At 6:30 a.m. Saturday, a crowd estimated at 1,700 gathered for Mass at Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the Catholic church established by Italian immigrants 18 years earlier. By 10:30 a.m., the Knights of the Flaming Circle started gathering in a park at North Main and Federal streets in Niles, across the street from General Electric. They were armed to the teeth and setting up blockades to keep the parade from happening. “We’ll meet the Klansmen as they arrive,” one Knight of the Flaming Circle told a reporter from the Youngstown Vindicator.

By Vince Guerrieri

As October turned to November in 1924, a presidential election was winding down.

Calvin Coolidge, who’d taken office a year earlier upon the death of Warren Harding, was renominated in an exceedingly boring convention in Cleveland (prompting Will Rogers to joke that the churches were being opened just so delegates could hear some singing), and faced Democrat John Davis of West Virginia and Progressive candidate Robert La Follette.

Up in the sky, you could see the USS Shenandoah, the first of the navy’s new dirigibles, crossing the country from New Jersey to California. New York and Chicago were beset by Tong Wars in their Chinese communities. (It was rumored that some of the assassins involved in the New York war were brought in from Cleveland, itself home to a vibrant Chinatown … and beset by its own Tong wars.)

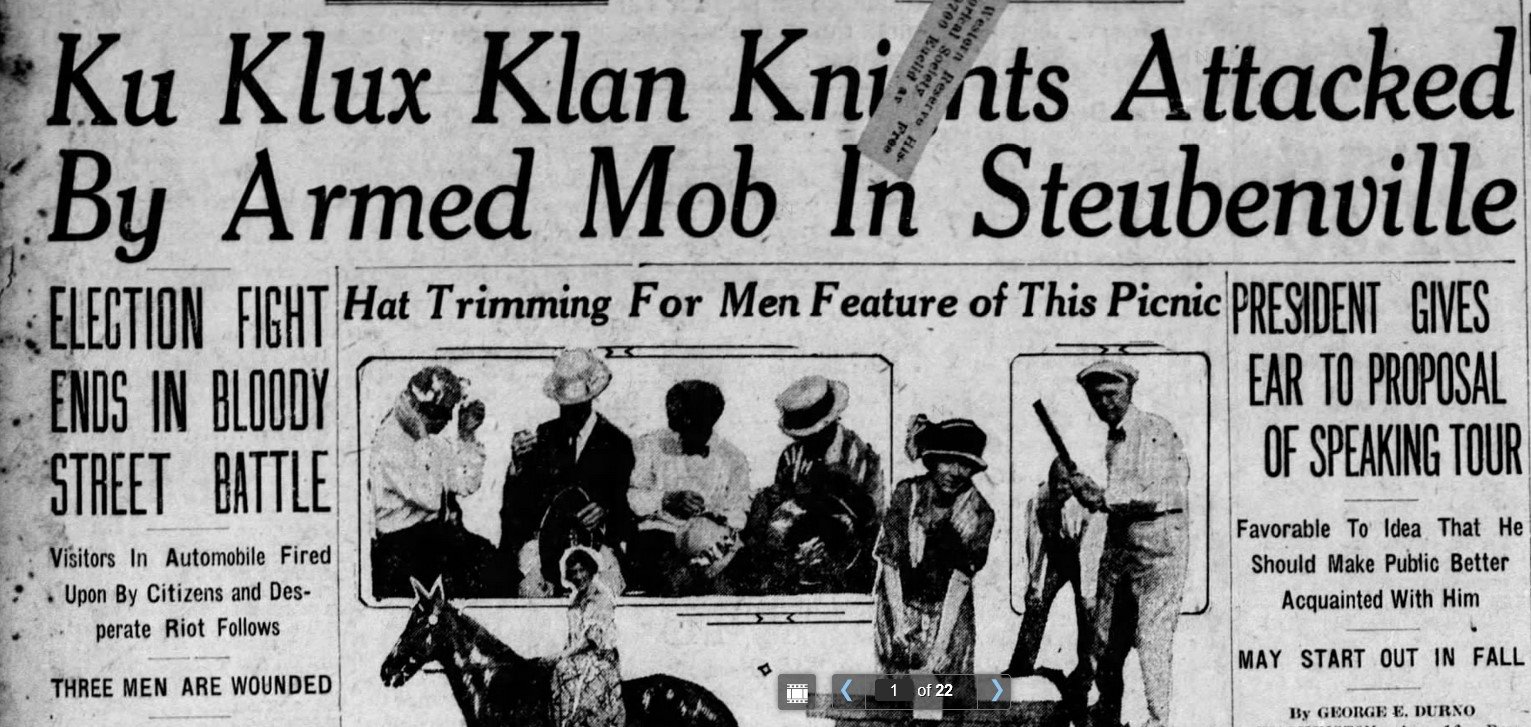

And the Ku Klux Klan was planning a parade in Niles, a reputed “sundown town” in the Mahoning Valley of Northeast Ohio, which had become a thriving industrial location in the 20th century.

The largely dormant Klan found new life in the early 20th century, not just in the south, but in the industrial north, where an influx of immigrants – largely Catholic – was perceived as a threat to the American way of life.

The Klan march in Niles would be a show of strength and triumph. The Klan had elected officials in a host of communities in Northeast Ohio and Indiana, where they had become ingrained, visiting schools to present bibles and American flags, and holding social gatherings at the local amusement park or at its own property in Canfield, just outside of Youngstown. (It was referred to as the Kountry Klub. Seriously.)

