the stronger and forced under the mass of filth to their death,” reported the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Lorena Ferguson was just entering the door, standing on the sill, when the floor dropped away right in front of her eyes. Clara Steinkamp, 8, grabbed her dress from behind and kept her from falling in on top of the friends in front of her. After she took a good look at the terrible scene unfolding below, she made a dash for the school to get help.

***

Principal Simmerman said that after the students left the building, he walked across the hallway to speak to one of the teachers.

“A few minutes later two of the little girls ran into the room and exclaimed that a girl had fallen into the vault,” Simmerman wrote in an account published in the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune. “I did not realize the awful calamity that had overcome us, but hurried in the direction of the outbuilding. On the way, I met a number of others. They were screaming wildly at the top of their voices and it was some time before one of them could compose herself sufficiently to explain what had happened.”

Another little girl ran to the high school classroom, which was still in session, and alerted Miss Una Venable of the collapse. She and the four high school boys rushed for the outhouse and arrived at the same time as Principal Simmerman.

No warning from the hysterical girls screaming in the rain could have prepared Simmerman for what he was about to discover. There was only one narrow door to the outhouse. The dozen toilet seats were still attached to the three side of the wall, but there was no floor at all. The sight of the girls – some of them scrambling to climb the walls, others struggling to keep their heads above the sickening waste, and nearly all of them screaming “Help me!” and “Save me!” – caused the principal to stagger back and almost faint.

***

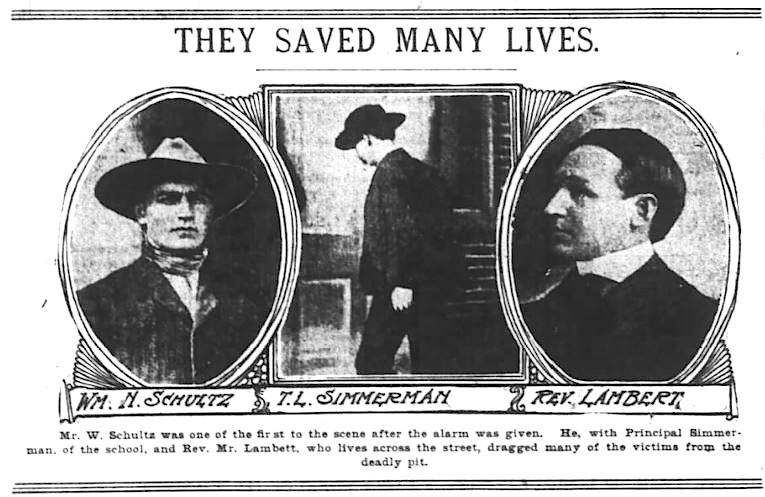

William Schultz, 20, and his friend John Corell, 18, had been across the street in the Presbyterian Church’s manse with Pastor Ira D. Lambert, the town barber Gilright, and a few others when they heard the shrill screams of the girls running away from the outhouse in the pouring rain. The men peered through a window, but could not see anything. As they looked, they began to hear the fainter screams of the girls trapped in the vault. They could make out pleas of “Momma!” and “Poppa!” They looked from one to the other for a moment as the horrible reality of what they were hearing began to set in. Without exchanging a word, the men ran out into the rain and to the girls’ outhouse.

Simmerman was already there in the narrow doorway, “half-mad with anguish,” one of them told the Times-Star. They pushed him aside.

“The horrified men looked down into the pit,” the paper reported. “The surface, dimly seen in the half gloom caused by the outhouse roof, was but a mass of writhing, childish [sic] bodies, which rose and sunk under the filth which had filled the pit.”

Simmerman quickly rallied himself, called out for a rope and ladders, and Miss Venable’s boys leaped into action. Simmerman dropped to the ground and leaned as far as he could over the vault’s edge, but could not reach any of the girls. The men held onto his legs and lowered him down further, and managed to rescue three girls this way before the ladders and ropes arrived. But the step ladders from the school were too short, and the ropes were clotheslines that proved to be as rotten as the privy joists.

