By Kathleen Rooney

Every city is a text. You can read the city.

My favorite way to read Chicago is like a book of poetry. Not necessarily straight through but jumping around, page to page, focusing hard on one thing, then flipping past others, then focusing again, sometimes returning to the same spot, but in different moods and changing seasons.

The city offers pretexts. You can come up with reasons to go out and read.

When I feel restless in Chicago, I go out and read it. When I say “read” what I mean is “walk.”

Some people might say that Chicago’s sheer size — roughly eight miles east-west and 25 miles north-south — means that it isn’t a great walking city, but actually it is. Maybe not if you’re trying to walk as a deliberate means of conveyance from point A to point B on someone else’s schedule. But definitely if you’re interested in, as Guy Debord, philosopher and revolutionary, put it, “the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals,” aka psychogeography, aka dérive, aka a playful and observant drift through the urban landscape.

To say “I feel restless” is to say “I desire.”

To say “I feel restless” is to say “I desire.”

Longing is what drives me to walk in the city — but to want is not necessarily to be desperate.

“Lifeline” connotes differently than “the line of a life.” Chicago has offered both to me.

In his book Analyzing Everyday Texts: Discourse, Rhetoric, and Social Perspectives, Glenn Stillar discusses the texts that people encounter every day — “personal notes, brochures, advertisements, and reports.” In each case, he says, “the text is an impetus for our active response.”

Chicago is an unending ream of everyday texts — a letter, a sign, a receipt, a billboard, graffiti on the billboard, a sticker on the sign. It is an infinite occasion for active response.

One recent read-through of the city took place on a Tuesday — July 22, 2014 — the kind of hot summer day, thick with Midwestern humidity, when the doors are a little sticky and your lipsticks are a little melty.

The walk I took with my dériviste friend Eric took as its pretext raspados: grated ice confections, topped with either fruit or sweetened condensed milk called lecheras, sold from umbrella carts on the corners of 26th Street in Little Village. These are not snow cones. The vendors shave the ice with a tool called a raspador, a handheld rhomboid that looks like it would be at home on a carpenter’s woodworking table, and the toppings are not dyed corn syrup, but frutas naturales: coconut, guava, mango, pineapple.

The walk I took with my dériviste friend Eric took as its pretext raspados: grated ice confections, topped with either fruit or sweetened condensed milk called lecheras, sold from umbrella carts on the corners of 26th Street in Little Village. These are not snow cones. The vendors shave the ice with a tool called a raspador, a handheld rhomboid that looks like it would be at home on a carpenter’s woodworking table, and the toppings are not dyed corn syrup, but frutas naturales: coconut, guava, mango, pineapple.

It will take us seven hours and as many miles on foot, plus more by bus to get there, though, as we live on the far north side, Eric in Rogers Park and I in Edgewater.

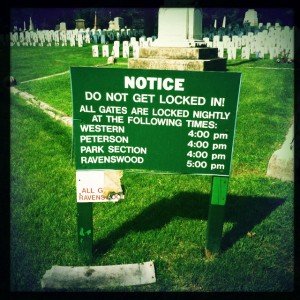

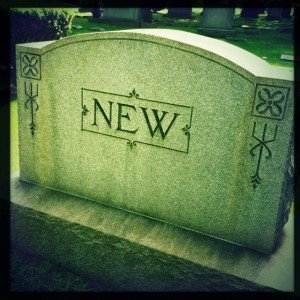

On our way, we cut through Rosehill Cemetery, 350 acres, built in 1864. Do Not Get Locked In, warn the signs. The Western and Peterson Avenue gates close at 4 p.m., the Ravenswood one at 5 p.m. Reading the headstones, it feels as though we’ve stumbled into the Cemetery of Near Misses: there’s an Irving Berlin, but not that Irving Berlin, and a James S. Kirk, one letter away from being the captain of the starship Enterprise. A huge monument says NEW, as if all new things had died.

On our way, we cut through Rosehill Cemetery, 350 acres, built in 1864. Do Not Get Locked In, warn the signs. The Western and Peterson Avenue gates close at 4 p.m., the Ravenswood one at 5 p.m. Reading the headstones, it feels as though we’ve stumbled into the Cemetery of Near Misses: there’s an Irving Berlin, but not that Irving Berlin, and a James S. Kirk, one letter away from being the captain of the starship Enterprise. A huge monument says NEW, as if all new things had died.

We stop at Nu Lhan on Lawrence near Lincoln Square, a hole-in-the-wall Vietnamese bakery, and pick up two veggie classic banh mi for just $4.95 each. We’ll eat them later on Montrose, near Kimball, on a bench on a street corner, and a mailman who looks like Willie Nelson will walk by and say, “An urban picnic!”

We stop at Nu Lhan on Lawrence near Lincoln Square, a hole-in-the-wall Vietnamese bakery, and pick up two veggie classic banh mi for just $4.95 each. We’ll eat them later on Montrose, near Kimball, on a bench on a street corner, and a mailman who looks like Willie Nelson will walk by and say, “An urban picnic!”

On our way to the bus we’ll take to the second leg of our pedestrian journey, we pass a pool hall called Marie’s Golden Cue whose ancient yellow starburst sign maximizes the game’s phallic comedy potential: We Have Smooth Shafts and Clean Balls.

The full route of the Pulaski bus goes 19 miles from Peterson to 31st Street. We catch it at Montrose and Pulaski and ride it to 26th. “Don’t let anyone steal your joy,” says the gregarious crazy man sitting near the front. We talk to him until he gets off “to make a delivery” at Grand. Before he leaves he will tell us that his name is Blanco and that he doesn’t tell that to just everybody.

The full route of the Pulaski bus goes 19 miles from Peterson to 31st Street. We catch it at Montrose and Pulaski and ride it to 26th. “Don’t let anyone steal your joy,” says the gregarious crazy man sitting near the front. We talk to him until he gets off “to make a delivery” at Grand. Before he leaves he will tell us that his name is Blanco and that he doesn’t tell that to just everybody.

We wander a couple miles along 26th among the taquerias and electronics shops and clothing boutiques whose mannequins have extra bubbly butts. We buy a pig bread from Los Gallos, then make for our destination, a raspados cart run by three hairnetted women who let us order our treats with not just one but dos saboras. Savoring them, we ride the circuitous beeline that is the Blue Island bus route from 26th and Kedzie to State and Madison, where we hop the Red Line north for our respective homes.

Inveterate flâneur Walter Benjamin described a state of perception he called “the colportage phenomenon of space” in which “we simultaneously perceive all the events which might conceivably have taken place here.” He named this after the practice of colportage, a system of distributing books, especially devotional literature, and other wares by traveling peddlers in France in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There are not many raspados carts left. One day, maybe, they’ll all be gone. For a while, colportage-style, maybe, people will perceive their traces; then one day they won’t.

The city of Chicago is an infinite book being written, erased, unwritten, rewritten, and erased again, all the time. Everything is always already on its way to being a ruin, or even gone completely. This is why, even though walking in Chicago can be said to make me happy, the color of the happiness has a blueish cast, tinted with loss and melancholy.

Eric and I take photos when we walk. This does nothing to save the city, to preserve it, really, at least not permanently. We know this. But what point has ephemera, except to be collected?

We’d walk through Chicago forever if we could and the things we love about it would never die or fade, but would stand for eternity.

The fantasy of perpetual motion is the fantasy of immortality.

Kathleen Rooney is a Chicago-based writer. Follow her @kathleenMrooney or visit her at kathleenrooney.com.

Support paywall free, independent Rust Belt journalism — and become part of a growing community — by becoming a member of Belt.