And there’s a thing that happens when you get into the Calumet region—that’s the name for the area on the southern shore of Lake Michigan, stretching across northwest Indiana and up into south Chicago. Because it has a distinctive smell, an industrial odor.

TRANSCRIPT

INTRO

Frank Vargo: It was a Saturday morning. And I remember it was very hot. And my brother and I were sleeping in our bedrooms over there, and couldn’t sleep because it was hot.

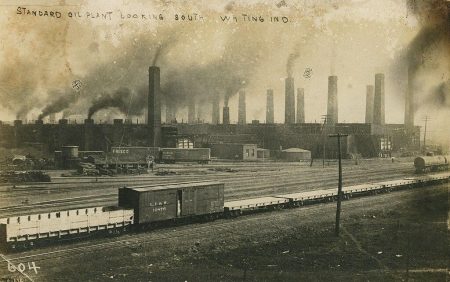

HOST: It was 1955, and Frank Vargo was six years old living in Whiting, Indiana—an industrial community on the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Whiting was a company town, and the company was Standard Oil, whose massive Whiting Refinery sat right in among the neighborhoods.

FV: I was just laying in bed. I was wide awake. …And all I remember is a tremendous blast, and my mom jumping up in the other bedroom yelling, you know, “What’s going on?” And we all ran of course to the kitchen window, which was facing the refinery. And to me as a little kid, the fire looked like it was in our backyard.

HOST: A twenty-six-story hydroformer—the largest in the country—had exploded. It shot a mushroom cloud eight thousand feet into the air and ignited a forty-acre fire with thousand-foot flames.

FV: Our house was about a half mile, actually, from the blast itself. So we were very, very close to it. Luckily, the house did not have any major damage. There were a couple of windows broken in a garage and so forth. But luckily there was no physical damage to the house. To my brother, my mom, and myself.

HOST: Frank Vargo’s family evacuated to his grandmother’s house a mile further away.

FV: We didn’t stay at my grandmother’s that long, because about noon, the fire chief or whatever ordered an evacuation of even the area where we were at. And I remember on the corner of my grandmother’s house, there was a store…right across, and there was our school, the school I attended, Immaculate Conception. And it was a three-story building. And I remember the flames were way up above the three-story building. You could just feel the heat, and you could just see the flames billowing.

HOST: So they drove to his aunt’s house, which was even further away. Also in Whiting. And then, after a couple of explosions rocked the city, they left Whiting completely for nearby Hammond. They didn’t return for two days. And, Frank told me, things were strange after that.

HOST: So what do you remember about the aftermath? What was your, kind of, experience of that the next few days?

FV: Back in those days, you didn’t talk about, you know, things that people respond to today—like, you know, veterans and so forth. They have nightmares and flashbacks to when they were in combat. Well, to me as a little kid, you know, I felt the explosion kind of shook me up more than I actually thought it would. And I didn’t remember some of these things for a while. But eventually, you know, I realized it did have an effect on me personally.

# MUSIC: THEME

Source: Steven R. Shook collection (CC BY 2.0)

HOST: From Belt Magazine, this is Fire!––a podcast about industrial fires in American life. I’m Ryan Schnurr. This episode, episode three, takes us inside the 1955 inferno at the Whiting Refinery, and what it meant for the region.

I’ve passed this facility hundreds of times. I grew up in Indiana, lived and went to school in Chicago for a while. Now I’m back. But I still pass the Whiting Refinery regularly—on Amtrak or south shore trains, or drives into the city. If you’re taking interstate 90, the toll road, you’re only about a mile away.

And there’s a thing that happens when you get into the Calumet region—that’s the name for the area on the southern shore of Lake Michigan, stretching across northwest Indiana and up into south Chicago. Because it has a distinctive smell, an industrial odor. Which, from what I can tell, is a combination of a few things: Sulphur dioxide from the U.S. Steel Plant. Fermenting corn. Maybe the emissions of a soap factory, and other miscellaneous chemicals and byproducts. And gasoline from the BP Whiting Refinery.

It’s the smell of industry, which is to say it’s the smell of transformation—a byproduct of the sorts of processes that take oil, coal, metals, sand, and other raw materials, and turn them into products for consumption. Fire is a fundamental part of this process. But the intention, generally, is to contain its effects and channel them toward production.

So what happens when it breaks free, and the consequences of an industry spread through the community? When it crosses the boundaries we have so painstakingly imagined between nature and culture and industry, and we become aware of our new and volatile reality?

When the boundaries we have so painstakingly imagined, between nature and culture and industry, collapse, and we are left staring into a new and volatile reality?

That’s the story of the Whiting Refinery.

