By Bob Zeni

I.

“It’s a place that doesn’t belong to me, but feels like mine.”

—Susan Orlean, The Library Book

In 1917, my grandfather immigrated to America from northern Italy, where he had worked in a coal mine. He lived in Elkins, West Virginia for a few years, working in a coal mine before moving to Decatur, Illinois—where he worked in a coal mine. I never knew him. He died of Black Lung at twenty-eight. My father, whose formal education ended at sixth grade, worked in a steel fabrication plant during Decatur’s era of peak industrial strength, the 1950s and 1960s. In those years, when I was in grade school, he repeatedly tapped my temple and told me: “You’re going to make your living with this, not this” before grabbing my shoulder. To that end, he made sure I spent Saturday afternoons in the Decatur Public Library, a center of civic life endowed by Andrew Carnegie.

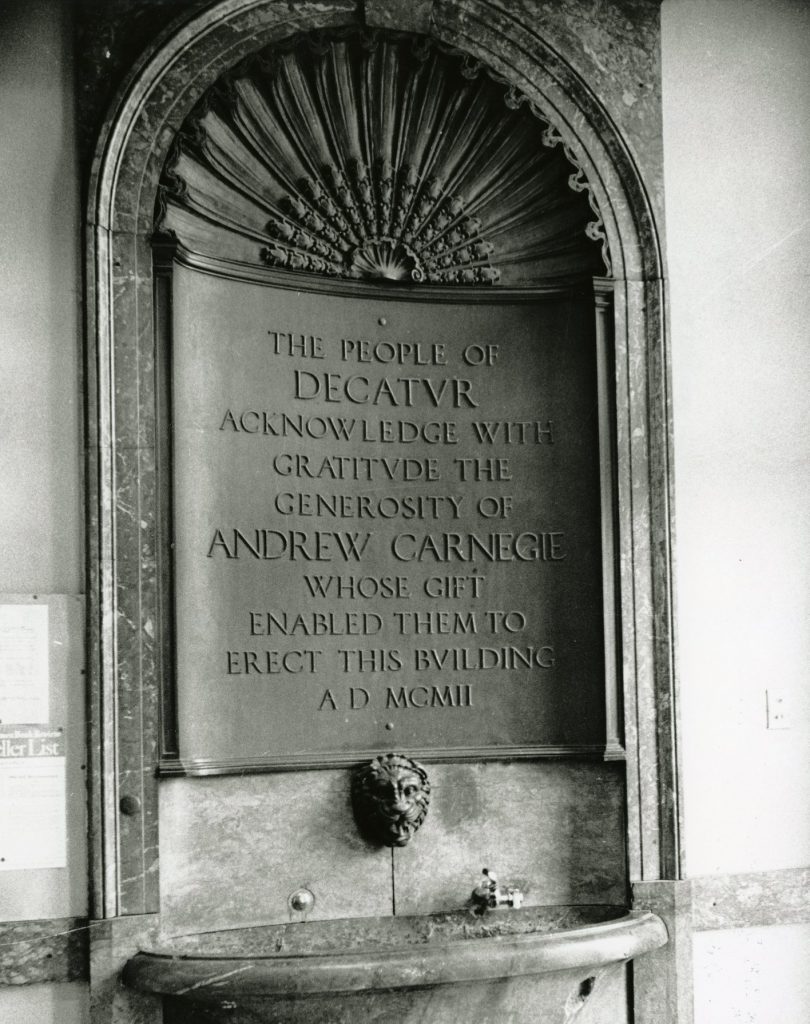

There was nothing like it: massive, stolid, imposing, the heart of downtown. Like many Carnegie libraries, the Decatur Public Library was built above grade. A lamppost out front symbolized enlightenment. Wide stairs, leading up from the sidewalk, were meant to elevate you to learning and encourage you to quiet your mind (and mouth). In the foyer, above a drinking fountain on the north wall, an impressive four-foot square, cast-bronze plaque read: THE PEOPLE OF DECATUR ACKNOWLEDGE WITH GRATITUDE THE GENEROSITY OF ANDREW CARNEGIE WHOSE GIFT ENABLED THEM TO ERECT THIS BUILDING.

Carnegie’s gifts, each up to $10,000 (in 1910 dollars), helped build more than three thousand libraries worldwide. Seventeen hundred of them were in the United States, with many in the Midwest: 165 in Indiana, 106 in Illinois, 106 in Ohio, 101 in Iowa and sixty each in Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Carnegie’s money promoted a public/private partnership. Towns needed to demonstrate the need for a public library, provide the building site, and draw from public funds (not just private donations) for operations and maintenance. Each library had to provide free service and use the then-radical notion of self-service stacks.

