By Adam Hartzell

When it came time for me to play football in eighth grade, I didn’t have any idea what position to play. I grew up dreaming of diamonds, not gridirons. I wanted the walk-off home run, not the touchdown, the leaping catch above the back fence, not the interception in midfield.

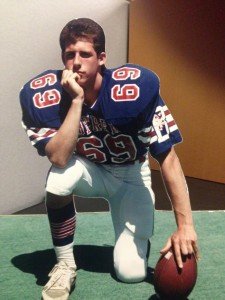

But growing up in Berea, Ohio, in the 70s and 80s I was a male of a certain size and build, and football was expected. Much to the dismay of a friend who had his eyes on the position, I was placed at center and I would stay there. I started each year, from eighth grade to high school varsity. We were undefeated until my sophomore year. Our first loss happened when I was sidelined due to lower back issues, a condition that has continued to plague me. I like to claim we lost because I wasn’t playing, but I know that is bullshit.

During my early years as a Berean, the Browns’ headquarters were across from Berea High School and those humble headquarters looked like an insurance office, nothing like what you see in the Kevin Costner vehicle, Draft Day. (You know, that film supposedly based in Cleveland where characters who were reared in Cleveland anachronistically call pop “soda.”) There’s a shot in that film of the latest Browns’ headquarters in Berea that sits on annexed land formerly part of neighboring Brook Park. The Browns regularly practiced at the Astroturfed George Finnie stadium of Baldwin-Wallace College (now University), the same field where our varsity played beneath Friday night lights. Before moving up to what you saw in Draft Day, the Browns had their headquarters next to Finnie, an upgrade from the previous insurance office. I still remember the Browns players holding signs out on East Bagley Road while heading to school during the NFL players’ strike of 1987.

Although I fell into the position of center, I took my role seriously. I enjoyed pulling off a successful block. I relished pushing my opponent way back, forcefully. Keep in mind, back then it was against the rules of our conference for the offensive line players to use their hands. It was all shoulders and head, torso, and legs. I overheard from people who knew more than I about the strategic intricacies of the game that they were impressed with my performance, which is likely why I started all the way up to varsity. But after my left elbow was dislocated on a goal line drive in the fourth game of my senior year, I was out for the rest of the season. It was one of those flukes of a play. I swear we had scored on the previous drive, but the refs claimed we hadn’t. On the proceeding one-more-time-with-feeling play on the inches of a yard line, I braced myself on the ground after I sent the nose tackle back. Our running back proceeded to come down on my elbow. Thankfully, my elbow popped itself back in the course of the play. I, however, wouldn’t pop in to play in any future football games.

In some ways, though, I was done with football that summer before the season even began.

[blocktext align=”right”]In some ways, though, I was done with football that summer before the season even began.[/blocktext]Before state or conference rules allowed us to begin two-a-days, we met on the practice field for conditioning. A couple summer nights a week we ran sprints, we jogged, and we did jumping jacks, sit-ups, and push-ups to get us in shape for the coming year. During the first of those pre-two-a-days my senior year, we discovered a girl was trying out for the team.

I didn’t know this girl well, but I’d seen her before. It was a fairly small school where you knew everybody by sight if not by name. Her body was totally appropriate for football. Remember, this was before kids started to take steroids or even protein powder to bulk up. This girl’s body presented as someone who could work on the offensive line considering the size of boys at that time. Hell, if she could master the long snap, something I continued to have trouble with, she might have taken over my position.

Our coaches did not forbid her to try out. They just changed the rules. We never, ever, did stairs during these summer drills. It was mostly calisthenics. The worst we did was that drill where you run in place and then a coach yells to have you hit the ground. (I’m sure there are different regionalisms for this drill, but in Gregg Easterbrook’s excellent The King of Sports: Football’s Impact on America they are called simply “up-downs.”)

Sure, such conditioning might be tough, but there’s no reason the average high school girl or boy couldn’t survive the drills. The state or conference rules were that you couldn’t suit up and you couldn’t hit the pads or hit others. These weren’t drills intended to weed people out like an athletic variant of a pre-med class. The tougher drills – like the stairs – would come later during two-a-days.

Sure, such conditioning might be tough, but there’s no reason the average high school girl or boy couldn’t survive the drills. The state or conference rules were that you couldn’t suit up and you couldn’t hit the pads or hit others. These weren’t drills intended to weed people out like an athletic variant of a pre-med class. The tougher drills – like the stairs – would come later during two-a-days.

But since she was there where she wasn’t wanted, they had us running stairs up and down one of the crappy stand sectionals that sat along the practice field, where spectators sat developing hemorrhoids during the JV and freshman games played on the field on Saturdays. These rickety stands were as sturdy as the argument the coaches were making.

Sadly, this ruse to maintain the foundation of male supremacy worked. She couldn’t hack the stairs. At the end of the practice, she gave a teary speech saying she wasn’t going to try out for the team after all. We applauded her for trying.

This was all a show. As I would learn later, this is what fire departments and other formerly male-only professions used to do to keep women out. Sure, you can try out. We’ll just make you work twice as hard. We’ll just keep you outside of the networks that enable you to understand what you need to know to pass the tests. We will punish you until you decide, on your own of course, that you can’t handle it.

