I get sentimental about places, especially forgotten ones like Monarch Park. They’re a bit of a bummer, a bit sobering, a bit sad. But I think it’s a good kind of sadness.

By Hannah Kennedy

Each summer when I was growing up in Oil City, Pennsylvania, my siblings and I looked forward to Youth Field Day in July, when kids from the community would spend a whole Saturday in the woods, learning the skills of outdoorsmanship. The event was led by the local chapter of the Izaak Walton league, helmed by grandfatherly mountain men who were tasked with passing on our Northern Appalachian traditions of resilience and self-sufficiency. The kids were joined by their parents and grandparents (in our case, Dad and Grandpa), with the goal being to take part in these activities as a family.

Our summer field days went like this – we got up early and piled into Grandpa’s green pickup truck, driving a few miles out of town down Deep Hollow Road, which carves up the space between two steep hillsides. We turned off onto a gravel driveway which wound its way through the forest, on stone bridges over the creek, and finally to a large rough clearing surrounded by thick tree cover. We joined the dozens of other kids at the main building, where we signed in, got free tee-shirts (a different color each year) and grabbed a quick breakfast of fruit and pop-tarts.

Then, the games began. The Izaak Walton grounds, officially called Waltonian Park, covered about sixty acres of land and a few buildings. A large pond sat in the middle of the grounds, as did an ancient water fountain and rusting swings and slides, and a weird stone memorial fenced off and a little overgrown. A few hundred yards away, a gun range extended down into a small valley, and trails probed into the thick forest like tendrils of a vine. It was all very rustic for sure. The main building and various pavilions had only the bare necessities and were decorated with a generous collection of taxidermied animals. The head of an albino deer mounted on one wall always seemed to bore into my soul with its eerie red eyes.

The day was broken into short increments, and each child was organized into a team based on age group. Then, each group rotated through different activities. So every field day, we had a chance to do everything – archery; fishing lure-making; target shooting with a .22, target shooting with a shotgun, and target shooting with a muzzleloader; an obstacle course; hatchet-throwing (which I was terrible at, and definitely responsible for my team losing for); canoeing on the pond, fishing on the pond (taking care to avoid the black snakes nestled in the sunny grass); interactive sessions on identifying animals and plants; and trapping (have you ever seen a bear trap up close? My tibia bones shudder even thinking about it).

While I haven’t pursued the majority of these activities in adulthood, I appreciate that this kind of event existed – an educational, interactive, fun environment for kids to learn about the outdoors, the kinds of skills one needs to survive in a rural community. This experience instilled in me a value I still hold to this day: that education is the single most powerful way to understand how the world works, to preserve a way of life, to protect from potential dangers, and to empower people for whatever comes next.

Of course, I didn’t really think about all of that as a kid. I just liked making a pretty, hot-pink fishing lure, and showing the teenage archery instructor that despite his protestations to the contrary, it is, in fact, possible to shoot a right-handed bow with one’s left hand.

It wasn’t until later, as I pursued a career in writing and discovered my deep love for the forgotten post-industrial places of my homeland, that I learned the whole context about this place. I learned that Waltonian Park was not always Waltonian Park. It was not always a remote backwoods outpost with a shooting range. Instead, it was one of the largest attractions in the surrounding region, bringing families, thrill-seekers, and parties from miles around.

This place was Monarch Park, an enormous amusement park in what is now the middle of the woods.

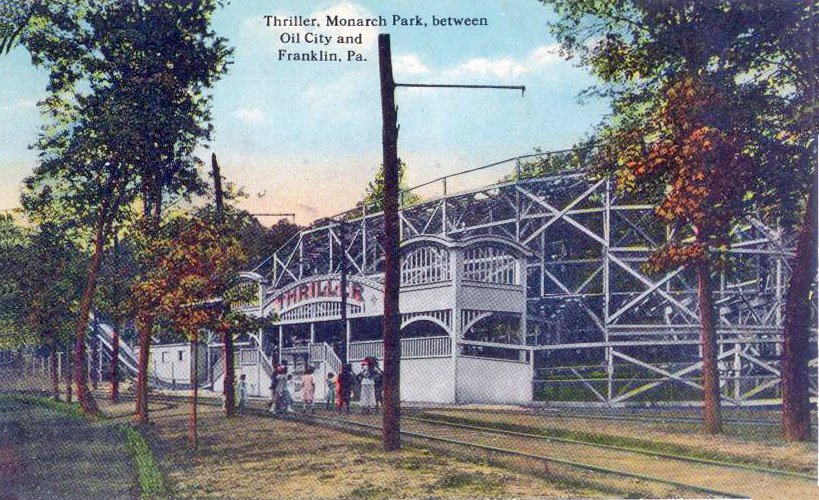

From the 1890s to the 1920s, Monarch Park operated in full swing. Featuring a merry-go-round, dance hall, bowling alleys, botanical gardens, waterfall, a Ferris wheel and rollercoaster, shopping, picnic facilities, fine dining, and more, the park saw up to 15,000 visitors on summer weekends, a number which grew up to 30,000 on holiday weekends. Situated in Venango County, Pennsylvania between the towns of Oil City and Franklin, it was just a trolley ride away for hours of fun.

