The following text and photos are excerpted from Out of the Kokoon, by Henry Adams, with Lawrence Waldman (Cleveland Public Library, 2011):

Cleveland vies with Seattle for the title of the grayest, most overcast American city, and in the first three decades of the 20th century it was even grayer than it is now, for steel mills and factories, then roaring at full capacity, belched great plumes of smoke and grit that darkened the air. It was a conservative city as well where both executives and factory workers dressed in drab colors, and labor and discipline were the order of the day. Saturday was still a work day and Sunday was reserved for going to church.

But once a year, between 1911 and 1938, the lid came off for a festival of dance and color: the Kokoon Klub Ball. Even today there are legends of the revelers who came to dance, some in bright costumes and some dressed only in talcum powder — or less. Indeed, a little research quickly establishes that these legends are rooted in fact, for scrapbooks survive from many of the balls filled with photographs of the celebrants. These record hundreds of attendees who arrived in costumes worthy of the Ballets Russes, as well as a courageous few who wore only body paint.

Shock value was clearly part of the delight of the evening. For just one night a year Cleveland forgot that it was Cleveland and became a bachanallia held in some exotic far-away place, preferably one with relaxed morals, such as the Latin Quarter of Paris, the Sea Palace of Neptune, the Pharaoh’s court (“It’s nice to be the King”) in ancient Egypt, or the Persia of the Arabian Nights. But to view the event as just a debauch is to miss its deeper purpose. Interestingly, it was in good part through the Kokoon Klub and its annual ball that Cleveland — and because of developments in Cleveland much of the rest of America as well — was seduced into a love affair with modern art, and was persuaded that while such art might well be a bit crazy, a bit mentally unhinged, it was also eye-catching, invigorating, and fun.

Today the glorious posters of the Kokoon Klub (they’re reminiscent of the work of Leon Bakst, but with an American accent) have quietly become some of the most sought-after graphics of the ‘teens and ‘twenties, and are starting to fetch big prices. But as it happens, this is only part of the story. For what’s fascinating is how, in the space of a decade or so, the members of the Kokoon Klub not only changed the artistic taste of a city but had a wider impact.

The Kokooners pumped color and life into the work that local painters showed at Cleveland art galleries and in the annual May Show at the newly opened Cleveland Museum of Art. They established a taste and a market for a sort of modern art that has been considered crazy only a few years before. More broadly, they reshaped the look of movie posters and billboards and advertisements, both locally and nationally, transforing American visual culture for an audience of millions. Color is the word that comes up repeatedly in accounts of the Kokoon Klub. Before the Kokoon Klub the art of the American Midwest came mostly in shades of brown and gray. After the Kokoon Klub did its work, the heartland had adopted the colors of the peacock and the rainbow.

The Birth of the Kokoon Klub

By the turn of the century Cleveland had become one of America’s greatest centers of printing — and while exact figures aren’t available, it seems to have had a volume of printing that surpassed even New York. The reasons were manifold but one was particularly telling: in an age before digital communication, when a print run was managed from a single place, Cleveland was ideally situated for distribution to the rest of the country. The birth of the Kokoon Klub was due to a specific event in this evolution.

In 1908 the Otis Lithograph Company, which had until then specialized in theatrical posters, landed a gigantic contract to produce posters for a new entertainment medium that was replacing vaudeville — the movies. Specific numbers are hard to come by, but in 1913 Otis published 3 ½ million posters for a single now-forgotten movie titled The Battle of Waterloo. By that time the plant took up four entire city blocks. We know that by the late 1920s the Cleveland company had the capacity to produce up to 55 million posters a month.

At the time, while they were often based on photographs, movie posters were drawn and colored by hand — drawn freehand with a crayon on a lithographic stone. To do this work required extremely skilled artists and craftsmen and it was clear to the management that if they were going to keep their contract with the movie studios they needed to maintain the highest possible technical and artistic standards and hire artists and craftsmen who had the ability and talent to achieve them.