“Mr. Simmerman reached down a rope and told me to grab it,” said Hazel Senour. “I wrapped it around my hand and he drew me up pretty near the top when the rope broke and I fell back again. I sank down and a hand pulled me under.”

A second rope broke in the same way. Then James Smith, 16, climbed into the belfry and brought the rope off the bell. It worked a little better and helped save two more girls.

“While I was waiting for a longer ladder,” Simmerman said, “I begged the children to be quiet and brave and I would rescue them.” Some of the older girls took his cue and tried to calm the girls, but it was of little use.

One of the boys found a longer ladder in a barn about 100 yards away, and the principal dipped it into the muck. It was not long enough to reach all the way from the bottom of the vault to the ledge, but it was close enough for Simmerman and some of the other men to descend and lift the girls out of the mess, bucket-brigade style.

The girls were unrecognizable, their eyes clenched shut as they sobbed and gasped for breath.

“As fast as Mr. Simmerman handed up the children I took them and passed them along to others, who carried them to the schoolrooms,” said Miss Venable. The girls were unrecognizable, their eyes clenched shut as they sobbed and gasped for breath.

“The struggle down there was terrible,” said Hazel Senour. “As long as I could get out of the water to take a breath of air, I felt sure of being saved, but when I fell back into the hole, I thought it was all over. The girls about me were grabbing onto me. Everyone grabbed at each other, and when we did get a hold on the wall it was only for a second. I caught hold several times, but when I was pulled at by the others my hand slipped. There were only a few taken out, when I felt something under my feet. It must have been some little girl that had drowned. All the time I prayed. I said my prayers over and over. I could not see after a while and as I was praying to the Lord to save me I found the rake in my hands. When I came into the light, I saw Principal Simmerman. I crawled up and was lifted out.”

After struggling in the crowd with her friends, 14-year-old Edna Gerke again found the jutting stone and gave it another try, “this time with two hands,” she said. “Far above me, it seemed, somebody was coming down a ladder and called to me. Suddenly someone took hold of me. I looked back over my shoulder and saw the agonized faces of my friends, then lost consciousness and knew no more until I woke up in the schoolroom surrounded by the bodies of my friends.” Gerke’s arms were severely bruised and punctuated by deep scratches, wounds she attributed to the clawing attempts of her classmates to climb over her out of the foul water.

The rain abated but the respite in the weather did little to relieve the pandemonium. Many of the girls fainted soon after emerging from the vault, adding fear that they had succumbed to the terrible fumes of the vault to the overall confusion. Neighbors of the school offered their homes as triage centers; rescuers carried them out of the rain and into safety, where they were revived, cleaned up and comforted.

John Steinkamp, a wagon maker in the village who had two daughters in the school – Emma, 12, and Clara, 8 – was one of the first on the scene, running the two blocks from his shop. A few years earlier Steinkamp lost a son when he was struck on the head with a baseball bat, fracturing his skull. Clara ran from a crowd of children and grabbed her father by the hand.

“I’m all right,” she said.

“Thank God!” Steinkamp exclaimed, picking the child up in his arms. “Where is Emma?”

“I don’t know,” Clara said. “She was in there.”

Steinkamp quickly became frantic, trying to force his way in through the small privy door and had to be restrained from climbing down the ladder into the muck to find her. Simmerman told Steinkamp that he was getting in the way and would prevent the girls from getting out.

“But my daughter is down there and she may be dead!”

“But my daughter is down there and she may be dead,” he screamed. He stayed back and watched anxiously as the girls emerged from the outhouse one at a time. He ran to each as she emerged, wiped the filth from their faces hoping to recognize his daughter, growing more frantic and bereft as each fainting child emerged from the horror.

When Simmerman assisted the last girl, the nineteenth, off the ladder and watched other rescuers whisk her off into the schoolhouse, he leaned inside and peered into the dark vault. It was still. All he saw were broken pieces of floor floating on the foul water. His strength began to fade and he reeled. “His face was as white as chalk and he would have fallen had not people come to his assistance,” the Enquirer reported. Simmerman seemed glad the task was over, that all of the girls were saved. Overcome by the noxious fumes and the horror he had witnessed as well as the adrenaline rush of his heroic effort, the principal did not consider that there were girls still in the vault, under the wreckage.

