That the building has endured is, in its own small way, a testament to Ebony’s lasting legacy, Chicago’s rich Black business and literary history, and the continued tenacity of Washington Park’s residents.

By E. James West

On the west side of Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood, on the right of South State between 56th and 57th Street, there are only two buildings left.

The first building, located at 5625 South State Street, is typical of the one and two-story commercial storefront buildings that sprung up along Washington Park’s main thoroughfares and streetcar lines during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. At least initially, these sites were occupied by businesses that catered to affluent whites (attracted by its the neighborhood’s proximity to one of the city’s premier green spaces) and working-class Irish and central European migrants (by its proximity to the railroad and meatpacking districts). However, by the third decade of the twentieth century, the onset of the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South had begun to reshape Washington Park and other Chicago neighborhoods. 5625 South State’s most recent occupant, the 2nd Timothy Missionary Baptist Church, was one of the many Black storefront churches dotted across the city. The black letters on the whitewashed shutters of its front façade are faded and peeling. You can still make out words from the bible verse that gave the church its name: “study to show thyself approved unto God.”

The second building, at 5619 South State Street, is in a similar state of disrepair. Its shutters are rusty and marked with graffiti. Its brickwork is faded and cracked. There’s no visible sign to mark its significance as the birthplace of the most successful Black periodical in American history.

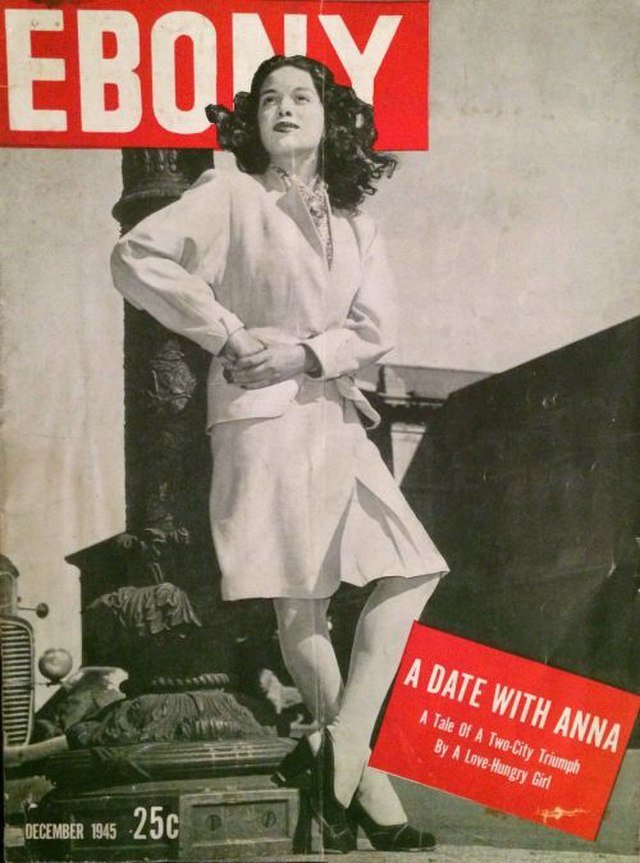

It was here, in November 1945, that John H. Johnson founded Ebony, a glossy photo-editorial magazine marketed as a Black equivalent to Life. Almost overnight, Ebony became “the largest Negro magazine in the world in both size and circulation.” It was first Black publication to crack the color line with major corporate advertisers. Ebony’s monthly circulation eventually grew to more than two million, with the magazine claiming that its pass-on readership saw it reach “more than half of all Black American adults.” This extraordinary popularity underpinned Ebony’s relocation from 5619 South State to increasingly larger offices, culminating in a custom-built corporate headquarters on the South Loop. By the 1980s, Ebony’s success had elevated Johnson Publishing Company to a position as the nation’s premier Black business.

5619 South State Street is an ordinary building that housed an extraordinary story. That Ebony was founded here reflects the transformative impact of demographic change in Washington Park during the first half of the twentieth century, the neighborhood’s importance as a Black Mecca, and the indelible relationship between Johnson Publishing and Black Chicago. That it now stands forgotten on a largely vacant block is indicative of similarly dramatic economic, demographic, and political shifts that have reshaped Washington Park and contributed to the decline of Johnson Publishing. That the building has endured is, in its own small way, a testament to Ebony’s lasting legacy, Chicago’s rich Black business and literary history, and the continued tenacity of Washington Park’s residents.

