On Black and White Indiana During the Great Migration

By Jennifer Sdunzik

The following is adapted from The Geography of Hate: The Great Migration in Small Town America by Jennifer Sdunzik. Copyright 2023 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

The beginning of the twentieth century marks a time when many southern Black people started to contemplate alternatives to sharecropping by moving out of the South, sparking what is commonly known as the Great Migration. The Great Migration recorded previously unseen population shifts in the United States—and Indiana was no exception. While most migrants landed in big cities, southern Black migrants did have a desire to settle in the Promised Land of the North. Black migrants did not only pass through the state of Indiana, the self-designated crossroads of America, but also acted on their desires for land ownership, better education, and adequate pay and settled in the state. But the narrative about the Great Migration as we know it does not fit Black migrants’ experiences in small-town Indiana.

African Americans lived in small-town Indiana, yet we barely know anything about their destinies in these locales. Over the Great Migration decades (1910-1970) alone, the state’s Black population more than quintupled (from 60,320 in 1910 to 357,464 in 1970) while the total population almost doubled (from around 2.7 million in 1910 to close to 5.2 million in 1970). Indiana’s Black population was rising particularly during the second wave of the Great Migration (1940–1970).

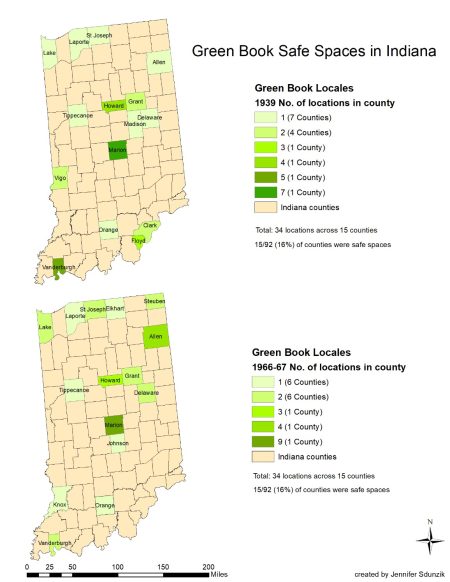

The second wave of the Great Migration also coincided with the publication of the Negro Motorist Green Book, commonly known as the Green Book. Starting in 1936 and continuing for the next three decades, the Green Book listed establishments, including restaurants, hotels, and gas stations, that catered to Black customers, to facilitate road travel for Black travelers in the continental United States. Indiana establishments first appeared in the guide in 1939 and continued to appear until 1966-67, the last edition of the Green Book. Despite the threefold increase in Indiana’s Black population from 1940 to 1970, the total number of individual safe locations and counties remained steady (thirty-four locations across fifteen counties), though we can see a slight shift in where the spots are located (Map 1). Housing the largest Black population in the state, Marion County, with Indianapolis as its county seat, listed the highest number of safe spaces in the state, with seven in 1939 and nine in 1966–67.

Map 1 Green Book locales in Indiana, 1939 and 1966-67

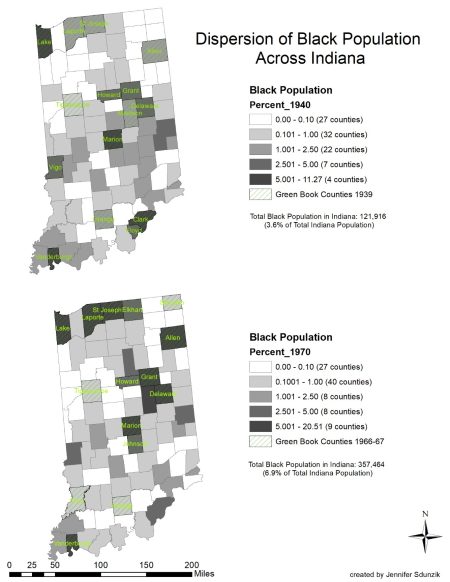

Is there a correlation between the number of Black residents and safe spaces listed in the Green Book? Let’s look at Map 2.

