By Douglas Max Utter

The far edge of Cleveland’s Tremont district drops off abruptly, affording a sudden wide-angle view of industry and commerce in the valley below. A traffic circle at that spot swirls cars onto Interstate 71, or alternatively shunts them down Quigley Road toward the big-box stores at Steelyard Commons, against a backdrop of intertwining highway pylons and bridges. To the west, buildings and properties owned by the global steel and mining company ArcelorMittal spread along the banks of the Cuyahoga, and everywhere exploitation, consumption, and profit commingle in amoral layers. Bearing the deep imprint of human ambition and need, the area is like an economic Olduvai Gorge–or maybe a slope in Purgatory, arguably minus the spiritual learning curve.

Such terrain can also be mined and exploited by the imagination. For a long time, starting when he was a young man and continuing for more than for 40 years, Cleveland artist Randall Tiedman painted tensely expressive, tactile visions most often focused on the human body. But sometime in 2004, he took a step back and began to render an oddly wider world–a sort of stage where he performed intricate melodies of desire and absence and damage. During the last years of his life, his method was to salvage peripheral impressions of industrial views, restored from the margins of perception to form the breaking lines of gray and umber mindscapes. These vistas don’t seem invented, but in some sense read as recovered, or revealed.

Tiedman’s large (typically about 4’ by 3’) acrylic paintings from this time present fraught re-visions of contemporary wastelands, glimpsed from above in a sulfurous near-darkness. They are the stuff of epic poetry, reminiscent of the Inferno and Paradise Lost, an account of the wreckage that attends great sin. If you squint across the aforementioned Industrial Valley (really its name, according to Google) at dusk, you glimpse the sort of end-times panorama that Tiedman improvises in paintings like his nocturnal “Promethean Web” series, or the inhuman honeycomb of tunnels and dams half exposed by a rush of primordial waters flowing slantwise down the picture plane in “Satan’s Chair” (2011).

Familiarity may have numbed most of us to the aesthetic shock of the actual sights visible beyond the guardrails on the daily commute. But underwritten by a century or more of environmental degradation, the scale and corrosive grandeur of the mess in and around America’s cities surely does suggest a once and future kingdom of titanic, chthonic powers – especially if you gaze by moonlight, or by the glare of sodium-compression streetlights, as Tiedman seems to do. Bearing titles with classical or biblical resonance, like the “Limbus Patrum” and “Promethean Web” series, these paintings evoke a psychological reality correlative to everyday experience, emptied of people but filled with surmise. They seem observed not from any modern roadway but–despite their references to up-to-date looking stadiums and specifically industrial structures like water treatment facilities–tremblingly, as if at the reins of a chariot. This is our world seen through the eyes of angel, or demon.

It’s no wonder these vertiginous works have earned Tiedman an enthusiastic new audience over the past half decade. His earlier styles (his first paintings date from the late 1960s) applied some of the same qualities to renderings of the human figure, often distinguished by bravura brushwork and beautiful drawing. But these newer hallucinatory hills, doom-colored tarns–and the hurricane-like devastation swirling around them–convey a very different immediacy and conviction. Perhaps they strike iPad-weary eyes as nearly classical, while retaining a cinematic sweep that feels freshly scripted, as if urgently dictated by subconscious impulses. Tiedman explores as he prophesies, digging among the roots of fascination, evoking the seductions of disaster, distance, and power. It’s exciting to contemporary curators and collectors that he uses such leitmotifs to introduce a highly unusual romantic-apocalyptic slant to the repertoire of regionalism; clearly this is a far cry from your grandparents’ painted midwestern reveries.

Tiedman’s new fans include national art magazines, as well as major museums and collections. Twice featured in New American Painting, he was also collected shortly before his death by the Albright Knox Museum in Buffalo, the Butler Museum of American Art in Youngstown, the Erie (Pa.) Art Museum, and several corporate collections, most notably Progressive Insurance. At the far end of a career marked by solitary, almost monkish activity, those events were practically a firestorm.

Barely within Cleveland’s city limits, a few miles out from downtown in North Collinwood, Randall Tiedman lived most of his life in an up-down style duplex purchased by his grandparents in the early years of the last century. His older brother Richard (who writes commentary and criticism about classical music) occupied the downstairs suite. Grovewood Avenue, which is part of one of the east side’s main bus routes, bumps along a few feet past a narrow strip of front yard, and the neighbors’ houses squeeze in from adjoining lots. About a block to the west, a grassy athletic field spreads across a dozen acres and a small abandoned community pool yawns nearby, dating from the 1960s, seeming like a city planner’s meditation on absence and changing times.

- “Requiem”

Earlier than that, around the mid-century mark, Cleveland’s most popular amusement park, Euclid Beach, was located less than a mile away on Lakeshore Boulevard. In its day, it attracted countless thousands of visitors who filed past the still-standing, turreted gate house. Though the roller coaster and the beach itself are long gone, the location seems to have stubbornly good karma; a well-appointed new Collinwood Recreation Center recently opened on the other side of the road, at one end of an otherwise decaying shopping complex. Whether the zeitgeist is coming or going, the restless shifting of priorities and populations continues, channeled through the hard decades.

