By Todd M. Michney

The trim, brick and wood colonial at 15508 Talford Avenue is unassuming. Located in the southeasterly Lee-Harvard neighborhood, the house was built in 1947 and comes in at just under 1,200 square feet. Modest by today’s standards, it represents an earlier, post-World War II dream of suburban single-family housing – and stands as an object lesson on the troubling history of race and housing inequality in Cleveland.

Lee-Harvard is a ‘suburb in the city’ – one of several outlying neighborhoods fitting that description that lie within Cleveland’s municipal boundaries. Most of Talford Avenue’s initial residents were Czechs, Italians, Hungarians, Poles, and Jews who moved from closer in, identifiably ethnic neighborhoods – like Mount Pleasant, Corlett, and Glenville – chasing a more affordable version of the suburban lifestyle to be had in Shaker Heights, Maple Heights, and Garfield Heights. Many were young families striving after this newly-available version of middle-class respectability. Some of the men were veterans of World War II who now worked as skilled tradesmen or small proprietors.

K.C. Jones and Wesley Toles of the Cleveland Community Relations Board, 1960 (Courtesy of the Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University Library)

In July 1953, Wendell and Genevieve Stewart, an African American couple, purchased the house at 15508 Talford, touching off a furor that challenged Cleveland’s reputation for relatively placid race relations. Wendell Stewart was a mortician at the city’s largest black-owned funeral home, the House of Wills. He was a deacon at the prominent Antioch Baptist Church, a member of the NAACP, and a board member at the Cedar Branch YMCA. Genevieve worked as a retail supervisor and hosted a weekly radio program. Despite the couple’s solidly middle-class background, white residents’ immediate response was outrage. They rushed to harass the home’s seller, whom the local press described as “a Jewish businessman with a non-Jewish wife who … had sold the home to Negroes out of spite against his neighbors with whom he had had considerable difficulties.”

Motivated by a widespread belief that the presence of African Americans inevitably lowered property values, and cognizant of other instances in which initial move-ins by black families had catalyzed the demographic turnover of entire areas, hundreds of neighborhood whites attended nightly “mass meetings” at nearby Gracemount Elementary School, where speakers denounced the Stewarts and some present called for the use of violence to dislodge the couple. Other local groups, including the Cleveland Community Relations Board, Jewish Community Federation, and Saint Augustine Guild, attempted to calm fears among their respective constituencies and organized a letter-writing campaign in support of the Stewarts.

Despite the couple’s solidly middle-class background, white residents’ immediate response was outrage.

A neighborhood committee met with Wendell Stewart and his lawyers, alongside Cleveland Mayor Thomas Burke, in an attempt to de-escalate the situation. Once it became apparent that the Stewarts intended to stay, Mayor Burke made a public address to Lee-Harvard residents, where he told an angry crowd of over five hundred people that he would continue to provide police protection to the Stewarts and defend their right to the property. Through such interventions, and the courage of “pioneering” black families like the Stewarts, Cleveland maintained its reputation for tolerance into the following decade – in contrast to contemporary Chicago and Detroit, where this strategy of highly-organized white resistance played out with minimal intervention by local officials.

Yet in other respects, the subsequent trajectory in Lee-Harvard feels familiar. Talford neighbors grudgingly accepted the Stewarts after the tense first six months, but the house was vandalized on two occasions, and other African American families avoided Lee-Harvard until 1957. In 1961, however, a rash of “blockbusting” ensued. Aggressive real estate agents played upon white homeowners’ racial fears to generate rapid turnover, buying low and then selling at a substantial markup to black middle-class families desperate to improve their housing situations. In fewer than five years, Lee-Harvard was overwhelmingly African American; most of the remaining whites were either poor or elderly.

