There seems to be a complex equation that residents have to live with, a struggle between acknowledging the past and hoping for the future while demonstrating their community’s resilience. A necessity of crafting out a tomorrow in the rust.

By Emiliano Aguilar

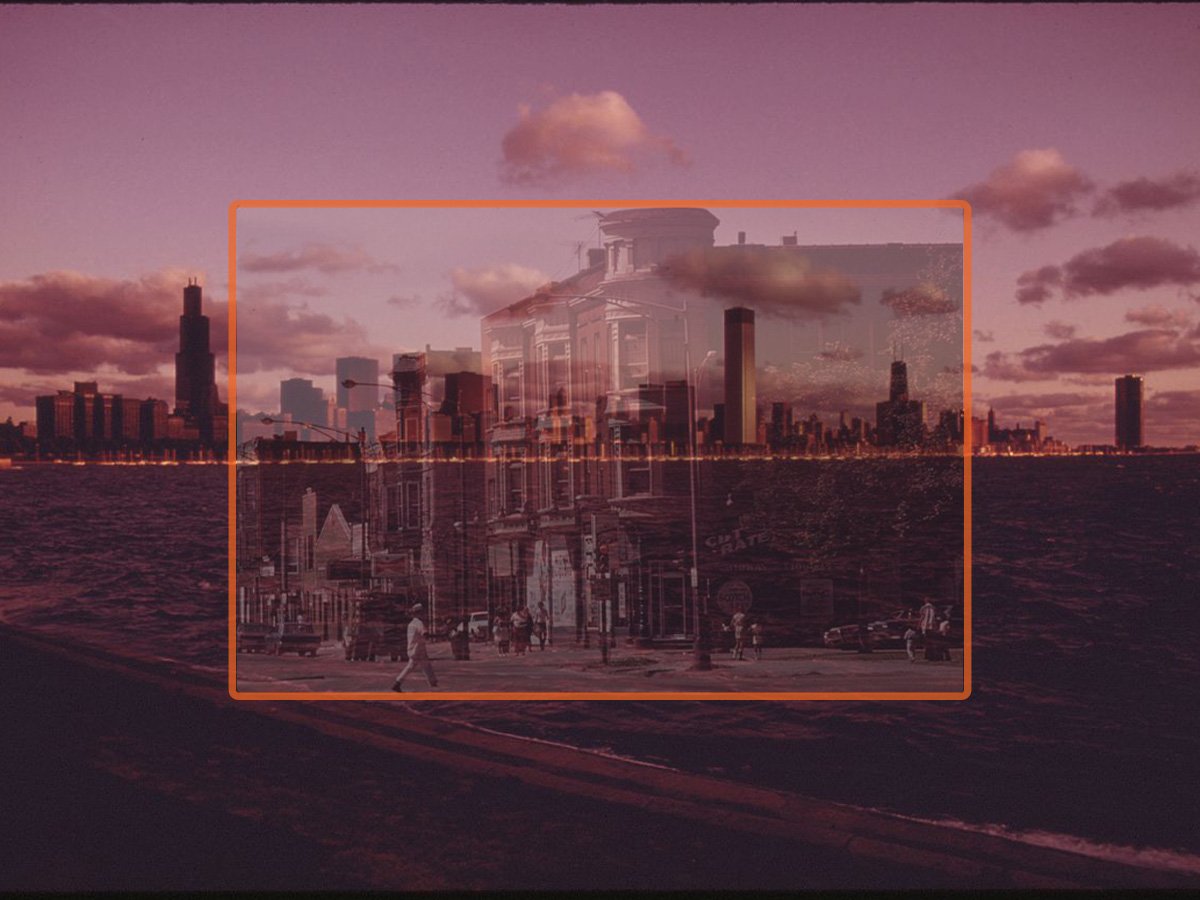

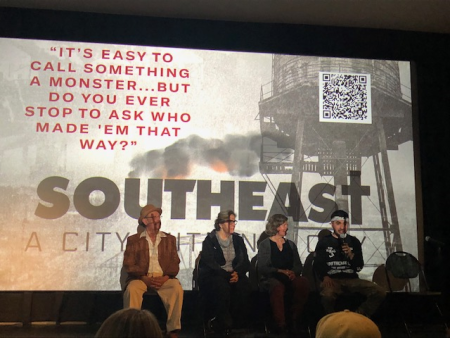

“It’s easy to call something a monster… but do you even stop to ask who made ‘em that way?” A quote that can’t help but grab your attention. Displayed prominently on the poster for director Steven Walsh’s Southeast: A City Within A City at the Montgomery Ward Lecture Hall of Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History entrance, where I attended an early screening. Stage right of the screen sat the cinematographer Matthew Goetz and Roger “Coco” Gomez playing an instrumental song on guitar. Waiting for the film to begin and listening to the light chatter from the growing audience, I was left momentarily with my thoughts.

