It was a Saturday evening in the summer of 1974 when Duane Abbajay realized his American Dream was devolving into an American Nightmare.

By Dominic Vaiana

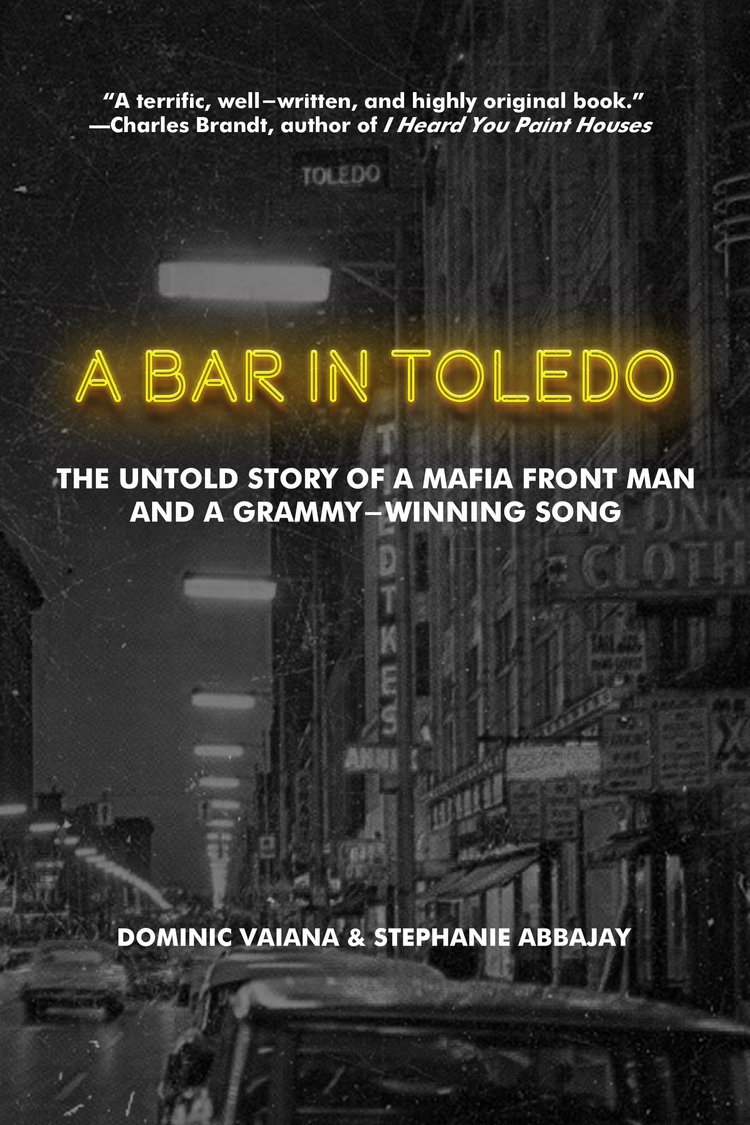

The following is an excerpt from A Bar in Toledo: The Untold Story of a Mafia Front Man and a Grammy-Winning Song by Dominic Vaiana and Stephanie Abbajay (University of Toledo Press, 2022). It has been edited slightly for clarity and context.

It was a Saturday evening in the summer of 1974 when Duane Abbajay realized his American Dream was devolving into an American Nightmare. The crowd at his nightclub was small and lifeless, so he tossed back the rest of a vodka-grapefruit and headed home early. He sat behind the wheel of his maroon Buick LeSabre, staring ahead as the skyline of downtown Toledo, Ohio, disappeared in his rearview mirror. A Vantage cigarette burned in the ashtray. A Detroit Tigers game played on the radio. A bag of See’s Candies was open on the console. Cigarettes, baseball, and candy: lifelong pleasures, but none was a comfort to him on this night.

On the passenger seat next to him were fragmented notes scribbled with reminders to himself about his golf game: Head down. Swing THROUGH. Mixed in with these missives were slips of paper with the names, dates, phone numbers, and the amount of money he owed to people he was warned about.

How, he thought, am I going to get out of this one? How did I get into it in the first place?

Duane knew this drive up Interstate 75 to I-475 all too well. He had spent the past twelve years operating The Peppermint Club, a wildly successful nightspot that brought the hottest musical acts of the 1960s—Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Frankie Valli—to America’s Rust Belt. He was a beloved local celebrity who had carved out a reputation as a rock and roll impresario, a gentleman, and a savvy businessman. And that wasn’t a matter of luck. The club was open 365 days a year, which meant Duane showed up to work every night—Christmas, Easter, and Thanksgiving included—from 7:00 p.m. until 3:00 a.m.