#MUSIC

[TAPE] SUNRISE DOC: Even though the skies were often dark and dreary, the future looked brilliant and bright in Whiting, Indiana…

HOST: In 2015, the Whiting-Robertsdale Historical Society released a short documentary on the 1955 explosion, titled One Minute After Sunrise. The project begins with the arrival of Standard Oil.

[TAPE] SD: It was 1895. Just six years earlier, Whiting was not much more than a stop on the rail lines to Chicago. But in 1889, Standard Oil Company built a huge refinery in Whiting.

John Hmurovich: When the refinery came here, it changed everything.

HOST: John Hmurovich is a local historian who worked on the documentary—along with Frank Vargo—and who also wrote a book of the same name.

JH: People give the birth date of the birth of the town of Whiting as 1889. All that means is that’s the year Standard Oil came. The birth date of this town is the birthday of this refinery.

HOST: Standard Oil began in Cleveland, Ohio in 1870, with a single refinery. By 1872, it ran every refinery in the city. By 1880, it controlled ninety percent of the refineries in the country.

Jonathan Wlasiuk: They are a colossus at this time. And it is difficult to try to provide some sort of perspective. You have to go to, like, Amazon today, to get a sense of the scale at which they are operating and how much control they had in their space.

HOST: That’s Jonathan Wlasiuk, who wrote a book about the rise of Standard Oil called Refining Nature.

JW: By the end of the twentieth century, they are living what I describe as the libertarian dream. Zero, almost zero worker rights, zero regulation, and free reign for a company with a lot of capital to do whatever they want.

HOST: In the late 1880s, Standard Oil moved west—Rockefeller wanted to feed emerging energy markets in the interior of the country, and he needed a refinery with access to the railroad and shipping networks around Chicago and Lake Michigan. But he didn’t want to put his new facility in a city, because space was limited, and because any regulations that did exist were pretty much concentrated there.

JW: So he looks right across the border…at this little sleepy railroad crossing. There’s not a lot there. But for him it’s ideal, because he can fully realize the dream of efficiency, and kind of create the perfect habitat, if you will, for his new refinery which is going to be the biggest on the planet at that time.

# MUSIC

HOST: The southern shore of Lake Michigan, historically, is a mix of marsh and dunes—enormous sand hills, twenty or thirty feet high, swept up over centuries. It’s hard to build a factory in a landscape like this, so Standard Oil had to rearrange. They leveled the dunes and drained the wetlands.

JW: They either use French tiles, or they just set up, like, sewer drains directly out into the lake…In the early days, they are going from tank to tank in rowboats because the water is still that high. It hasn’t been drained yet. …They move the grand Calumet river a half-mile north of where it was running—then canalize it, they create a canal. And they also create what is called Indiana Harbor to serve as kind of a new port on the lake there so that they can ship out goods and receive them.

HOST: And the community of Whiting begins to form around this developing facility. Neighborhoods crop up, including one across the street from the refinery, called Rockefeller Park, which is renamed Stieglitz Park after Rockefeller sues them for using his name.

JW: And it is everything that a company town would be, from, you know, having the company control the housing and the government… Of the first seven mayors, four of them worked at Standard Oil Company while they were mayors. Two of them were superintendents at the refinery…

HOST: U.S. Steel moved in. So did ArcelorMittal. The municipalities of Gary and East Chicago incorporated, squeezed up against each other like rowhouses. The wider Calumet region, as it’s known, became one enormous factory, with Whiting its most prominent factory town. Here’s John Hmurovich.

JH: Everything revolves around the refinery. And at one time everybody worked there. And that’s hardly an exaggeration—maybe just a little bit. Not everybody, but boy, close. …The city was dependent on the refinery, the refinery was dependent on the people who worked there, and they had a good relationship.

[TAPE] STANDARD OIL PROMOTIONAL FILM: On American highways, from one end of the land to the other, there is no more characteristic or familiar sight than the oil truck, making its deliveries to farms and factories, to homes and service stations. For in the highly industrialized society the American people have developed, oil and oil products play a great part.

HOST: In the early years, Standard Oil was mostly producing kerosene. But by the twentieth century, oil was king. Petroleum made its way into nearly every aspect of American life, from plastics to asphalt to food production to gasoline.

SOPF: Oil provides power and lubrication for the complex mechanism of the American economy.

HOST: Oil production is an inherently dirty, dangerous business—pumping the highly flammable, fossilized remains of plants and animals from deep in the earth, shipping them hundreds or thousands of miles, and then heating, pressurizing, and otherwise combining them into products like gasoline and asphalt. And fire is a key part of the process—from the flares burning off natural gas on top of oil rigs to the flame in the cylinder of every internal combustion engine blazing down the highway. And the linchpins, refineries, are essentially one big fire, perpetually burning behind a few inches of steel and a barbed-wire fence.