Consequently, the ink on their new poster contract hardly dry, the management at Otis launched a corporate raid. They went to New York and hired away from the J. Ottman Company, New York’s leading lithography firm, two of the nation’s most gifted and experienced poster artists — Carl Moellmann and William Sommer.

Carl Moellmann, who was originally an Ohio boy, was the manager at the Ottman Company. He was also closely associated with the first major modernist group in 20th century American art, the Ashcan School, the group of urban Realist artists who were at the center of the first major artistic success du scandale of the 20th century: the 1908 show of “The Eight” at the Macbeth Galleries in Manhattan. It was Moellmann who introduced the various members of “The Eight” to lithography, and he appears in a humorous print by John Sloan, Amateur Lithographers, in which he and Sloan are shown straining and huffing and puffing as they run off a lithograph on a small press together.

Along with Moellmann came his most gifted draftsman, William Sommer, who became one of the leading Cleveland modernists. When he came to Otis in Cleveland it was in part with the understanding that he would introduce a bolder, freer, more modern look into the lithographs they produced — make them more up-to-date and more visually arresting. As a lithographer Sommer was renowned for his virtuosity, particularly the skill with which he could produce the outline of a face or figure with a single, confident, flowing line. But he was also an alcoholic. His working relationship with Moellman was predicated on the understanding that periodically, after working faithfully and steadily for months, he would simply disappear for a week or ten days on a drinking binge and then return when it was over.

Moellmann and Sommer were the principal initiators of the Kokoon Klub, which held its first meeting in the summer of 1911, and officially formed in August, with Moellmann as President and Sommer as Vice-President. A 1911 article in Cleveland Town Topics announced the creation of the venture. Its principal goal was simply to provide a place where artists could hold drawing sessions from the model, and more generally to encourage interest in art and modern art. Most of the members were commercial artists rather than teachers at the local art schools. In fact, they specifically wanted to avoid the teaching available in local art schools, and draw in a freer and more modern way on their own.

The model for the venture was the Kit Kat Club in New York. Moellmann came up with the idea of using the word “Kokoon,” to symbolize an awakening: to celebrate the emergence from cocoon to butterfly of both the artists in the club and the city of Cleveland.

The Secessionists.

Throughout its history the Klub was associated with modern tendencies and its founding in 1911 was no accident. It coincided with the emergence of Cleveland’s first organized group of modern artists, which was in turn associated with the first appearance of radical modernism in Cleveland just a year before.

In 1910, Abe Warshawky, who had grown up in the city, returned to Cleveland from France with a group of brightly colored Impressionist works, including some that had been executed with a palette knife. While hardly very radical by the standards of today, for the Cleveland of that time, accustomed to the dark “brown sauce” of the Barbizon painters or the denizens of the Munich School, they were revolutionary and shocking. Clevelanders had never seen anything like them. Henri’s style, with its vigorous brushwork, which had already been taken up by Sommer and Moellman, was also radical for the time. But it was not radical enough to cause a scandal: it was Warshawsky’s work that first produced Cleveland’s first true art scandal.

The members of the Kokoon Klub quickly took up Warshawsky’s radical color schemes, and organized themselves into a group called The Secessionists, exhibiting their work at the Kokoon Klub as well as at Louis Rorimer’s gallery.

But things quickly took an even more radical turn. In 1911 William Zorach, who had taken leave for a year from Otis to study in Paris, came back to Cleveland with reports of the paintings of Matisse. In 1912 another young Cleveland artist, August Biehle, came back from Munich with a catalog of the work of the modernist Blue Rider group. And, finally, in 1913 William Sommer attended the landmark Armory Show in Chicago, America’s first large-scale exhibition of modern European art. In 1913 there was even a display of Cubist paintings, “straight from Paris,” at the Taylor Department Store.