The son of Syrian immigrants, Duane was driven by the raw ambition that surged through the veins of so many first-generation Americans of his time—always striving for success, always working, always hustling, constantly on the lookout for his next big break or a quick buck. You didn’t have to be Nelson Rockefeller to understand how the system worked: start at the bottom, work your ass off, fight your way to fame and fortune, don’t look back.

Duane was a product of the Great Depression and post-war America. Born in 1933, he was the second youngest of sixteen children, so naturally he craved autonomy, acceptance, independence, and, most of all, money. He wanted to make it—not by taking orders from some square in a suit, but through his own wit and grit.

From the outside, it appeared that Duane had accomplished all of that and more with the nightclub he had poured his heart and soul into for the majority of his adult life. He was the poster boy for the American Dream: a self-made man with a staunch work ethic, a stunning wife, four kids, a beautiful home, and, most importantly, respect.

But it was all slipping through his fingers.

At 41 years old, Duane’s hairline was receding, his olive skin had started to wrinkle, and his mind was riddled with anxiety. The wad of cash he always kept in his front pocket was still thick, but it was now layered with fives instead of fifties. The liquor board was threatening to take his license. Downtown Toledo was losing its luster as residents and businesses flocked to the suburbs. Stores shuttered one by one, and the once-busy streets drained of life.

Duane’s wife was threatening to leave him and take the kids with her—understandably so. He owed money to a litany of racketeers, loan sharks, and other shady characters. Every time someone knocked on the door, she expected FBI agents, mobsters, or another woman. Neighbors, relatives, in-laws, and church gossips all doubted Duane’s club would survive through the summer. Doo-wop was dead and rock and roll was giving way to disco. The artists that once prompted patrons to line up around the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Ontario Street could barely fill a room.

Losing money is one thing, but falling short of your own expectations and the ones your family and community have for you— telling your daughter “no” when she wants a new bike, going back to punching time cards at a nine-to-five job—those things will make a man desperate.

The stress and anxiety came to a crescendo as Duane pulled into his driveway on leafy Douglas Road. He wasn’t a drinker, but that evening he had had a couple, to the surprise of his employees. He hated booze, but he needed it that night. The buzz from his vodka-grapefruits hit him as he swiveled his sore hips and hoisted himself out of the Buick. As usual, he entered the now-quiet house through the mud room, took off his shoes, slid the glass door open, walked through the darkened kitchen, and took off his burgundy polyester pants, draping them neatly over a dining room chair. Then he did what any other troubled man would do: grabbed some leftovers from the fridge, sprawled on the couch, and turned on the television to numb his pain.

It was here, glowing inside a faux walnut console TV, where Duane found the insight that would salvage his American Dream and take his bar from the brink of failure to immortal fame. His ears perked up to the sound of banjo music and his eyes widened at the sight of a cartoon donkey. On TV was a rerun of Hee Haw: the hillbilly-inspired variety show that blended corn-pone humor with A-list country music talent.

Suddenly, Duane was ready to make the biggest gamble of his life.

***

That same year, Kenny Rogers called his manager and told him he was ready to quit the music business.

“I can’t take it,” said Rogers. “It’s got me depressed.”

Rogers had just left his rock band, Kenny Rogers and the First Edition, after a decade of success in which they cut several Top 40 hits. Up until the breakup, Rogers had the sex appeal of a quintessential rock star: long hair, a thick beard, and a twinkle in his eye. Young women, dazzled by his rugged looks and silky-smooth voice, threw their panties on stage at his concerts. Now, Rogers was living a shell of his former life. He was saddled with debt and resorted to hawking guitar lessons for quick cash. Having grown up in Houston housing projects, Rogers knew what it felt like to be poor—and he feared his life was trending back that way.

After reflecting, Rogers decided to continue his music journey, but this time he would go at it as a solo artist. In the fall of 1976, he headed to the city where music careers were born and bred: Nashville.

As Rogers attempted to navigate the local music scene, a country music producer for United Artists Records named Larry Butler received a phone call from a friend.

“Do you like Kenny Rogers and the First Edition?” the caller asked. “Gosh, yes, I love Kenny Rogers,” said Butler.

Once Butler found out Rogers was living in Nashville, he dialed up his friends at local radio stations.

“I’m considering signing Kenny Rogers,” said Butler. “If I record him country, will you play his records?”

“Larry,” said one radio executive, “Every time he cuts anything that’s halfway country, we play his records.”