Wendell and Genevieve Stewart’s home at 15508 Talford Avenue in 1953, after paint attack by vandals (Courtesy of the Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University Library)

In evaluating this episode, we need to move beyond the conventional narrative of “white flight” – one that has subsequently played out, albeit with a diminishing role for racial confrontation and high-pressure sales tactics, in suburbs including East Cleveland, Warrensville Heights, Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights, Bedford Heights, Maple Heights, Garfield Heights, Euclid, South Euclid, and Richmond Heights. We need to go further back in time to better understand patterns of urban development and population dynamics, and take into account the overarching structural factors that constrained African American housing options and reinforced white notions about the supposed links between race and property values that persist to this day.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, outlying neighborhoods like Mount Pleasant and Glenville housed not only Southern and Eastern Europeans, but also small numbers of African Americans. By 1900, a compact black enclave was established around East 128th Street and Kinsman Road, which grew to 700 families by 1940. Meanwhile, African American families began moving onto the blocks off Glenville’s East 105th Street as early as 1915; by 1940, nearly 300 families lived there. Other outlying pockets of black settlement emerged in the 1920s – notably near the intersection of Lee and Seville Roads on the far southeast side, as well as around West 117th Street and Bellaire Avenue. Seen on this longer timescale, the Stewarts’ move to Lee-Harvard comes into focus: as the logical progression of African Americans’ search for living space. Upwardly-mobile blacks, excluded from the initial round of suburbanization in Cleveland, found a home in in outer-city “surrogate suburbs.”

In 1965, just 1 percent of Greater Cleveland’s African American population lived in actual suburbs, compared to approximately half today.

It’s not quite that simple – small pockets of black settlement already existed in suburbs, including Woodmere, Maple Heights, Berea, and Chagrin Falls. And African Americans began gaining access to bona fide suburbs around the same time that substantial numbers began moving to Lee-Harvard, starting with Shaker Heights’ Ludlow neighborhood in 1957. But for the moment, outer-city East Side neighborhoods would play a more significant role as expanding black residential areas. In 1965, just 1 percent of Greater Cleveland’s African American population lived in actual suburbs, compared to approximately half today.

The experiences of African Americans living on the urban periphery in the early twentieth century diverged from those of most blacks, who were consigned to densely overcrowded and increasingly segregated inner-city districts. Contact between African Americans and Southern and Eastern Europeans in outlying areas of the city was somewhat limited by blacks’ insular settlement pattern, although members of the two groups encountered each other in workplaces and shared the same public schools. The only major racial clashes that occurred at this time concerned black access to public swimming pools.