All of this found its way into Tiedman’s never-lands, though it’s hard to say just how. He improvised without preliminary sketches or photo references in a tiny back bedroom studio, hunkered in front of oversized etching-weight sheets of paper, grafting hypostatic spiritual scenery from back brain to painted surface as if by sorcery or prayer. Fragments of the fences and batting cages, benches and bleachers on Grovewood show up in the pictures, but so does everything else; Tiedman found grist in every corner of his reality. A short walk from his house to a bridge over the CSX railyards reveals enough industrial-strength creative DNA to power a whole fleet of his “Promethean Web” paintings. Along the way, the road seems pregnant with a life of its own, finally buckling and splitting apart at the corner of a short street named “Darwin.” From this point, you can peer through a fence and see the lumbering freight cars. Punctuated by a gothic-looking grain elevator to the north and the white vanes of a wind turbine to the south, intertwining tracks flex like exposed back muscles, pushing the residential zones of North Collinwood away from the derelict GM and GE factories to the south.

And if, like Tiedman in his paintings, you levitate above this scene and withdraw to a greater height, it becomes clear that the most important view by far, from Collinwood or anywhere else in northern Ohio, is Lake Erie, which shears off all other geographic features and human doings like a titantic guillotine. You may forget the gray waters are there, yet no more than five blocks from the Grovewood house, they loom almost secretly, out of all proportion to daily life, as improbable as Leviathan. Mostly hidden from view either by buildings or the lay of the land, the lake is the priceless dreamtime of the city, cradling actual and imaginary worlds in the same primordial gesture, never to be landlocked or subdivided. Its presence in Tiedman’s paintings is perhaps the crucial way in which he tells the secret truth of place, a secret which his images so compellingly argue. We realize that the fundament of Tiedman’s tragically peaking and crashing visions isn’t earth at all, but water. Paintings like “St. Neot’s Margin” (2008) or “Night’s Speechless Carnival” (2010) have sometimes been tagged post-apocaylptic, but a close look hints at sources in the Book of Genesis rather than the Book of Revelation. These are places half-drowned and overturned by a great flood.

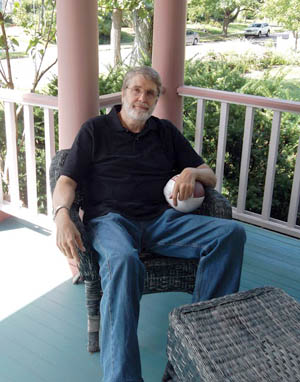

Amid all the drama of his technique, maybe it’s necessary to remember that the sense of place native to Tiedman’s paintings isn’t really on any map but is a residue of the life experience and physical presence of Tiedman himself, who in his early 60s was a slightly stooped but still imposingly tall figure. Despite the neutralizing effects of age and a neatly trimmed gray beard, he retained the ageless intensity of a natural athlete. One of the qualities that unites his different styles and subjects across the decades is the sense of sheer human physicality that they convey. It makes sense that among the complex roots of Tiedman’s self-taught practice, Abstract Expressionism stands out as a central inspiration–a school of painting much inflected by existentialist thought, emphasizing above all gesture and presence and the native spontaneity of truth- telling. Of all the loosely knit groups that invented postwar modernity, the New York based abstract expressionists were the most triumphantly individualistic, and athletic in that they competed in life-long agons not only with each other, but most of all with themselves.

Tiedman was cut from that cloth.

He began to draw and paint when he was teenager, interests strengthened by visits to the Cleveland Museum of Art and by his friendship at that time with Gary Dumm, the future cartoonist of American Splendor fame. He would continue to draw through thick and thin, gradually achieving an artistic identity. He drew soldiers and their girlfriends when he was drafted, and made collages when he came close to dying, not in a fire fight but in boot camp during a deadly outbreak of spinal meningitis. Following eleven months of service in Danang, news of his mother’s death arrived and the army sent him home. A series of jobs followed, including one with Dumm at Kaye’s Books in downtown Cleveland. Eventually he settled into a job as clerk at the Cleveland Public Library, preparing books and materials for the blind. That turned out to be a position he would hold for 32 years.

*****

- Randall Tiedman

So far this is a straightforward narrative. But there’s another interesting twist. Tiedman described himself as a very nervous young man–yet despite that, or maybe partly because of it, he had a longstanding passion for boxing. Intermittently throughout this early period the 6’2,” 185 lb artist not only drew, but jogged and sparred and handled himself very well in the boxing ring.

Tiedman trained at the Old Angle Gym in Collinwood with Sammy Greggs, who had prepared heavyweight hopeful Ted Gullick (eventually defeated by George Foreman) for the ring just a couple of years earlier. Greggs thought Tiedman would have world-class potential by going down a class in weight. Tiedman sparred at the Angle with Windmill White;, he even boxed in Vietnam. Eventually his ambitions faded, but not before he met and talked to legends like Floyd Paterson, Joe Frasier, and Muhammad Ali. He actually saw Ali three times, the last time at his bout with Frasier at the Cleveland Arena.