***

William Schultz and John Corell, the two young men with Pastor Lambert, volunteered to go down and search for bodies. Someone gave them each a rake and they climbed down the ladder and waded into the muck. Schultz immediately bumped into the body of Flora Forste and hoisted her up the ladder to waiting hands. She was unconscious, but alive.

John Steinkamp could no longer be persuaded to stay back and began to climb down the ladder. He was so distraught that he could not make it more than a couple of rungs before he climbed back out again. It was clear he was just getting in the way of the rescuers and had to be comforted by a neighbor.

“My girl is in there!” he exclaimed.

“It’s no use, John,” the neighbor said. “You can’t do any good by going down in there. If she is in there, we will get her out. There are too many men down there already. Maybe she is safe. Look among the other children.”

“No!” he cried. “She is in there. She went down with the rest.”

As each body was brought from the darkness, Steinkamp was the first to brush the slime from their faces, and would breathe a sigh of relief when it proved not to be his girl.

News spread fast throughout the village and by the time the rescue had ended, hundreds of parents had arrived on the scene. Many of them, like Steinkamp, were half-crazed and searching for their children, trying to find familiar features on the filthy faces.

The high school classroom became a temporary morgue.

Schultz and his companions would pull nine more little girls from the privy vault. Dr. Ulysses G. Senour, who had come to the scene to check on his daughter and immediately went to work reviving the fainting victims, gave the last nine girls hypodermic injections of nitroglycerin, hoping to give a boost to whatever spark of life may have remained. None of the nine survived. The high school classroom became a temporary morgue as volunteers carried the bodies inside, away from gawking eyes. Sisters Carmen and Fausta Card, ages 7 and 11, were found clasped tightly in each other’s arms and were laid out in the classroom just that way. Fausta’s twin, Rotha, was with her sisters when the floor collapsed, but managed to keep her footing and stayed on top of the pile.

Emma Steinkamp was one of the last bodies to be removed.

“It’s my girl,” cried the grief-stricken blacksmith. “Poor Emma! She left home this morning in the best of spirits. I never expected to see her brought back like this.”

It took some effort to persuade Steinkamp to give up the body for the temporary morgue, but once he did, he went back to the scene and began to help other parents find out what had happened to their children.

By then it was 12:30 p.m. and the sun was shining. Hamilton County Coroner Walter B. Weaver arrived in his automobile. The crowd swelled as relatives began streaming in from downtown Cincinnati. It had taken about an hour for newspaper accounts of the collapse to reach the broader community. Word spread quickly and Pleasant Ridge residents who worked downtown ran for the two trains that led to the village, where they met the frantic children and mothers of the victims, pacing in front of the school.

Stella Corell and Flora Forste were removed to Dr. Senour’s, home. Stella was vomiting blood and Dr. Senour was not sure she would live. Rescuers took the other 19 children to neighborhood homes, but no one kept a roster of who had been pulled from the vault and where she went. Frantic confusion continued for several more hours as more and more people arrived from nearby villages, especially Rossmoyne, although most of the girls who crammed into the privy lived in Pleasant Ridge. The routes between the school and the train stations were crammed with people. The village’s telephone system proved inadequate to keep up with the demand, and hundreds of people crowded around every available phone, waiting a turn.

When the adrenaline rush of the rescue abated, Principal Simmerman and his teachers sobbed along with the parents who lost their daughters. Dr. Senour looked at the exhausted and emotionally distraught principal and ordered him to a house across the street to rest. Dr. Senour remained there the remainder of the afternoon, suffering from a severe headache brought on by the tension and the hours he spent inhaling the noxious fumes of the privy vault.

When the last body had been removed the village fire department began pumping the filth out of the vault. After examining the nine little bodies on the classroom floor, Coroner Weaver investigated the outhouse. It only took a glance. “Rotten, rotten, rotten,” were his first words. “Everything was rotten. Those joists would not hold anything.”

