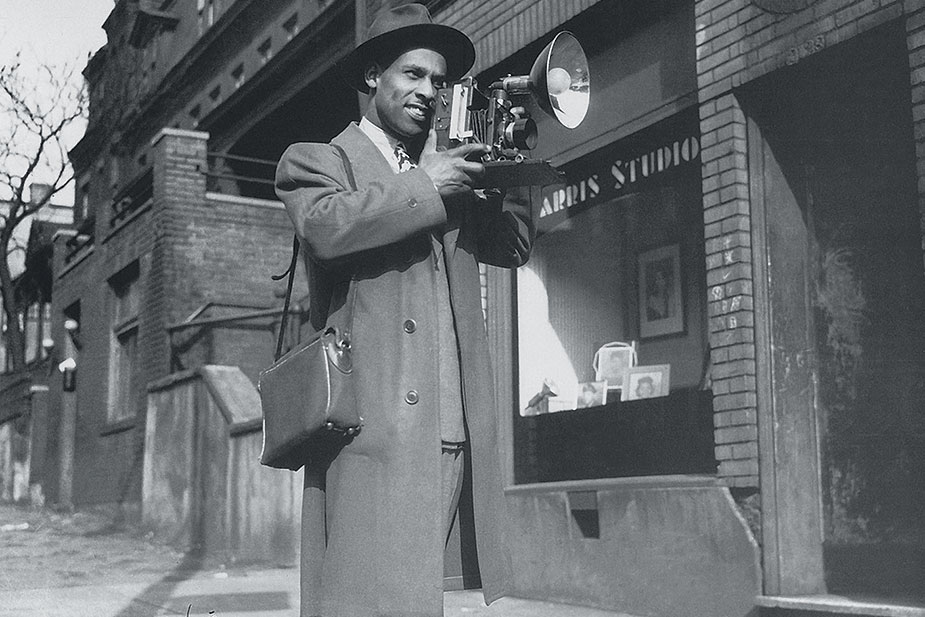

One of Harris’s many gifts was his ability to capture expressions—smiles, scowls, and all the nuances in between.

By Emma Riva

Joy slips through your hands. Anger, malaise, and fear are heavy, long-lasting, but joy’s lightness and effervescence means it’s a lot harder to hold down. Think of how the one criticism stings more than ten compliments could ever glow, or how a torrid affair with someone who mistreats you sends you down an emotional spiral more palpable than the security and peace from the kindness of someone who really loves you. Really feeling joy, as deeply as a sting or a spiral, is challenging. Pittsburgh-born photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris managed, through his camera lens, to picture those glimmers that are so often so fleeting.

The Carnegie Museum of Art is in possession of a large swath of Harris’s work, per his wishes upon his death, but for many years they were relegated to bad exhibition real estate. Harris’s photos were once in a hallway leading to an elevator, or in the basement, or in a shared back gallery with another artist. But as of November 2024, the museum has dedicated a full gallery to the Charles “Teenie” Harris archives. They plan to exhibit every item in the archives over time, swapping things out over the years and giving Harris’s work the center stage it deserves.

I worked for the Carnegie on the gallery floor at one time, and one of my favorite pieces to observe was Aaronel deRoy Gruber’s portrait of Harris, in his eighties. He’s pictured doing a high kick in front of his house in Homewood (now a historic landmark in the city of Pittsburgh). Even in old age, Harris brimmed with life.

It’s significant that the archive is in Scaife Gallery 7, if you’ll allow me to give a museum insider’s point of view for a moment. This is a significant space because in the aged behemoth that is 4400 Forbes Avenue building, the second floor where the majority of the collection is only has one set of bathrooms, in Scaife 7. Everyone goes to Scaife 7 at some point in the museum, young and old, because nature calls for all of us, especially on long days of looking at art. Harris’s archival work went from under-trafficked corners to the highest foot traffic space in the art museum. It’s a long overdue upgrade.

Over a thousand people attended the opening celebration to the Harris archives, with jazz by Roger Humphries and the RH factor accompanying a day-long event. The archive’s gallery guide is printed like a newspaper. It’s become a bit hackneyed to call anything “a love letter to the craft,” but Harris’s photojournalism is as close as one can get to a love letter to the craft of reporting. Journalism is often a thankless, draining job. Only someone overflowing with vivacity, curiosity, and zest for life can really thrive in it. In contemporary life, when the craft is so reduced to clickbait and infighting, Harris’s photojournalism is a reminder of why we got into this business in the first place. I became a journalist because I love life. I studied fiction but found I couldn’t relate to people that didn’t care about the everyday lives of their peers, who didn’t seek out joy in telling stories just for stories’ sake. Harris’s work, and the Pittsburgh Courier’s more broadly, speak to the power of community-focused reporting.

One of Harris’s many gifts was his ability to capture expressions—smiles, scowls, and all the nuances in between. The video element of the new gallery is its crown jewel, a rotating slideshow of Harris’s photos blown up to huge proportions. Some are still images, others are videos Harris took. A glamorous young woman eats a scone and drinks from a glistening bottle of sparkling water while sitting outside a storefront. Someone plays with a kitten in a field, only their hands visible as the kitten rolls around in the grass. On the walls, Walter Hamm of Hamm’s barbershop in the Hill District poses beside the hood of his car, suave and confident but not stony.

Harris photographed everyday people, but also Jackie Robinson, Shirley Chisholm, and almost every mid-century jazz musician you can think of. His images of the Loendi Club, an exclusive social club in the Hill District, are poignant snapshots of the glamor of Black middle-class life in the Hill. I found that as I looked at Harris’s photos, it made me pay more attention to details in the people around me. People dressed up for the opening celebration, sure, some a little more comfort than couture, but nobody looked shabby and everybody looked happy. Art museums aren’t typically sights of bustling crowds, but on that Saturday in November, one was.

Charlene Foggle-Barnett, the archivist who spearheaded the new gallery, was a contemporary of Harris’s. Harris photographer her and her parents, siblings, and cousins throughout the year, and in the archive itself you can watch her grow up. She made sure that the exhibit featured a timeline of Harris’s life and supplemental materials on Black history in Pittsburgh. There are also original negatives of Harris’s film, an example of the camera he used, and old copies of the Pittsburgh Courier to give viewers context about what they’re seeing. Though the archive is in one room, that room contains so much history that one could spend a whole week in it, pouring over the materials. A guestbook allowed visitors to respond to what they saw, and I was struck by one woman named Carmela’s note that she’d worked with Harris at the Courier and remembered him as “smart, friendly, and so talented.” The phrase “living archive” is another that feels hackneyed to me, but the Harris archives are deeply alive.

Pittsburgh’s art history is oversaturated with Warhol. He has his own museum, and if you ask most people to name a famous artist from Pittsburgh, they’ll know Warhol, if any at all. I found myself wondering what a Charles “Teenie” Harris museum would look like to rewrite the narrative of Warhol as Pittsburgh’s creative bastion. Warhol himself disdained the city, and the museum dedicated to him hasn’t always felt full of life. The Harris archives show another way to present art history, and I hope this is only the start, as more people are introduced to his work. Throughout the opening, The Carnegie’s on staff photographer took photos, and I mused over what it was like to photograph people looking at Harris’s photographs. That then creates a new living archive, one of joy.

Emma Riva is the managing editor of UP, an international online and print magazine that covers the intersections of graffiti, street art and fine arts. She is also the author of Night Shift in Tamaqua, an illustrated novel set in the Lehigh Valley. She lives in Pittsburgh, PA.