At the time, this region, the Oil Region, was still the center of the oil industry. And while the frenzy of the oil boomtowns had mostly mellowed, Venango County, PA was still the place to be. And up until the end of the Roaring 20s, so was Monarch Park.

Parties of thousands gathered in the restaurant and picnic pavilion for private parties and holidays. People enjoyed dancing in the two-story dance hall, listening to music from the outdoor orchestra pit, riding on the miniature train, drinking from the natural spring fountains, idling on the playground swings and slides, testing their strength and endurance in organized races and contests, and of course, enjoying the typical amusement park diversions of Ferris wheel, carousel, and roller-coaster. At the center of the park, a 120-foot tower featuring elegant glass windows and a domed roof dazzled with electric light. The park held celebrations for holidays like Memorial Day and the Fourth of July, culminating in marvelous fireworks shows.

By the end of World War I and the onset of the 1920s, however, the popularity of the park tapered off. The 1920s brought an even greater popularity of that American mainstay: the car. People began travelling farther for vacations and holidays. By the end of the 1920s, Monarch Park folded, and the facility was sold to a few buyers before coming into the possession of the Izaak Walton League. Even though various plans were proposed to keep at least some of the attractions going, none came to fruition, and the park structures sat abandoned and derelict until eventually they were torn down or destroyed by the elements. Some buildings were dismantled, and the materials used for other projects in the community. In fact, the floorboards of the two-story dance hall were used to build three houses in the neighborhood I grew up in.

There’s something that hits me when I think about all of this: when I compare maps of the old park layout to the modern satellite images of rugged forests and creeks; especially when I consider the many extant pictures of a hundred smiling faces gathered around the playgrounds or picnic pavilion, of couples dancing in their elegant party clothes, of the band members shyly mugging the camera between sets. To the people in these photos, captured in a moment of light and movement and fun, the place they were in must have seemed so permanent, so fixed in the grand scheme of life.

What really hits me is the sheer amount of time I spent in this place—hours over entire days, over several years—with no idea of what it was. The pond I canoed and fished in is where the carousel used to be. The main building where I ate strawberry pop-tarts, while staring at the creepy taxidermized albino deer on the wall, was the site of the original picnic pavilion. I showed my prowess for archery on the old picnic grounds. I shot .22 rifles next to the site of the two-story restaurant, and shotguns near the bandstand. I learned about bear traps next to the rollercoaster. I played on those rusted swings, left over from a century before. And the weird stone memorial that was fenced off and overgrown? It was the foundation of the 120-foot Electric Tower.

It’s no surprise that from a young age I was familiar with the experience of being in a place and sensing its long-forgotten history all around me: the Oil Region (and the Rust Belt as a whole) are rife with places that no longer bear resemblance to what they used to be. It is a fact often lamented.

But even before I knew this place as Monarch Park, something about the scattered foundations, the random metal tracks half-buried in the earth, and the elegant stone bridges over the creek, clued me in to something greater going on. It was as if the memory of the place, the memories of all the people who had spent their many hours there just as I was, were quietly whispering to me, begging me to take another look.

I get sentimental about places, especially forgotten ones like Monarch Park. They’re a bit of a bummer, a bit sobering, a bit sad. But I think it’s a good kind of sadness. It’s the kind of sadness that reminds us that life is short: our joy and sorrow are fleeting, the places and people we love are temporary and the extent to which the world will remember us is limited. We don’t like to think about this as human beings. We like to think we’re the main characters of the world’s story, the center of it all, like a 120-foot Electric Tower of light rising high above a magnificent amusement park.

In reality, we are not permanent fixtures in the world. Instead, we are… people. Spending a little time here before moving on, experiencing great joy and pain and doing our best to create beautiful moments wherever we can. Like the many forgotten people in these pictures, our story is short, but the joy and beauty left in our wake are not insignificant. When I look at the faces in these pictures, I see a moment of life, which is in itself a thing of value.

I see a place that was beloved, and I am inspired to bestow all forgotten places with that honor again.

Hannah Allman Kennedy grew up among the oil ghost towns of Venango County, PA. She is the author of And It All Came Tumbling Down, which was awarded Book of the Year at the 2023 Writer’s Conference of Northern Appalachia. She lives and teaches writing in Pittsburgh, and can be found online at hannahakwrites.com