By John G. Rodwan, Jr.

Perhaps no writer and city are as tightly bound as James Joyce and Dublin, but when I first read a character in Joyce’s story “A Little Cloud” express ambivalent relief on returning to “dear dirty Dublin,” I immediately thought the phrase could be modified, with alliteration left intact, to describe perfectly the city where I spent my youth and to which I returned in middle age. Having lived many years in Detroit and quite a few years elsewhere, I’ve known plenty of people who could immediately see how “dirty” applies to it but can’t comprehend what could possibly make it “dear.” For me, like the journalist Ignatius Gallagher in Dubliners, when it comes to my town, the two adjectives can’t be separated, even by a comma.

[blocktext align=”left”]Many books about Detroit do not attempt to be anywhere near all-encompassing, letting certain parts, dilapidated buildings, say, stand for the whole. [/blocktext]Though he lived the majority of his years, and did most of the work for which he’s known, while living elsewhere, Joyce never stopped thinking of himself as a Dubliner. He considered the city his spiritual home. “For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world,” he explained. “In the particular is contained the universal.” He strived to present the particulars precisely. In 1921, while living in Paris and nearing completion of Ulysses, he wrote to an aunt back in Ireland to inquire if it would be possible for an “ordinary person” (like his character Leopold Bloom) “to climb over the railings of no 7 Eccles street, either from the path or the steps, lower himself from the lowest part of the railings till his feet are within 2 feet or 3 from the ground and drop unhurt.” Because of such extremes of exactitude, Joyce claimed that historians a century after the novel’s appearance could recreate the city using Ulysses alone.

Call me crazy for questioning one of the world’s most celebrated authors, but I have my doubts about all this. No matter how finely detailed and imaginatively comprehensive a book might be, it can never include everything about any city. What Ulysses recreates, magnificently, is how Dublin looked, smelled and sounded to James Joyce. I’d hazard that some other early twentieth century Dubliner reading Ulysses might recognize some of the businesses named, modes of speech reproduced, and buildings described but still not regard Joyce’s Dublin as his. Far from faulting Joyce for his effort to get everything in, I admire his ambition. Many books about Detroit do not attempt to be anywhere near all-encompassing, letting certain parts, dilapidated buildings, say, stand for the whole. In their quest for the universal, they take Detroit’s troubles as symbolic of something or other and lose sight of its distinctive particularities.

The alternative is to acknowledge that a piece of writing or a collection of images offers a personal vision: Here’s what this place looks like to me. Here are my memories and impressions. Someone else might look at this differently and have seen things I never saw, but this is my perspective and this is what I know.

Even then, though, with Detroit, certain things—and not just those collapsing structures—are unavoidable.

*****

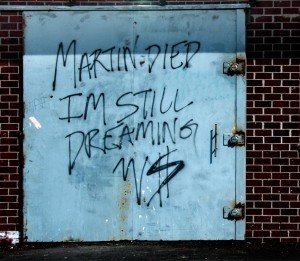

Race and income define Detroit’s reality as much as any rivers, buildings or streets establish its geography. From where an overpass crests above Eight Mile Road—the recognized dividing line between the poor, black city and the prosperous, white suburbs—Woodward Avenue affords a panoramic view. The sharp contrast between the urban and the suburban sides speaks loudly about what, far more than a mere thoroughfare, separates them. Driving on Woodward not long after I bought a house a couple miles in from the city’s firmly etched northern border, I noticed, spray painted on the boarded-up windows of a storefront next to a vacant lot, the quip “Martin died and I’m still dreaming.” (Although the “I Have a Dream” speech became identified with the August 1963 March on Washington, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered a version of it months earlier in Detroit.) Even though just a little farther into the city lies Palmer Woods, a neighborhood of large, august homes impressive by any standard, and some other relatively stable residential areas (including one where I grew up and another into which I later settled), a glance to one side of the street and then to the other provides undeniable evidence of disparate experiences, of dreams not so much deferred as denied.

