By Clare Welsh

FAIRY TALE

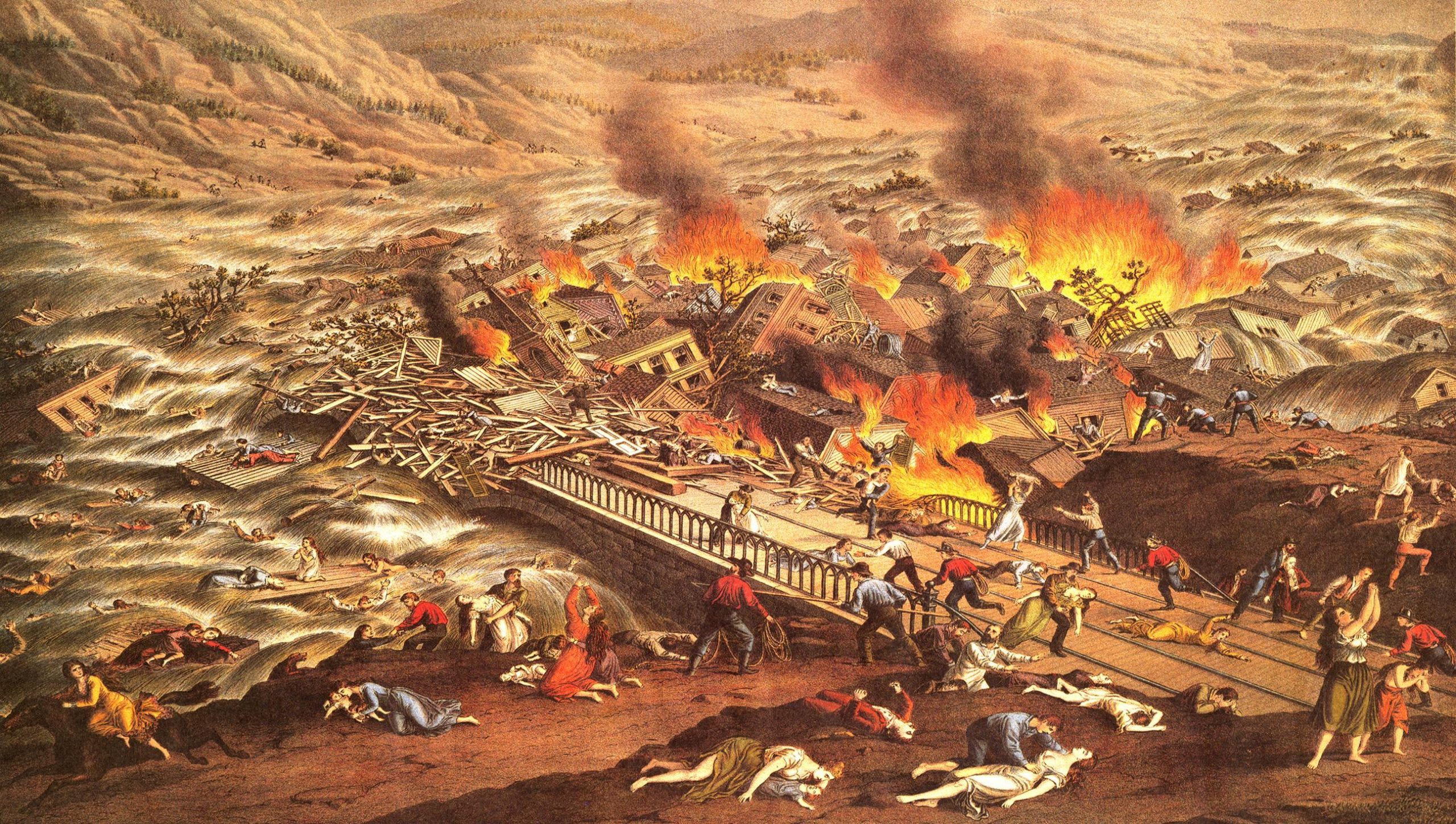

After The Great Conemaugh Valley Disaster, Flood & Fire at Johnstown, PA, 1889

The town was once empty

light underwater.

There was no air.

And you wonder

why the men don’t speak.

Why the women

obsess over each turning

shoulder in the night—

This from the landlady

with dandruff and cigar ash

falling from her sleeve.

Anyway–

She trails into silence.

Who here

ever finished a sentence,

coughed up one

needful shape of love?

