McKeesport, Pennsylvania has been through two Great Depressions. Its recovery from the first holds lessons for today.

By Taylor C. Noakes

Visitors to the McKeesport Regional History and Heritage Center are encouraged upon arrival to enter a corridor and enjoy a ‘walk through time.’ The corridor, lined with outlandish fashions and records taped to the walls, features exhibits on McKeesport’s former department stores, its now shuttered daily newspaper, and a former landmark hotel. Perhaps atypically for a former steel town, the images featured focus not on smokestacks or furnaces, but on McKeesport’s former central business district, and the pleasant Boomer memories of post-Second World War prosperity.

McKeesport today bears little resemblance to the city commemorated in its history museum. It’s no longer the nation’s leading producer of steel pipes, nor the commercial and industrial center of the Mon Valley Region, but rather a small suburban community on Pittsburgh’s periphery. The city’s poverty rate is more than double the state and Pittsburgh metro levels, at more than thirty-one percent, with forty-nine percent of children under the age of eighteen living in poverty. Its median home value, $48,000, is a quarter of the state’s and a third of the rest of the Pittsburgh metro. Twenty percent of housing units are vacant, and half the population moved between 2000 and 2014. In 2019, a national trade association for the home security industry ranked McKeesport America’s fourth-most dangerous city.

The story of what happened to McKeesport, like so many places in the Rust Belt, is a story of the relationships between labor and industry, of the collective power of communities to shape their circumstances, and of the forces that conspire to keep this power at bay. Its history is shaped by two ‘Great Depressions’—first, the one everybody knows about, in the 1930s, and again in the 1970s and 80s, when the oil crisis led to a downturn in steel production and a tremendous loss of jobs and industry (cumulative job losses since the mid-1970s are estimated at 175,000).

The Mon Valley and the community of McKeesport never recovered from that second crisis. This contrasts sharply with the first, when organized labor succeeded, albeit briefly, in securing for steel industry workers the wages, benefits, and job security that had so long been denied them by U.S. Steel and its local political allies. That hard-won prosperity and security would ultimately last only two decades before a combination of factors conspired to undermine and overwhelm what was once the beating heart of the American steel industry—but it carries important lessons for those who hope to rebuild thriving communities in the Rust Belt.

Well into the third decade of the twentieth century, working conditions in the large industrial concerns that defined the McKeesport community bordered on intolerable. Most workers toiled for excessively long hours in dangerous conditions for pitiful wages. Discipline in the mills could be enforced with beatings or firing without cause. Complaints could result in losing one’s job, as could sickness or even an injury incurred while at work; in 1910, in more than half of the workplace accidents resulting in injury or death in Pittsburgh, the employer bore absolutely no responsibility whatsoever. There was no recourse outside of organizing, and even that brought with it serious challenges. In Pittsburgh specifically, union organizers were harassed and beaten by Pinkerton detectives working for the major steel companies, and meeting halls were closed by the Board of Health for unsanitary conditions. (Duquesne mayor James Crawford famously boasted that Jesus Christ himself couldn’t hold a union meeting in his town.)