By this time, the sun had come out. Weaver ordered the firemen to haul the pieces of broken flooring out to dry. One reporter stuck the point of his umbrellas clear through a six-by-two timber. With their fingers, people pulled off big, rotten splinters from the ends of the boards where they had been grooved to attach to the sides of the vault. Weaver gave instructions to take the pieces into the school’s basement and locked away until his investigation was complete.

John Steinkamp remained on the scene, no longer frantic and helping in whatever capacity anyone would let him. Earlier that afternoon, he had spotted his wife and all seven of their surviving children in an anxious group near the school building. Their affection and attention was focused on Clara, who was one of three girls standing on the threshold when the floor collapsed and barely escaped plunging into the foul water herself. The wagon maker approached them in tears, crying out, “My god, there are only seven now!”

By the time night fell, at least three different funds had been started to pay for the nine funerals and assist the families of the victims. The entire city of Cincinnati responded, especially those communities bordering on Pleasant Ridge. The wife of Mayor J.J. Marvin proposed the purchase of a shaft of pure marble to be erected in the schoolyard to represent the “pure, carefree, innocent lives” that were lost.

David Fisher, the local Ohio Inspector of Factories, Workshops and Public Buildings said that his office was not required to make inspections of school buildings unless there was a complaint; thus he had never made one. He had recently inspected the outhouses and ordered repairs at Silverton and Arlington Heights and had condemned the school building in Rossmoyne, but had never gotten a complaint about Pleasant Ridge. He was the only inspector in Hamilton County, and his time was dominated by the factories, for which complaints were legion. He told the Enquirer he was surprised that the school had a vault, since Pleasant Ridge had a sewer system.

The village council canceled its regular meeting that evening because of the tragedy, but the Board of Education convened in the home of its president, the Rev. Fred Hohmann. The meeting was as solemn as a funeral. The five attending members, with one absence, issued a statement that seemed to do nothing more than dodge responsibility: “The Board had done all that was humanly possible to keep the building in a safe condition, having no intimation in any manner of any danger coming to the Board or any member of the Board or to the superintendent or to any one of the teachers. It had been frequently and so far as was possible thoroughly inspected and to our best knowledge no foresight could have prevented this tragedy.”

During the reading of the proclamation into the minutes, Simmerman sat with his hands covering his face, sighing frequently. The Board voted to close the school for at least a week, saying that in all likelihood it would remain closed until new “accommodations” were built. It would not reopen until October 10.

The Rev. Hohmann said that for the past six years he had never missed testing the floors of the outhouses by jumping upon them with his own 200 pounds, and had done so just a month ago. Principal Simmerman said that hardly a day passed when there weren’t 40 girls in the privy at any given time (although, given that the room measured only 10 feet by 10 feet, that seems hard to fathom). He said he frequently inspected the restrooms, looking for graffiti, and never noticed any weakness in the floor.

The board adjourned after deciding to build another outhouse with a drain vault. This time, it would not be over three feet deep.

On the day after the collapse, Henry Swift – an old bearded fellow who had been the janitor at Pleasant Ridge from 1884 until 1903 – went to see Constable Louis Haerr, the coroner’s investigator. Swift said that in April, 1903, he went into the girls’ privy to sweep up and noticed a gleam of light down in the vault. Looking closer, he noticed that the stone wall on the west side of the vault had bulged and some stones had fallen out, making a hole about two feet in diameter a foot or so above the ground where the privy had been built on a slope. Swift said he at once notified Principal Simmerman, who sent him to see the Rev. Dr. Hohmann of the building committee. Hohmann told him to place some planks in front of the breech until he could arrange to have it repaired.

So he did, and he continued to work at the school through the summer vacation, before taking a job at the Kennedy Heights School. “At the time I left those boards were still in position and the repairs had not been made. When I went away, fearful that the flooring had been weakened, fearful that on account of the missing stones the building would collapse, I nailed boards across the entrance. And I did not use ordinary nails, I used spikes.”