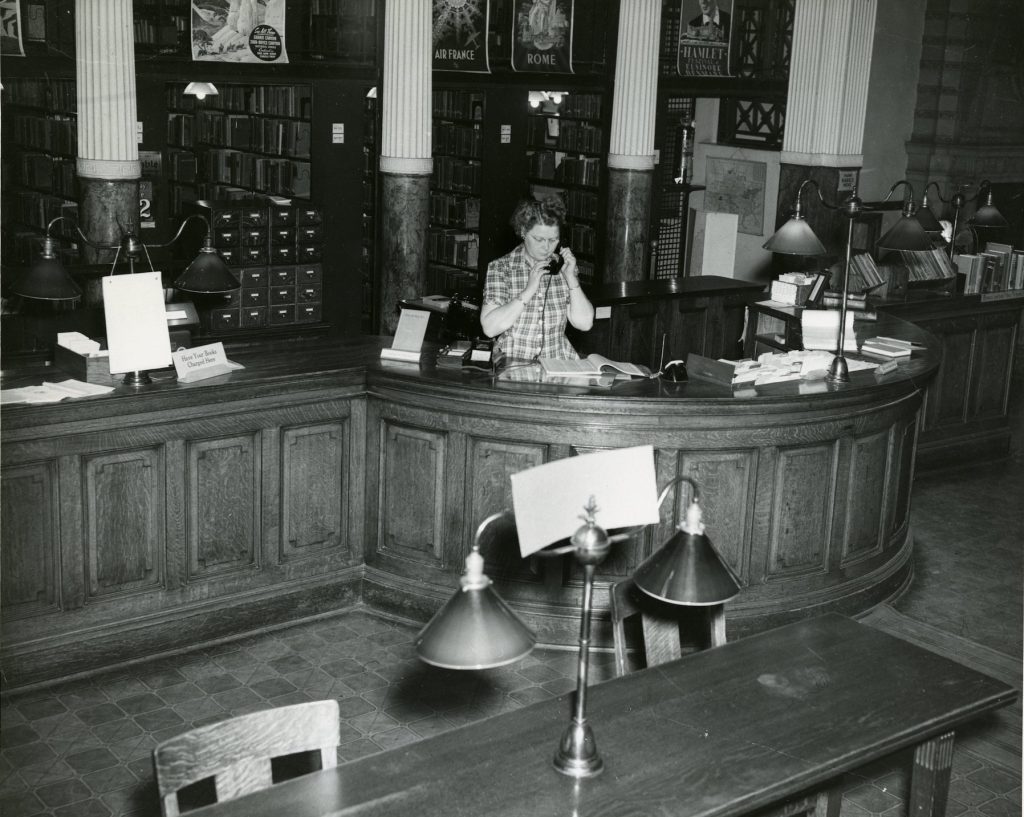

The Decatur Public Library opened on July 3, 1903. Filigreed wrought iron formed the balusters and banisters of the spiral staircases. The floors of the stacks were smoked glass block. Heavy wooden tables waited in rows in the reading room. The battleship circulation desk, anchored beside the exit, was manned by an all-woman crew of librarians.

As the library thrived, the town prospered. By mid-century, Decatur had a robust downtown, a high-quality school system, a park within a short walk of every home, and, seemingly, a job for every man willing to work. Factories flourished—Borg-Warner, Burks Pumps, Cash Valve, Caterpillar, Essex Wire, Firestone Tire, Marvel-Schebler, Mueller Iron Foundry, Mississippi Valley Structural Steel and Wagner Castings. Surrounded by the most fertile soil on the planet, Decatur was – as the sign on Route 36 proclaimed – “Soybean Capital of the World!” It was home to processors Archer Daniels Midland and the A.E. Staley company, which became synonymous with the city. Staley’s headquarters was the tallest building in town—twelve stories topped by a lit cupola. Dad told me Santa Claus stayed there when he was on vacation from the North Pole. Staley’s company football team, the Starchworkers, evolved into the Chicago Bears and gave birth to the National Football League.

By my time, the library was showing its age. The steps were rutted. The marble floors cracked. The aroma slightly musty. The patina on the iron rubbed away by countless hands. I noticed the wear and tear, but didn’t care. It wasn’t home or school. At the library, I discovered I wasn’t alone. I met kids from other neighborhoods. Guys who preferred reading over football. Girls who, like me, puzzled over Wrinkle in Time. Sometimes I simply roamed the stacks. All that knowledge right there, waiting for me. The first time I checked out a book alone – in fourth grade – I ran to the car, nervous and sweating. “Quick, Mom. Get outta here,” I thought. “They might arrest me!” Returning it a week later, I was so proud. I’d stolen the book’s contents without paying. I was an outlaw.