I heard much about Southeast for nearly two years leading up to this event, from some newspaper coverage to friends and colleagues mentioning this work-in-progress happening just over the state line from my home. The documentary explored the growth of a vibrant community on Chicago’s southeast side, the divestment that plagued the deindustrialization era, and how the residents struggled to live with their world turned upside down. However, what really caught my interest is that the driving force behind the project was a fellow region native, Steven Walsh, who grew up in the Southeast side. After watching the trailer on Facebook, I decided that I had to see how else his personal connection came into understanding a region completely unlike the one he or I grew up in.

Panel discussion after documentary screening. From left to right: Roman Villarreal, Susan Sadlowski Garza, Christine Walley, and director Steven Walsh. Photo courtesy of the author.

As I sat in the theatre seat waiting for the screening to begin, I wondered about a certain tension. So often, we are encouraged to wax nostalgically about neighborhoods that once were. I often hear about this as folks lament the faded glory of my hometown of East Chicago or neighboring cities like Gary and Hammond. And while many interpret deindustrialization as the final chapter for many of these places, they still remain home to thousands of people. While some live in these neighborhoods out of necessity, others choose to remain. And grappling with choosing to stay becomes a struggle itself. There seems to be a complex equation that residents have to live with, a struggle between acknowledging the past and hoping for the future while demonstrating their community’s resilience. A necessity of crafting out a tomorrow in the rust.

The documentary screening was part of an afternoon highlighting the rich culture and history of the Calumet Region, stretching from the Pullman neighborhood towards Michigan City, Indiana. And many of the neighborhoods and cities within this region have attained a negative reputation, as the documentary’s poster alluded to for the Southeast side. Hearing from fellow residents and natives of the region, the evening served as a rare opportunity to tackle the often-overlooked history of the region collectively. Aside from the opening remarks, it all began with Gomez, in the documentary, lamenting that “It didn’t always use to be like this.” The documentary overlapped Gomez’s reminiscing of the Southeast Side of his youth with images of the neighborhood today.

Ironically, the idea for first-time filmmaker and Southeast Side native Steven Walsh’s documentary about his hometown started much the same way – with ambient background sounds. A graduate of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign’s School of Business, Walsh, who had initially planned to work for Google, instead moved to Houston as a part of Teach for America. In 2015, after completing graduate school at John Hopkins, Walsh returned to the Southeast Side of Chicago and began looking for a creative outlet, experimenting with film, originally helping a high school friend on the business end of his production company shooting music videos.

In 2016, when Walsh bought a camera to learn some of the techniques himself, he turned to recording his grandfather, Roger “Coco” Gomez. Walsh recalled that “he used him [Gomez] as a prop to train basic cinematography.” However, when he asked people to comment on the film, everyone was captivated by Gomez’s lyrics which he played from the comfort of his longtime home. Walsh was surprised, recalling the lightbulb moment “I took for granted this genius sitting next to me.” Each of Gomez’s songs, a mix of folk and blues, exposed not only a life of pain and trauma but the optimism of youth and the joy of living among the sprawling steel complexes. Listening with renewed attention, Walsh became captivated by the stories his grandfather told through song as well as those that remained unsung.

From there, he began to ask his grandfather questions with the intent of developing a movie or drama series about the stories. What unfolded became an intimate look into the story of the Southeast Side. In 1952, Gomez and his family left San Antonio, Texas, for Chicago. Originally a cherry picker, Gomez’s father settled in the city, drawn to the pay and livelihood afforded by industrial work. Like so many others, Gomez followed his father into the mill when he got older. He worked at Republic Steel for ten years before the steel mill closed. Like thousands of others in the Calumet Region, Gomez found himself a victim of deindustrialization.

Walsh notes that his grandfather’s story, which is the emotional core of the documentary, is “just a small version of the mega story”. Walsh described the experience as “building a puzzle, not chiseling, not a blank canvas. I was building a puzzle, but it was meeting me halfway.” And his grandfather became an important aide in building that puzzle and filling each gap with another story, or as Walsh prefers, archetype, to complement the mosaic of the Southeast Side. Walsh recalled that at one point, his grandfather called a friend from the area that he hadn’t spoken to in fifty years.