Map 2 Indiana Black population in 1940 and 1970 with identified Green Book counties

At the first glimpse, both maps look quite similar. When we look closer, however, we might notice a few interesting details—despite the unchanged number of Green Book locales. For example, despite an almost threefold increase in its Black population between 1940 and 1970, Indiana has the exact same number of counties with a nonexistent (or almost nonexistent) Black population—twenty-seven counties. Also, there seems to be no obvious correlation between Green Book listings and Black population. Vigo County, in the western part of the state, has a similar percentage of Black residents in both years (4.06 percent in 1940 and 4.7 percent in 1970), yet it no longer has a safe space in 1970. In contrast, Knox County, in the southwestern part of the state, has a similar percentage in both years but added a safe location in 1966–67 (0.59 percent in 1940 and 0.84 percent in 1970). Madison County, in central Indiana, witnessed an increase in its Black population of close to four percent and had a Black population of 5.8 percent of the total county population in 1970, yet unlike in 1939, it no longer included a safe space in 1966–67. As there was no clear correlation between Green Book locales and Black population, it appears I unearthed what historian Anna-Lisa Cox coined the “odd” midwestern racism, which “was not based on numbers and could be touched off by the presence of only one black person, or none at all.” Her observation seems accurate when considering the minuscule Black population (up to 1 percent of the total county population) of two-thirds of Indiana counties in 1970 (sixty-seven counties; see Map 2).

Clinton County and its county seat, Frankfort, the prime locations under investigation in the Geography of Hate, serve as a gateway to understand why so many Indiana counties visibly remained untouched by the rising Black population. Unlike the state at large, Clinton County’s population remained steady over the course of the Great Migration, with a net difference of less than 4,000 inhabitants from 1910 to 1970. While Frankfort grew in size over the course of the Great Migration’s first wave, its total population plateaued in the second wave, with a net difference of 1,250 residents between 1940 and 1970. However, the same cannot be stated for the county’s minuscule Black population, where we observe a stark decline (Figure 1).

Indiana became the crossroads of desires during the Great Migration—where Black Hoosier desires for the pursuit of happiness in the small-town Midwest clashed with white Hoosier desires to keep their communities white. Figure 1 insinuates that African Americans started to abandon the small-town Midwest for other places, though we may not know their final destinations. We do know, however, that Clinton County, like many other Indiana counties, became whiter as the state at large became blacker.

Black southern migrants wanted to settle in the small-town Midwest, and white midwesterners wanted to keep their communities white. How did this dynamic unfold in the national press? A brief discussion of the migration coverage in the national press will elucidate the extent to which small-town America embraced Black or white desires.

Black Newcomers Meet White Midwestern Hostility

The Great Migration mattered in the national press. World War I was frequently identified as the catalyst of the migration stream, as it halted European immigration and increased demand for labor across the country. Articles overwhelmingly discussed the migration’s causes and consequences. Identified causes for the relocation included economic freedom and educational opportunities. Violence through the KKK and lynching, as well as voting and the boll weevil infestation of the cotton crops, were also listed as reasons for leaving the South. As the national press primarily derives from urban areas, it mainly discussed the consequences of the migration as city problems, ranging from job and housing discrimination to health and sanitation issues in the segregated, depleted areas, as well as an increase in violence and crime.

In the context of the Great Migration coverage, small towns are, in most instances, a side note or point of reference in the national press. The small-town nature was mainly attributed to the South, and northern small towns are rarely discussed as a viable option for southern Black migrants’ relocation. Notwithstanding, the articles attest how white Americans displayed a blatant animosity toward the Black newcomers in northern small towns, hinting at why these locales may not have been considered worthwhile among Black migrants. Such maltreatment is generally associated with the traditional South, but these attitudes were present in white minds across the nation and across time.

Once the Great Migration was under way, Black folk struggling to exercise their citizenship rights in the Midwest was a recurring concern in the Chicago Defender, the most prominent Black weekly of the time with national readership. Reflecting deep-seated midwestern discrimination in 1929, the paper reports “[T]hree respectable ladies, not white, of Chicago were refused the use of the comfort station” at a gas station between the Michigan state line and Michigan City, Indiana. As the ladies relieved themselves in the nearby bushes, “the man keeper was objecting to even the car standing there for the very few urgent moments and threatened to charge for parking.” The risk of traveling while Black becomes more obvious later in the article: “This station and succeeding ones in Indiana read, ‘We cater to white trade only.’ This will spread into Michigan and Illinois.” Although the development of the automobile and expansion of highways improved Black people’s spatial mobility, white racist attitudes and violent threats curbed it. For decades throughout the twentieth century, transit through and settlement in midwestern small towns came with great risk for Black migrants.