A permit was granted by the city of Niles for the Klan’s parade, scheduled for 2 p.m. Nov. 1. Mayor Harvey Kistler’s home was bombed early Oct. 29, and there was an attempt to broker an uneasy truce to allow the march to happen. But anti-Klan gangs patrolled the streets, and fights seemed to start as soon as the clock struck midnight on Nov. 1, the scheduled day of the parade. And then an explosion was heard in the distance.

The Ku Klux Klan’s roots date back to the days following the Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Tennessee, putatively as a social organization for Confederate veterans. But as it spread throughout the south, the Klan quickly mutated into a terrorist organization, using intimidation and violence to keep African-Americans from voting and otherwise integrating into society. Their actions inspired what became known as the federal “Force Acts” to stop violence. One of them was even called the Ku Klux Klan Act. But the President at the time, Ulysses S. Grant, was diverted by the Panic of 1873, as well as scandals within his own administration. Democrats took hold of most southern states’ governments, implementing restrictive laws against Blacks, and the Klan faded into the background, its mission now unnecessary at that point.

In 1915, D.W. Griffith glorified the early Klan in the nascent medium of film, directing “Birth of a Nation.” Cinematically, it was groundbreaking, using for the first time elements that are commonplace today, including split-screens, close-ups, fade-outs and a full musical score that would be played live to accompany the nearly three-hour-long movie. But thematically, it glorified the Ku Klux Klan while playing into fearful stereotypes of African-Americans (who were played in the movie by whites in blackface).

The movie’s arrival in Atlanta inspired William Joseph Simmons to gather a group and climb Stone Mountain, lighting a cross on fire at its summit. The Ku Klux Klan soon rose from its hibernation in the south – but also found a home in the north, which was undergoing its own rapid demographic changes.

The population of the city of Youngstown had tripled between 1900 and 1920. The city had become a massive steelmaking hub, and its open hearths were labor-intensive, requiring workers by the thousands. It soon became a land of opportunity for immigrants, largely from Southern and Eastern Europe. Many of them were Catholic, most spoke little English and in the 1920s, a lot of them viewed Prohibition as an inconvenience, not the law of the land. Cities like Youngstown and Niles had become known as havens for vices like gambling, prostitution and bootlegging.