Butler’s wheels started turning and he invited Rogers to his office.

Fifteen minutes later, he had signed a deal with United. Rogers, now sporting a salt and pepper beard and singing with a gravelly voice, cut his first country single, “Love Lifted Me.” The record did little more than establish Rogers’ name on country radio stations, and the two singles that followed barely cracked the bottom of the charts. A sense of urgency set in: Rogers was closing in on 40 years old and he had yet to record a true hit.

“We didn’t have that career song,” said Butler. “I looked for it and Kenny looked for it.”

Rogers had enough musical acumen to know what had the potential to be a hit. “If it doesn’t grab you right away, it won’t grab the public right away.” He told Butler if his next record didn’t catch on, he was going back to rock ‘n’ roll. A full year passed without the hit they were chasing, and then Roger Bowling paid a visit to Butler’s office.

Bowling, a rugged-looking songwriter, was riding the success of “Blanket on the Ground,” a number one hit he penned for Billie Jo Spears. Now he had a new song that he co-wrote with fellow tunesmith Hal Bynum. Bowling took out his guitar and played it right there in the office for Butler and Ken Kragen, Rogers’ manager. Kragen looked over to Butler: “This is either the biggest hit or the biggest flop I’ve ever heard.”

***

Two years before that 1976 meeting in Larry Butler’s office, Hal Bynum was caught up in marital troubles. The 41-year-old songwriter was burnt out and skipped town to get some alone time and “do some serious drinking.” On a Friday evening, Bynum boarded a Greyhound bus in Nashville and headed north. The next morning, he woke up with a hangover in Toledo, Ohio.

“I had some time to kill and walked from the bus parking lot across the street to this bar,” he told Hank Harvey in a 1977 Toledo Blade interview.

Thirsty for a beer, he wandered through the padded doors of the Country Palace.

As Bynum sat at a table in the back corner nursing his hangover, he overheard an argument between a spurned husband and his estranged wife. The couple exchanged expletives and insults for several minutes before the man finally had enough. As he stood up to leave, he left the woman with a parting remark: “All I can say is, you picked a fine time to leave me.”

That sentence gave Bynum a moment of clarity—and an idea for a new song. He reached for the paper napkin on his table and started scribbling lyrics inspired by his eavesdropping. When Bynum returned to Nashville, he wrote a version of the song that incorporated a blind guitar player into the story, but he knew it wasn’t right. Bynum didn’t bother to touch the song again until a year later when he began working with Roger Bowling on record albums.

“We’d both had a lot of songs on the charts, and we liked one another’s writing,” said Bynum. “So, we decided to write some things together.”

For their first collaboration, Bynum dug through his papers and pulled out the song he began writing on that booze-soaked morning over a year ago in Toledo, but this time, they put the story back where it really started: in the Country Palace. Bynum and Bowling took creative liberty with the song, which became a first-person narrative about a man striking up a conversation with a disheartened woman named Lucille on the rebound from an unhappy marriage.

In a bar in Toledo

Across from the depot

On a bar stool she took off her ring…

Bowling was sure they’d just penned a hit, so he waltzed into Larry Butler’s office, brimming with confidence. He sat down with his guitar and played “Lucille.” Butler knew this was the song he’d been looking for over the past year, so he called Rogers into the studio to take a listen.

“Larry, I agree with you, that’s a great country song,” said Rogers. “But I think it’s too country for me.”

“Lucille” was, indeed, old timey. It didn’t match Rogers’ persona as the pop-country crossover artist that United wanted him to be. Butler wouldn’t let the opportunity slip, though. He wanted to tell the world: this is the song. “Kenny, I think this is an important song for you to do because it will show your audience you’re serious about country music,” he said. “It will validate you in the market. It will validate you in radio.”

Rogers questioned the original ending of “Lucille,” but after the last verse was re-written he was finally confident the song would do well on the radio. By January 1977, Ken Kragen, Rogers’ manager, was ready to pull the trigger: “Release it.”

Rogers and his accompanying band were playing a small club in Canada shortly after the song debuted. While eating breakfast the morning after their show, Rogers got a phone call from United. “Guys,” he told them, “This ‘Lucille’ thing is really going big.”

Just weeks later, Rogers was invited to play “Lucille” on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. After the show, Larry Butler got a call from Atlanta.

“We just got a reorder for ten thousand copies of that single.”

“What?”

“You heard right—ten thousand. It’s exploding.”

