David Exelby was scrolling through Reddit when he came across a mysterious post. This guy had stumbled on a ghost town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The problem was no one could find it. David and producer Max Howard go looking.

By Maxwell Howard

The following transcript is from an episode of Points North, a narrative podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. Listen to more episodes at pointsnorthpodcast.org.

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: Earlier this year, David Exelby was scrolling through Reddit when he came across a mystery.

DAVID EXELBY: I ended up finding this guy’s comment on someone else’s posts … He just said, one time while bear hunting out in the base of the Keweenaw Peninsula in the U.P., he and his friends stumbled across a ghost town.

WANSCHURA: The hunter said it looked like the town had been evacuated quickly.

EXELBY: It looked like all the belongings were left inside of some of these structures. He said it looked like maybe around the 1930s or 40s. But he wasn’t sure.

WANSCHURA: David wanted to find this town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, but there was only one real clue – a sign the guy thought was the name of the town.

EXELBY: He couldn’t remember it was Pearline… Pearlised… something along those lines, but it had “pearl” in it. So, Pearline, or Pearlised.

WANSCHURA: So, Pearline maybe. Some other people thought it might be called Pauline. Somewhere on the Keweenaw Peninsula, probably near a town called Twin Lakes. David searched online for the town but couldn’t find anything – all of which got him thinking…

EXELBY: Like, how quickly history can get lost? It’s the idea that what if there was this real quick established town – this whole piece of history – these stories, these people, all this stuff – and we don’t have any evidence of them even being there anymore? No paper trail, no nothing.

WANSCHURA: Could this really happen? Could a town called Pearline really disappear?

WANSCHURA: This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura. Today on the show, we take a road trip to the Keweenaw Peninsula with David and independent producer Max Howard, to look for a lost town. Maybe it’s a wild goose chase, but maybe, just maybe, they’ll find what they’re looking for. That’s right after this.

(sponsor message)

MAX HOWARD, BYLINE: David Exelby and I are old friends. I’m talking like back-to-the-second-grade. We’re both big talkers. Novels, politics, something stupid or funny – we’ll talk about whatever. We also like history.

EXELBY: I love Michigan history especially like more obscure, more just forgotten stuff that we don’t know about as much.

HOWARD: When David told me about this mysterious town Pearline, I was hooked. And since we couldn’t find anything about Pearline online, we set out on a road trip to try and find it for ourselves. For David, it felt like a video game.

EXELBY: And once you get playing enough, it’s not about the missions anymore. It’s about like the fun little easter eggs you can find within the map. And it sounds so funny. But like, this is like a real world easter egg to me.

(sound of driving)

HOWARD: We set out early, driving along Lake Superior.

HOWARD: It’s been so foggy.

EXELBY: Yeah.

HOWARD: And like it’s kind of a perfect mystery, you know, like Mystery Inc. weather.

EXELBY: Yes.

HOWARD: I feel like we really are going into, like, a Scooby Doo episode right here like the fog is coming down, the sun is red.

EXELBY: Yeah.

HOWARD: It’s just coming over. The plan was simple – even if we were working out some of the kinks along the way. First, we would talk to the locals and see if anyone had ever heard of Pearline. Houghton was an obvious place to stop. It’s the biggest city on the peninsula with a large student population from Michigan Technological University.

I don’t want to talk to– what student is going to know about– maybe we shouldn’t stop here because it’s probably a bunch of kids.

We had to find someone local who had a deep connection and knowledge of the peninsula.

Maybe like a bar up here or something?

EXELBY: Yeah, we’re not even in the downtown spot yet.

HOWARD: But yeah, we could stop at a bar, we could even go into like a grocery store and just ask people.

EXELBY: That’s a good idea.

HOWARD: Just stop them.

We pass through Houghton. And as we got closer to where the Reddit poster said he was bear hunting, we stop to ask more and more people.

Hey, how are ya? Hey, I have a question for you.

LOCAL #1: I might have an answer.

HOWARD: Have you ever heard of a town called Pauline or Pearline?

LOCAL #1: No. Let’s Google it.

HOWARD: I’ve Googled it…

We stopped people on the side of the road, clerks behind gas station counters –

(door chime ringing)

A pair of teenage boys eating their lunch of BBQ chips and Gatorade in a party store. Most people thought we were looking for a different town an hour or so south.

It’s called Pearline or Pauline. Have you ever heard of that?

LOCAL #2: Never heard of it.

HOWARD: Never heard of anything like that?

LOCAL #2: No.

HOWARD: Nothing rings a bell? Nothing at all? Okay, well thanks.

LOCAL #3: Uh, Paulding?

HOWARD: That’s what everyone keeps saying – Paulding.

LOCAL #3: No, well that’s the only one I’ve heard of. I’ve only ever heard of Paulding.

HOWARD: But there are abandoned towns around here – or there’s like mine shafts and stuff like that?

LOCAL #3: Oh yeah, mine shafts, but I’m not sure where any are.

HOWARD: Hmmm, okay. Well hey, thank you.