[blocktext align=”left”]…it makes no sense to think all black people think and behave the same way or that all white people think and behave the same way, no matter how much folks from inside and outside the city insisted so. [/blocktext]If metro Detroiters (those in and around Detroit proper) seem to cling obsessively to racial categories (and they do) and the city routinely gets tagged as segregated (and it does), then that goes to show how generalities about a place can belie individual lived experiences of it. Growing up in Detroit, I made friends with people who fit into various racial classifications—or didn’t fit neatly into any of them—and we never thought such things were reasons to like or to dislike a person. It’s not that we were so naïve that we didn’t know how much meaning people attached to skin color. No one could live simultaneously in Ronald Reagan’s America, where a creaky conservative president seemed oblivious or indifferent to the kinds of problems Detroiters faced, and Coleman Young’s Detroit, where a liberal fire-breather mayor loudly accused racists for the city’s woes, without realizing that attitudes about race were not mere abstractions. People’s beliefs, whether idiotic or enlightened, and the decisions they made based on those beliefs had real consequences, consequences plainly on view from that Eight Mile overpass or the remnants of the Birwood Wall, a six-foot-tall concrete barrier built in the 1940s to keep a white middle-class neighborhood in northwest Detroit firmly separated from any black families who moved in nearby. Reverend King’s birthday may have become a holiday while Reagan was in office, but no one mistakes the Republican ex-thespian for a tireless advocate for the advancement of black people. Young’s ascendancy to the leadership of a city of Detroit’s size was a significant historical step, but the civil rights warrior didn’t exactly encourage racial harmony. Neither of those men truly looked past skin color to judge individuals’ characters.

Such divisiveness persists. One public figure, a black man contemplating a run for mayor, started 2013 by claiming his potential rival, a white man who’d moved from a suburb to Palmer Woods, couldn’t understand “the common experiences Detroiters have.” The former said, “It’s our Detroit, and we’re going to keep it for Detroiters,” asserting that “Palmer Woods is not Detroit.” While he subsequently backed away from the remarks and acknowledged that the neighborhood in question was indeed situated within the city limits, he’d already voiced unanswerable objections to his possible opponent: that some people can legitimately represent Detroiters while others cannot, that living in Detroit alone does not make one a Detroiter, that to know real Detroit one must look to the dirt, only and always to the dirt.

[blocktext align=”left”]After I moved back in 2011, friends from elsewhere eagerly wanted to come and tour the supposedly emptied out post-industrial wasteland. [/blocktext]Ignorance, I found, didn’t impede enough people from passing judgment on Detroit. My parents may have gone against the wind of white flight and moved into Detroit soon after the 1967 riots, but not a small number of their suburban counterparts taught their children to fear Detroit and told them never to venture south of Eight Mile. (I suspect these children grew up to become the adults who, when they moved elsewhere, said they were from Detroit when they really came from Birmingham, Farmington Hills, Royal Oak, or some other sedate suburb. I understood a practical reason for these claims: people who never heard of the city’s close satellites would have heard of Detroit. Yet I often sensed a desire to project urban authenticity via association with Detroit’s notorious grit, and this was regularly confirmed when I said I came from Detroit and the pretenders simultaneously expressed surprise that I meant the city itself and embarrassment because I knew the true distance between their real hometowns and mine.) Even before I went to a monochromatic college in the western part of Michigan and learned that, by moving in polychromatic circles during my youth and adolescence, I’d had an atypical time in an atypical town, I understood the code: parents inculcating anxiety about Detroit were scared of black people. They might have been willing to work in a downtown office, and even to attend hockey games at an arena named (at Young’s insistence) after the great black boxer Joe Louis, but they didn’t want to live among black people, and, intentionally or not, they handed their faults along to their sheltered offspring.

