By Bridget Callahan

The building is one of those beige, ’80s office numbers, and through the half-shut blinds, cars are whizzing past on Interstate 480. It’s a beautiful day in April, and in the darkened classroom, the teacher is doing a midterm review with the students, going through slides of vocabulary and textbook photos.

“And what’s this part here, where the old stem meets the new stem?” the teacher asks the class.

A young woman in business casual answers first. “The node,” she says.

“Right. Okay, and then, what do we use them for?”

This time a young man who looks right out of high school and is sitting up front in the first row answers.

“To tell the sex of the plant.”

“Right, good,” the teacher says. “Now, next time, don’t just throw the stem in the ashtray, take a look at it first.”

The teacher takes advantage of the small laugh to remind them about the extra credit on the exam.

“It’s a one-hour video, all about soil mixes, and if you watch it, it’s 15 points extra credit if you do the essay, but you can’t do the essay if you don’t watch the video,” he warns.

The Cleveland School of Cannabis is the only state-approved career school for cannabis east of Denver, one of only two in the whole country. Started merely a year after Ohio legalized medical marijuana, the school offers three separate certificates, or majors, in Cannabis Horticulture, Cannabis Business, and Medical Applications of Cannabis. Students can also opt for the Executive program, which gives them an accelerated course in all three. Classes include basics like Business 101 and History of Cannabis, major-specific courses like Commercial Cultivation Operations, and electives like Extracts Manufacturing and Processing.

The students in the Cultivation class at the CSC don’t seem worried by the fact that Ohio will likely not meet the deadline to get medical marijuana up and running by September, a roll-out that has been plagued by persistent legal troubles. Many of the cultivation centers had already started reaching out to the school to set up hiring referrals in May, according to the school. Mary Jane Staffing, which specifically focuses on cannabis-related jobs, estimates that the initial industry start-up in Ohio will result in 2,000 jobs right off the bat, the majority of those full-time. And that’s only counting jobs directly in the industry, not ancillary businesses. Overall, Frontier Data estimates there are 230,000 people working in the cannabis industry nationwide, a number that will only grow as more and more states legalize.

“…there’s a huge swath of legitimate, professional, well-rounded people who are dying to get in the industry in some way because they love the plant and the culture, and what it’s done for either them medically or their loved ones.”

An older woman, Jan, says her family laughed when she said she was taking the course. But seeking a career in medical marijuana fits neatly with her interest in natural foods and medicines.

“I mean we’re not pumping out cars anymore, and just because my father worked at a factory doesn’t mean I have to, or can. These young kids, they need a future,” Jan adds, gesturing slightly towards the messy-haired young man.

Each major requires 136 credit hours, which translates to three classes, two electives, and two required courses, one of which, the Medical Cannabis Comprehensive, is an intense, weekend-long survey course. The school recommends taking the MCC first before enrolling in a certificate program, to help students get perspective on all their options.The MCC costs roughly $350, a fee that is then applied to tuition if the student enrolls in a program. Each complete program costs about $6,500. Not too bad for a trade school, but will it get them a job? And what kind of job will it be?

A majority of new students are interested in horticulture, perhaps because it’s the most recognizable field in a new industry; most people have a simplified image of the legal weed industry just as some goofy guys growing plants, not as the sophisticated consumer sector it is, with hundreds of different possible jobs. It’s akin to knowing you could be a nurse, but not imagining a medical assistant, or a PA, or an X-ray tech.

“Most of them want to work as cultivation technicians, or as a processor, or making edibles. There’s a huge range of where people are going, but horticulture is the most popular,” says Sam Brenkus, a horticulture instructor at the CSC. “For a cultivation technician, that’s an entry level job, so most of those are $15-$20 per hour, but for management, a cultivation manager can range from $80,000-$100,000 plus equity.”

Austin Briggs, the school founder, gives the pitch to new students at an open house. Ronald Hudson, owner of Mr. McGooz Canna Products, sits in the back of the classroom. Mr. McGooz is a partner with the CSC, and Hudson is on the board. Briggs points him out to the potentials, as an example of employers watching and waiting for them. Hudson is heavily involved with the school, often coming in to speak with students. He says it can be hard to find qualified workers, especially in the edibles industry, where doses must be precise.

“What recreational marijuana hitting the market has done that medical marijuana could not do is mandatory testing. It was never really enforced. The FDA doesn’t control it, so the attitude was ‘Hey, someone gets sick, we deal with it on a one by one basis,”’ Hudson says. He believes recreational is forcing the whole market to get professional about regulations, and employees who have a certificate will be first in line for the best paying jobs. “What makes this school so important is the East Coast hasn’t even seen the boom yet,” Hudson adds, “ I don’t believe anyone coming out of this edibles course here will go onto a testing floor and make less than $50,000 or $60,000 a year.”

Briggs says he didn’t realize when he decided to start the school in Ohio, how many ancillary cannabis industries were Ohio-headquartered, providing graduates other job opportunities even before the cultivation centers open.