# MUSIC

HOST: There’s a lot of chemistry at a refinery. For example: distillation, when crude oil is pumped through a furnace and separated into components—called ‘fractions’—by boiling point.

JW: In the early days, when you refined, say, a barrel of crude petroleum, you could get about seventy percent of that into kerosene, twenty percent would be gasoline, and the remaining ten percent would be things like lubricants like vaseline, asphalt, just really–tar, those really heavy residuums.

HOST: Eventually people figured out how to convert these products into all sorts of other things through processes like ‘cracking.’ Crackers are enormous rocket-shaped tubes that use furnaces, catalysts, and other pressure-exerting elements to break (or crack) hydrocarbon molecules. Cokers are a type of super cracker that turns residual oil into products including petroleum coke, or petcoke, which is basically a dirtier coal.

The final products are treated, blended, and then stored temporarily in massive tanks at or near the refinery, surrounded by a network of pipelines, railroads, and highways, which transport these oil products all over the country, propelled by, among other things, diesel and gasoline.

JW: The air pollution, it clung to everything. You have journalists from Chicago write about the housewives who are outside hanging their clothes on the line, and the clothes just get speckled with the fallout, the soot that is coming from the pollution.

HOST: Through the whole process, oil and other chemicals and byproducts are leaking out of pipes and tanks, soaking into the ground and water table.

JW: The drainage program they initiated of course killed the wildlife habitat. But, probably more significant for the human population is all the acids that Standard Oil and the steel plants to the east are dumping into the water system there are going into Lake Michigan. And Lake Michigan is the source of drinking water for all the communities around there, including Chicago. In the absence of any regulation to say “you can’t do that,” they just dumped it down into the nearest drain, or into the nearest river or tributary.

# MUSIC

HOST: By the turn of the century, regulations on businesses had become a little more stringent, but mainly on the commerce side. One of them is the Sherman Antitrust Act, which is supposed to keep one person from controlling too much of an industry and affecting “interstate commerce.”

In 1911, after some tremendous muckracking by the journalist Ida Tarbell, the federal government forced Rockefeller to divide his empire. Standard Oil splintered into thirty-four separate companies, most of which survive today in one form or another, under different names: Exxon, BP, Pennzoil, Amoco, Chevron.

The refinery at Whiting continued to be integral to U.S. oil production, eventually under the Amoco name. (It’s now operated by BP.) For a while, it distilled boron-10 for the Manhattan Project. But mostly it produced gasoline and related products and byproducts.

In 1955, the refinery, which was by that point one of the four largest in America, built the country’s largest hydroformer, a two hundred and fifty foot tall tank with steel walls up to three inches thick. It was specifically designed to produce high-octane gasoline.

Then, on August 27, 1955…

[TAPE] UNIVERSAL NEWSREEL: Whiting Indiana is almost engulfed in flames and smoke that roll four hundred feet into the air as an oil refinery fire runs amok…

HOST: The hydroformer exploded.

[TAPE] UN: Upwards of four million gallons of high octane gasoline pose an almost impossible task for firefighters, summoned from every surrounding community. In addition to the towering flames, a series of blasts rocked the entire countryside.

HOST: It was only around six months old at this point, and had been shut down temporarily for maintenance. While it was offline, a valve malfunctioned, mixing oxygen and highly flammable gases inside the hydroformer and transforming it into a twenty-six-story bomb. And that morning, when the workers went to start it back up, it detonated.

[TAPE] UN: Despite heroic efforts, the explosions hurled tons of steel from storage tanks into the community, making a shambles of houses and causing two deaths. The force of the blasts can be seen from the caved-in walls and windowless residences and upended cars tossed for several hundred feet. Before the holocaust had been brought under control, damage estimates had reached ten million, in one of the worst fires of its kind on record.

JH: Everybody that we spoke to said that there were probably one or two events in their lives that they remember.

HOST: Hmurovich again, talking about the documentary he worked on at the historical society.

JH: They remember—if they’re old enough, they remember Pearl Harbor. If they were a little bit younger, they remember when JFK got shot. And everybody else, everybody we talked with said the other thing to remember is this explosion, because this explosion just seared into the minds of people.

HOST: The hydroformer was ripped to shreds. Shrapnel flew everywhere. It landed on homes and railroad cars. One five-ton piece crushed a grocery store. Another piece landed in the bed of three-year-old Ricky Plewniak, who was killed instantly. His brother, Ron, lost his leg, and more than forty other people were injured. Meanwhile, a fireball unfurled thousands of feet into the air. One paper wrote that the mushroom cloud “obscured the sun and turned day to night.”