These new developments were eagerly taken up in Cleveland. As early as 1912, at an exhibition of the Cleveland Secessionists at the Taylor Galleries, according to contemporary reviews, visitors engaged in arguments about Matisse while examining the paintings. At the model-drawing sessions of the Kokoon Klub, William Sommer began to emulate a technique that had been developed by Matisse, of drawing with a matchstick dipped in ink. By 1913, Cleveland had a small group of artists, all members of the Kokoon Klub, experimenting with Fauvist, Cubist, and Futurist techniques. Probably in no other city outside of New York did a group of American artists embrace modern styles so eagerly and so early. Almost all of these apostles of modernity were commercial artists, many of them employed by Otis, who produced modernist work in their free time.

Indeed, the teachers in Cleveland’s established art schools, led by Frederick Gottwald, were more conservative, and formed a rival group, the Cleveland Society of Artists, to promote “sanity in art.” Tempers sometimes flared. Charles Burchfield, then a young art student in Cleveland, and a protégé of Gottwald’s rival, Henry Keller, recalled that, “We even heard rumor of fist-fights at exhibitions.”

The Bal Masque

Throughout its history, the members of the Kokoon Klub held auctions of their work, but these were never very successful, and the paintings sometimes sold for less than the cost of their frames. Indeed, the low prices became a running joke. One president of the Klub, Ignace Walasek, told a reporter that a coming auction provide “a great chance for people who sincerely hate modern art. They can come and buy it cheap and burn it up.”

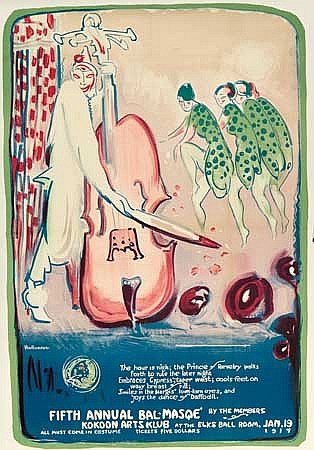

In its second year, 1913, the members decided to throw a costume ball in the old Elks Club as a fundraiser. After the costumed guests had arrived the lights went out and a dim spotlight gleamed on men clad only in loincloths who bore a giant cocoon through the throng, guided by the president of the club, Allen Earnshaw, dressed as Mephistopheles. They deposited the cocoon on the stage, cymbals clashed, and a girl popped out, dressed principally in a pair of butterfly wings. She performed a dance, and then the spotlight focused on Mephistopheles, who delivered a brief speech describing the night ahead, and reminding the participants of their duty to forget the conventional world and to let go in complete carnival. At the time long skirts and prudery were the mode; the wildest dance in vogue was a waltz. This was clearly something different. Next day the party was the talk of the town.

When receipts were counted, it turned out that the first ball had lost $1, but it created such as stir that attendance ballooned the next year, and by the mid-1920s attendance had grown from about 200 to well over 2,000. While artists held balls in other places, no other city staged an event that was so colorful, so artistic, and so provocative. The party was always scheduled on Friday, since it went on till well after midnight, and if it had been held on Sunday this would have been prohibited by the blue laws. Often the entertainment had a humorous quality in tune with the theme and costumes. Thus, for example, the Futurist Night of 1915 featured a “Futurist Orchestra,” which reportedly “sounded like something never heard before by the human ear.” As the affair moved into larger and larger halls, the decorations grew more and more spectacular, and preparing one’s costume became a task that took months, and required diligent research.

Early balls generally featured a scantily clad butterfly girl jumping out of a coffin or a cocoon. But by the early 1920s, in fact, it was the costumes of the guests, not butterfly girl or the musical entertainment, that were the principal attraction of the Kokoon Ball. The costumes provided a sort of popular lesson in modernism. Designing one’s costume was a serious matter as was generally stressed in a statement that was sent out with the invitation. The one sent out in 1925 read as follows:

The interest you manifest in designing your costume — its originality, attractiveness, appropriateness — materially assists to keep this occasion, year after year, Cleveland’s most splendid Ball. The Club is prepared to assist you by furnishing costume sketches and suggestions, at the Club Rooms, gratis…. Civilian clothes, uniforms, dominoes, tramps, college gowns, ordinary clown costumes and the like will not be permitted. The decision of the costume Committee at the door, in what is considered an appropriate costume, is final.