The documented encounters of Black newcomers in northern small towns across the twentieth century demonstrate persistent white prejudicial attitudes and supremacist ideologies. At times, the national press captured racial animosity in its coverage of outbreaks of racial violence that took place in big cities and small towns alike. And in both scenarios, white desires were at the forefront. For example, in the wake of the East St. Louis riot in 1917, local white residents organized various anti-Black meetings, during which agitated white people circulated the idea that the city “must remain a white man’s town.” By 1917, East St. Louis had a population of more than 60,000. In smaller locales, these outbreaks frequently resulted in “requests” by white residents for Black residents to leave town. Liberal congregational minister Rollin Lynde Hartt discusses four such incidents in a three-part series of articles on the migration mainly dedicated to the causes and impact of the Great Migration. An incident in South Bend, Indiana, resulted in letters being “sent to Negroes ordering them to leave town,” and in an Ohio township, “‘vigilantes’ tried to drive out the Negroes.” In Johnstown, Pennsylvania, the mayor himself expelled 1,200 Black residents. Those expulsions actually became newsworthy on the national stage at times. For example, the New York Times reported “All Negroes Driven from Indiana Town” with the subheading “White Miners at Blanford Act after an Assault on a Young Girl” in 1923. Besides revealing that white midwesterners actively contributed to making their communities all white, articles reporting on these expulsions are also a testament to the existence of Black residents in small-town midwestern America.

Segregation was a reality for Black folk in the North as much as it was in the South. Despite assumptions that the longer the Great Migration went on, the more northern whites would get used to the idea of a Black neighbor, the situation did not improve much for Black newcomers in the Midwest over time, as George S. Schuyler documented in “Jim Crow in the North” in 1949. Schuyler was a self-proclaimed Black conservative, who ventured politically from the socialist to the extreme conservative side throughout his life. But his politics aside, he remained a keen observer of Black life in the North. The article was published in the aftermath of World War II and the Double V campaign, which inspired more and more African Americans to push for recognition and an end to racism at home. “Sett[ing] the record straight,” Schuyler accorded that Black folk were still second-class citizens across the nation and encountered discrimination across the North, “more subtle, not sanctified by state law, but nevertheless almost inescapable.” He acknowledged that discrimination was a reality in urban and rural areas, affecting work, housing, and leisure. He echoed reasons that underline the necessity of the Green Book when he discussed the obstacles Black travelers needed to overcome to find a hotel or a restaurant in the North, observing, “In about half the cities of the North, Negroes are never accepted. In the others they are accepted but made to feel that they are unwelcome.” He drove his point home by noting that sixteen of the twenty-nine states with anti-miscegenation laws are located outside of the South, uncovering that the “most savage penalties, as a matter of fact, are in the North.” Hospital and cemetery segregation (including dog cemeteries) built the culmination of his argument that Jim Crow ruled the North just like it did the South.

Housing and the consequent breach into white neighborhoods dominated the news in the 1950s and thus constitute an ideal lens into the minds of white northerners. Southern migrants soon realized that people “talk integration [but] act segregation” in the North, and restrictive covenants became the “great weapon of the segregator” in 1954. “Race Trouble in the North: When a Negro Family Moved into a White Community” describes the race troubles in Levittown, Pennsylvania, in 1957, the year when the first Black family moved into town. The article describes Levittown as a “normally peaceful Northern community”—a common description for many midwestern small towns (then and now). Peaceful—until their livelihoods seemingly were threatened by Black newcomers. But it was not the Black newcomers who threw stones and assaulted police, but those very “peaceful” residents of the town. White resident voices quoted in the article reflect their entitlement to claim the neighborhood as theirs, reflecting the hypocrisy of northern whites who claim they did not mind equal rights for Black folk until they move next door. The article uncovers another interesting conundrum. Even though the Myers family was the first Black family moving to Levittown in 1957, all five swimming pools in town already barred Black folk from using them. One wonders how such policy could have been in place already, even before African Americans first attempted to settle there. Unless they were not the first.

Contemporary observers of the Great Migration frequently captured northern white attitudes and opposition to Black people attempting to settle in their white towns, as experienced in Levittown. They described the paradox as the fact that the North loves the race but hates the individual Black person, whereas the South hates the race but loves the individual Black person. It is this paradox that explains that the South is seemingly more integrated than the North. The article “South in the North” juxtaposes the level of prejudice in the North and South via two small-town communities in Illinois and Tennessee, respectively:

There are several ironies in this tale of two cities—one being that Clinton, in the South, with most of its citizens admitting they do not believe in or want integration, is nevertheless partially integrated, while Deerfield, in the North, with the majority of its citizens assuring the world they believe in integration, is nevertheless totally segregated.