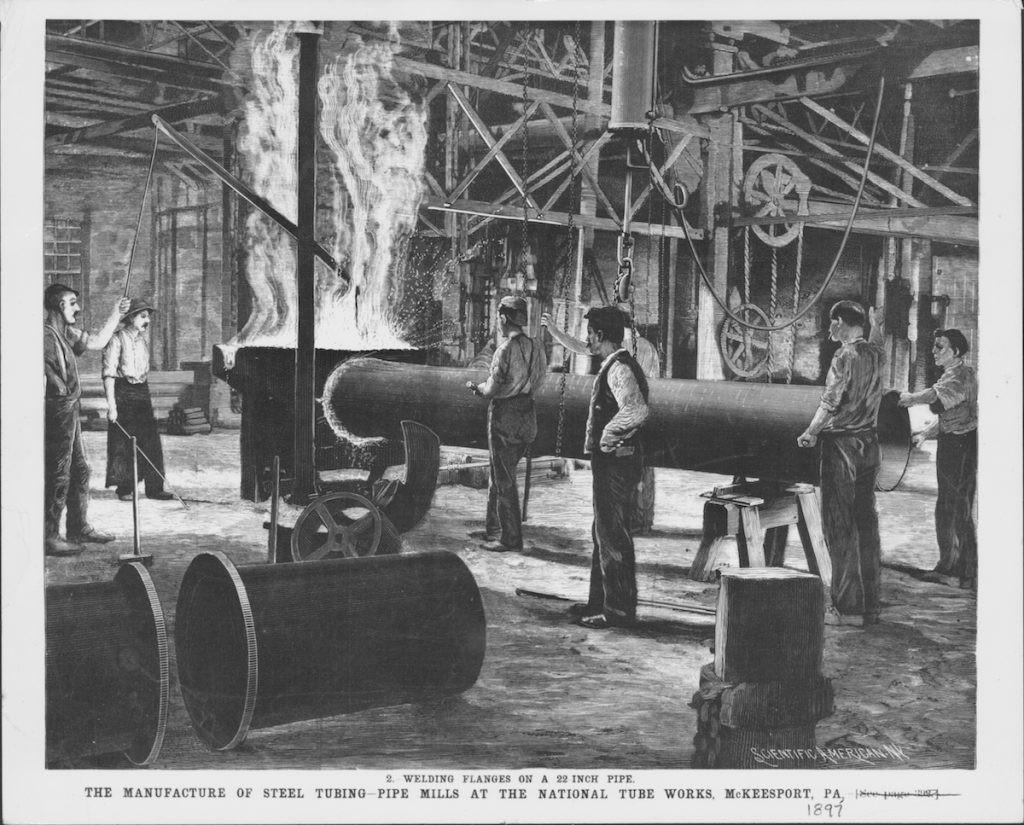

Engraving of the manufacture of steel tubing pipe mills at the National Tube Works, as printed in Scientific America, McKeesport, PA, 1897. American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images.

Though the American steel worker had secured a modicum of job security and a reprieve from this brutal exploitation during the First World War, at the war’s conclusion the steel industry sought its own ‘return to normalcy’ and an elimination of all the benefits that had been gained to keep the industry running. The Great Steel Strike of 1919 demonstrated that there was considerable labor unrest in the immediate aftermath of the First World War.

McKeesport was at the center of considerable labor organizing during the 1920s and 1930s. This was the era of the Red Scare, and anti-union sentiment was widespread. Phil McGuigan, a McKeesport worker, recalled that private detectives spied on employees to prevent unionizing. McGuigan also remembered an informal system of patronage was the primary means for gaining employment, and that Mayor George Lysle forbade the renting of halls for union meeting purposes. In 1923, several members of the Workers’ Party were fined for holding an outdoor meeting on private property after being denied the right to rent a hall for the same purpose. After the meeting, McKeesport’s major employers went about dismissing “…all employees who were known to have attended the meeting or to have been identified in any way with it or the Workers’ Party.”

McKeesport resident Junious Brown, interviewed in 1983 by the McKeesport Oral History Project, recalled that the steel mills of the Mon Valley largely fell silent during the Great Depression, noting that McKeesport’s primary employer, National Tube, ceased operation during the Great Depression, as did the nearby Duquesne Works. Nearly all the locals interviewed for the said that jobs, food, and money were all in short supply, but that most people didn’t leave their homes or the community unless they were forced out. Those interviewed, Brown included, spoke in glowing terms about the union movement, which helped the citizens of the Mon Valley weather the storm of widespread economic collapse.

Labor organizers, including communists, were known for taking direct action to help people in trouble. Rocky Doratio, who was active with the Unemployment Council (UC) movement prevalent in the Mon Valley at the time, said when peoples’ utilities were shut off, UC members would “go around turning the gas on; water and electric too,” and that UC’s membership would show up in force in case one of their members were threatened with eviction. Similar tactics were employed to ensure the prompt distribution of welfare checks. (Joseph Odorcich, who became vice president of the Steelworkers’ Union in the 1980s, told interviewers: “I said in the ‘30s we were that close to going communist. One of the reasons was, in those days they were the only ones who would help you. If the company shut off the gas, the commies come in at night and turned it back on.”)

Several of the interviewees related how social solidarity during the Great Depression knocked down interracial and inter-ethnic barriers that had been previously exploited by major employers and the political class alike. Junious Brown recalled that the unions improved his job prospects, such that he and other Black people were no longer limited to “…the hardest, dirtiest jobs.” Andrew Jakomas, who served three terms as mayor of McKeesport from 1953 to 1965, recalled McKeesport during the Depression was a multi-ethnic melting pot, but that politically the city was a “closed corporation” where “ethnics and Blacks” had no chance of holding political office. Jakomas summarized the general support of citizens for the various federal government ‘make-work’ initiatives of the New Deal, stating that “…we all became Democrats with Roosevelt.”

As McKeesport native and veteran labor reporter John P. Hoerr relates, the ‘good old days’ of working in the steel mills was in the post-World War II period, when organized labor had secured a good deal for the working man. The postwar period witnessed considerable labor action on the part of the United Steelworkers (USW), which contrasts sharply with the stereotypical image of postwar domestic tranquility and social conservatism. In fact, in the fifteen years that followed the Second World War the USW went on strike five times (in 1946, 1949, 1952, 1956 and 1959), the last of which involved more than half a million workers and lasted 116 days.

Support independent, context-driven regional writing.

