By Jan Worth-Nelson

In the summer of 1961, my family moved against our will to a smelly brickpile of a parsonage in Akron, Ohio, where my father became the pastor of a church named for the crucifixion. And when we got there, we found ourselves surrounded by ghosts.

Some memories so vividly endure. Here is one, the beginning of this story: Canton, Ohio, a humid sunny day. I was 12, and even now, this moment remains clear and disconcerting. I am swinging on a gate outside our parsonage on Gibbs Avenue. I hear my mother take a phone call in the kitchen. It is my father, at the annual conference of his denomination, then grandly called the Evangelical United Brethren. (I have often thought since of the blunt absence of the word “sisters” there).

“No. No…,” I hear my mother exclaim. “Akron Calvary?” She moans, “No…”

*****

Later, I imagine, she must have pleaded with him. Not that church, please. Not that street.

[blocktext align=”right”]“No. No…,” I hear my mother exclaim. “Akron Calvary?” She moans, “No…”[/blocktext]Of all the places we could have been moved, that church and the street on which it stood were, for my mother, particularly, exactly the ones she ardently wished to avoid. For her, our journey there was thickly charged with ambivalence, nostalgia, loss and sadness.

For my father, the outcome was not much brighter. For him, the move to Akron triggered a decade of professional failure and spiritual doubt.

We had been happy in Canton, the church there a stately Georgian, pillared edifice with a smaller, matching parsonage next door, its own white columns topped with Ionic curls. Almost daily I climbed a maple tree in the front yard. I still dream about that house and leafy neighborhood.

But the denominational boss was retiring, and he wanted the Canton church, a buoyantly successful one, for his retirement reward. He pulled rank, and my father, shocked, angry but intimidated, did not know how to fight back. And the Akron church, others told him, was also big and impressive and possibly a step up.

But it wasn’t. And my mother’s intimations, rooted in a weave of childhood trauma, cast the appropriate sour flavor on our move.

But we restlessly took possession – “settled in” doesn’t capture it right – into the gloomy mansard-roofed parsonage at Akron Calvary. The church and parsonage stood coated in black rubber dust in a neighborhood years ahead of Canton in its uneasy transitions to poverty, core city deterioration and “urban renewal.”

What twisted this shock all together into a psychological and spiritual knot was not just my father’s humiliation, but the fact that every day in Akron we moved uneasily among the ghosts of my ancestors, prominent Akron pioneers who had homesteaded a large plot of land across the street. It was a cruel irony.

Family gathering in front of the Thornton homestead on S Main St. in 1902. Grandmother Amy Youtz Vandersall third from left standing, in a white dress. Courtesy of the archives of the late Frederick Thornton.

I went to a junior high named for the street named for my great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side, Samuel A. Thornton. He came to Akron from Pennsylvania, and in his 53 years in the mid-19th century bought two farms, built two large homes, and sired 11 children. As it happened, I took a year of Latin, quaintly, in a dingy first floor classroom whose windows faced land he had farmed, land eventually dispersed among his heirs.

One of his children was my Great-grandmother Matilda, who married a man named Winfield Scott Youtz. They lived in a Victorian house at 793 Coburn Street behind the Thornton estate. There they raised five children, including my grandmother, Amy. And that house on Coburn Street, where my grandmother had grown up, was right across the street from the church and parsonage where we were reluctantly installed in 1961.

When my grandmother grew up she married a man from Akron Calvary, Austin Vandersall. They said their vows in the sanctuary of the church where 60 years later, my father was to preach.

******

My grandmother’s family home on Coburn Street was haunted by its history. In 1904, six years before my mother was born, my Great-grandfather Youtz walked out of the house early one Monday morning, went to his sister’s place on Black Street, and shot himself to death with a .22. One grisly detail: the authorities brought his body back to 793 where his wife Matilda and children had just been notified. I can hardly imagine their trauma as they saw his wounds – one to the abdomen, and the fatal one, to the head.

My great-grandfather’s suicide, emerging as it did from the lives of the well-known Thornton family, was top of Page One news in the Akron Beacon Journal in an article passed down through the generations from cousin to cousin. Its luridly plastered four-part headline declares “SENT HIS SOUL SPINNING INTO ETERNITY – W.S. Yountz (sic) Deliberately Takes His Own Life – SUPPOSED TO HAVE BEEN DERANGED – First Bullet Failing, Another Was Fired Into the Brain.”

It continues, in sensational style, under the subheading “Man’s Strange Actions,” “It was thought that continued brooding over fancied domestic troubles was what prompted him to take his own life, as he had several times during the past few months threatened to his family to do so. It is the general opinion of the people residing in the vicinity of his home that the man was mentally deranged, as he has been seen in fits of rage at various times with no apparent reason.