There’s no telling how important these early boxing experiences are to an understanding of any of Tiedman’s paintings; perhaps they’re not important. Painters don’t have to spend time in the ring (though as Tiedman once reminded me, Picasso was fond of boxing) to master the kind of sparring with line and plane, color and substance that he does so well, or to convey the half-sick feeling that life’s savor, its delight and detail, is kneaded with dull blows, mixed with pain and sweat.

But there’s something about a brightly lit stage, bound around with ropes in a dark room, and the shouting and the smoke and the bell, the intimacy and the distance. This was boxing in its glory days, brutal and shady, but also archetypal, and sexy–a kind of theater that harked back to the ancient origins of drama in sacred rites of passage. During those years, Frank Sinatra might show up ringside as Life magazine’s photo correspondent, and Burt Lancaster pitch in as announcer. Everybody in America knew the names of the fighters. They were more than heroes, they were people who embodied an American dream that has since passed from cultural currency. They were men who devoted their lives to an impossibly punishing discipline, all for the long moment in the bright light. Even when they lost it was like waking up, and what they woke up to was themselves – plus maybe a pile of money and global fame (so it was partly the same old dream after all).

Tiedman’s dark slopes combine a sense of limitless space with an intimate range of painterly techniques, engaging something like the mind’s sense of touch even as they encourage the gaze to sweep to the far edge of forbidding prospects. Maybe that’s the connection with the nighttime world of blood and cigar smoke and the hard side of life on Cleveland’s margins.

Tiedman brings the realities of pain and disciplined brutality to his images, illuminated intermittently as implacable forces rush and twist half-seen in deep shadow.

Maybe time in the ring is something like time in a painting–a matter of accumulation and compression. Under such pressure, pain becomes a desperate way of counting. Minutes stretch between the eyes around the ring, and snap back to the gleam of muscle. Everything evaporates, effort and learning and hope, flattened on the hard surface of plain need. The view in the ring has no real height or depth but is a seed of night, a point that divides before and after, fear and bravery, triumph and defeat. Each of Tiedman’s paintings is, in its way, a bout between paint and thought, angling from the tight closeness of struggle, to the freedom of loss, of falling.

*****

“Inscape in Green and Gold,” “Monument,” “Genius Loci,” are works that speak of hopeless desire and desertion, of long pain and longer hope. They don’t merely propose a prospect or point of view, a country or a state of mind, but seem to incarnate all of these things, as well as a sharp, wounded jouissance. This painterly orgasmic quality parallels the transgressive delight of the alchemist or the tired magician, whose spells and passes, experiments and toil have at last produced a thing whose worth lies beyond mere cause and effect, beyond the last horizon of talent or proficiency. You can get lost in Tiedman’s fields and hills as if they were real places, poking through ruins that might be either the rusting hulks of alien starships, or the blasted roofs and ramparts of Satanic mills.

They came in a flood, these late landscapes. Every week saw a new painting, a new angle, a different hour of the dark night that he visited with his palette knife, or the wan days that dawned over strange derricks and towers, along cold, hostile horizons.

By 2004, around the time that he retired from his job at the Cleveland Public Library, Tiedman became aware that he was sick. His heart raced unpredictably, even sometimes when he was sitting still, skipping beats in an irregular pattern. The sensation was of a rapid, out-of-control fluttering as the electrical signals governing the heartbeat dissipated in a series of jerks across the muscle. Atrial fibrillation rarely results in death, though it generally indicates a serious underlying condition. In Tiedman’s case, this was first of all a much-enlarged heart, and his doctors at the Cleveland Clinic implanted a pacemaker to address the graver dangers, especially the risk of stroke. The operation was a success for a year or two, but then the arrhythmia began to recur, causing symptoms of increasing severity–shortness of breath, weakness, near exhaustion, pronounced nervousness. By 2009 Tiedman’s cardiologists put him on the list for a future heart transplant.

But while symptoms and trips to the hospital continued to multiply at their own uneven pace, Tiedman painted constantly and corresponded with museums and galleries, displayed works in more than a dozen shows, and in 2008 married his coworker at CPL, Susan Wiltshire Kleme. It was in many ways a triumphal period for the artist despite his gradually worsening physical condition. Landscape paintings continued to flow from his hand at new peaks of fluency and excitement. Each seemed to penetrate deeper into the terra incognita of perceptual recollection and invention where Tiedman travelled night after night, hunched in the brightly lit back bedroom. Every time he stretched a new piece of Arches on the easel and picked up his brushes and knives, the flight continued above the black wreck of worlds, the rich mosaic of slanting, abandoned ochre fields. Rivers twisted into far hills at the edge of vision, moonlit, starlit, wreathed in mist and the chill winds of a country that was everywhere and nowhere, that was mapped in his breast, that was the steady ground beneath his fluttering, high-flying heart.

Douglas Max Utter is a painter and art critic, and the recipient of a 2013 Cleveland Arts Prize.

Stunning. Thank you Doug. Thank you Randall.

Gorgeously written review-essay-tribute. I was bowled over by Tiedman’s industrial paintings when I saw them.

Great essay. I got a chance to see some of these at the Kokoon Gallery at the 78th Street Studios last summer, and the artwork was awesome.