By Jonathan Foiles

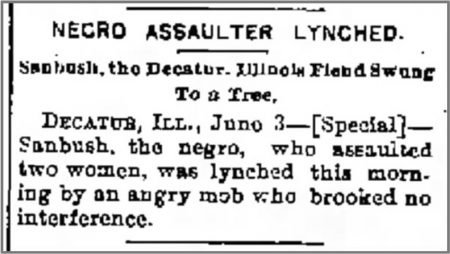

On June 1, 1893, two local white women, a Mrs. Dill and a Mrs. William Vest, had reported that they were raped by an African-American man. Bands of white men roamed through the streets and fields, intending to lynch the perpetrator. Less than 24 hours later, Samuel Bush, 30, from Mississippi, was apprehended by local police.

Bush was an itinerant day laborer who had only been in the area for a few weeks. He admitted that he had stopped by the Vest farm for a drink of water but denied committing any crime. Later he elaborated and said that after Mrs. Vest gave him a drink of water, he asked her for food as well. He said she responded by screaming loudly and, in an effort to calm her, he reached out to grab her arms. According to Bush, she fled, and he quickly fled as well. Bush was identified not by either of the alleged victims but by a third party named Barnett, who was the one that had directed Bush towards the Vest farm in the first place.

That evening a crowd gathered outside the jail where Bush was being held and grew until it numbered 500. Around 2:00 a.m., a group of 100 men armed with shotguns, rifles, revolvers, and knives marched in a column three abreast towards the jail. They wore no masks and made no attempts to hide their identities. Once inside Bush’s cell, three men grabbed the mattress, and Bush tumbled out nude from inside. By this time 1,500 people had gathered outside the jail, some of them lining nearby rooftops to spy on the mob’s progress through the jailhouse windows. Bush was led to a street corner across from the county courthouse. He asked to pray before he died. Kneeling on the brick street, he claimed his innocence and then prayed that he might meet his murderers in heaven someday, and asked God to receive his soul.

Between 1880 and 1940, some 250 African-Americans were lynched in the Midwest.

The crowd indicated that they had had enough. The noose made of halter ropes and hanging from a telegraph pole was placed around Bush’s neck and he was swung into the air. Bush fell to the ground, the wire from which the noose hung not being strong enough. The mob requisitioned a passing hack and made Bush stand atop it. They tied the knot more securely to the post. The hack moved forward and Bush’s body hung. After 15 minutes, he was dead. His body remained above the crowd until 4:00 a.m. when the coroner came to take it down. The noose was cut into pieces and distributed to the crowd as souvenirs.

The lynching of Samuel Bush did not occur in Alabama, Mississippi, or any of the other states typically associated with that particular form of racial terror. Rather, Bush was lynched in Decatur, Illinois.

* * *

Until recently, the data on lynching in the United States was sparse. No one source was very comprehensive, and most of the data focused on the deep South. The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), an organization committed to challenging racial injustice and helping the country come to terms with its history of racial terror, has invested hundreds of hours of research to expand upon the available data. After examining the 12 Southern states with the country’s highest number of lynchings, EJI began to expand their work beyond the South and, earlier this year, released an amended edition of their report, Lynching in America, to include more than 300 lynchings of black people between 1880 and 1940 throughout the Upper South and the Midwest, including Oklahoma (76 lynchings), Missouri (60), Illinois (56), West Virginia (35), Maryland (28), Kansas (19), Indiana (18), and Ohio (15).

Belt Magazine spoke with Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director of EJI, regarding his organization’s research and findings on lynchings in the Midwest, including that of Samuel Bush.

Belt Magazine spoke with Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director of EJI, regarding his organization’s research and findings on lynchings in the Midwest, including that of Samuel Bush.

“The research is very hard because there’s often a lack of documentation,” said Stevenson, explaining that “in some places in the Midwest, there was a greater awareness that lynching was wrong.

“It was easier to find information on lynchings in the Midwest between the 1890s and 1910s,” adds Stevenson, like in the case of Sam Bush, but after that, attitudes began to shift and the “press was not as comfortable providing details…. Conversely, there was a pride in racial violence and terror in the deep South that meant they were more willing to concretize the memory of lynchings.”