In addition to screening the guests, the Costume Committee awarded prizes for the most exceptional outfits. In some years this was a cloth “recognition badge,” in others a plaster of Paris medallion, cast in a design befitting the annual theme. The lucky winners were also invited to a private costume party for members only later that year.

The guests did not disappoint, as is apparent from a newspaper account of the ball held at the Hotel Cleveland in 1919:

“From 9 p. m. on-and-on-and on, the regular guests of the hotel, and the bellboys and the maids and the elevator men, and everyone else, hung about the corridors goggle-eyed with curiosity, to catch occasional glimpses of the wild weird creatures who kept coming through the lobby and up the broad stairs to the ballroom, a strange troupe of revelers dressed in the fashion of all the known tribes of earth, and some believed to exist only on Mars, if at all. The costumes were so unusual, so startling and original, that I’m convinced many of the guests at the ball had been planning them for a year, ever since the last Kokoon ball, in fact.”

Each year Cleveland newspapers published lists of the most remarkable costumes. At the 1922 ball there was a Cubist King Tut, a totem pole, Ali Baba and the forty thieves, an office building, a plug hat, and a hot water bottle. At the 1925 ball there was Potiphar’s wife, a Roman Senator, and a man dressed only in a rug. Descriptions of the Futurist Night of 1915 are particularly thought provoking. It included costumes representing such themes as “Happiness,” “A Rhythmic Sensation,” “Storm on Mount Ararat,” “The Feast of Bacchus,” “My Harem,” and “Palpitations.” A recurrent theme in newspaper accounts is the brilliance of color, which became even more intense in after 1916 — when the famed Ballets Russes came to town, with gorgeous modern costumes designed by Leon Bakst, and quickly inspired a host of Cleveland imitations.

A few costumes still survive, in the Special Collections of the Kent State University Libraries, at the Western Reserve Historical Society, and among descendents of Kokoon Klub members. But the principal artistic remnants of the Kokoon Klub today are the posters, tickets, and envelopes designed by members.

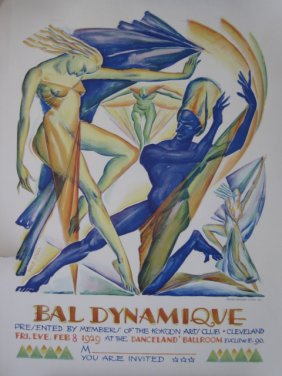

Posters for the Ball

By the twenties the club held an annual poster contest for the Bal Masque invitation. The posters were folded and mailed out as invitations: the best design was awarded a prize of $200. On four occasions the Klub also created souvenir booklets for the ball, which were lavishly illustrated in distinctive Kokoon Klub style, both with illustrations and with advertisements from local sponsors.

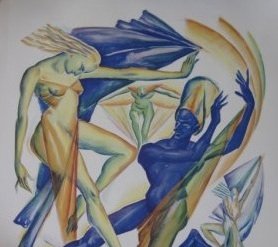

Some of the Kokoon Ball posters stand as among the most remarkable works of art ever created in Cleveland. Often featuring dancers, most of them are Art Deco in style; their iconography is distinctive and peculiar, and often contains abstruse and exotic references. A red-headed figure of Agni, the Indian god of fire, descends from the sky with his consort, “The Spirit of Carnival,” to attend the Kokoon Klub Ball; Midas touches dancing couples with his wand, turning them into gold; a lady with butterfly wings and a caterpillar head manipulates dancers on strings. Sometimes it’s not quite clear what’s going on, as with a lady with a surgical mask and scary claw-like fingers, who manipulates marionette dancers with her left hand. The air of inscrutable mystery is only heightened by the accompanying poem by Hart Crane:

A thousand light shrugs balance us

Through snarling hails of melody;

White shadows slip across the floor

Splayed like cards from a loose hand.

Rhythmic ellipses lead into canters

Until somewhere a roster banters

And midnight carnival swings into dawn.