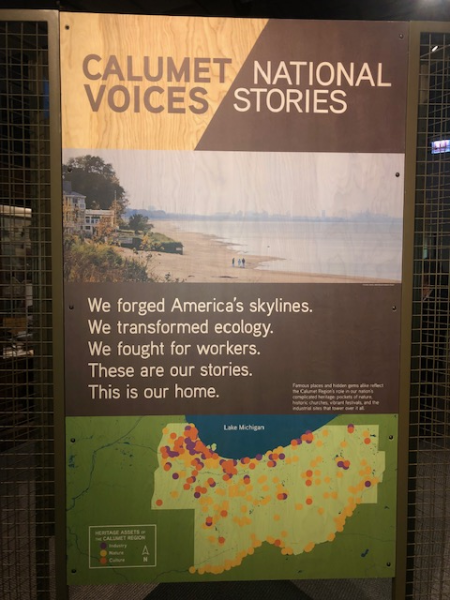

Map of the Calumet Region displayed at the Calumet Voices/National Stories exhibit at the Field Museum. Photo courtesy of author.

As a lifelong native of the bistate Calumet Region, which stretches from the Southeast Side towards LaPorte County, Indiana and includes my hometown of East Chicago, Indiana, so much of the story resonated with me. My grandparents traveled to East Chicago in the 1960s from Nueva Rosita in Coahuila, Mexico, drawn by the promise of the steel industry. For years, my grandfather worked seasonal work in Texas. While his job in Inland Steel allowed him to buy a home in neighboring Hammond and raise my father and his siblings, the promise of the steel industry began to decline in the 1980s. Like Walsh, by the time I was born, there was a disconnect between the community I saw and the one from the stories of my grandparents.

For decades before the mills closed, the Southeast Side captivated the attention of its residents and folks across the region. Situated on the shores of Lake Michigan, the Southeast Side became a hub of industrialization. As longtime curator at the Southeast Chicago Historical Society, Rod Sellers proclaimed, “The story of Chicago’s Southeast Side is the story of steel.” As early as 1875, plans arose to make the Calumet district the world’s steel-producing capital, as industrialists of all sizes planned sprawling steel mills, one in each neighborhood, and smaller mills to scatter throughout the region. For decades, mills like Wisconsin, Acme Steel, US South Works, Republic Steel, and Iroquois (later Youngstown) Steel employed thousands of workers.

However, the heyday of the steel industry began to collapse when Wisconsin Steel closed overnight on March 27, 1980. The event proved a warning of things to come as other mills began an often slow and daunting downsizing. Unable to recover from the closing of the mills and the divestment from their homes, some turned to crime, others to alcohol, and many more died. At one point in the documentary, a small group of former steelworkers, led by Frank Lumpkin, organized a march demanding their pay and pensions years after Wisconsin Steel abruptly closed. The splicing of historical footage of Lumpkin’s protests alongside newspaper coverage about the massive layoffs, proved a jarring emotional experience, especially as the documentary discussed the deaths of former steelworkers in the decades after the mill’s closure.

With each subsequent interview, so many interlocking threads appeared for Walsh to pull. However, for the filmmaker, none appeared as prominent as family and survival. He interviewed his Uncle John, a Vietnam veteran, who recalled the painful times of steel mill closings simply as “Doing what you gotta do to take care of your family.”

At the conclusion of the film, the audience gave Walsh, his grandfather, and their team a standing ovation. After the screening, a panel discussion between Walsh and three of the folks interviewed for the documentary began. These panelists included former Chicago Teachers’ Union Vice-President and 10th Ward Alderwoman Susan Sadlowski Garza, who is the daughter of steelworker and labor leader Ed Sadlowski; Roman Villarreal, a Chicago sculptor, painter, and consultant who mentors artists from his South Chicago space Nine 3 Studios; and Christine Walley, Professor of Anthropology at MIT and author of Exit Zero: Family and Class in Post-Industrial Chicago and a co-creator of its corresponding documentary of the same name.

All three panelists, who are natives of the Southeast Side, discussed the documentary and their neighborhood. While each understood their relationship to the region differently, they all recognized the criteria for change. Walley noted that support for people in the community is a vital necessity in deindustrialized cities. At the same time, Villareal noted that serving as an example is a meaningful way to foster change. Sadlowski Garza credited Villareal’s art programs as one of the many ways residents can take pride in the region’s industrial heritage.