“His wife has been the particular object of his attacks, he fancying that she was being familiar with other men, and last Friday he became incensed at some word of hers and literally kicked her out of the house in the dead of night. Returning the next morning accompanied by an officer, Mrs. Youtz secured her belongings and has since been staying with her mother, Mrs. Thornton, at the latter’s residence on the corner of Main and Thornton Streets. Although Youtz has been very despondent since that time, he left the house Monday morning in a cheerful frame of mind, and said goodbye to the children, who suspected nothing of his intention.”[1]

******

The Youtz family inside 793 Coburn Street (1897). Back row, left is Amy, my grandmother. Winfield Scott Youtz, her father, the man with the mustache of course, is the one who committed suicide ten years later. Courtesy of the archives of the late Frederick Thornton.

After Winfield Scott Youtz’s death, my Great-grandmother Matilda, his widow, stayed in the house on Coburn Street for another 30 years until her death in 1935. I don’t know how to put this, except to quote my mother, that she was known as “an old battle-axe” and within this painful story was always the suggestion, a deeply uncomfortable part of the myth, that she somehow drove her husband to it. It’s a claim vigorously interrogated by my generation of Thornton-descended feminists. Or at least by me. The truth is hard to divine; these were complicated people and mental illness was hardly met with enlightened care.

Though my mother never lived in Akron until we moved there in 1961, when she was a child her family often came to Akron, usually to stay at her Grandmother Youtz’s house on Coburn Street. It was, as she remembered it, a place of ambivalent escape from what turned out to be her own tempestuous family life.

Matilda Youtz’s daughter, my grandmother Amy Vandersall carried out the clan’s conjugal jinx. It’s another long story, but in brief, at some point my charismatic Grandfather Vandersall left his respectable parish in Findlay and launched himself as a traveling evangelist. This careening career change layered my mother’s childhood with fearful penury and domestic uncertainty. The family sometimes came to Matilda Youtz’s house to get good meals during periods when my grandfather was off eating pie at some out-of-state preaching gig – so those trips to see her grandmother undoubtedly were accompanied by a lot of tut-tutting about Austin Vandersall’s abandonments of his children and wife in the name of the Lord. Despite their own reduced circumstances, my mother said, they were proud to be part of the Thornton family tree, even though many of the women seem to have been bedeviled by flawed and unreliable men, secure in early 20th century Protestant patriarchy.

After her husband’s death by suicide, Grandma Youtz apparently lived relatively quietly, receiving visits from her 13 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. When she died in 1935, my mother, who was 25 at the time, came to the funeral from her teaching job at Elmore, meeting up with her sister and brother. She noted it in her diary, which I still have. Matilda Youtz is buried in Glendale Cemetery. Her obituary relates that she was a life member of Calvary Church and one of the few surviving pupils of the “old Stone School at Broadway and Buchtel Avenues.”[2] The circumstances of her husband’s death 31 years before were not mentioned. But her son Claremont’s mental illness already was evident.

******

By the time we arrived on Coburn Street, Grandmother Youtz’s house was beat up and boarded up. Every day when my mother looked out from our parsonage to 793 Coburn, she remembered. There was no way to avoid it.

All her life my mother heard admiring stories of the Thorntons in their pioneering energy and promise – and the degradation of those possibilities, the reminders of continuing struggle, in her grandmother’s generation and beyond. The very sight of that house exacerbated my mother’s persistent depressions, the ancestors’ formidable presence like a murder of crows still there, cawing out their yearnings, failures and woes, their melodramatic lives always tickling at the backs of our necks.

******

And thus our Akron narrative began.

When we moved into the parsonage, a “sunroom” at the front of the house, which should have let in needed light, was coated with rubber grit and smelled like cat pee – a gift of the preceding minister’s pet-loving family. We used to scrape black dust off the windowsills, and my mother found the heavy scent of rubber physically demoralizing.

We got visited regularly by “tramps,” as my mother called them — I remember one in particular with a huge corona of wild red hair — and my mother gave them tuna fish sandwiches at the back door. Despite his altruistic leanings, the “tramps” frightened my father, so he disapproved of my mother’s charity. He said the “tramps” must have marked the house because they kept coming, more of them more frequently. He finally made my mother turn them away.

******

My father plunged into spiritual and professional crisis. He was at heart an unworldly Indiana farm kid, an earnest descendent of Quakers and Nazarenes. He did not relate well to the parishioners, who seemed to him to be a “white flight” gang more interested in golf than reaching out to the community most of them had escaped for the suburbs. My brother remembers an awkward outing to a country club, where my father, trying to make inroads, and my brother, an engineering student home for the summer, sat sipping Cokes at the bar while the other guys heartily drank beer after what can only be imagined as an embarrassing 18 holes. After the first year, the home office sent my father to a two-week workshop designed to help pastors get hip to the Sixties. They heard about the “God is Dead” movement, and were presented with contemporary literature: in particular, Rabbit, Run and Henderson the Rain King. Neither book was a help to his evangelical doubts – he only found them anxiety-provoking and confusing.