*

Chicago, like all great cities, is a city of neighborhoods. Here, the process of neighborhood formalization occurred during the 1920s, when a team of University of Chicago sociologists headed by Robert E. Park and Ernest Burgess organized the city’s many wards, political subdivisions, and neighborhoods into 75 distinct “community areas.” Washington Park is the fortieth of these areas. Stretching from 51st Street to 60th Street, the neighborhood is roughly square-shaped, although its bottom left-hand section juts a little further south to connect with the King Drive “L” Station on 63rd Street. From this station, passengers can get a good view of Chicago’s downtown, located around seven miles due north. To the West, its official border is the Chicago, Rock, Island and Pacific Railroad, and its unofficial border is the Dan Ryan Expressway, an imposing asphalt barrier that splits South Chicago in two. To the East, Washington Park ends at Cottage Grove Avenue, which also marks the easternly border of the park that gives the neighborhood its name. Dedicated in 1879 by ex-president Ulysses Grant, Washington Park is a crown jewel within Chicago’s public parks system; a sprawling, 372-acre green space that encompasses the entirety of the neighborhood’s eastern section and some forty percent of its total area.

Washington Park’s residential and commercial buildings are clustered in the neighborhood’s western section. Described as “taxpayer blocks,” one and two-story commercial storefronts such as 5619 South State were designed to provide new business opportunities and rental income for property owners eager to participate in Chicago’s demographic and economic boom. At least initially, these buildings were predominantly occupied by the families and businesses of ethnic European immigrants, drawn to Washington Park by its proximity to Chicago’s stockyards and railroad hubs. Larger residences and upscale apartment buildings, clustered along prominent boulevards such as State Street and South Park Avenue (now King Drive), were reserved for wealthy white homeowners, who coveted access to one of the city’s premier leisure spaces.

However, World War I heralded the onset of the Great Migration, a mass movement of African Americans out of the South and into northern cities such as New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago. This influx of Black migrants boosted the profile of Black entrepreneurs such as Robert Abbott, the publisher of the Chicago Defender, and Jesse Binga, one of the city’s most influential Black realtors and power brokers. Binga pioneered the practice of “Blockbusting,” which involved purchasing or leasing properties in predominantly white areas, and then taking advantage of the subsequent exodus of white residents to buy up cheap property that he could then rent or resell to Black clients. In 1917, Binga purchased a home at 5922 South Park Avenue in what remained an exclusively white enclave towards the lower end of Washington Park. Binga’s home was bombed multiple times; a product of racist white backlash that arguably culminated in the devastating race riots of 1919, when the years-long build-up of racial tensions and animosities “explode[d] in bloody warfare.”

Racial resentments continued to fester, but continued Black migration meant that Washington Park’s status as a “white island” was living on borrowed time. In 1920, Washington Park had a population of around 38,000, with Black residents constituting just fifteen percent of this total. Ten years later, the neighborhood’s population had marginally increased to 44,000, but more than ninety percent of its population was Black. With startling rapidity, Washington Park was incorporated into the South Side’s expanding “Black Metropolis.” The majority of new residents crowded into tiny kitchenettes created by the partitioning of more spacious apartment buildings that had been abandoned by white patrons.

At the same time, Black community groups, religious organizations, and leisure locales eagerly seized control of spaces vacated by white enterprises. This included the B’Nai Sholom Temple at 5301 South Michigan Avenue, which was transformed into Greater Bethesda Baptist Church during the mid-1920s, and St. Anselm’s church at 6045 South Michigan Avenue, whose Irish Catholic congregation was replaced by Black parishioners during the same period. Black businesses also moved in. During the 1920s and early 1930s, 5619 South State Street was occupied by De Moe Engineering Laboratories, a manufacturing company headed by white suburbanite Earl T. De Moe. By the end of the decade, it had become the headquarters of the National News Company, a Black-owned news agency owned by brothers Carroll and Raymond Ellis.

*

Among the many Black Southerners to make their way to Chicago during this period was Arkansas native John H. Johnson, who relocated to the Windy City with his mother during the 1930s. After graduating from DuSable High School, located at 49th Street and Wabash Avenue, Johnson joined Supreme Life, one of the nation’s largest Black-owned insurance companies. As an assistant to company president Harry Pace, Johnson was entrusted with compiling a weekly digest of Black news, and the enterprising young employee quickly realized he had stumbled across a potential goldmine. Using the Supreme Life address rolls, Johnson solicited advance subscriptions for a monthly newsmagazine that he pitched as a Black counterpart to Readers Digest. The appropriately titled Negro Digest began publication out of the Supreme Life building at 3501 South Parkway in November 1942.