Villareal recalled joining the mill somewhat reluctantly. At seventeen, his father said, “You’re having too much fun on the street,” and had the young man apply to work at the mill. Villareal, who wanted to go to college for art in Chicago, said he worked from 3 PM to 11 PM but still found a creative outlet in the mill. Around work, he found clay and began crafting sculptures, some of his coworkers, others of friends and family. He would then hide these sculptures around the mill “like Easter eggs,” often thinking nothing of it until he later found out how infamous they had made him.

Roman and Maria Villarreal in front of figures inspired by members of the South Chicago community. Similar to the ones Villarreal hid around the mill as a young steelworker. Photo courtesy of the author.

Highlighting the story’s applicability to the broader region, the Field Museum concluded the day’s program with a guided tour of Calumet Voices, National Stories exhibition. The exhibit featured items from the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum, which Walsh incorporated into the documentary, and many other historical societies across the region. Madeleine Tudor, Senior Environmental Social Scientist with the Keller Science Action Center at the Field Museum, partnered and collaborated with over fifteen local museums, libraries, and history centers to create a series of three regional exhibitions. Tudor noted, “These organizations steward and celebrate the region’s heritage, yet most weren’t connected, and many were unaware of each other.” The working group, dubbed the Calumet Curators, collaborated to share their rich collections and tell a truly impressive regional story.

Through collaboration, the network designed three regional exhibits that served as the showcase for a particular theme. These themes included natural and landscape change, industry and workers, and the diverse cultural heritage in each neighborhood. Some of the artifacts included maps from Alfred Meyer’s geological studies, statues from Villareal, and steelworker paraphernalia; although Tudor had one in particular that she thought deserved to be highlighted. The item, a 4×9 foot, 800-pound steel plate, dubbed the “Rosie” plate. On June 4, 1943, several women who were steelworkers working at Inland Steel welded their names into the steel flooring plate in cursive. These women, evocative of the Rosie the Riveter mythos, had their piece discovered when some filing cabinets were shifted, revealing the artifact.

“Steelworkers flanking the Rosie plate.” Courtesy of J. Weinstein. © Field Museum of Natural History, 2019.

Taken together, the evening serves as a vital reminder of the region and much of the Rust Belt’s history. Perhaps nothing is more telling than the ending of the documentary. Shifting between photos and video of the Southeast side is footage of Walsh and his daughter. This cuts to a white screen with one word in black – “Hope.” Then another frame – “The beginning.” Walsh’s documentary and the exhibit highlight the crucial grassroots work being done by a passionate cohort of residents wanting to preserve the past and rewrite the region’s narrative.

A tapestry, entitled Steel II, created by Helena Hernmarck in 1973 and commissioned by Bethlehem Steel. Displayed at Field Museum as part of the Calumet Voices, National Stories exhibition. Photo courtesy of the author.

It was evident talking with Walsh and some of the attendees that there is a momentum of optimism in the neighborhood. Discussing the social movement scene, Walsh claims that “activists [on the South side] are top-notch, and it is such a good time to get rid of the misguided stuff.” This includes the effort of General Iron to move from affluent Lincoln Park to the Southeast Side. A move blocked thanks to the organizing of residents and a new cadre of young environmental justice activists. For Walsh, understanding this history makes it “painful to see how neglected the neighborhood was,” but with the community rising up, he can see that “grass is growing from industrial remnants.” Even the sharing of a regional history at a prominent location like the Field Museum offers a renewed vigor for telling the story of the region by residents of the region itself.

The Southeast Side, like many of its industrial neighbors, was a city forgotten. While many clamored to speak about the heyday of industrialization and its decline, the screening and exhibit showed that there is so much more to the region’s story. While often confined to the histories of Chicago, the broader region holds ample opportunity to speak to the mosaic of our national history. Our story did not end with deindustrialization. Our story includes the difficulty of this time but it is also balanced by our resilience to preserve.

Emiliano is a Mexican-American native of East Chicago, Indiana, and a staff writer for Belt Magazine. He is a lifelong resident of “the crossroads of America,” holds a few degrees from Midwestern colleges, and is currently in the Department of History at the University of Notre Dame. His first book project explores the complexities of the ethnic Mexican and Puerto Rican community’s navigation of machine politics in the 20th and 21st centuries to further their inclusion in municipal and union politics in his hometown. At Belt, Emiliano hopes to continue to elevate the stories of the region’s political history and its Latina/o residents.