Our garage was repeatedly vandalized – my brother’s prized bicycle stolen, sand inexplicably poured into the gas tank of my father’s car. My father kept finding piles of girlie magazines behind the church. I remember him furiously burning them in a rusty barrel.

My father planted flowers around the parsonage – red begonias – and I never see a red begonia without remembering his desperate need for something lovely. They didn’t thrive in the stony dirt, even though my great-great-grandfather apparently once found something fertile there.

More than once, my mother pleaded to be taken to the “mental hospital” in a florid menopause that afflicted her with paralyzing depressions. My father refused, and their relationship played out bleakly, silently after that. She got a job briefly as a high school home economics teacher, but lasted only six weeks before collapsing in failure: she said couldn’t handle the students, whom she found profane, puzzling, resistant and mean.

I got my first period, got mugged in the girls’ locker room, babysat for my math teacher, got straight A’s, and became best friends with a Chinese girl who lived across from Goodrich above her father’s laundry. She was crazy about Van Johnson.

Once my mother and I walked downtown from our parsonage to take a basket of apples to Jean Yee’s family. As we walked, my mother kept getting panhandled from greasy guys loitering in front of the old Goodrich plant. My mother nervously gave each one an apple. By the time we got to the laundry, the basket was almost empty. I don’t remember what we told the Yees.

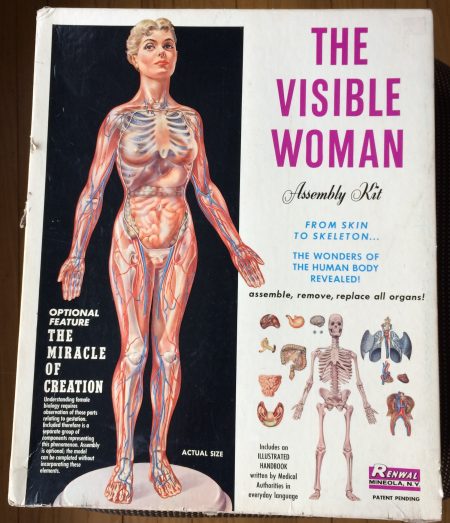

I put together a Visible Man and a Visible Woman, gifts my parents thought would supplement my learning at what they worried was a substandard school. My father helped me, but was embarrassed and uncomfortable with the anatomically correct parts. I remember there was a regular stomach and a pregnant stomach for the woman, and there was a fetus that I loved that fit inside the pregnant stomach.

I put together a Visible Man and a Visible Woman, gifts my parents thought would supplement my learning at what they worried was a substandard school. My father helped me, but was embarrassed and uncomfortable with the anatomically correct parts. I remember there was a regular stomach and a pregnant stomach for the woman, and there was a fetus that I loved that fit inside the pregnant stomach.

For my birthday in 1962, my father bought me a Roget’s Thesaurus, a book I adored and still have. He inscribed it, in his beautifully ornate handwriting, “To help you find words with which to express the thoughts of a very fine mind.” Those words meant so much to me – even now, 53 years later, as I try to express the significance of what happened on Coburn Street.

For another birthday, my parents bought me the World Book Encyclopedia – a wondrous gift, beautiful beige and green volumes with gold letters. I lined them up in a bookshelf in my bedroom and spent hours leafing page after silky page. It was a great escape.

******

The madness that led to my great-grandfather’s suicide seems to have followed into succeeding generations. Claremont, the only son, spent most of his adult life and died in a mental hospital in Massillon. His daughter, my grandmother Amy Youtz, exhibited symptoms of bipolar depression. In the next generation, one of my uncles suffered a breakdown, and my mother struggled with untreated depression. In my generation, one cousin has the gene, being long treated for mental illness despite immense accomplishment. Several other cousins are similarly if not so severely afflicted – and I myself have had several bouts in adulthood with panic attacks and depression. Perhaps it’s just life or the luck of the draw, but it is hard not to think of that block in Akron as a nexus of fear, dysfunction and unrest. I still consider, from time to time, what artifacts of that Akron turmoil remain in my sinew and blood. But despite the persistent curse, if such exists, many of my cousins and I have learned to both calm and honor our DNA. Many have been very successful, evidence of the remains of overriding Thornton, Youtz, and Vandersall intelligence, resilience and drive.

