By Ed Simon

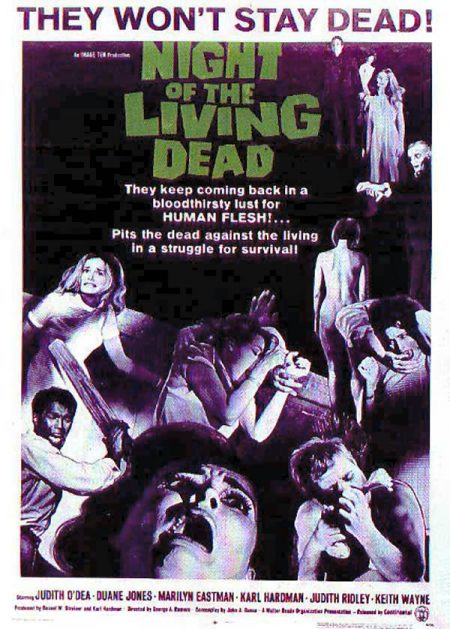

Before its premier in 1968, there had arguably been nothing like Pittsburgh director George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. Retrospectives for Romero, who died last week at the age of 77, will undoubtedly include that iconic opening scene in the country graveyard, where actress Judith O’Dea was teased by her brother—“They’re coming to get you Barbara!”—shortly before the resurrected dead did precisely that. What followed were 96 minutes of a small cast of survivors huddled together in a rural farmhouse as the dead pushed relentlessly at the windows, doors and boards of the dwelling, without conscience or consciousness—only a deep, unceasing, cannibalistic hunger.

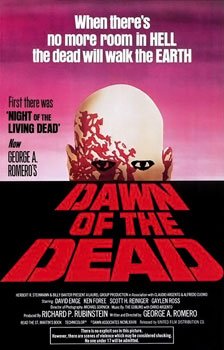

In this horrifying, gruesome, profane, satirical horror flick with a distinctly progressive social conscience, the director reinvented an entire cinematic genre, and gave us what is perhaps the first distinctly American monster. Before Romero, the zombie was a type of voodoo Caribbean homunculus, a product of alchemy and magic. With Night of the Living Dead, Romero removed the zombie mythos from these origins, which had assumed a sort of magical intention, and placed the new zombie in a completely nihilistic (and thus all the more horrifying) reality. Romero’s was a vision owed not to Edgar Allen Poe and his gothic sensibility, but rather the amoral void of H.P. Lovecraft’s Weird Tales—“When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.”

Night of the Living Dead theatrical poster. Public domain.

Pittsburgh was the city that incubated Romero’s vision. A Cuban kid from the Bronx, Romero made Pittsburgh his own. A graduate of Carnegie Mellon University, Romero was apocryphally inspired to go into the gore business after filming a segment for Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood in which the beloved children’s show host undergoes a tonsillectomy. Fred Rogers was, of course, a Pittsburgh institution. George Romero would become one too, with the first three films in his Dead franchise—Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead—all shot in western Pennsylvania. And though the rest of the series was filmed in Canada, each one either took place in Pittsburgh or had characters from the region. Other films directed by Romero, such as The Crazies (1973) and The Dark Half (1993), a Stephen King adaptation, were filmed in western Pennsylvania—Evans City and Washington, respectively. And his underrated New Wave horror masterpiece Martin (1978) takes place primarily in Braddock, just up the Monongahela River from Pittsburgh.

From Fred Rogers’ throat surgery, Romero would play a central role in the inauguration of Pittsburgh’s vibrant film industry. Night of the Living Dead had an initial budget of $6,500 with special effects involving, among other methods, the use of chocolate syrup as a surrogate for blood in the black-and-white movie. From these modest beginnings, the region would see a veritable movie boom and the production of classics like The Deer Hunter (1978), Groundhog Day (1993), The Dark Knight Rises (2012) and of course The Silence of the Lambs (1991), perhaps one of the few horror movies to rival Romero’s—and one in which Romero has a cameo, as a cop guarding Hannibal Lecter.