For the Midwest, said Stevenson, this lack of institutional memory means that in some key ways the region is more prone to historical amnesia than the South.

When asked how attitudes about race in the Midwest differed from those in the South, Stevenson said, “while the Midwest and the West were not as influenced by the legacy of antebellum slavery, there were parts of the Midwest where support for slavery was very strong.” Some cities and regions were heavily populated by Southern transplants, and they brought their attitudes about race with them. And as more black people migrated north, the instances of white people committing racial violence increased.

When asked what made lynchings in the Midwest different from those in the South, Stevenson said, “the more north and west you got, the more lynchings were in response to accusations of crime, as opposed to social transgressions.” Still, said Stevenson, “lynchings had many of the same features regardless of area.”

Today, Stevenson believes that America needs a truth and reconciliation committee to address the legacy of racial violence. “We need a process like in Germany, South Africa, and Rwanda,” he said, adding that “communities should work to express remorse and admit complicity in tolerating barbaric and torturous violence.”

To that end, EJI has begun construction for a museum and accompanying monument in Montgomery, Alabama, to remember America’s more than 4,000 lynching victims. It is set to open in April 2018. Atop a rise that looks out over the city, hundreds of floating columns bearing the names of the victims of lynchings will hang suspended in the air. The surrounding park will contain duplicate columns for each of the over 800 counties where a lynching took place meant for each county to claim and install as a local memorial, including Macon County, Illinois, where Samuel Bush was lynched in Decatur.

Artist rendering of The Memorial to Peace and Justice, informally known as the National Lynching Memorial, expected to open in 2018.

* * *

It seemed as if justice might be found for Sam Bush shortly following his death. The names of the mob leaders were published widely in the newspapers, and they were well known to the locals. The governor of Illinois offered $200 per arrest and conviction. On June 15, a grand jury began to call witnesses. The Chicago Tribune reported that at least 30 indictments were forthcoming. They were wrong; two weeks later the grand jury declined to offer a single indictment. The judge in charge of the grand jury considered trying again, but local business leaders warned him such an effort would be “inexpedient,” so the judge changed his mind, stating, “I feel that it is an extremely humiliating thing to acknowledge that the law which has been openly violated cannot be enforced at present.” There is no record that any of Bush’s murderers were ever brought to justice.

For the Midwest this lack of institutional memory means that the region is more prone to historical amnesia than the South.

A seven-story building stands on the northeast corner of the intersection of Wood and Water streets where Bush was lynched. The Macon County Courthouse still stands across the street. No memorial marks the spot where Bush died. The Macon County Historical Society has expressed interest in claiming their marker from the Equal Justice Initiative’s museum, and conversations are currently underway as how to best go about it.

“The lynching of Samuel Bush in Decatur, Illinois, was a terrible travesty and a blot on the character of the county’s citizens in 1893,” Mark W. Sorensen, the official historian of Macon County, told Belt Magazine. “Mob action should never be tolerated nor forgotten.”

History has preserved little of Samuel Bush. His body was displayed in a coffin the day after his death, and later buried in a potter’s field. Only intending to stay in Illinois for a few weeks, he left no ties in Macon County. Few know his story.

Hours before his death, Bush dashed off a letter to a cousin in Alabama. It never arrived, but it was printed the next day in some local newspapers.

Dear Louis Collins my cousin:

I am in jail and am into a very bad scrape. Tell Felix and Myron and your other brothers and all of my connections to make up for me the sum of 48 or 50 dollars and send here quick. I believe I can come clear for that or not less than 25. See my father and brother. They is nigh there. Now is the time of need. I never did ask for any favors of you all. Please grant this one at once if you all haft pawn something. Send the money to this Lawyer & he will clear me. If not I expect to be Linched. If you all fail try all of them men & woman to make it up, if nickles & dimes do so. Pray for me, earnist in hart. This said to be white women ‘cuse me of hurting her. Send the money at once.

Louis I write to you when I was at Carrollton & never hered any more. If uncle Bill & my other uncles to help me & once if I am at myself I could tell you all about it. Tell my father to borry the amount of money I sent a year ago if he please & send me some with out fail & no delay. I am, your cousin.

Sam Bush

___

Jonathan Foiles is a writer based in Chicago. He has previously written for Slate and can be reached at [email protected].