Within a year, the magazine’s circulation had breached 100,000, providing Johnson with the necessary capital to relocate his budding print enterprise from the Supreme Life building to its own headquarters at 5619 South State Street, which he purchased from the National News Company for $4,000. Johnson described the building as “a typical Chicago storefront with a big plate-glass window facing the sidewalk.” The publisher also purchased a three-story apartment building at 6018 St. Lawrence in the exclusive Washington Park subdivision located below the park’s southern border. In a city characterized by redlining and systemic housing segregation, these purchases were their own small protest – a reminder that despite its challenges, Black businesses and Black people could thrive in Chicago.

Johnson’s personal and professional relocation was indicative of the broader movement of many Black Chicagoans during the 1930s and 1940s. During and immediately after World War I, the heart of Chicago’s Black community was centered along the 35th Street Corridor, close to landmarks such as the Defender building at 3435 South Indiana and the Sunset Café at 315 East 35th Street. Known as “The Stroll,” this vibrant Black entertainment and commercial district was breathlessly described by poet Langston Hughes in 1918 as “a teeming Negro street with crowded theaters, restaurants, and cabarets [and] excitement from noon to noon.” However, as Black Chicago continued to grow, its focal point shifted southwards towards and then beyond 47th Street, drawing Washington Park closer to the center of the city’s burgeoning “Black Metropolis.”

Perhaps the most dramatic example of this communal transition was the redevelopment of the sprawling Chicago Orphanage Asylum site at 5125 South Park Avenue into Parkway Community House. Historian Lawrence Jackson describes Parkway House as a “major outreach center devoted to improving the social, educational, and recreational lives” of Black South Side residents, and the site served as an incubator for an outpouring of cultural and artistic expression during the 1930s and 1940s that would come to be known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. Other local hotspots included the Rhumboogie Club, which was located at 55th Street and Garfield and backed by Black heavyweight champion Joe Louis.

Energized by his proximity to such locales, Johnson poured the revenues generated by the success of Negro Digest into an altogether more ambitious project. In November 1945, he launched Ebony, a glossy photo-editorial magazine designed as a Black counterpart to Life. Almost overnight, Ebony became “the largest Negro magazine in the world in both size and circulation,” with an initial press run of 25,000 rising to nearly a third-of-a-million by its fourth issue. Johnson informed readers that this unprecedented growth necessitated a change in address: “Ebony has outgrown its diapers and will have to get a new home…where it will be able to grow comfortably.” The company leased a two-story building at 5125 South Calumet Avenue from Parkway Community House, where it moved the editorial, circulation, and business departments. Johnson retained control of 5619 South State, which became the center of its warehousing and shipping operations. For the next few years, the nation’s largest Black publishing enterprise had two separate offices in Washington Park.

However, this relationship was not destined to last. While Johnson initially embraced his Washington Park locations and linked the content and character of his publications to the neighborhood which produced them, this soured after his efforts to renegotiate the lease at 5125 South Calumet stalled. At the same time, Johnson sensed a shift towards neighborhood decline and believed that the future growth of his publishing empire was predicated on a move outside of the Black Belt: “South State Street was a back street. Calumet Avenue was a back street. I wanted to work on a front street.” In 1949, Johnson Publishing Company purchased a funeral home at 1820 South Michigan Avenue, only eighteen blocks from the center of the Loop. A few years later, Johnson moved his family from St. Lawrence Avenue to an imposing townhouse on East Drexel Square, still close to the northeast corner of Washington Park but now situated in the adjacent, upwardly mobile, and more racially integrated community of Hyde Park.

*

Johnson’s retreat from Washington Park can be mapped onto the neighborhood’s demographic, economic, and cultural decline. After peaking at nearly 59,000 in 1950, its population dropped to less than 44,000 in 1960. This drop was at least in part the result of postwar redevelopment programs accelerated by the passage of the 1947 Illinois Blighted Areas Redevelopment Act, which provided the city government with considerable power to acquire and raze “blighted” buildings through the Land Clearance Commission. In neighborhoods such as Douglas, Grand Boulevard, and Washington Park, Black residents were disproportionately displaced by urban renewal projects, leading civil rights organizations such as the Urban League to decry “urban renewal” as little more than “Negro removal.” Among the many buildings to be torn down during the decades following World War II was Ebony’s former offices at 5125 South Calumet Avenue, which were razed to make way for the federally subsidized Parkview Tower apartments.