In junior high, I spent Friday nights at Teen Town, a dance at the YWCA, which stood directly across the street (or “acrost,” in Decatur lingo) from the library. As a high school freshman, Friday nights meant dances at Fun Club at the YMCA, three blocks south. The older kids with licenses and access to their parents’ cars idled away the evenings cruising Eldorado (“Eldo-RAY-do”). The two-mile circuit ran alongside the library, from McDonald’s to Sandy’s, an unabashed central Illinois knockoff of McDonald’s, which sat catty corner from the campus of Millikin University. In between, drivers would stop at the Steak ’n Shake for an orange milk shake delivered by waitresses on roller skates. Or pull into Elam’s for the deep fried pork tenderloin and a mug of Silverfross root beer.

Stephen Decatur, for decades the town’s only high school, was located downtown, three blocks east of the library. In the 1960s, its gym regularly hosted the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars, a rare chance to see the pop stars we’d heard on WLS Chicago. Black kids and white kids alike attended without incident. Big families – four children were customary and a brood of nine or ten was not uncommon – wove tapestries of kinships that blanketed Decatur. Despite having a population of eighty thousand in 1970, it felt like a small town. Everyone seemed to know everybody. Gee willikers, so Pleasantville or American Graffiti!

Don’t get carried away. Pre-EPA, soybean processing belched particulates acidic enough to pockmark your car. Its intense stench assaulted the senses, often becoming visitors’ singular memory of Decatur. And industrial waste? Oh, just throw it anywhere. When I was ten, playing in a wooded ravine behind our house, I gashed my left palm down to the bone. Some company had randomly dumped dozens of half-broken, oven-size glass castings. Dad cinched my hand together with duct tape on the way to the hospital to stanch the gushing blood.

II.

“The decade following World War II represented the high-water mark of civic life in modern America. As the U.S. disinvested in the infrastructure and even the idea of the commons, the vital center frayed. Cities thinned out in the center and thickened on the edges.”

—Jane Kamensky, director of Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America

On July 25, 1972, Decatur ripped out its heart when it demolished the Carnegie Library. “The library was in need of a larger facility,” reads the clinical description on the current Library website. According to a 1996 survey, less than fifteen percent of the original Carnegie library buildings in the U.S. have been torn down. Many have been converted to shops, condos or community centers. Nine hundred remain libraries. Of them, 276 are unchanged, 175 have been remodeled and 286 have been expanded.

Beginning in the late 1960s, a plague of mall fever swept central Illinois – Eastland Mall opened in Bloomington in 1966, Northwoods in Peoria in 1973, Market Place in Champaign in 1975 and White Oaks in Springfield in 1977. Decatur, however, did not succumb. On July 8, 1974, the City Council, under the pressure from downtown retailers, demonstrated the obstinate pride and the mulish defiance endemic to Decatur by rejecting a proposal to annex property north of town for a mall. One month later Forsyth, a flyspeck of six hundred people just north of town, approved a nearly identical proposal. The Hickory Point Mall, opened in 1978, anchored by J.C. Penney and Sears, which abandoned their downtown locations.

Stephen Decatur High fell next. A 1973 fire caused minor damage. A study ruled out renovation. It recommended, instead, a new school on the north edge of town. In 1975, the building was demolished. With it went foot traffic for downtown businesses. A photo in the Decatur Herald & Review at the time shows people strolling sidewalks downtown. The caption quotes a downtown retailer: “I’m sick and tired of hearing doom-and-gloom stories about the Hickory Point Mall destroying the retail trade in downtown. I welcome the mall,” the merchant said. “We will coexist. One of the first things I learned in retailing is that competition is good.”

Oops. By 1980, Forsyth’s sales taxes soared to $500,000 per year, from $6,000 six years prior. “We’ve been paying the price ever since (that vote),” said former Decatur Mayor Terry Howley, in a 2002 story in the Herald & Review. “There was a lot of foresight in Forsyth at that time and very little south of the border.” Another former mayor, Paul Osborne, called it “The worst decision ever made.”

In place of the high school, Decatur built a civic center. It offered programs and activities…which never caught on among youngsters or teens. The Soy Capital Bank – where I opened my first Christmas Club savings account – moved from its location near the McDonald’s to the site once occupied by the Carnegie library. The property was graded down to street level for easy access to ATMs.