Thing is, there were a few guys who couldn’t handle it that night either. Yet they stayed on. They likely knew every practice would not be this hard. Personally, I wanted to throw up after that practice. From exhaustion, yes, but also perhaps thanks to what I had just witnessed. I wanted to throw up from being an accomplice.

[blocktext align=”right”]I didn’t speak out on the girl’s behalf then. I didn’t rock the ship of the S.S. Macho. I kept my mouth shut.[/blocktext]I didn’t speak out on the girl’s behalf then. I didn’t rock the ship of the S.S. Macho. I kept my mouth shut. When two-a-days began, I practiced hitting hard so I wouldn’t be called a girl by the coaches. I went along to maintain the privilege that comes with being a future man. I saw what they did to outsiders. I saw how I might be perceived if I hadn’t won the genetic lottery and been given the build that announced I played football.

But something still churned inside. It added context to a pep talk by one of the coaches where we were told how much better we were than the other kids who didn’t play football. We were told we should hang out only with fellow players. These other kids against whom the coach railed were my friends, kids who cared about academics over sports. I knew what coach was trying to do. He was trying to bond us by making us think we were superior because we were built to play this game in a certain way. He was trying to cleave us together by cleaving us from other kids deemed as lesser. These other kids, like that girl who dared to try out, that girl who represented all girls, that category “girls” including boys who didn’t fit the masculine mold, those other kids were losers to their definition of winners.

Again, I thought the pep talk was bullshit. Again, I said nothing. I also said nothing about how wrong it seemed that we’d say the Lord’s Prayer in the locker room before heading out to the field before games. We were a public school. We had a Jewish kid on the team.

For Christ’s sake. But though I said nothing in those moments, I spoke by my future actions. I chose my university partly because sports weren’t a major factor there. I chose my university partly on seeing folks in libraries and other study areas on the weekend. How awesome was that?

Thankfully, this university chose me too. My first plane ride ever was to visit the campus, something my folks only allowed after I was accepted. Thankfully, my dream school provided the best financial aid package of all the schools to which I applied. I could actually attend. I could leave Berea. I could leave Ohio. I could leave football behind.

I have never followed college football and now that I understand how heavily college programs are publicly subsidized as a de facto minor league for the NFL, I can’t start. Given the scandal fairly specific to the NFL (concussions) and those scandals not unique to the NFL (domestic violence and wage theft), plus the hold-no-punches arguments put forward by Oakland Raiders fan Steve Almond in his book Against Football: One Reluctant Fan’s Manifesto, I can’t even get into the NFL much anymore, not that, as I mentioned at the beginning, I was much of a fan to begin with.

As much as Cleveland fans can bond as a community over our sports misery, sports, I believe, are not all about community. It’s interesting that when folks consider past Cleveland championships, the Cleveland Crunch is excluded. What the world calls football and we (and Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) call soccer is not seen as a true sport by many in the US. It isn’t deemed manly enough. Soccer is excluded from what matters in the life of the so-called average sports fan, just as that girl was excluded from my team, just as my friends in the halls of my high school were excluded from my team, just as a Jewish kid had to sit through a recitation of Christian devotion.

This awareness of how sports ostracize community members as much as they embrace is why some of us fans of Cleveland’s baseball team won’t wear anything with Chief Wahoo on it. We see how that racist caricature excludes through mockery, through the team’s refusal to listen to the Native American community.

Mark Winegardner begins chapter four of his epic Cleveland novel Crooked River Burning noting how the word ‘cleave’ is an antonymous homonym. The word means its opposite, and how appropriate is Cleveland itself is as an antonymous homonym? We should return that second ‘a’ in the spelling of Cle(a)veland to underscore this. If a land cleaves, it could be conjoining, it could be separating. The hard part of our Cleveland sports fandom – and all fandom – is to confront the aspects that end up separating us from our fellow Clevelanders, our sister fans. It is in those moments of cleaving as severing that sports are not demonstrating the best of our nature. They are demonstrating the worst of our nurture.

Adam Hartzell grew up in Berea, Ohio. He has been a contributing writer at Koreanfilm.org since 2000. He has written for various other websites (Fandor, sf360, VCinemaShow, APG Sports), the quarterly magazine Kyoto Journal, and has a chapter in The Cinema of Japan and Korea (Wallflower Press) along with contributions in the book Director of World Cinema: South Korea (Intellect Ltd). He writes often about the films of Hong Sangsoo such as for a retrospective of his work held in San Francisco and for a recent panel on Hong for the Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Seattle in 2014.

Support paywall free, independent Rust Belt journalism — and become part of a growing community — by becoming a member of Belt.

Thanks for writing this, and so well. It’s an important restriction on access ignored by virtually everybody — including those who call themselves “feminists” — that I think the future will rightly see as shameful.

We’ve already settled that “separate but equal” isn’t how we as a society want to run our schools, buses, and drinking fountains. Why our sports teams? That’s not to say that women will become a majority (or, probably, even common) on teams where size is a benefit — football and basketball come to mind. But there’s no reason they shouldn’t have the right to prove themselves in the same manner as men.