Washington Park was most dramatically impacted by two major construction projects. First, the completion of the Dan Ryan expressway, a fourteen-lane highway which opened during the early 1960s and reified the “classic barrier between the black and white south sides.” Second, the construction of the Robert Taylor Homes; a collection of 28 massive concrete public housing high-rises stretching from 39th Street to East Garfield Boulevard. As Black middle-class families began to follow the earlier exodus of white residents to the suburbs, poor and working-class Black households became increasingly isolated. They were separated from the rest of the city by, to the west, the Dan Ryan, and to the east, Washington Park itself. While the neighborhood experienced a slight bump in population between 1960 and 1970, this was primarily the result of its remaining residents (and displaced African Americans from other areas of the city) being herded into the largest single tract of public housing in the nation.

As the fortunes of Ebony and Johnson Publishing soared, Washington Park stagnated. In 1971, Johnson Publishing moved into a custom-built new headquarters on the South Loop, described by its founder as “a poem in marble and glass which symbolizes our unshakable faith that the struggles of our forefathers were not in vain.” In tandem, Johnson relocated his family from Hyde Park to Chicago’s Gold Coast By 1985, Ebony claimed to reach more than four in every ten adult Black Americans every month, a number that constituted “the highest market penetration of any general interest magazine in the nation.” Between the early 1960s and the late 1980s, the magazine’s circulation more than doubled, helping Johnson Publishing to establish itself as the largest Black business enterprise in the country.

During the same period, Washington Park lost more than half its total population. Those who remained became increasingly deprived, with the decline of Chicago’s stockyards and manufacturing sector hit working-class Black Chicagoans the hardest. By 1990, Washington Park’s poverty rate was approaching 60 percent, making it one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. Vacancy rates soared and empty plots proliferated. Buttressed by the Dan Ryan Expressway and the Robert Taylor Homes, Washington Park residents found themselves on the wrong side of “a physical barrier of brick and steel and concrete that separates black from white, rich from poor, hope from despair.”

5619 South State Street appears to have been sold off by Johnson Publishing during the late 1960s, most likely as part of a broader fundraising project to secure funds for its new Loop headquarters. During the 1970s it hosted the Church of Today, a Black congregation led by pastor Mother D. Bingham, and then an eatery called Ike and Thelma’s Fresh Fish. Building permit and inspection records indicate that, by the following decade, ownership of the property had passed to a one Raymond Martin of South Racine Avenue. In 1995, Ebony celebrated its fiftieth anniversary with a photo editorial that included an image of 5619 South State, described as “a modest one-story duplex,” alongside its more prestigious later headquarters. While remembered nostalgically as “the first building to house Ebony,” 5619 South State was a reminder of how far Johnson Publishing had traveled from its inauspicious roots.

However, like other Black legacy media companies, Johnson Publishing ran into difficulties during the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. The company struggled to maintain advertising and circulation revenues, and its ham-fisted attempts to negotiate the transition to online content compounded these problems. When Johnson passed away in 2005, his body lay in state at the company’s South Loop headquarters. Five years later, the building was purchased by Columbia College Chicago. Ebony was sold off to a private equity firm in 2016 along with sister publication Jet, and several years later Johnson Publishing filed for chapter seven bankruptcy. Its iconic South Loop headquarters was offloaded to redevelopers and reopened as an upmarket condominium complex.

The decline of Johnson Publishing has occurred against the backdrop of a continuing exodus of Black Chicagoans. In 1980, Black residents constituted around 40 percent of Chicago’s total population. Today, that number is less than thirty percent. This decline is rendered particularly acute in overwhelmingly Black neighborhoods such as Washington Park, where the population bottomed out at eighty percent less than its 1950 peak. Recent data from Chicago Planning Agency and the Washington Park Housing Data Project indicates that the neighborhood’s median household income is around $25,000, compared to a city average of $53,000, and thirteen percent of housing units are owner-occupied, compared to a city average of 44 percent. An extraordinary 44 percent of properties are classified as “inactive” – either vacant buildings or vacant lots. This, as of early 2023, appeared to include 5619 South State.

Ebony’s founding headquarters is an ordinary building with an extraordinary history. From this small storefront office emerged perhaps the greatest of all African American periodicals; a magazine that gave voice to millions of readers and gave shape to modern Black life within and beyond Chicago. Amid the ravages of urban renewal, economic decline and outmigration, 5619 South State is a reminder of Washington Park’s vibrant past and its historic importance as a center of Chicago’s “Black Metropolis.” That it still stands today is its own small miracle. It is evidence that people still live here. That Washington Park, despite its troubles, perseveres. And, perhaps, it is a reminder of what Washington Park could become again.

E. James West is a writer and academic, based at University College London. His research focus is on Chicago’s Black press, including his recent book A House for the Struggle: The Black Press and the Built Environment in Chicago(Illinois, 2020).