Still, facts are facts, and certain facts about Detroit give cause for wariness. The city regularly charts unemployment and poverty rates that tower above the national averages. It consistently notches one of the county’s highest murder rates. It has very low rates of high school graduation and startlingly high levels of illiteracy. Numerical shenanigans invariably taint news coverage about such things. When crime statistics for 2012 were released, for instance, some reports flagged the 386 criminal homicides, which worked out to about 54 per 100,000 residents, as the highest in almost twenty years. If journalists looked back twenty five years, however, they would have found that both the total number and the rate had declined. Nonetheless, this much is indisputable: Detroit earned its reputation as a terribly poor, exceptionally violent city with much to inhibit a return to prosperity.

Here’s another fact: growing up in Detroit when I did among the people I knew taught me that it makes no sense to think all black people think and behave the same way or that all white people think and behave the same way, no matter how much folks from inside and outside the city insisted so. The city’s story is more complicated and interesting than that. So are its people.

*****

[blocktext align=”left”]I always write about Detroit, because if I can get to the heart of my dear dirty Detroit I can get to the heart of one of the most fascinating, singular cities in the world, but I do so fully conscious that there’s always more to the story—and more than one story.[/blocktext]After I moved back in 2011, friends from elsewhere eagerly wanted to come and tour the supposedly emptied out post-industrial wasteland. They hoped to observe up close the infamous ruins they’d seen in photographs: the windowless train station that hinted at an end to forward motion, the long-inactive automobile plants that testified to industrial demise, the stores and houses in which trees and bushes grew, suggesting reclamation by nature and the transitory nature of all human beings’ works. In witnessing these emblems of misery, these monuments to failure, these icons of decay, they expected both aesthetic and existential experiences. Or so it seemed to me, and I found it distasteful. I also understood how residents could regard tourists snapping shots of tumbledown buildings as, if not actually exploiting a suffering black city, callously disregarding the sensitivities of those who live with such sights day after day.

So, without trying to conceal the dirty bits —which, frankly, would have been impossible—I tried to show them at least some of what makes Detroit dear. That was the ramshackle old Fisher Body plant, but this is the stately pile Charles Fisher had built on Boston Boulevard back in the ’20s, and Berry Gordy’s palatial former digs are just up the street here. We can go by the sprawling remains of the Packard plant if you want, but first let’s stop in the Detroit Institute of Arts. Fine, gawk at the damn train station if you must, but the Guardian Building, that Art Deco gem, gets equal time. Before you take this neighborhood—where every other house is boarded up or burned out—as representative, let me show you Tyree Guyton’s effort to recast such an area along Heidelberg Street as a public art project, where children traipse among the painted shoes and polka dots, and, yes, the mansions built for automobile industry executives over in Palmer Woods. Okay, you’ve seen stretches where liquor stores and almost no other businesses operate; now you need to see the sheds teeming with shoppers at the Eastern Market on Saturday morning.

*****

I always write about Detroit, because if I can get to the heart of my dear dirty Detroit I can get to the heart of one of the most fascinating, singular cities in the world, but I do so fully conscious that there’s always more to the story—and more than one story.

Just as not every picture of naked people counts as pornography, not every image of modern-day urban ruins arises from debased motives. Massive factories that once harnessed so much energy and channeled so much labor into so many machines do look gloomily suggestive when they fall quiet and steadily erode. An ugly beauty can be glimpsed in the architectural details and careful craftsmanship that endure in corners of buildings like Michigan Central Station even as they rot and turn to rubble. Signs of life—a sodden book, a cobwebbed candlestick, a frozen clock, a torn poster on a flaking wall—do resonate and haunt when left behind in poignant vacancy. It does remain worthwhile to look at the Birwood Wall, not only for its mute testimony to perverse thinking put plainly into practice but also for the artistry of the bright murals that remade it as something other than scandalous. The houses where nobody lives, and where no one will ever live again – with roofs caving in, the windows smashed, the gutters falling off and the pipes stripped out for scrap—do tell sad silent stories.