The Klan saw itself as the defender of law and order and the American Way. The Klansman’s Creed included the belief in limited immigration, that native-born Americans have more rights than immigrants, freedom of speech and the protection of pure womanhood.

Catholics could never be true Americans, they reasoned, because of fealty to the Pope, whom they considered a foreign potentate. In fact, The Citizen suggested Catholics immigrated to the United States were spies that would savage Lady Liberty as “The Tiger of the Tiber.” Unlike the previous iteration, which resorted to violence, this Klan saw itself as a political organization, presenting donations and King James Bibles to area schools and encouraging them to be read in class. And the Klan started installing elected officials, including Charles Scheible, elected Youngstown mayor in 1923. Scheible’s campaign manager was a man named Evan Watkins, ceremoniously addressed as Colonel. A Welsh immigrant, Watkins himself could never join the Klan, but he was known as a spellbinding orator who used his gifts in service to the organization and served as the editor of The Citizen.

The Klan was welcomed immediately in the Mahoning Valley, raising crosses throughout the county, holding a rally in Wick Park in Youngstown and a massive Konklave in Warren in 1923. Also that year, the Klan bought 267 acres near the Canfield Fairgrounds for $40,000 for their own gathering spot, which was nicknamed the Kountry Klub. (Although the Klan newspaper, with a circulation of 25,000, continued to sing the praises of Idora Park, the trolley park at the end of the line on the South Side of Youngstown. Like many parks of its day, north or south, it was segregated.)

But it also brought opposition. In 1923, an organization formed in Kane, Pa., calling itself the Knights of the Flaming Circle. It welcomed all the people the Klan wouldn’t – Catholics, Blacks and Jews – and set itself as an anti-Klan organization.

By early 1924, it was estimated that there were as many as 7,000 members of the Klan in the Mahoning Valley. And it had developed as a potent political force. The Citizen crowed that 15 of 20 Klan-backed candidates had prevailed in that August’s primary in Mahoning County.

The Klan was determined to show its numbers before that year’s election and set a parade through Niles for Nov. 1. Predictably, it was met with resistance, and on October 30, a meeting was called in the hall at the McKinley Memorial, designed by McKim, Mead and White and opened just nine years earlier in memory of the Niles native who served as the 25th President. The goal was to find a peaceable resolution. Former state senator John McDermott urged Mayor Kistler to revoke the parade permit, but Kistler cited the Klan’s First Amendment rights to protest. Trumbull County Sheriff John Thomas asked for state intervention, which Gov. Vic Donahey denied, saying it would be bad precedent to send troops before any type of illicit activity had occurred. (Donahey, running for re-election that year, would be endorsed by the Klan.)

Camera crews and journalists filled the city’s hotels. Niles’ nine-member police force was exhausted – they’d been on duty for more than 24 hours straight – but continued to patrol the streets. The force would be augmented by 25 sheriff’s deputies, and Kistler swore in as many as 100 men, many affiliated with or at least sympathetic to the Klan, as auxiliary police.

The impending rally had effectively cancelled Halloween, the Youngstown Telegram said, with streets bare of trick-or-treaters. On the streets, however, were anti-Klan gangs, stopping people and searching them for weapons. Those with weapons were turned over to local police. That included Watkins’ two bodyguards. Watkins went with them to the police station to arrange bail, and was immediately put into a sheriff’s car and returned to Youngstown.

The bomb early Nov. 1 turned out to be an isolated incident in a field, perhaps to scare off both sides that might come to a fight, but shortly after it, eight shots were fired from a passing car on Main Street. Stories vary on how the altercation started, but one man, Frank McDermott, was wounded, and the crowd commandeered cars and gave chase. McDermott’s father John was one of the men who tried to broker peace between the two factions.

As dawn broke Saturday, Niles was relatively deserted. Business owners had boarded up their front windows. Many businesses were closed for the day. Buses refused to travel into the city. School boards in Niles and nearby Girard announced that afternoon’s high school football game between the two schools would be canceled.