[blocktext align=”left”]…while imprinted with my parents’ misery in that difficult time, I always felt hope – a hope energized by simmering anger.[/blocktext]Whatever. In 1961 I was a kid, and so, while imprinted with my parents’ misery in that difficult time, I always felt hope – a hope energized by simmering anger. I felt sorry for my parents – a dangerous and sorrowful sympathy – but I loved them fiercely, and in that passionate ambivalence I see now that I began to grow up. I was angry at my father for losing our beautiful life in Canton. I was angry at the conference superintendent who kicked us out. I was angry at the white men who preferred golf to my father’s sermons. I was angry at the big tough girls who mugged me. I was angry at my mother for lying in bed all day. At least my Great-grandfather Youtz did something dramatic, but I was angry at him for possibly passing his madness on to us. I was angry at Akron for being the crucible of all of it: the place where, of course, I began to lose my innocence.

But I had learned to be a nice girl, so, I did my best, as did we all. I was a good girl, striving as hard as I could to make my parents happy. I contained myself. But I had hope – after all, I assumed, I would eventually escape and be myself.

******

At the end of two years my father waved the white flag. His bosses weren’t happy with him anyway. They sent us to another planet: rural Coshocton County, where we lived in a creaky parsonage in a tiny town mis-named Blissfield and where my parents’ unhappiness took on a different dimension. But my mother could forget about her ancestors and found a great and consoling friend in an old woman next door. My father pluckily navigated among four small churches on a white motorscooter, undoubtedly relieved that at least nobody wanted to play golf. For me, the new parish was another adventure and I assumed, as usual, that eventually I could choose my own escapades and set myself apart from my parents’ griefs.

But hardbitten Akron stayed with us all, a nettling bitter memory.

******

Years later, I heard that Akron Calvary Church burned down. I did not contain myself.

Front page of the church denominational newsletter after Calvary Church burned down. Courtesy of the archives of Ohio United Methodism, Ohio Wesleyan University, used by permission of the Ohio East Area of The United Methodist Church.

“Good riddance,” I bellowed to everyone and no one in particular. Of course it wasn’t the building’s fault, but its dramatic ending fit my freighted memories. I dug into the story: an archivist from the United Methodist Church – the denomination the Evangelical United Brethren eventually joined – confirmed the structure burned down July 13, 1971. All 25 children in a Model Cities Day Care Center in the church were led to safety. Akron Calvary, at last, had been doing good things for the community before the fire took it down. The parsonage next door was saved, but the church itself was ruined beyond repair. Outside the church, however, a large bulletin board remained. On it, the pastor, Rev. Bob Hahn, loaded this message, apparently for the arsonist accused of setting the blaze: “You think this fire was hot.”

******

For a time, I heard, the parsonage was a home for unwed mothers. Eventually all was torn down, including Thornton Junior High School, and I understand an Aldi’s sits there now. On Google, I see there IS a house at the parsonage address – but it is a new one, unrecognizable and disorienting to me. My parents have been dead for 20 years. And long gone is 793 Coburn Street.

I wonder if some of the ghosts that haunted that place so many years ago still whisper and waft in the air. If so, one of those ghosts might be the young me, learning none too soon that fathers can fail, that mothers can be wounded with loneliness, that the ancestors are not gods, that the world is full of struggle, and yet that all of us can begin to seem, in all our lostness, even in Akron, Ohio, poignantly noble.

___

[1] Akron Beacon Journal, 12 Sept 1904, p. 1.

[2] Akron Beacon Journal, 3 Dec 1935.

[3] “Workers Lead Children Safely from Church Fire.” Ohio East Area News: United Methodist Church. Vol. VIII, No. 6: September 1971.

Banner photo: Youtz daughters with their children on the porch steps at 793 Coburn Street. My mother, Carol, is the little girl in the middle front, my grandmother Amy at the left holding the baby. Courtesy of the personal archives of Jan Worth-Nelson.

Jan Worth-Nelson is retired from 25 years as a writing teacher at the University of Michigan – Flint. An Ohio native, she graduated as a journalism major from Kent State University. She is editor of East Village Magazine, a long-running community journalism publication in Flint, where residents still are drinking bottled water. Author of the Peace Corps novel Night Blind, Worth-Nelson has had recent work in Midwestern Gothic, the McGuffin, Exposition Review, and forthcoming in Hypertext Magazine and Rhino. Her essay “Beam, Arch, Pillar, Porch: A Love Story” appeared in Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology published in the summer of 2016 by Belt.

Hello, Janice,

I am Ahmed Tahir.

I enjoyed reading your story and would love to hear from you.

Perhaps you remember me from Calvary EUB.

Just found you by accident looking for EUB in Akron.

I left Akron in 1967. I live in NY.

OK That’s it. If you want more, write!

Ahmed