The designs that won second or third prize in the poster competition were used for tickets or to adorn the envelope in which the poster was sent. One of the most delightful tickets, by Ray Parmelee, shows a female dancer snuggling up to a wise old owl and whispering into his ear. The year before, for the only time in its history, the ball had been cancelled by the Mayor because it was getting too wild. Parmellee’s design, titled “A Word to the Wise,” was surely a humorous admonishment to be discreet about what one witnessed at the ball and to keep it private.

It’s striking that the artists who produced these remarkable designs and decorations are largely unknown today. The first phase of the Kokoon Klub, when it was essentially an offshoot of the Secessionists group, included several artists who are still remembered, including William Zorach, Hugo Robus, and William Sommer, as well as figures who regularly show up in studies of art in Cleveland, such as Abe Warshawsky and Henry Keller. The decorations and posters for the Ball, on the other hand, were quickly taken up by a younger group of artists — the principal figures were Joseph Jicha, Michael DeSantis, Joseph Garramone, Rolf Stoll, Edwin Sommer (the eldest son of William), Ray Parmelee, August Biehle, and James Harley Minter — who today are all virtually unknown. With the exceptions of Biehle and Stoll, none of these figures even merits a mention in the most comprehensive study yet made of Cleveland Art, Transformations in Cleveland Art, published in 1996 by the Cleveland Museum of Art. In the case of Minter, his Kokoon Klub poster is at this point his only known work, and only two facts are known about his life: that he was born in Oklahoma City in 1905 and that he became a member of the Kokoon Klub in 1930. He probably left Cleveland shortly afterward, but we don’t know where he went, what he did, or when he died.

As group, these were young men — they were mostly in their early twenties — who labored 364 days a year on commercial art, producing work under tight creative constraints. But once a year the lid came off and, able to express themselves without restraint, they went wild. They brought a quality of youth and exuberance to their work, which has a vibrant resonance even today.

Once in a Blue Moon

For about fifteen years the Kokoon Klub Ball focused the minds of everyone in Cleveland on modern art. Much of what was on display was silly but that was part of its appeal.

What’s startling is how quickly, in the space of a year or two, the Kokoon Klub Ball went from this peak of popularity to virtual collapse. The precipitating factor, of course, was the Great Depression. In the months following Black Friday in 1929, American industrial stocks lost 80% of their value; 10,000 banks failed; farm prices fell 53%; international trade fell by two thirds; 13 million workers lost their jobs; hundreds of thousands became homeless. Cleveland was particularly hard hit. For example, the Van Sweringen brothers, who built the Terminal Tower, still the centerpiece of Cleveland’s downtown, saw their net worth drop in the space of a year from three billion to three thousand dollars.

In this new climate, the gaiety and blazing color of the Kokoon Klub Ball was out of sync with the world at large. In 1930 the ball seems to have been a hit, but in 1931 it was so poorly attended that it lost money.

In 1933 the Ball was much diminished in size. Rather than renting a hall, the affair was held in the Kokoon Klubhouse; the guest list was limited to 100 couples, and the ticket price was cut from $10 to $5. The poster that year, by an unknown designer, was very blue. It featured two inverted falling female figures against a black background with blue stars and the slogan: “Once in a Blue Moon.” The sexual energy of the event had evaporated. For 1936 there was no ball at all

There was one last serious attempt at a comeback, the ball of 1938, held in the Carter Hotel, which featured a new gimmick: the use of black light to illuminate objects painted with fluorescent paint, leaving everything else in the dark. The star of the evening was a New York showgirl, Leeanova Scotti, dressed in the requisite pair of butterfly wings and nothing else. Unfortunately, the black light illuminated only her wings; the rest was hidden in darkness. The effect was a bit anticlimactic. Indeed, a member of Cleveland vice squad, Charles P. Johnson, the city dance hall inspector, was overheard complaining, “It isn’t like the old days.” Not only were numbers down but the nature of the crowd had changed: the artists and partygoers who in the ‘teeens and ‘twenties had been rambunctious, wild young stallions were now aging geezers, looking back nostalgically to the flaming emotions of their youth.