The library’s contents were moved to a former Sears store. No lamppost for enlightenment, no stairs to evoke inspiration. On Christmas break from college in 1973, I stopped in. No wood, no marble, no filigreed wrought iron. Just an expanse of carpeting, cubicles and conference tables – all in shades of beige – under Armstrong drop ceilings. Granted, it was the holidays, but I was nearly alone. I crammed for finals with my head down. Left with a sense of loss.

I didn’t return to Decatur much after graduating from college. Maybe for a reunion or birthday party. Once every five years or so. At each visit, the anxiety of friends and family was more palpable. Decatur’s distress more obvious as intense and enduring labor battles tore apart the fabric of the community. (For a detailed description, see “The Decline of Decatur,” by Roger Biles in the Journal of the Illinois Historical Society, Summer 2017,)

Population dwindled to seventy-five thousand by 2015 from a peak at ninety-five thousand in 1980. Forsyth’s jumped to nearly six thousand residents. Mt. Zion, just south of town, more than doubled to 5,888 from 2,343 in 1970. Many young adults moved out of the area entirely. Downtown became increasingly spectral. Shops that had thrived for decades vanished. My favorite haunts – Hobby House, Spin Shop and Haines & Essick – among them. The St. Nicholas, Orlando and Ambassador Hotels checked out, leaving downtown bereft of lodging for visitors.

Entire buildings disappeared, replaced by piles of rubble or parking garages accessible only by card keys. Others were partially torn down, as if a gangrenous appendage was lopped off, leaving the interior walls facing empty lots, third-story hallway doors exposed like cauterized arteries. The entire area seemed disjointed, incapacitated, the sum of its parts less than a whole. I stopped going downtown at all.

III.

“Third places are the public places on neutral ground where people can gather and interact. They provide the foundation for a functioning democracy…offering psychological support to individuals and communities.”

—Ray Oldenburg The Great Good Place

In 2015, a high school class reunion at a restaurant downtown lured me back. I parked in front of Soy Capital, used its ATM, and marveled as I looked down Main Street. Anna Thai, Bizou, Sol Bistro, the Downtown Café and Coney McKane’s now formed a restaurant row between William and Prairie. Nail salons and hairdressers had nestled nearby. Not typical central city commercial dynamos. But even these – maybe especially these – offered camaraderie and conversation.

Late last year, I returned, determined to view the town with fresh eyes. I stopped into the ArtFarm, a gallery where my cousin Duggie, a former tradesman turned wood artist, displays his work. It opened in January 2018. “There’s a generation people in their mid ’60s who have this constant buzz of ‘Decatur was once so great.’ ‘Decatur ain’t what it used to be.’ ‘Everything sucks now,’” said Peggy Baity, the owner of the ArtFarm, who offers a cup of tea. “I’m the kind of person who believes that if you bitch about it, you better be able to do a better job. I caught myself bitching an awful lot. And I thought, ‘Well, you know what, I’m just going to take care of this myself.’…“That’s a trait of people who grew up around here. That’s the roots in our union, blue-collar, grinding-it-out upbringing. ‘If I don’t make this happen, nobody else is going to.’”

Later, I walked over to the library – the new new one, having moved in 1999 from the 1930s Sears store space in the northeast corner of downtown to the vacant 1966 Sears space in the southeast corner. The décor is colorful, tasteful and lively, dotted with displays and kiosks. To the left, a dozen patrons are using computer screens. Most are elderly. Another dozen people of all ages are scanning the stacks, which reach back into the far corner. Beyond glass doors trimmed in wood, a collection of historical documents are housed in its own room.

“I grew up about an hour southwest of here,” Rick Meyer, Decatur’s head librarian, who was hired in 2014, told me. “Probably a quarter of my friends’ dads worked here. Decatur had a reputation: ‘Dangerous.’ ‘It doesn’t smell good.’…What I found is that this city is not what people think it is. I’ve found people committed to their community. Great volunteerism in this town. We have problems and challenges, but it’s much better than expected.” Meyer and his staff are working closely with the city government and other agencies to address Decatur’s issues—hiring local people, as well as hosting literacy programming and community town hall sessions.

Will all this translate into a downtown – and a city – that’s robust and thriving? I don’t know. Maybe. Hopefully. But as I left the library, I did I notice something familiar, something I missed on the way in. There, mounted in a custom alcove beside the entrance, was a large, thick, cast-bronze plaque. It’s the original, bent on one side, but cleaned and polished, perhaps recovered from the debris of Decatur’s first monumental library building. Of course, it still read: THE PEOPLE OF DECATUR ACKNOWLEDGE WITH GRATITUDE… ■

Bob Zeni is a writer, editor, and designer in Chicago.

Cover image of a postcard featuring the Decatur Public Library’s Carnegie facility (digitally enhanced). Image courtesy Decatur Public Library.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.