Swift said that he had been fearful for some time that the building would collapse. The floor seemed solid enough, but the foundation was crumbling.

State Inspector Fisher visited the scene with consulting engineer Ward Baldwin and both declared it a wonder that such a catastrophe had not happened long ago. The coroner had placed the scraps of joists and flooring under lock and key in the school basement, and when Fisher saw them, he was flabbergasted.

“My lord, they ought not to have used yellow pine for those joists!”

“My lord, they ought not to have used yellow pine for those joists!” he exclaimed. “That building had been unsafe for a long period. Gases and water in the vault would rot pine easily. Red cedar ought to have been used. Iron girders ought to have been used. This building has been unsafe almost from its erection because the girders were insufficiently fastened on the framework.”

In fact, he said, the entire construction plan was faulty, relying on one big joist to hold up the weight of all the others. Fisher condemned the boys’ outhouse without a direct inspection of its joists, presuming that since it was built at the same time as the girls’, it was likely in the same condition, and he would take no chances.

***

On Sunday morning, the church bells of Pleasant Ridge rang continuously from 9 a.m., when the first funeral started, until 4 p.m., when the last of the four girls buried that day, Hazel Glover, was put to rest. Four female schoolmates of Emma Steinkamp, the first victim to be buried, had been tapped to be her pallbearers, but after carrying the casket to the front of the German Evangelical Church, the girls were too grieved to manage more, so four boys took over. The girls, dressed in white and bearing flowers, walked alongside. John Steinkamp and his wife were so stricken that they had to be led into the German Evangelical Church, followed by their seven surviving children, while the choir sang “Nearer My God to Thee.” Pastor Hohmann and the Rev. Harmann of the Methodist Church both tried to calm the sobbing crowd. The Steinkamp grandmother fell weeping against the small casket and Emma’s mother fainted with a deafening shriek. At that point, two of the girls in white became hysterical and their parents carried them from the scene. The entire town and a fair portion of the rest of Cincinnati followed the hearse to the cemetery.

The Presbyterian Church hosted back-to-back funerals starting at 1 p.m. when a white hearse pulled up to the front doors with the body of 10-year-old Edna Thee. A choir sang “Safe in the Arms of Jesus” while four boys carried the flower-laden casket into the sanctuary.

The funeral of 9-year-old Emelia Hesse took place without much ceremony at the home of her parents. Except for the Card sisters, who were cremated, the girls were all buried in the Pleasant Ridge Cemetery just across from the school. With its shaded lanes and parklike atmosphere, it was a favorite place for the children to romp and play after school.

The town was overrun by sightseers, “the schoolhouse yard black with humanity,” the Enquirer reported. Although there were boards nailed across the privy door, people leaned over the barricade and dropped burning bits of newspaper into the vault to get a better view of its gruesome depths. Many approached the vault with a jaunty, curious air, but invariably turned away with an expression of shock, many in tears. All day long, people pointed at a pile of filthy clothing that had been removed from the girls until a random fellow gathered them up in a bundle and took them into the woods to set them on fire.

The murmur among the crowd was that there should be an investigation, and Coroner Weaver’s name came up most often. Members of the school board emphatically denied custodian Swift’s charges, saying that the broken wall had been repaired immediately. Further, they noted it was his own brother, John Swift, who laid the foundation for both of the school’s outhouses. Popular sentiment seemed to favor Swift.

“After an accident of this kind everyone wants to make snap judgments,” said Board member Lewis Brewer, “and no one wants to put himself in your place. I have heard many words of condemnation for our board, have even heard persons on the cars say we ought to be hung, but I think that’s passing over now.”

Sunday morning, Dr. Senour tended to Will Schultz, the young man who led the effort to recover the bodies. Schultz was having severe pains in his lungs. The doctor said it was the ill effects of inhaling the fumes of the vault and that it should pass. Dr. Senour was so moved by Schultz’s bravery and sacrifice that he began taking subscriptions to purchase a set of four medals to be presented to him and the other young men who went into the vault after the bodies.