Allegedly there was one final Kokoon Ball in 1946, just after the end of World War II, but it was an even more muted affair, without a poster or notable decorations. By this time many of the more creative members of the Kokoon Klub had left town; those that remained had aged. Due to changing technology, the sort of skilled lithographer who formed the core of the original Kokoon Klub had gone the way of the dodo and the great auk. What’s more, most of the central purposes of the Klub had been taken over by other ventures. Life drawing classes were available in many other places, and were easily accessible now that almost everyone had a car. The Museum of Art did a better job of putting on art exhibitions, and its annual May Show largely supplanted the annual member’s exhibitions at the Kokoon. Even the art world was changing. As Abstract Expressionism swept the American art world, the once-radical Kokooners discovered that they were now the rear-guard rather than the avant-garde. Increasingly, the crumbling clubhouse became a place for a few lonely old men to gather and reminisce. In 1956, down to twenty-five members, the Klub disbanded.

In truth, by 1930, the Kokoon Klub had already accomplished what it set out to do. In the opening years of the Klub, skeptical Clevelanders looked at modern art with suspicion. But through the Kokoon Klub Ball, the public became a participant in the process of modernism: indeed, the audience itself had become the spectacle.

The Kokoon Klub Ball was a classic example of the “carnivalesque,” a concept first explored in depth by the Russian scholar Mikhail Bakhtin in his 1965 book Rabelais and His World. Essentially, the carnivalesque is a ritual performance, generally performed at specific festivals, when it becomes acceptable to break from everyday experience and challenge social norms. During these moments of carnival, the hierarchies, privileges, norms, and prohibitions of official culture are overturned. But its character is humorous rather than violently destructive. What’s more, the sensual and the sexual are allowed to come to the fore, and challenge our usual inhibitions.

In the case of the Kokoon Klub this carnival was exceptionally dynamic, and associated with a profound process of social, artistic, and cultural change. When the Kokoon Klub was formed everything about Cleveland art was inhibited and grim and grey and out-of date. By the end of the Kokoon Klub the bold design and colors of modern art had become the norm, artistic freedom was celebrated, and even social and sexual mores had loosened and become more flexible and forgiving.

The Kokoon Klub itself was ethnically diverse in a fashion quite unlike any club that had existed in Cleveland before. As it grew, it included recent immigrants from Hungary, Bohemia, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, England, and Russia. It mixed together Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. While a few members were wealthy and well-connected, many of its members came from working-class backgrounds. In short, the Kokooners were broad-minded — ready to accept people for what they were rather than to pigeonhole them with labels and social categories — and the ball was a kind of carnivalesque dramatization of this outlook. In its wild mix of colors, artistic styles and cultural and ethnic types, in its utter disregard of conventional sexual and social restraints, it set the stage for an American society that would be more tolerant and more diverse.

While it never took itself too seriously, in its remarkable posters and decorations for the ball the Kokoon Klub established new pathways for American artists to explore. In some sense, indeed, the Kokoon set the stage for the masterpiece of Cleveland art, Viktor Schreckengost’s jazzy, Cubist-inspired Jazz Bowl of 1930, often considered the greatest achievement of American Art Deco. Like the Kokoon Klub Ball, the Jazz Bowl upended the conventional way of viewing things and brought a lively, irreverent spirit into the stuffy world of academies and art museums. Surely such an achievement would not have been possible without the revolution engineered by the Kokoon Klub, which opened the city up to a new diversity of outlook — not just in art, but in other spheres of life as well. So often the story of art is of things that were made to speak to future generations and which have no interest to us today. The story of the Kokoon Klub is the opposite case: the story of things that were made to be ephemeral, to adorn a single night, and that turned out to have enduring value.

Excerpted text and illustrations from Out of the Kokoon, by Henry Adams, with Lawrence Waldman.

Support paywall free, independent Rust Belt journalism — and become part of a growing community — by becoming a member of Belt.