Every place in the world has a story, and every person’s journey through those places can change the path for those who follow.

By Julie Green and Kirk Johnson

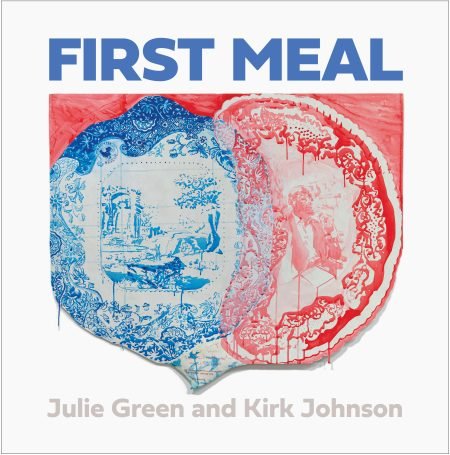

The following is an excerpt from First Meal by Julie Green and Kirk Johnson released by Oregon State University Press.

Summary: Wrongful convictions haunt the American criminal justice system, as revealed in recent years by DNA and other investigative tools. And every wrongfully convicted person who walks free, exonerated after years or decades, carries part of that story. From those facts, artist Julie Green posed a seemingly simple question: When you have been denied all choice, what do you choose to eat on the first day of freedom?

In the small details of life at such pivotal moments, a vast new landscape of the world can emerge, and that is the core concept of First Meal. Partnering with the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law, Green and her coauthor, award-winning journalist Kirk Johnson, have created a unique melding of art and narration in the portraits and stories of twenty-five people on the day of their release.

Food and punishment have long been intertwined. The tradition of offering a condemned person a final meal before execution, for example, has been explored by psychologists, filmmakers, and others—including Green herself in an earlier series of criminal-justice themed paintings, The Last Supper. First Meal takes on that issue from the other side: food as a symbol of autonomy in a life restored. Set against the backdrop of a flawed American legal system, First Meal describes beauty, pain, hope and redemption, all anchored around the idea—explored by writers from Marcel Proust to Michael Pollan—that food touches us deeply in memory and emotion.

In Green’s art, state birds and surreal lobsters soar over places where wrongful convictions unfolded, mistaken witnesses shout their errors, glow-in-the-dark skylines evoke homecoming. Johnson’s essays take us inside those moments—from the courtrooms where things went wrong to the pathways of faith and resilience that kept people sane through their years of injustice. First Meal seeks to inform and spread awareness, but also celebrate the humanity that unites us, and the idea that gratitude and euphoria—even as it mixes with grief and the awareness of loss—can emerge in places we least expect.

Julie Green:

I sew. Mom taught home economics and still sews my skirts. It seems I could sew before I could walk. And I was shaped by the places I’ve loved. This painting captures an Illinois first meal, but a friend from China said it looks Asian and it does. I was born in Japan, lived there as an adult, and am fond of Asian design.

Exoneree Patrick Prince had a delicious first meal of rock shrimp and grits at Little Goat Diner in Chicago. A gold sun represents the grits, and the corn from which grits are made is the gold of the Midwest. Peering out from behind a cliff is a plastic goat head logo, cut from a bag in our closet that held a new cashmere sweater. I look around and use what’s on hand, improvise, recycle. The gingham cliffs are cut, sewn, quilted.

Shrimp are creepy-looking but tasty. I planned to make a few decorative shrimp with the appearance of reverse applique, but the composition wanted more, more. His plate should be brimming with shrimp.

Kirk Johnson

Prince came back home in May 2017 to Chicago, a city that had shaped him, growing up. He ate in a neighborhood that had fundamentally changed in the twenty-four years he’d been gone, at a restaurant that hadn’t existed when a wrongful conviction in the early 1990s took his life off the rails.

Little Goat Diner, which opened in 2012 in Chicago’s West Loop neighborhood, deliberately and enthusiastically throws tradition out the window with an exotic mashup of cultures and cuisines. A dish called “This Little Piggy Went to China” features sunny-side up eggs with Sichuan sausages on a scallion cheddar biscuit; “Bull’s Eye French Toast” is served with crispy chicken. The Asian-fusion burrito comes wrapped not in a tortilla but in Indian flatbread.

Three miles southwest of the restaurant, in late August 1991, a thirty-seven- year-old man named Edward Porter was shot and killed near the intersection of South Francisco Avenue and West Flournoy Street. It’s an easy stroll from the diner in fine weather. But worlds are contained in that walk. Much of the West Loop was, for decades, an uneasy borderland between the rough district of rescue missions, warehouses, and dive bars to the west and the glossy glow of Michigan Avenue and the Magnificent Mile to the east. The area was transformed during Prince’s years away, as the old Chicago and the new were stitched together.

From Little Goat a person heading southwest might wander into Skinner or Union Parks along the way, or push up north for a detour onto the campus of Malcolm X College. After crossing under Interstate 290, he might find the sidewalks crowded, depending on the time of day, with employees out to lunch or coming to or from work in their blue scrubs at the cluster of hospitals in the Illinois Medical District—Rush University Medical Center, The Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, or John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital.

History stretches out in every direction. Going east from the restaurant it’s less than half a mile to the site of one of the signal events of the American labor movement, Haymarket Square, where workers rose up in 1886 to fight for better conditions and hours in the city’s factories and slaughterhouses and to protest police violence. Haymarket became a symbol of labor-conscious Chicago, a rallying cry for unionization and workers’ rights—but also a historical crime story in its own right as questions swirled for decades about who threw a bomb that day and who was chosen for punishment.

A ten-minute walk in the other direction takes you to Harpo Studios, the entertainment complex created by Oprah Winfrey. Winfrey’s project was just gathering steam in the early 1990s, still an island in a tough neighborhood, only starting to build the momentum that would lead to new residential and commercial life in the area, and to the establishment of restaurants like Little Goat.

Prince was nineteen at the time of the murder. He came to the police’s attention after an anonymous caller put him at the scene of the crime, and was then, he said, coerced into a false confession. At the trial, the interrogating detective denied committing physical abuse to extract a confession, and the judge allowed the statement into evidence. With no eyewitnesses, Prince’s confession became the heart of the prosecution’s case, and he was convicted and sentenced to sixty years in prison.

Over the next two decades, through an unsuccessful appeal for a new trial that Prince filed himself from prison, through years he could never get back, the city he’d known evolved, shifted, and grew. The anonymous caller, meanwhile, had been found—and had admitted to making the whole thing up, angry at Prince over a girl. He’d just wanted to get his rival into some trouble, he said, and hadn’t imagined his call would lead to so much destruction.

Every place in the world has a story, and every person’s journey through those places can change the path for those who follow. Mistakes, triumphs, betrayals, and risky ventures combine to create the fabric of a city that breathes and lives. And then a man sits down, come from a long way, to eat shrimp and grits. In the act of taking a seat, Prince once again became a citizen of the world.

Julie Green (1961–2021) was a professor of art at Oregon State University. Her work has been featured in thirty-two exhibitions in the United States and abroad, and in publications such as the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Ceramics Monthly, and Gastronomica.

Kirk Johnson worked at the New York Times for 38 years, including 15 years as a national correspondent covering the American West. In 2001, he was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize for the Times’multi- part series, “How Race is Lived in America.”