Hard to speak of tomorrow

with so much

yesterday pushing down

each cringed vowel.

The valley remembers

the black lake

like any crushed weight :

With daisies

thrust through fishbones,

foundations, the busted

stone dam

scattered as tossed knuckles

with fox teeth, car parts,

bent beer cans.

And if I meet a man at the base

of this green grave,

what of it?

The catholic garden

with its crossed wilderness

thickens the dusk,

whose glistened

frog throat croons

fucksong to the river.

A man strokes

the inside of my thigh

and the housewife in me

rises like a snake: another

copperhead I must shoot

from the back porch

of my mother’s

bold inheritance

of sacrifice.

If this were a fairytale,

if I were a child,

I would have been

orphaned

to a stepmother:

Do not, and I mean

do not let him

knock you up. The landlady wipes

blonde ale from the corner

of her dry lip.

Anyway–

⤕

The man unfolds

an antique etching

of the Johnstown flood.

The image seems

an omen, a gold weight

I must carry

in hope of trading

down the road

to some

cloaked pawn shop

in exchange for my own

wisdom, or beauty, or–

later, the etching hangs

in a room we share.

In the scene, people

like pale termites

swarm, the women

with waists

cinched, the men

in gray shirts pulling

splinters from water.

The waves carry

houses burning

to the horizon, visible

beyond the mountains

that–despite or

because of this violence–

appear gentle, stoned

onlookers gazing

dumb at the edge of grief.

On the riverbank,

foam, silt, gathered

bodies: A woman lays

with a still child.

A man stares

stoic at the breast

of a drowned woman,

her ankle twisted

under the hem

of a white dress.

A woman weeps.

A man makes himself useful.

The people die in shapes

of dolls. There is

the good mother.

The bleak father

rolling up his sleeves.

The water rises,

the smoke drifts,

no one unlaces

her corset, takes off

his strong face.

⤕

One social theory suggests people revert to so-called traditional gender roles in times of disaster; of course, any American saying traditional usually means colonial, that rigid urge to sequester the wilderness–the fire, the water–into fenced outlines of one man, one woman. This may explain the Victorian melodrama in this 1889 depiction of the Johnstown Flood.

Nothing is more attractive than a familiar pain. Here comes the highway billboard promising a return to greatness: It was great, then, wasn’t it, when she was holding the baby like a wisped ghost, when he was standing with his button-down shirt by the wooden chair, a photo of an industrious family developed on a glass plate, a glass family, fertile, glowing, god-fearing. They knew their place. They weren’t so complicated, so angry, then, when people were great, when everything was just so.

This may explain the doll people in the 1889 etching of the Johnstown Flood. Or, in 2017, this headline in Politico Magazine: “Johnstown Never Believed Trump Would Help. They Still Love Him Anyway.”

This may explain the cult of motherhood. The monument to fetal tissue in the Catholic cemetery. The nice church ladies who paid for the white granite, who keep paying for it.

This may explain the etching. The woman still laying with the child. The child laying still. The man with his rolled-up sleeves. The man and his witnessing to. The drowned.

She died how she lived: With her stomach sucked in.

He died how he lived: Never weeping.

This might explain the etching of 1889. Or my inability to relax until I finish dinner, dry the dishes, ask some man how he’s doing: Does he need anything? Can I get him some tea, a beer, some coffee maybe? Is there anything I can do here, anything, anything at all?

⤕

It’ll work only if you

make more money

than him, only if

you own the house,

trust the men here

always want

something in return,

if not some pissed

baby miracle, some kind

of mothering

from a woman, you get

nothing for free.

The landlady grips,

yanks a vine

from the side

of the row house.

Beneath the ivy,

a pale latticed

wood lace.

Anyway–

Landscaping,

Forty dollars.

Later, stripping

my clothes, seams

leave red lines

In hips, back, thigh.

What was I

supposed to do

with this,

the shape of my life?

⤕

Sex on the edge

of the church yard:

no moon, stars

or cars thrill

the darkness,

no world visible

we wreathe wrists

in the cold grass

hands reach

in and around

all the growing

flesh we cannot see.

⤕

In Pennsylvania, fairy tales follow Germanic logic:

Don’t go into the woods after dark. The wolves will eat you. The witches will seduce you.

If you are a boy, your task is to kill the wolves

and burn the witches.

If you are a girl, your task

is to outpace the wolves and betray the witches,

particularly those within,

to the boys.