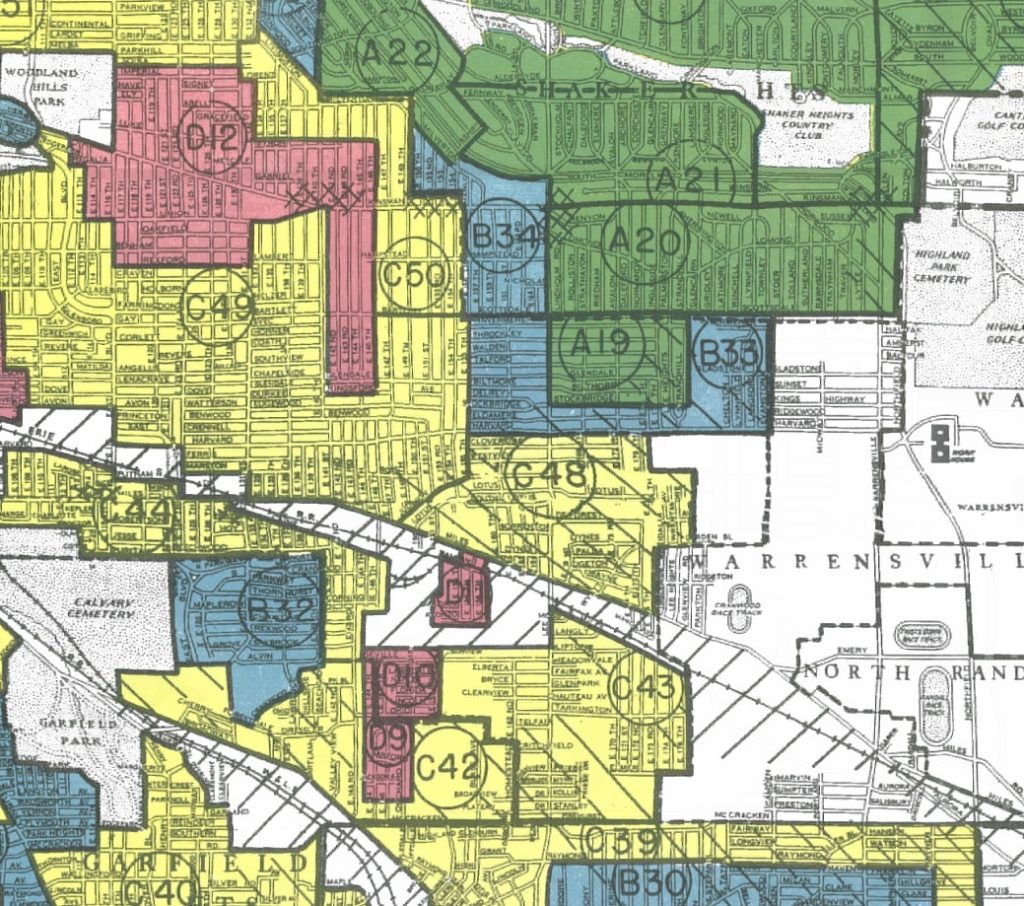

Southern and Eastern Europeans, like African Americans, were regarded negatively by real estate professionals and the federal government into the 1930s; the Home Owners Loan Corporation, the New Deal agency that commissioned a now-notorious collection of redlining maps, rated all neighborhoods inhabited by African Americans (regardless of class) as “red,” or “hazardous” for mortgage lending, while assigning a scarcely better “yellow,” or “risky” rating to those inhabited by Southern and Eastern Europeans. Large portions of Lee-Harvard had in fact received the latter designation, due to its substantially first- and second-generation immigrant population, the not-yet-standardized pattern of land use and housing design, and a widespread lack of deed restrictions (“covenants”) forbidding sale to racial minorities.

Detail of “Residential Security” (redlining) map created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation, 1940, showing Lee-Harvard area (Courtesy of the National Archives II, College Park, MD)

Southern and Eastern Europeans increasingly identified as “white” as they moved to further-outlying areas and experienced higher rates of homeownership. Such sentiments solidified further during World War II, when Cleveland absorbed an influx of black (and white) Southern migrants attracted by defense industry jobs, and immediately after the war when working-class whites were in a prime position to take advantage of preferential mortgage financing underwritten by the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration – assistance that was denied to African Americans except in the small number of all-black suburban subdivisions built around the country with FHA approval.

While working-class whites were empowered by federal housing policy, middle-class blacks struggled to buy outside of the tightly circumscribed urban core. This artificially-induced housing shortage fostered overcrowding that contributed to the deterioration of housing stock. “Invisible” government subsidies and visible evidence of physical decline in the neighborhoods where African Americans had moved formed a potent combination, serving to confirm white notions linking property values and race.

Before they bought on Talford, Wendell and Genevieve Stewart had owned a house in Glenville. During World War II, growing numbers of African Americans sought shelter in that neighborhood as landlords in the inner-city Cedar-Central district partitioned rental housing into smaller “kitchenette” suites for which they charged exorbitant rents. Besides its better-quality housing, the fact that Glenville was Cleveland’s largest Jewish neighborhood also played a role; Jews, unlike Roman Catholics, had no reputation for violently resisting African-American neighbors. The neighborhood’s black population skyrocketed from 900 in 1940, to 22,000 and growing by 1950, and the familiar pattern of landlords converting housing for multifamily occupancy – previously seen in Cedar-Central – became increasingly evident. It was concern about a declining quality of life, in fact, which motivated the Stewarts to leave this erstwhile black middle class stronghold for all-white Lee-Harvard in 1953.