We weren’t looking for Paulding. I thought this might happen though, which is why I had reached out to Emily Schwiebert, before we went on our road trip. Emily is an archivist at Michigan Tech and was helping me try and locate Pearline.

HOWARD: Hi, Emily.

EMILY SCHWIEBERT: Max and David?

HOWARD: Yes. How are you?

SCHWIEBERT: Good. How are you guys?

HOWARD: Good. It’s nice to meet you.

SCHWIEBERT: Glad you guys found it.

HOWARD: Emily and another one of her colleagues had been introducing me to people they thought could help. They were sending me annotated maps with little known historical sites and even an article about Pearline, except they called it Pauline, but it was clearly the same town. When the article popped up in my email, my heart sank. I thought maybe our mystery had already been solved. According to the article, a man was at a place called Jake’s Bar near where we thought Pearline was. The bartender, who is also called Jake, told the man he knew how to find Pauline. I had to make a call.

(phone ringing)

VERNON HARLOCK: Hello, Vern speaking.

HOWARD: Hi, my name is Max Howard. How are you doing?

HARLOCK: I’m good how are you?

HOWARD: Good. Hey, I’ve got kind of a funny question. So does Jake still own the bar?

HARLOCK: No, I own the bar. It’s gone through a couple different people since Jake’s owned the bar.

HOWARD: So, I posed the question to Vernon Harlock. Does he know where Pauline is?

HARLOCK: You know, I’ve heard that story. I think it’s north of Winona. Winona is just south of Jake’s. I’ve never ventured there – tried finding it – anything like that.

HOWARD: Okay.

Vern didn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know. We already knew that Pearline was somewhere near some town called Winona. So, we still had a mystery. Emily had trouble finding Pearline too, but knowing we were driving up, invited us to take a tour of a ghost town she had her own connection to – Winona – the same town that Vern mentioned.

(sounds of touring the town)

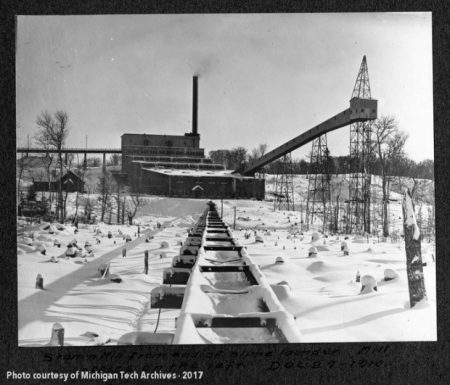

Winona stamp mill from end of slime launder. The mill office on the left. December 27, 1910. (credit: MTU Archives)

SCHWIEBERT: I will say one thing that you can kinda see when you’re up by the school here that I really love about UP towns is that the roads are pretty much what they say on the label. So, we have the Old Post Office Road – do you know where the Old Post Office Road is?

HOWARD: Emily, David and I walk down a dirt road that loops through the woods. Every quarter mile or so we pass a home far back in a field. This used to be a copper mining town of twelve hundred, but the only sign that there was anything – besides sparsely placed homes – is a schoolhouse, which I have to say seems comically large. There are probably more rooms than there are students, I’d guess.

SCHWIEBERT: It’s still in use. Last I heard they had maybe six students in 2019.

HOWARD. Well, cause we were coming in here and we saw the population was 19. So, we’re like, ‘This is a pretty big schoolhouse.’

HOWARD: So, would you call this– I mean, I guess would you call Winona a ghost town or what would you call it?

SCHWIEBERT: Someone once called it an almost ghost town and I feel like that’s a pretty good descriptor of it. You know, it’s not – it’s not what it was. Twenty people can’t compare it to 1,200 people.

HOWARD: Emily’s family history goes way back in Winona. Her dad grew up here, and his dad grew up here too. They stayed in Winona even in hard times, finding ways to make enough money to stay in their hometown and support their family – like when Emily’s widowed great-grandmother turned to moonshining.

HOWARD: Well, it’s funny just to even call this a town because it just – it kind of looks like a road. There’s a couple houses on it.

SCHWIEBERT: Right. Yeah.

HOWARD: It doesn’t seem like a ghost town – not like the kind you’d imagine where all the buildings on main street are still standing and a gentle breeze swings the shutters on an abandoned home. No, instead, it seems like nothing has ever even been here. But then, Emily leads us into the woods.

SCHWIEBERT: This way.

HOWARD: Okay.

SCHWIEBERT: This is where we’re going to be kind of going into the grassy area if you need bug spray, I have it.

HOWARD: I think I’m good.

We go into the forest on a half hour hike on no discernable path. Sticks and branches block our path, knocking around my microphone.

Um, so, well I’ll ask you when I’m untangled from all this– get out of here in a second.

(sound of hiking)

We hike until Emily stops us at one of Winona’s two mines.

(arriving at the mine)

The sprawling ruin of the town of Winona in the Keweenaw Peninsula. (credit: nailhed.com)

The mine’s mouth goes straight down into the ground and it’s incredibly dark. On top of that, the mine is surrounded by a grove of trees – some of the trees beginning to creep into the inner edges of the mine. There’s a fence around it, but – absent that marker – I wouldn’t have seen the mine at all. That is until I’d have fallen in.