The old woman will have what you need

though she is ugly, though you should work hard

to never become her.

Interweaving these fairytales are colonial directives:

This land is yours and you are

nothing if you do not own it. To own it you must earn your life. To earn is to take is to hurt is

to hunt hurt back, a cycle to nowhere, this

hero’s journey stuck

fidgeting under the boot.

Wealth is the only initiation.

You must initiate yourself.

Until then, do not speak of love.

Love without money is reality TV.

Love without money is a social media post about a mother

overdosing in the front seat of a car.

You’ve seen what they do to women like you.

⤕

Images of colonial gender roles resemble religious iconography: Here it comes again, the highway billboard of Donald Trump in rays of light, with white Jesus resting a hand on the shoulder of his bloated business suit. Here comes white Jesus with his heterosexual entourage of twelve men. With his chaste, baby-faced Magdalene turning her cleavage to the wine. Look long enough, and you’ll find in every icon a contradiction. This is why you can’t look long, if you want them to remain useful.

In the chaos of political upheaval, I could bypass the task of developing a complete consciousness. Put off the toil of mature spirituality by assuming the identity of an archetype. Ask this archetype to save me, save us with her white dress. His blue suit. Their snappy answer to the question of what to do about the flood, the fire, the children dying in schoolhouses carried by waves to the bright distance.

⤕

In the lower left

corner of the etching,

a woman in gold

gallops away on horseback.

If loss is the horse,

I am the rider.

Where I’m going,

I cannot carry

my mother

scrubbing the carpet,

boiling the eggs,

setting my sprained ankle

alone. The flood churns

trees and train cars

across the road.

I must find another.

I must find my own

face in the dark.

⤕

Every fifty miles or so, two billboards repeat. They repeat the entire length of the Pennsylvania highway, from the Ohio border to Philadelphia. The billboards ask brash questions:

Where are you going?

HEAVEN or HELL?

SHACKLED by Lust?

Shackled by LUST?

I am shackled by lust. I am going to hell on a horse I pulled from the mud of the Appalachian housewife I was expected to be.

I need the Appalachian housewife more than she needs me. Her eternal giving. Her Madonna mouth. Her pickling jar callouses. Her absolute lack of dreaming.

Housewife archetypes tidy every corner of America, but the Appalachian housewife is an especially impossible archetype to embody, for not only is she endlessly giving, but endlessly self-sufficient. She doesn’t ask for help. She is the helping verb itself, an invisible string. Her working-class station renders her a seamstress, a maid, a nurse to the families of Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Richard Murdock, Jeff Bezos–over a century of mad kings. With gray hands sifting over the dark, pointless mountains. The lost land.

Historically, the helping role of such women was pre-determined by colonial law; however, it’s not the old law, but my unconscious, internalized mirroring of it that corsets my spine. Tied in this shape, I put off the work of weaving a complete personality of desires, contradictions. Dreams.

This rigid archetype is an avoidance tactic not only for me, but for potential lovers. In the same way the housewife embalms her peppers in vinegar, saves them from the bite of time, she saves her lovers from the task of maturing. She sweeps their crumbs. Apologizes for their gruff comments. Teaches them tenderness as she would a child.

She is the good mother and she was a good mother and I would not leave her now if I had any other choice.

I am shackled by lust. I am going to hell on a horse. The river floods from the house the altar cloth, the broomsticks, the sprigs of dried lavender. The old love spell carries itself away. I must wreath from the wreckage a new circle.

⤕

The landlady remembers

my man for his

beat black car.

You can do better

than that. Anyway–

I am learning her

transactional logic.

I do not

follow it

or any other

laid like a contract

on the table

of knife marks

and loose tobacco.

I am done with

faux ownership,

the oaths

of stepmothers,

good mothers, of

woodsmen, hunters.

When I love a man

I stroke the fur

of the wolf

inside him, the hair

of the witch in me.

It is like pushing

through a curtain,

feeling the warm glass

of a window looking out

at what the rain left

in the yard:

glint metal in grass,

a wet horse grazing

around white caps

of mushrooms

pulling themselves

soft and silent

out from the valley,

the cold body

of the flood.

Clare Welsh lives in Pittsburgh and was raised in Indiana County, Pennsylvania. Her writing focuses on the culture of this region. Here recent writing about the region can be found here in The Southeast Review , The L.A. Review , and Trampset . She is an editor at large for Fine Print Paper, a free poetry and art newsprint zine disturbed in Pittsburgh and beyond.