“I was surprised at how many leading companies in the industry were already here. In nutrients, in lighting, in packaging, in publishing. Cannabis Business Times is one of the leading publishers in our industry and they’re actually located in Valley View. Scotts Miracle-Gro is in Ohio, which owns companies in soil nutrition, and then we have Eye Hortilux, which does indoor lighting, and Apeks Supercritical, which manufactures extraction machines,” Briggs notes.

Briggs is an Ohio native himself, who grew up in Cleveland Heights and went to Kent State. In 2013, while living in LA, he invested in a friend’s new cultivation facility, his first foray into the medical marijuana industry. With his degree in entrepreneurship, and a background in real estate, Briggs was immediately interested in the new industry, but wanted to learn more, and that’s where he hit a snag. For all the boom, there are very few places to actually go and learn the ins and outs of the industry. He went to a weekend seminar in Oakland, a kind of beginners introduction course, but it felt too cursory. Most of the cannabis education out there comes in the form of these traveling weekend or day classes, often set up in hotel conference rooms. They are surveys, not deep dives into the material and culture.

“I recognized the need then, but I wasn’t thinking about an educational program yet,” Briggs says. “I basically had to just hang out and get more involved, learning it on my own. I found out it was just really hard to find qualified workers, especially in cultivation sector where if you yourself didn’t know cannabis cultivation, it was really hard to judge. Nobody was coming in and saying I have a degree in this or I learned it somewhere, you’re just going off their word. From an employer’s standpoint, they really need a place to get qualified workers from.”

Credit: noexcusesradio via pixabay

Getting state approval was a process requiring patience, time, and money, since all the state infrastructure around cannabis is brand new. Did, for instance, cannabis education fall under the oversight of the Medical Marijuana board or the Board of Career Schools and Colleges, for instance? (The BCSC won that final verdict.) Now that they can finally say “state-approved” on their ads, enrollment is starting to pick up.

Donelle Watson, the Director of Advising and Student Success, meets one-on-one with every student when he enrolls them, to feel out their past experience and current goals. He confirmed the demographics of the students are diverse. Of the 85 students currently enrolled, 36 are women and 49 are men. The oldest student enrolled is 72, the youngest just out of high school. But the students overall, and the people showing up at the open houses, have a strong contingent of baby boomers.

“I think you’re going to find that more and more,” says Ezra Parzybok, author of Cannabis Consulting: Helping Patients, Parents, and Practitioners Understand Medical Marijuana. “The baby boomer generation is the fastest growing consumers of cannabis. When they were in college, they smoked a few joints and they thought it was fine, and now they think hey wait, I can actually make a living getting into this field? Some of my buddies are trying to start up businesses? So I think it’s very attractive to the older crowd.”

Parzybok is a cannabis consultant and patient advocate, who assists companies with starting up businesses in his home state of Massachusetts, which will roll out recreational weed this year. He knows what employers are looking for.

“If someone has a certificate, what it says to me is that they are serious enough to have gone and paid for a class and learned things,” he notes. “I do get frustrated with schools and the industry because there is a real sense of yes, we need education, and it’s filling in some of the holes, but I’m skeptical of schools that are teaching medical professionals about cannabis, because I’ve always maintained that cannabis occupies this middle ground between pharmaceuticals and the herbal industry. And the people who are the experts in cannabis are the ones who have been essentially illegally growing it in their homes and providing it for patients for years. So to all of a sudden just have a nurse get a certification about what cannabis does and doesn’t do is fine, it’s just that there are people who are very qualified who have not come out of the woodwork.”

“It does bring up issues around who is an expert and who does have knowledge. But I think that schools on the whole are very important and will eventually flesh out their curriculum in a way that makes people well-qualified for the jobs they seek,” he adds.

The issue of hiring in the medical marijuana industry is a touchy one. People with the most experience in the field can’t exactly put their years of illegal cultivation on a resume. Massachusetts has chosen to get around this with a regulation that requires a background check, but also gives anyone with a prior drug offense the chance to come before the Cannabis Control Commission and explain the circumstances of their charge.

“I think that’s a positive step,” Parzybok notes. “They’re saying, ‘Look we understand that people who are already in the industry illegally will seek to be legitimate in the industry.’” Parzynok agrees jobs in the field fill up quickly, and that dispensaries and cultivation centers often have very competitive candidates apply.

“In the industry, they have their pick of really great people,” he says. “Because 10 percent of the American adult population consumes cannabis. This is an enormous number. The Snoop Doggs and the Cheech and Chongs of the world represent about 1 percent, because they’re the loud, aboveground people. The other 9 percent are the teachers, lawyers, doctors, professionals in your community, who just choose not to share their experience. So there’s a huge swath of legitimate, professional, well-rounded people who are dying to get in the industry in some way because they love the plant and the culture, and what it’s done for either them medically or their loved ones. I actually think as soon as a legitimate shop is up and running and wants to hire people, they will have a very easy time selecting really good people.”

Which is a pretty strong argument for a formal, cannabis-focused education if you want one of those coveted jobs. Gotta stand out from the competition somehow.

Of the 85 students currently enrolled, 36 are women and 49 are men. The oldest student enrolled is 72, the youngest just out of high school.