Romero’s incredible success was helped along by the Mozart of special effects makeup, Tom Savini of Monessen, Pennsylvania, who brought his horrific experiences as a war photographer in Vietnam to bear in the simulation of stunningly realistic blood and guts. As a team, they were masters of gory schlock at its artistic finest (I mean that as a compliment). What Romero offered to a horror-movie-obsessed teenager living in pre-hipster Pittsburgh was the opportunity to see the dark humor and sensibility of the city presented on screen for a national audience. From the running list of western Pennsylvania locations that scrolled at the bottom of the newscast in Night of the Living Dead, to the Yinzer accent of local weatherman William “Chilly Billy” Cardille (who had a cameo as himself), the Dead franchise was Pittsburgh through-and-through.

[blocktext align=”right”]If the zombie is simultaneously a metaphor for nihilistic capitalism and apocalyptic collapse, then Pittsburgh is an appropriate place for Romero to envision that particular monster.[/blocktext]Romero’s best work has a particularly Pittsburgh sensibility. Take the aforementioned Martin, Romero’s first collaboration with Savini (and the director’s favorite of his own films). An underappreciated masterpiece, Martin explores the dinginess of Pittsburgh right before the collapse of the steel industry, and is intimately attuned to the almost Old World superstitious rhythms of the region. Martin follows the arrival of its titular character, who believes himself to be a vampire, in Pittsburgh, where he is to be lodged by his Lithuanian Catholic granduncle Tateh Cuda. (not for nothing, Romero’s mother was Lithuanian.) Cuda agrees that his nephew is a vampire, and sees it as his family responsibility to allow Martin to room with him, and as his religious responsibility to prevent the vampire from feeding. Cuda is, of course, unsuccessful in that later task.

This “vampire” is a serial rapist who stalks his victims through the midnight streets of Pittsburgh, drugs them by syringe, and drinks their blood. Sometimes he calls into a local advice DJ under the name “the Count.” John Amplas’s brilliant, dead-eyed performance renders the metaphysical world of Martin ambiguous—for, as the “vampire” informs the call-in listeners, “There’s no real magic… ever.” The viewers of Martin are left to speculate whether he is really a vampire, or merely a delusional sociopath. In a just world, Martin would be seen as an exemplary New Wave character sketch, rather than “just” a genre film, and it would have inspired filmmakers to reinvent the vampire in the same way that the Dead franchise reinvented the zombie.

For another example, take the underrated fourth film in the Dead franchise, Land of the Dead (2005). Set in the same universe as the original trilogy, Land of the Dead is a prescient parable for the mood in our current America. In it, Romero envisions Pittsburgh as the last surviving encampment of humans after the zombie apocalypse, the bridges of the three rivers bricked up and a series of walls blocking off the eastern boundary of the Golden Triangle, where the survivors are protected from the undead but ruled over by a sort of uber-rich feudal lord named Kaufman (played with Rumsfeldian efficacy by Dennis Hopper). In this Pittsburgh, the rich live in an imagined skyscraper, Fiddler’s Green. The rest of the people scrounge around in trash-strewn streets downtown, until an invasion by increasingly sentient zombies threatens to upend the dystopia Kaufman has created.

Dawn of the Dead theatrical poster. Public domain.

I was visiting a college girlfriend in Baltimore when I first saw the movie—my first Romero film—and instantly picked up on the distinctly Pittsburgh tells, from the obvious (the maps and skyline), to those that were inside jokes for a local audience (the zombies, like Pittsburghers at a Zambelli display, are fixated by fireworks). Manhola Dargis, in a review for the New York Times, provincially noted that Land of the Dead took place in “a city with more than a passing resemblance to Manhattan.” But I knew better. Threaded through the film are indications of Pittsburgh’s class politics and history. In Pittsburgh, seemingly everything is named “Carnegie,” “Frick,” “Mellon,” “Heinz,” or “Westinghouse.” Yet there is a constant awareness of the conflicted legacy of those robber barons who had made the city so wealthy. In Pittsburgh, you both love and hate Carnegie, Frick, Mellon, Heinz, and Westinghouse.