By the summer of 1977, “Lucille” was an international sensation. It reached number one on the Billboard Country Singles chart and number five on the Billboard Hot 100. Rogers swept every major award a solo country artist could win. He took home a Grammy for Best Country Vocal Performance, the Academy of Country Music Song and Single of the Year, and the Country Music Association Single of the Year. Overseas, “Lucille” climbed to number one in Canada, the U.K., Yugoslavia, and South Africa.

As millions of people across the world sang along, they began to wonder: What’s this bar in Toledo Kenny Rogers is singing about?

***

On June 13, 1977—one week after “Lucille” hit the mark for a million records sold—Toledo Blade staff writer Hank Harvey chronicled the song’s history and the shot of life it gave the Country Palace in the article: “Hit Tune Spinoff Of Toledo Remark: Songwriter Composes ‘Lucille’ After Hearing Comment In Downtown Club.”

The accompanying photograph showed Duane holding a copy of the record signed by Rogers. His long sideburns with streaks of silver contrasted with his child-like smile. Jim Roberts, the bartender who served Hal Bynum his beer two years prior, looked on endearingly.

“[‘Lucille’] was the No. 1 in requests for five weeks straight at WTOD radio,” wrote Harvey.

The Blade article created a ripple effect. The Country Palace now saw devout Kenny Rogers fans from all over the world making pilgrimages to 725 Jefferson Avenue to drink and dance at the real “bar in Toledo” that Rogers sang about. Some weekends, out-of-town visitors at the Country Palace outnumbered the locals. Duane wasn’t just running a nightclub now—he was running a tourist attraction.

“Some of ‘em come in and sit down, look around, and say ‘So this is the place,’” Duane told Harvey. “Business is booming.”

Rogers himself made a trip to the Country Palace in the fall of 1978 to immortalize the home of “Lucille” while he was in town to perform at the Sports Arena in east Toledo. His promoters figured out the bar was just across the river and called Duane to set up a photo op for Rogers to leave handprints and footprints in a block of cement that would be displayed inside the club. While the photographers set up their cameras, Duane gave Rogers the grand tour. Duane’s kids—teenagers at the time—followed along like groupies, looking on as Rogers kicked his ostrich skin cowboy boots up on Duane’s desk and made the most interesting small talk you could imagine.

When it came time for the ceremony, Rogers mistakenly stepped into the wet cement with both feet and started to sink down. He tried to step out, but his boots were stuck, and the cement was beginning to dry. Rogers quickly signed his name in the cement, but instead of leaving footprints he left behind his boots—far more valuable than any footprint. Rogers left the Country Palace in his socks.

Duane adopted many American traditions, but ooh-ing and ahh-ing over celebrities wasn’t one of them. Personal visits from Grammy winners, global publicity, having his building listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and even having an iconic song forever tied to his bar meant nothing if he couldn’t turn a profit every month—so that’s all he focused on. When asked what he thought of Hal Bynum, the man who single handedly made the Country Palace a tourist hotspot that put untold sums of cash into his pocket, Duane’s only remark was, “That guy was a drunk.”

Perhaps Duane was the kind of guy who could make you believe he didn’t care as opposed to the kind of guy who truly didn’t care. Surely he craved status and validation. Who doesn’t? Regardless, he had an impressively short memory when it came to show business. He never dwelt on the inevitable highs and lows of the nightclub business. He had a Zen-like focus on the present moment, never letting his ego obstruct the next opportunity.

***

To ask whether Duane Abbajay was successful is a paradox, because Duane Abbajay was two different men, and by the late 70s the contrast was starker than ever before. On one hand, there was Duane the proud suburban dad who sat in the front row at his son’s football games and took his daughters to Shakey’s Pizza. Then there was Duane the philandering club owner who golfed and dined with vicious criminals.

When he was up, laughing with a boyish smile and bright eyes, you couldn’t get close enough to him. When he was down, fighting the anxiety and insecurity that festered deep in his mind, you couldn’t get far enough away.

Both of these people are in him—are him. He was sprinting towards a finish line that didn’t exist, and it would take something substantial, perhaps even traumatic, to bring him down to earth.

***

A Bar in Toledo is available through the following retailers:

Dominic Vaiana is a writer, ghostwriter, and founder of Law 6 Media, a marketing agency for venture-backed brands. He has worked with Spotify, Rémy Cointreau, Intuit, and Mastercard. He lives in St. Louis, Missouri.

Stephanie Abbajay is the co-owner and managing partner of David Stine Furniture. She is also a writer and editor. She has written dozens of articles and essays and has ghostwritten five books. She lives in Dow, Illinois, just outside St. Louis.