Middle-class African Americans fought overcrowding and other manifestations of urban decline through organizations like the Glenville Area Community Council (founded in 1945), Mount Pleasant Community Council (1946), and Lee-Harvard Community Association (1957). Neighborhood activists working through these and other bodies – right down to the street and block club level – encouraged property upkeep and fought to enforce building codes, lobbied the city to maintain an acceptable level of services, restricted the availability of liquor through local option referenda, promoted viable commercial strips, monitored the quality of local public schools, and stepped up enforcement against crime and juvenile delinquency, even to the point of forming auxiliary police patrols. But white unwillingness to relinquish living space – particularly the refusal of mainstream banks, prior to the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, to lend on any purchase outside of already-established black residential areas – made such neighborhood-based reform efforts a constant and uphill battle. By the late 1960s, Cleveland’s outer-city neighborhoods were losing their luster for upwardly-mobile African Americans as federal civil rights reforms enabled increasing numbers of them to relocate to some of the already-mentioned suburbs.

15508 Talford Avenue in 2014 (Courtesy of Google Maps)

Lee-Harvard retains a core middle class population to this day, including many retirees. But since the onset of the Great Recession, the neighborhood – and Cleveland’s African American middle class more generally – have faced additional challenges. A disparity in the appreciation of home values on properties owned by black families fostered a yawning racial wealth gap over the post-World War II decades, with particularly volatile shifts since 2008. The house at 15508 Talford, for example, purchased by the Stewarts in 1953 for around $11,000, had an estimated worth of $89,000 in 2007, yet dropped to $68,000 in 2009. After tumbling to just $48,000 in 2011, its market value has stabilized to $63,000 today.

Cleveland was among those cities most powerfully affected by the housing market crash, even though no substantial housing bubble developed. Troublingly, African American homeowners were disproportionately targeted for predatory lending and subsequent foreclosure, including in suburbs like Euclid, Garfield Heights, Maple Heights, Shaker Heights, and Solon; one study found them saddled with subprime loans at two to four times the rate of white homeowners, regardless of income.

Until we acknowledge its role in fostering inequality, the racially-inflected history of housing in our country and cities will continue to haunt us. And its effects have been especially devastating in the former industrial powerhouses of the Great Lakes region. According to the 2010 census, Cleveland’s metropolitan area was the fifth-most segregated in the U.S., narrowly trailing Milwaukee, New York, Chicago, and Detroit. The loosening of racist housing restrictions came woefully late, once these cities’ economies were already hemorrhaging jobs. In our search for a new economic base, we must begin by first understanding how we arrived at this point. Perhaps then – and only then – can we begin to chart new and more fully-informed paths that do a better job of prioritizing equity and creating opportunities for all.

___

Banner photo: Meeting of the Lee-Harvard Community Association, 1979 (Courtesy of the Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University Library)

Todd M. Michney is a native Clevelander who teaches in the School of History and Sociology at the Georgia Institute of Technology. His book, Surrogate Suburbs: Black Upward Mobility and Neighborhood Change in Cleveland, 1900-1980, just came out on the University of North Carolina Press. You can follow him on Twitter @ToddMichney.

Fascinating history

Excellent article. We’re passing it around over here in the CSU Urban Education PhD cohort where we just Tuesday covered structural and cultural racism in urban housing. Thank you for your work.

Auburn Sandstrom

CSU Urban Ed Policy Studies

PhD student

Marvelous article .. hit the nail on the head.

Don Tomola. 3845 E188th

This is a powerful narrative demonstrating that sustainability in urban communities requires justice and equity for all. No matter what we build or where we live our quality of life and our resistance to dystopia depends on just sustainability.

Kermit Lind

Cleveland Heights, OH

I am trully learning Cleveland history.

Quick note: based on inflation numbers, the house in question actually lost value! $11k in 1953 is around $100k today, which means that house lost around 40% of its value. Amazing…

Great read. I grew up on DeForest Ave, about 1/4 mile south of Harvard just off Lee Road. My parents bought circa 1971 after leaving the Woodhill housing projects. Still have the house in the family. By the time they bought, the area was basically a “black neighborhood”; there were maybe two white families I could identify. I love the area still to this day.