A lot of Pittsburghers have dwelled in that contradictory psychology, simultaneously loving and hating those old bastards whose wealth made the city. Their money was made on the backs of the people who actually lived here, yet it is also part of why the city shakily endured while large parts of the rest of the Rust Belt fell into economic disarray—like a fortified oasis in the midst of a zombie apocalypse. Perhaps no city is as identified with dead billionaires as Pittsburgh; not even Rockefeller is to New York as Carnegie is to Pittsburgh. Growing up, Pittsburghers learned what Carnegie and Frick did to the striking workers of Homestead, or the people of Johnstown, while sitting in schools named after Carnegie and Frick. It’s not for nothing that Romero’s King of Pittsburgh, Land of the Dead’s Kaufman in his luxury high-rise, shares a name with the wealthy Pittsburgh department store magnates.

***

The zombie genre is inevitably post-apocalyptic. Perhaps now, more than ever, legitimate anxiety lies at the center of our cataclysmic imaginings. Deindustrialization, economic and ecological collapse, political turmoil—the zombie tale is the embodiment of our fears of what real apocalypse could look like. As we watch the mercury in our thermometers rise every year, we must have an awareness of how much of our current environmental predicament was first inculcated in our great centers of American industry: Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, and of course Pittsburgh. If the zombie is simultaneously a metaphor for nihilistic capitalism and apocalyptic collapse, then Pittsburgh is an appropriate place for Romero to envision that particular monster.

[blocktext align=”left”]The survivors of a zombie apocalypse, whether in a Romero flick or on The Walking Dead, fashion themselves as the ultimate rugged individualists…But Romero knew those pioneers could be as cold and merciless as any zombie.[/blocktext]That, finally, is Romero’s most important contribution: the creation of America’s only original monster, our own horror archetype. Eastern Europe may have its vampires, and Great Britain Frankenstein’s monster, but the Romero zombie is an American affliction: pure American late capitalism. A 1968 Variety review of Night of the Living Dead judged the “Pittsburgh-based [film] makers” for their “unrelieved orgy of sadism.” In that orgy was the conception of necessary nightmares, of America’s great entry in the bestiary of monstrosity.

Listen to coworkers around the water cooler talking about The Walking Dead; nobody assumes they’d be the walking corpse. It’s been observed that the zombie (unlike the sophisticated, romantic, sexy vampire) is a variety of monster that nobody would fantasize about becoming. Better to be the survivor of the zombie apocalypse, flattering ourselves that we would make it through the collapse of civilization. But in The Walking Dead, as in Romero’s films, the true monster is never the zombie—as any fan of the genre knows, its central lesson is that one needs to fear the living more than the dead.

Yes, of course the monsters are us, they’ve always been us. Zombies and survivors are but men and women simply pushed to their ultimate conclusion. In Romero’s vision, they’re not just men and women, but specifically American men and women. Romero understood the malignancies in the American spirit, our inclinations to violence and consumption. In the relentlessly cynical and pessimistic apocalyptic logic of the Romero zombie flick lies that strange, terrifying, and barely-hidden fact about the American people: we have a deep and abiding wish to be able to kill our neighbors with impunity, without sanction or regret. In its mindless and ceaseless appetite, the Romero zombie (which is the accepted template in the genre, from 2002’s 28 Days Later to The Walking Dead) is the decomposing Id of the collective American citizenry.

The survivors of a zombie apocalypse, whether in a Romero flick or on The Walking Dead, fashion themselves as the ultimate rugged individualists, frontiersman fighting off unseen enemies in a land they view as promised for them. But Romero knew those pioneers could be as cold and merciless as any zombie. In Night of the Living Dead, Ben, the courageous African-American hero (masterfully played by Duane Jones), is intentionally shot and killed by a posse of militiamen ostensibly clearing the woods of the undead. In this one scene, made in that sweltering year of assassinations, the violent, greedy history of America, and its racist consequences, is laid literally and terrifyingly bare. For as Romero knew, the horror of the zombie is not what they do to us, but rather what they reveal about us.

_____

Public Domain cover image via Wikimedia.

Ed Simon is a senior editor at The Marginalia Review of Books, a channel of The Los Angeles Review of Books. His work has appeared in, among other places, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Salon, Nautilus, Aeon, LitHub, and Belt Magazine. He holds a PhD in English from Lehigh University, and can be followed at his website, or on Twitter @WithEdSimon.