JH: It was just so frightening. So massive. People thought their lives were in danger. People thought initially, some did, that the Russians had dropped the atom bomb on us, and this was—this is what we were experiencing. Some got on their hands and knees and started to pray, because they were convinced this was the end of the world.

# MUSIC

HOST: Back at the refinery, steel fragments from the hydroformer punctured holes in the oil tanks, which began to leak all over the floor of the facility. The oil caught fire and spread. By noon, it covered forty acres of land.

The refinery had its own fire department, which went to work with support from departments in Whiting, Hammond, East Chicago, Gary. But the fire was too big, and covered too much land—they couldn’t get close enough to put it out. Their only hope was containment.

Miraculously, the men who had been working on the unit survived. The only other casualty—besides three-year-old Ricky Plewniak—was a foreman at the refinery, who reportedly suffered a heart attack.

Within a few days, Standard Oil’s fire department had the blaze under control. One week later, the last rogue flames were put out.

# MUSIC

JW: When they constructed this refinery, they had a lot of experience with fire.

HOST: John Wlasiuk, talking about Standard Oil.

JW: They built, kind of, levees around all of the tanks, because they knew what happens is, if you have a fire, eventually the tank usually will rupture, even if you use, like, good hearty steel. And that flow of at times millions of gallons of burning petroleum is really dangerous—not just to bodies, but they were concerned about property.

HOST: In other words—if you’re Standard Oil or any other oil company running a refinery, you basically know something like this is going to happen eventually.

JW: And so by simply building, like, a levee around it, that levee exists to hold all of that burning material. And you still see it today, if you go to refineries. They have the same thing.

HOST: Of course, even a levee can’t manage an explosion like the one in 1955. So you prepare for that eventuality, too.

JW: John D. Rockefeller writes about it, even in the early days, that it’s just part of doing business…and they write about it so casually, even when people die, that it’s like, ‘okay, well, you know, we got to start going again, let’s make sure we get our fire insurance going.’ Which is also what they did in this fire.

HOST: The neighborhood across the street—the former Rockefeller Park, since renamed Stiglitz Park—had gotten the worst of it. Two hundred homes were damaged. Standard Oil used its insurance payout to buy and bulldoze a hundred and forty of them, relocating their occupants. Hmurovich says this marked a kind of turning point for Whiting.

JH: After this explosion, things changed. …It made everyone feel vulnerable for the first time. And that then eroded some of the trust that people had in the refinery.

JH: Because this was the first time that anyone outside of the refinery got killed. This is the first time that anyone outside the refinery had their homes damaged. This was the first time it wiped out a whole neighborhood…And beyond that—even though Standard Oil said…we won’t lay anybody off as a result of this, and they didn’t immediately—but what happened was this was like urban renewal within the refinery.

HOST: The company started replacing all the old equipment, which had been destroyed by the fire, with the latest technology. And this technology was beginning to replace some of the tasks that had previously been done by people.

JH: And so in the years which followed—nineteen fifty-eight, fifty-nine, three or four years after the refinery explosion—people started getting laid off in massive numbers. …And it then eroded one more thing in the community.

HOST: Over the years, more and more workers and their families moved out of Whiting, an exodus made possible in part by the very gasoline produced by the refinery.

JH: There were seven thousand people working in the refinery at the time of the explosion, but today it’s down to under eighteen hundred I think. Massive numbers of people are gone. That time when everybody said, oh, you know, everybody’s working at the refinery, everybody’s got a connection to the refinery, that day’s gone—now it’s tough to find anybody in this town who has a connection to the refinery.

#MUSIC

HOST: But that’s not the end of the story. Because, of course, the refinery is still there. And its less spectacular effects are still being revealed. So I called my friend Ava Tomasula y Garcia, a fourth-generation resident of northwest Indiana.

Ava has written a lot about the Calumet over the years, including one of my favorite pieces ever, for Belt Magazine. It’s called “What Indiana Dunes National Park and the Border Wall Have in Common.” Full disclosure: I was the editor on that story. Anyway, look it up.

Ava Tomasula y Garcia: It’s the most incredible landscape I’ve ever been to, because you’ll turn one way and you’ll see a Unilever factory, you turn the other way, there’s a just, you know, a kind of beautiful lake with swans nesting on it. Because the Calumet has kind of retained that character as a—as this kind of incredible wetlands area even through, you know, a hundred-plus years of pollution.