“While the citizen are speaking about helping the families of the dead, have they forgotten the four men who in the hour of need proved heroes?” he said. “It seems to me these men have come in for a little consideration now that the excitement is cooling off. Nothing under God’s sun would have induced me to go down into that awful pit Friday, but the sight of my daughter, yet these men entirely disinterested in the girls struggling below, plunged into the vault and with Spartan heroism saved so many lives.”

The mayor’s fund to erect a marble marker had already accumulated over $1,000 by then, but Miss Una Venable approached Mayor John Marvin to voice the objections of the teaching staff. She claimed such a marker would be a constant, unwanted reminder of the calamity, and suggested a more subdued stained glass window for the school building. Mayor Marvin’s wife then suggested a marble shaft in the cemetery across the street from the school instead. The mayor demurred and said that he would call a meeting on the matter. He didn’t need to. On Monday evening, after the last of the funerals, an impromptu indignation meeting popped up around the mayor’s house over the matter. Some of the men who had given over $100 each were opposed to any kind of memorial. They had donated the money to pay for the girls’ funerals since many of the families were quite poor. If there was a surplus, it should be divided among them. Others cautioned that offering money to the victims’ families might seem like trying to pay them off. At first, the mayor demurred again, saying that he would hold a proper meeting on the matter on Wednesday, but by 9 p.m. so many people had gathered that he announced he would follow the wishes of the major subscribers to the fund: To pay the funeral expenses and medical bills for all of the girls and divide the remainder equally among the families of those who died.

An indignation meeting also sprang up in Rossmoyne. There, the citizens nominated a slate of candidates to oppose the current board for the upcoming Board of Education election in hopes of passing a bond issue to build a new school.

Coroner Weaver opened the inquest on Monday morning, but had time to hear from only four witnesses owing to his backlog of cases. The first witness was one of the girls who was in the privy at the time of the collapse. Then the janitor Henry Swift told of the bulging wall, and John Steinkamp complained that Simmerman and the others at the scene waited too long to begin the search for bodies. When the last girl climbed out, Simmerman and others presumed that everyone had been saved, and it was only because of the protests of his daughter Clara saying that Emma was still inside that they searched for the dead. The 10 minutes that passed could have been critical, he said. Steinkamp also said that his daughters told their mother that the floor was rickety the first week of school. “I did not learn of this until after the accident,” he said. “I have also since learned from my daughters that about a year ago the floor was in such a bad condition and one of the girls had a narrow escape from falling through. They fixed the floor then, I understand.

“It is carelessness to build such a building and such a deep vault and leave so much filth in it,” he said.

The final witness was Silas V. Cliver, the carpenter who had put in a new row of seats the previous year. In doing so, he took up 15 inches of flooring, but noted the condition of the joists. He had apparently been taking a lot of heat from the residents of Pleasant Ridge, so he asked to make a statement.

“I want it thoroughly understood that I did not build that floor,” he said, but had only been hired to make some alterations. “You will never find out who laid the so-called new floor because I never heard of one being laid.”

Early the next week, the Hamilton County Board of Health took up the privy issue and ordered that every outside vault connected with a public school building be immediately inspected and then inspected regularly thereafter. They also adopted a resolution ordering the Health Department to make immediate arrangements to connect every vault with a trunk sewer wherever possible. On Monday, the president of the Cincinnati Board of Education and the superintendent began a personal inspection of the district’s outhouses.

The coroner did not take up the case again until October 3, when he saw more witnesses: Will Schultz, John Carrell and Inspector Fisher, who said that the incident has been getting attention from inspectors all around the state. They were seeking an opinion from the state attorney general about whether inspectors should be required to inspect vaults.

Only a few of the girls who had been rescued from the depths of the vault sustained serious injury. In spite of the eight-foot freefall, none of the newspapers reported any broken bones. Several girls suffered bruises and cuts on their arms and legs, some of which became infected later. It was touch-and-go for Stella Corell and Flora Forste for a week or so, but both recovered, as did the hero William Schultz.