Those stories should not be mistaken for the whole story, which would have to include children cavorting in the fountain on the RiverWalk as well as children walking past those gutted homes on their way to schools that fail them, the occupied houses with the proudly maintained lawns as well as the empty houses with grass cut by the people who live next door, the vacant lots converted to community gardens or small urban farms, as well as the ones strewn with broken glass, the people who maintain long-established businesses or open new ones even as others disappear from the very same block, the activists committed to doing good as well as the troubled souls who don’t know what they’re doing, the innovative artists and musicians as well as the unemployed autoworkers and corrupt politicians, the frequent unplanned meetings with friends and neighbors that can make Detroit feel like a small town as well as the eerie expanses of emptiness that can make the city feel too big.

This much is obvious: our unique experience of a place cannot be duplicated. People living in the same place can and do have wholly dissimilar experiences, so much so that in very real ways my Detroit and yours are not the same place, despite the shared longitude, latitude, and landmarks.

John G. Rodwan, Jr., is author of the essay collections Holidays & Other Disasters (Humanist Press, 2013) and Fighters & Writers(Mongrel Empire Press, 2010) as well as the chapbook Christmas Things (Monkey Puzzle Press, 2011). His work has appeared in journals including The American Interest, Blood & Thunder, Concho River Review, Cream City Review, Midwestern Gothic, Jazz Research Journal, Pacific Review, Pea River Journal, Pudding Magazine: The Journal of Applied Poetry, San Pedro River Review, Spot Literary Magazine, Thin Air and Trickster. He is a contributor to A Detroit Anthology. He lives in Detroit.

As someone who grew up in Detroit but is no longer a resident, I always try to say “Ypsilanti” when someone asks me where I am from as I share that annoyance with people claiming Detroit when they shouldn’t. The thing is that after I tell them were I currently live, they always go “huh?” because not too many people have heard of Ypsilanti. Then I have to say that it’s 30 miles west of Detroit.

My story about growing up in Detroit is very similar to yours, not surprisingly considering. When I first moved out of the city to Ann Arbor, I encountered many of the same views of the city you did when you first left. It was very common for me to plan some activity in the city only to have one (or several) of my friends’ parents forbid them to join me on the grounds that Detroit was just too dangerous. It was extremely frustrating at the time especially since we were usually going someplace that was perfectly safe. I think people sometimes forget that even though Detroit is a city with problems and certainly has areas which are not entirely safe, there are also plenty of areas of the city where people thrive and manage to exist without murdering each other or any stray white people who might happen to venture inside the city limits.

I grew up in suburban Detroit, and when people whom I know wouldn’t be familiar with the area ask me where I’m from, I usually say “metro Detroit” or “suburban Detroit”, so as not to come off as a “pretender”. I also think, though, that it’s not necessarily wrong to expand the idea of Detroit, to some degree, to the metropolitan area. I do think that some kind of shared identity is important for the area to survive and prosper (because I don’t think you can wall off the city’s economic problems in the long term, despite the delusions of folks like L. Brooks Patterson). That said, I realize that “regionalizing” Detroit has its pitfalls and that shouldn’t erase the experiences of those who live and have lived there. But the politics of authenticity also have their drawbacks and we should be aware of those as well. Should I ever return to southeast Michigan, either to the ‘burbs or to the city, I would like to think that I could be a Detroiter. That will, however, require some considerable work on my part in remedying any faults that were passed on to me, as the author puts it.

I find the argument that people from the suburbs should be scorned for saying they are from Detroit, not just because technically they are not from the city of Detroit proper, but because t implies they somehow don’t fit in with Detroit,. Yet someone living in a larger house in Palmer Park, can claim they are from Detroit, even if living there is nothing like living in other parts of the city.

Shared identity is need. Consider a person who worked downtown, visited the museums, rotted for Detrtoits sports teams, ate at Coney Islands, drank Faygo pop, and you tell them because their house is north of 8 Mile that they are not from Detroit.