The author identifies housing discrimination as a “key to northern segregation” and as one of the crucial mechanisms to prove white superiority, elaborating: “Symbols of that superiority differ. In the South they include separate school and lunch counters. In the North, the symbols of status are houses, the pecking order of suburban communities. Superiority here may be established by a man’s address.” Invisible to the eye but far from race-neutral, white supremacy is embedded in these spaces—through attitudes and policies that represent white values and predetermine white wealth.

The strict enforcement of vagrancy and trespassing ordinances, for example, became a popular means in Frankfort, Indiana, to control access to the city and mark Blackness the longer the Great Migration went on. Frankfort was, in fact, a destination for southern Black migrants. Whereas the early-twentieth-century arrivals were not newsworthy, the local newspaper captured the arrivals of Black migrants mid-century, as they were arrested on trumped-up charges. Such coverage not only marked Blackness but also reinforced the stereotype of Black criminality: why else would they break the law and get arrested? Note the consistency in referring to the Black newcomers as “transient.” For example, in early 1942, “Negro Transient” Bennie Rogers was taken into custody because he “had violated a federal code by leaving his home in Gretna, Louisiana, without notifying his local draft board.” Three weeks later, Virgil C. Hamilton, another Black migrant—this time from Lexington, Kentucky—was detained for “trespassing on railroad property.” Arriving via train in Frankfort in 1949, “Negro Transient” Essec Ree Walker, from Magnolia, Arkansas, was hurt “stepp[ing] off a moving boxcar and crash[ing] into a signal standard.” Two other migrants were facing “charges of riding unlawfully in a moving freight train.” If the word spread, the number of arrests might have been a deterring factor for Black migrants not to settle in Frankfort any longer. The word was definitely spread as a strategy to discourage Black people from settling in Frankfort, as the paper reported three days after their arrest that “The fine and costs were suspended on condition the two leave town immediately.” Many migrants did not have a penny upon arriving in the North. Since the two were arrested before securing employment, it was probably easiest to comply with the request to leave town.

Despite the fair share of “negro transients” who “disrupted” Frankfort tranquility, the local paper never contextualized them within the larger ongoing Great Migration. When it covered the Migration’s effects on northern communities, it couched its coverage in general national terms, again conveying the impression that the Great Migration does not concern the local small-town community. After all, the few migrants who did arrive had been taken care of by the laws designed and enforced to protect their ideal white world. However, we can draw a few parallels from said coverage. For example, the Morning Times printed “Problem of Race Relations Not Confined to South; Discrimination in North, Too” in 1956. Besides identifying housing as the major issue of racial tension, the reporter acknowledges the existence of sundown towns in the Midwest, noting that “There are cities such as Cicero, Ill., adjacent to Chicago, and Dearborn, Mich., next to Detroit, which exclude Negro residents through community pressures” and adding that “you can find instances in the North of mob action when a Negro family moves into an all-white neighborhood.” “Community pressures” served as an extralegal, unofficial tool to preserve all-white communities without admitting racist intentions.

Black migrants did arrive in the small-town Midwest. In their chosen new environments, they were met with white hostility—open and outward as well as subtle and hidden. While such white hostility did not prevent them from migrating, it might explain the less dispersed settlement of Black folk across the Midwest. How many Black migrants attempted initial settlements in the smaller towns of the Midwest during the seven decades of the Great Migration, we might never know. Regardless, it is important to note the overwhelming obstacles and animosity they faced when doing so. The sole narrative that the Great Migration involved Black migrants settling exclusively in the urban North obscured Black experiences in the small-town Midwest. For far too long, these formerly all-white communities across the Midwest have been excused and exculpated for their active contribution to creating urban “ghettos.” For far too long, white small-town midwesterners have been acquitted of playing any role in the below-standard accommodations in the segregated areas and the violent unrest erupting in urban spaces for equal rights and equal treatment of Black people. I unearthed some of the hidden legacy of exclusionary policies and attitudes of the American Midwest that kept the region overwhelmingly white for decades during a time when the nation experienced a major demographic shift. This is how the Great Migration became a socially engineered urban phenomenon.

Jennifer Sdunzik is a postdoctoral research associate at the Evaluation and Learning Research Center at Purdue University.