The school’s first official graduation ceremony was in June, but even before then there were some graduates floating out there in the world. Andrew Hamerly is one of them; he received his degree in innovation and entrepreneurship from Baldwin Wallace University last year, but was already involved in the industry through his glass blowing business that he started with a friend in college, selling pipes and pieces at festivals. He majored in the horticulture cultivation program, because he thought it would compliment his business degree. Hamerly did the program for six weeks, Monday through Friday, and then went straight to working full-time. Now he works at a conventional greenhouse.

“A high school friend of mine told me about the program, they went out to Oregon for the Trim for Training program, [an out of state internship offered] and really liked it. So I thought I’d give it a try. My main motivation was networking, ‘cause like I said, I’d been in the industry before, so I figured it would be a good way to connect to the right people who had the passion I had as well,” Hamerly says.

He says there are quite a few people he met in class that he’s stayed close to, One is the owner of a local organic urban farm, who introduced him to the Cleveland aquaponics scene. Another student helped him set up his own aquaponics system, which he uses to grow strawberries, tomatoes, and kale.

“One of the teachers at CSC, Christine DeJesus, has a one-acre organic farm that grows produce and pumpkins for Great Lakes Brewery for their beers, and they in return give her their beer waste, which she then composts and uses as organic fertilizer. I learned a lot from her,” Hamerly says. He adds that while his long-term career goals aren’t necessarily in the industry, he feels that what he’s learned has applied to all different areas of his life, and has definitely landed him the job he has today.

Briggs has plans for the school, and he’d love Ohio investors to get behind him. Most of the capital they’ve raised has been from Western investors, where the industry is more understood and accepted. Briggs is waiting for Midwestern investors to open their eyes.

“We would like to expand in 2019, we want to be in both Columbus and Cincinnati. By 2020 we’d like to have a national program. We’re looking to expand the courses, and launch our online programs. That’s what’s on the horizon for us before a national accreditation, which is also hopefully in our future,” Briggs says.

Credit: Bob Doran [https://www.flickr.com/photos/humblog/]

That open house was packed. Barb, the sparkling front desk receptionist who seems to run everything, says they have meet and greets once a month, and lately every time they’ve ended up moving the overflow to an upstairs classroom and doing a few sessions back to back. Among the people I met in that session were a recent high school graduate from Parma who is interested in opening a dispensary and wants to learn the legal side, an older couple made up of a massage therapist and her husband recently retired from the Ford plant, a young woman who is a pipefitter, and has family in Detroit already working on the supply side, an older man from Edgewater who is interested in patient advocacy, and a clean-cut chemist from Youngstown who with a double major in business. The backgrounds defy generalization. Some are just curious. Everyone recognizes an opportunity.

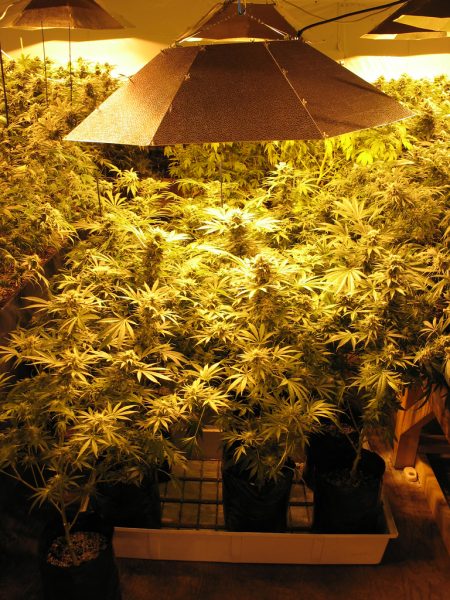

Back in the classroom, the teacher is quizzing the students about grow lights.

“And what kind are these?” he asks, gesturing to the slide.

An older woman answers. “Those are high pressure sodium lights,” she says. “But I don’t like those.”

“Oh, what do you use?” the teacher asks.

“I run T5s at home, have been for years,” she replies. The two get into a rather technical discussion about light bulbs, and I take the opportunity to whisper to my seatmate in the back of the room. She’s a stay-at-home mom in her late twenties, with a background as a medical assistant.

“What program are you doing?” I ask.

“I don’t know yet,” she whispers, pulling out her lip gloss. “I thought I’d just take some classes and see what I liked, see if I could get some direction.”

“Is it hard?” I ask.

“It’s not easy,” she replies. “I’m worried about these midterms. I think I took too many classes right off the bat. I think I’ll sign up for less next semester, if I’ve figured out my major. If I can get through this week.”

Proving some things about school never change.

Bridget Callahan is a writer who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, and now resides in Colorado. The fact of her relocation had nothing to do with weed, and everything to do with mountains. Her fiction and non-fiction can be found in MonkeyBicycle, Sheriff Nottingham, the Tusk, the Cleveland Urban Design Collective’s anthology Cleveland Stories: True Until Proven Otherwise, and Belt Publishing’s anthology Red State Blues. She can be followed on Twitter @bridgetcallahan

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the people of the Rust Belt, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.