SCHWIEBERT: I think it’s a testament to people trying to exploit the earth and the earth reclaiming itself when the people are no longer working on it.

HOWARD: Yeah, you can leave this giant hole here. We’ll just grow over it.

EXELBY: Yeah.

SCHWIEBERT: Exactly. Trees don’t care.

HOWARD: Just a little ways into our hike, I’m completely lost. If Emily left me alone, there is no way I’d be able to find my way back.

Can you– does this even connect to a road anymore? I mean, there’s no other way to get here besides the way we just went?

SCHWIEBERT: Yeah, you’re not getting here unless you have an ATV that’s going to go off roading. But there’s no way you could really drive up here without that kind of vehicle. You’re just walking.

EXELBY: There’s no direct trail leading to this.

SCHWIEBERT: Exactly. Yeah, this isn’t something that people are encouraging you to discover.

HOWARD: From there, we follow a tall ridgeline miles into the woods. This is where they used to cart materials to the stamp mill, Emily tells us. Finally, the trees begin to clear, and we come upon the real ghost town of Winona.

Ruins of the ghost town of Winona in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. (credit: nailhed.com)

SCHWIEBERT: So, you can kind of see where some of those stamp heads were set up.

HOWARD: Wow. Oh my gosh, this is huge. Yeah.

EXELBY: You gotta be kidding me.

SCHWIEBERT: You just would never know when you’re driving down the road and Winona, this is here. You wouldn’t know when you’re driving down the highway that Winona’s here if not for the sign in a lot of cases.

HOWARD: Yeah, well it’s just completely overtaken? It’s this massive structure. And there’s just, I don’t even understand how it was here at some point.

David and I look down a hill at the ruined structure of the Winona Stamping Mill – a mill that crushed rocks from the nearby mines. We stand on concrete at the highest point of the mill, then about 50 feet down is another concrete level, and then another. Concrete spires dot the landscape – what used to prop up machinery.

Yeah, this truly does feel like I stumbled onto like, I mean, Machu Picchu or something, you know?

SCHWIEBERT: Exactly. It’s industrial Machu Picchu. Yeah, yeah. I’ve heard a few people actually use that term specifically to describe the stamp mill and others in the woods.

HOWARD: And really, the stamp mill is just a small part of what used to be Winona. Deeper in the woods are the relics of an old railroad, a large company store and the abandoned homes of Winona’s past residents.

Emily Schwiebert and Max Howard looking into the King Philip Mine in Winona. (credit: David Exelby)

It’s just interesting you never think about– I mean, with all these towns we’ve been talking about– I mean, I never think of a town as a place that appears then disappears so quickly.

SCHWIEBERT: Yeah.

HOWARD: You know? I mean, is it as simple as just saying it’s just the nature of the resources that are around here? They’ve plumbed the mine. They’ve clear-cut the area. Is it as simple as that? Or do you think there’s a little more to it?

SCHWIEBERT: I think there’s more to it. You know, towns come and go because people need them to be there, basically. So sometimes it’s the resources and when the resources are gone, people do leave. And sometimes it’s just this place becomes something to you, and the town sticks around because of that. I don’t know if that really answers the question. … There’s just something about a place sometimes that really grabs ahold of people and says, ‘Put down your roots here.’

Some of the ruins of Winona, a half-forgotten ghost town in the Keweenaw Peninsula. (credit: nailhed.com)

HOWARD: Seeing Winona, I feel like my question – as to whether a town could really disappear – was kind of answered. Sure, Winona is on the map, you can punch it into your navigation system, but to really know the town, what lies in the woods past the schoolhouse, someone has to show you how to get there – like Emily’s dad showed her and Emily showed us. If Winona, or a part of its history disappeared into the woods, I think Pearline could too. David and I say goodbye to Emily and head back out on the road. We drive around talking to people at rest stops and party stores – still unable to find anyone who has ever even heard of Pearline.

EXELBY: Are you still recording?

HOWARD: Mhmmm. I’m just letting it roll.

We talk about what we think this weekend meant –

Well, and it’s like, even if Pearline isn’t real, even if this is just some drunken ramblings of Reddit posters, Reddit commenter – certainly if it doesn’t – Pearline doesn’t exist in name, it exists as an idea. There are forgotten towns, there are forgotten spaces, there are forgotten histories.

EXELBY: Yeah.

David Exelby takes a selfie with Max Howard and Emily Schwiebert overlooking the Winona Stamping Mill in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. (credit: David Exelby)

HOWARD: David had reached out and spoken to the original poster on Reddit in the weeks leading up to our road trip but was ghosted as our trip neared. If Pearline existed, its memories were certainly growing weaker — whittled down to a few comments on the internet, a bartender recounting another bartender’s story, and a podcast that never finds the town in question. We didn’t find Pearline — maybe it doesn’t exist — but plenty of other ghost towns in the Great Lakes region do, including Winona – a half-forgotten town.