At 6:30 a.m. Saturday, a crowd estimated at 1,700 gathered for Mass at Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the Catholic church established by Italian immigrants 18 years earlier. By 10:30 a.m., the Knights of the Flaming Circle started gathering in a park at North Main and Federal streets in Niles, across the street from General Electric. They were armed to the teeth and setting up blockades to keep the parade from happening. “We’ll meet the Klansmen as they arrive,” one Knight of the Flaming Circle told a reporter from the Youngstown Vindicator.

Klan members were gathered a little north of the Knights’ camp, just as heavily armed. They believed they had authority to carry guns due to Watkins’ co-opting a little used constabulary to stop horse thieves that was still on the books. He deputized what he called the “Ohio State Police” to keep fellow Klan members safe.

Then came an afternoon of brawling and gunfire. Knights of the Flaming Circle were stopping cars, extracting Klan members, taking their robes from them and sometimes beating them. Shots were fired, by both sides. “Into the Valley of Death rode the intrepid foolhardy Klansmen Saturday afternoon,” the Vindicator wrote.

At 1:16 p.m., Gov. Vic Donahey activated a National Guard regiment, with more than 1,000 troops from Youngstown, Cleveland, Akron, Barberton, Berea, Canton and Warren. An hour after that, martial law was declared. People who weren’t from Niles had to leave, and everyone had to be off the streets by 6 p.m.

At 2:30 p.m., a train pulled in to Niles’ Erie Railroad station, with 1,000 Klan members. It was just minutes after martial law was declared, so they never got off the train, and headed back out of town.

“I am of the firm belief that if the troops had been an hour later, there would have been a regular massacre,” said Col. L.C. Connelly of the National Guard. “Both sides were heavily armed. I do not think they wanted to fight, but they were afraid not to fight.”

It was four days before martial law was lifted. Ultimately, a Trumbull County grand jury returned no major charges related to the riot. Knights were believed to have acted in self-defense due to a “shoot to kill” order given to Klan members.

“The Klan is by no means through in Niles,” said Grand Titan Fred Warnock, a former mayor of Youngstown, following the riot. “We are more than ever determined to hold our parade there, and we will do it within a few weeks.”

But not only did they never march in Niles, they never marched anywhere in the Mahoning Valley again. The Klan’s local and regional power waned. A 1923 break-in at the Klan’s Youngstown headquarters led to the theft of a record book, ultimately identifying its membership. “Some of these men now administer your city’s affairs as well as schools,” stated a book that resulted, “Is Your Neighbor a Kluxer?”

D.C. Stephenson, the Klan leader of Indiana and one of the most powerful Klan figures in the United States, ended up standing trial for the kidnapping, rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer, a state employee working on a literacy campaign. The sordid story led to membership losses, and following his conviction, Stephenson started talking about the corruption in the Hoosier State government. (The Indianapolis Times won a Pulitzer for its coverage.)

Col. E. A. Watkins, the local Klan leader, made “a hurried and secret departure from Youngstown late in 1924 after an unfortunate love affair,” the Youngstown Telegram noted. The Ohio Klan overreached, trying to get laws passed banning interracial marriage and mandating bible reading in public schools. The Bible reading law came to Donahey’s desk. He vetoed it.

In 1931, the Kountry Klub was sold at sheriff’s sale for $7,955. But the Klan never fully went away. Obituaries through the 1930s could be seen noting that the deceased’s social memberships included the Klan. Watkins himself died in 1935, having seen the error of his ways, the Telegram wrote.

“My Klan convictions have changed,” he said, discussing a meeting of the Federation of Churches in New York’s Pennsylvania Hotel. “Here was a meeting of all creeds – Jews, Catholics, Protestants – and there was not a discordant note on the entire program. That meeting represents the world of religion in the future.”

Vince Guerrieri was born in Youngstown three weeks before Black Monday, and left there without ever really escaping it. He’s an award-winning journalist and author now living in the Cleveland area.