Coroner Weaver issued his verdict on October 19, citing suffocation as the cause of the nine deaths and declaring gross negligence on the part of the Board of Education.

“The accident occurred on account of the decayed condition of the joists supporting the floor covering of the vault,” his report read. “The floor was in such condition as to indicate that it had been laid when the joists were in a state of decay.”

No charges were ever filed nor indictments issued. The village of Pleasant Ridge relieved their indignation in a democratic fashion. The Board of Education election that November included none of the incumbents, deferring to a “Citizen’s Ticket” of nominees. Board members maintained to the end that in spite of the coroner’s ruling, there was nothing they could have done to foresee or prevent the privy disaster. Hohmann said they did not want to seek another term if they had to fight for it. It’s also likely that they could not muster enough support for a nomination.

—

Sources:

Cincinnati Commercial Tribune: “Nine Children are Killed at Schoolhouse,” September 23, 1904; “Shaft Will Rise in Honor of Dead,” September 25, 1904; “Little Victims of Tragedy are Laid to Rest,” September 26, 1904.

Cincinnati Enquirer: “Rotten Timbers Gave Way and Thirty Children were plunged into the vault,” September 24, 1904; “Gloom Over Pleasant Ridge,” September 25, 1904; “Bells Tolled Sad Requiem,” September 26, 1904; “Last Sad Scenes Enacted,” September 27, 1904; “No Nails Used to Fasten Joists,” October 4, 1904; “Gross negligence responsible for Pleasant Ridge School Horror,” October 20, 1904.

Cincinnati Post: “Nine School Girls Killed in Awful Pleasant Ridge Accident,” September 23, 1904; “Tour of Inspection of All of the School Buildings has Begun,” September 24, 1904; “Incidents in the terrible tragedy at Pleasant Ridge School,” September 24, 1904; “Coroner begins Investigation into Pleasant Ridge School Calamity,” September 26, 1904.

Cincinnati Times-Star: “Horror at the Public School of Pleasant Ridge,” September 23, 1904; “Death Trap for Pupils for Years,” September 24, 1904; “Begins inquest on Horror,” September 26, 1904.

—

After 25 years as a writer and editor for the Hamilton Journal-News, in 2013 Richard O Jones gave up the grind of daily journalism for a life of true crime. His first book, Cincinnati’s Savage Seamstress: The Edythe Klumpp Murder Scandal, was published in October, 2014, by History Press. He is also the publisher of Two-Dollar Terrors, a series of novella-length true crime stories, and keeper of the blog True Crime Historian.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at $5 per month.

My name is Michael Rich of Carmichael, California. I was conducting a general web search regarding my family, when to my surprise, I came across your article about the Pleasant Ridge School privy disaster. This event haunted my mother’s family for decades and I grew up with the story. John Steinkamp (1868-1940) was my maternal grandfather. My mother, Helen Emily (nee Steinkamp) Rich (1912-2003), was the youngest and last child of John Steinkamp and my grandmother Sophia (nee Eggerding) Steinkamp (1868-1942). Clara Steinkamp was my aunt; she passed away on March 16, 1964. Your article provided a vivid description of the events on that fateful day in 1904 as well as a description of my grandfather’s actions and statements. I was not aware of all of the factual details including the causes of this disaster.

I would like to provide some corrections: The child my grandparents lost that day was named “Emily,” not Emma. (My mother was given the middle name of Emily in honor of their deceased child.) My grandfather’s full name was John Christian Steinkamp, not John B. Steinkamp. (Not to be confused with John B. Steinkamp the Cincinnati architect.) I was not aware of a son who died from a baseball bat head injury. The only sons I have ever known about were my uncles Frederick Steinkamp and Edward Steinkamp. I would appreciate any information concerning another son.

Thank you.

Great story.

Was glued to it until it was finished.

.

Jeff smith

Hamilton ohio

Jeff, I couldn’t stop reading this either. I had never heard this before. How sad. I can’t imagine what those girls went through. Michael Rich, did you ever find

out if your grandparent’s had a son that died from a baseball bat injury.