HOST: Ava’s now at Columbia University, working on a PhD in anthropology. She’s focusing mostly on the ongoing health effects of the region’s industry.

ATG: So of course, we all know about these kinds of monumental diseases and their ubiquity in the Calumet. You know, certainly in my family, there’s just many, many painful histories of cancers, dementia, asthma, these things that that people know are linked to…working in steel mills, working in the air polluted by BP, Amoco, and a million other industries.

HOST: She said one of the biggest challenges for residents is these “undiagnosable illnesses,” or when you get sick from living around pollution and contaminants—like an oil refinery and its waste products—but you can’t link them to any specific source.

ATG: And yet, because of how shitty the laws and how shitty our, kind of, medical understanding of a cumulative trauma of pollution exposure, you know, these are illnesses that are never going to be able to be directly attributed to these corporations. There’s never going to be a kind of restitution or any way to say it was this source, specifically, that gave me this disease or anything like that.

HOST: And this gets at, I think, one of the most interesting aspects of the relationship between people and the refinery. They’re not only connected economically and geographically. There’s a chemical, elemental connection. The fire of 1955 was the most obvious manifestation of this, when it literally spread into the community. Or Standard Oil smoothing out the dunes.

But it’s much bigger than that. Industrialization is not something that got tacked onto some pre-existing state. It’s a fundamental restructuring of nature. It’s a new social and economic and environmental compact, in which people bent the arc of our biological relationships toward extraction and consumption—toward an endless fire burning on the southern shores of Lake Michigan.

ATG: Looking at the Calumet, you know, the Whiting, landscape, it’s just so clear that there’s this other kind of duality that just doesn’t make any sense as division between the discursive and the geologic, or the natural and the, the man made. The stuff we’re talking about is—it’s not either/or, natural or not, you know, geologic or material. But it’s somehow existing in the space where it’s impossible to make the division between those two things to begin with.

# MUSIC

HOST: Years ago, I went to Whiting and drove around the refinery with a local activist named Thomas Frank. I went back recently to jog my memory, and ended up just standing around staring at cokers. I thought about what Ava had said, about how the refinery is part and parcel of this new and volatile nature, the one we’ve constructed out of oil and steel.

It’s easy to understand the bargain Whiting made early on—tolerating the inherent dangers of the refinery in exchange for wealth and amenities, so long as Standard Oil would keep its dirty business contained. But this idea was never truly possible. Not really. As Luis Urrea once wrote, “There is no here or there. It’s all here.”

Here: where the Whiting refinery burns on the southern shores of Lake Michigan, a slow-motion disaster unfolding behind—and beyond—its walls.

# MUSIC

CREDITS: This episode was written and produced by me, Ryan Schnurr, with editing by Dirk Walker. Production assistance from Cassidy Duncan. Theme music by Michael Bozzo. Additional music by Jahzzar. Archival recordings courtesy of the Whiting-Robertsdale Historical Society, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, and Periscope Films. Special thanks to everyone who spoke with me for the project, and to Anna Schnurr, Ray Fouché, Shannon McMullen, Rachel Havrelock, Sharra Vostral, Emiliano Aguilar, Alex Chambers, Ed Simon, and the members of the Whiting-Robertsdale Historical Society.

Fire! is a production of Belt Magazine and Fortlander Media. Support for this project came from Belt readers and members, Indiana Humanities, the Purdue University Department of American Studies, Jim Babcock, and the Albert LePage Center for History in the Public Interest. You can find links to sources and further reading, along with more episodes, at beltmag.com/fire.

Next time, we’re headed underground, to the site of Pennsylvania’s forever fire. See you then.

Selected sources and further reading:

John Hmurovich, One Minute After Sunrise: The Story of the Standard Oil Refinery Fire of 1955

Jonathan Wlasiuk, Refining Nature: Standard Oil and the Limits of Efficiency

Ida Tarbell, The History of the Standard Oil Company

Documentary: One Minute After Sunrise

Standard Oil Promotional Film (circa 1940s), digitized by Periscope Films

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, NPMS Public Viewer

National Archive and Records Administration, “Oil Blaze and Blasts Sweep Town”

Ava Tomasula y Garcia, “What Indiana Dunes National Park and the Border Wall Have in Common”

Ryan Schnurr is the author of In the Watershed and writer for hire covering climate, culture, infrastructure, and more. He used to edit Belt Magazine (and still writes there sometimes). He is also the creator of the forthcoming podcast series Fire!, on industrial fires and climate crisis in American cities. Ryan received his PhD and MA from Purdue University and the University of Illinois at Chicago, respectively, and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Humanities and Communication at Trine University.