The steel industry employed about eighty thousand people in the late 1940s, with most of the jobs concentrated in the Mon Valley. While the majority of principle employers were involved in steel (and U.S. Steel was without question the dominant employer in and around McKeesport), the city had a sufficiently diversified economy that it had emerged into a regional center and not merely a mill town. Despite this economic diversity, and despite increased labor activism that led to the formation of the United Steelworkers, U.S. Steel remained both locally and nationally dominant, such that major changes to the industry were bound to have a serious and negative ‘trickle down’ effect on mill-dependent communities and the various industries involved in steel.

In 1947, the Taft-Hartley Act, one of the most sweeping pieces of anti-union legislation in U.S. history, was passed over the veto of Harry Truman. Among the act’s various provisions was the right for states to pass ‘right to work’ legislation, which outlawed “closed shop” union organizing and allowed non-union workers to hire in—a major blow for union power, and perhaps the singular aspect that secured bipartisan support from the ‘Dixiecrats’ and curtailed union organizing in the South.

By the middle of the century, as the economic foundation of the Mon Valley was being hollowed out, so too was its urban environment. Whole sections of the city, including much of its antique affordable housing stock, was razed to make way for large-scale urban renewal projects that never materialized, and the land was ultimately handed over to the steel firms. Population displacement was motivated first by a desire to ‘clean up the slums’ and ‘reduce crime,’ but ultimately served to provide inexpensive land to massive corporations. While communities across the country wiped the slate clean of urban neighborhoods, they were simultaneously losing residents and their tax bases to new suburbs.

The racial characteristics of McKeesport were also changing, with the Black population representing about twenty-one percent of the total by 1971 (it’s about thirty-six percent today). After the city desegregated public housing in April of 1971, white people began distributing thousands of crude racist pamphlets. Anti-Black racism in McKeesport and the Mon Valley Region was not limited to the distribution of pamphlets or lethargy in the integration of public housing, however; Black people generally had few options for employment and fewer still for advancement, and were first to be laid off from the mills.

By the time of the second oil crisis, in 1979, a global recession was brewing and analysts started warning of the possibility of an oil glut. By 1981, the American economy was in full recession, and demand for American steel, like McKeesport’s tubes and pipes, was plummeting. The company laid off more than six thousand workers in the Mon Valley by November of that year. The following month, it used $6.3 billion in federal aid to purchase Marathon Oil as part of an economic diversification strategy meant to satisfy the interests of shareholders; steelworkers complained the funds should have been used to upgrade mills to make steel products more internationally competitive.

More than five hundred companies declared bankruptcy in America during one week in June 1982, with more than fifty thousand businesses failing across the county in that fiscal year. Unemployment in the Pittsburgh Metropolitan Area reached nearly sixteen percent in 1983, with 168,000 people seeking work. Though the rate declined to under eight percent by the end of 1986, in mill towns the numbers often exceeded twenty percent in terms of real unemployment. Research from the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work revealed that between 1981 and 1986, in one out of three Mon Valley households, at least one member had been jobless for a year or more.

McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Photo via Flickr (creative commons).

In October of 1986, twenty-two thousand USW members walked off the job as negotiations broke down; the strike would last six months. When the strike ended in February of 1987, the 189 remaining employees who reported back to work at McKeesport’s National Tube Works were told their plant, in operation continuously since the 1870s, would not re-open. Twenty-one employees were retained to conclude the last shipments and assist in stripping the plant of its remaining useful technology and equipment. (U.S. Steel would transfer its tube and pipe operations to Fairfield, Alabama, where union organizing was more difficult.)

By 1986, population loss had left five hundred abandoned homes throughout McKeesport and over half a million dollars lost in tax income. Young people had been moving out in droves for some time; seventy-four percent of the 1986 graduating class of Duquesne High reported they would leave the Mon Valley for better opportunities elsewhere. Public services, from police and firefighters to street cleaners and public works employees, were cut in communities large and small throughout the region. Though McKeesport would experience a brief resurgence of activism in an effort to save the community in the mid-late 1980s, their efforts were largely unsuccessful. With the loss of the economic foundation of the region, those who could afford to move elsewhere did so, and the population of McKeesport continued to shrink and grow older.

It’s hard to be hopeful walking past the endless rows of abandoned storefronts and the crumbling buildings of McKeesport’s once bustling downtown, and yet, a century ago, at a time in which nearly all hope had been lost, the people of this city secured for themselves a new and better deal. Though McKeesport transitioned from a bustling regional commercial and industrial center to a declining residential suburb over the course of the last century, there may yet be a stable foundation for renewal.

The community that remains occupies land once reserved for the local elites, stretched along Eden Park Boulevard and focused on the few remaining community institutions, such as the local high school, Renziehausen Park, and the churches that proudly boast of their ethnic heritage—Polish, Ukrainian, Hungarian. Down the hill, toward what was once McKeesport’s central business district, is an abundance of open lots and derelict buildings. Racial divisions seem to remain, with the upper part of the community noticeably whiter and better off than the segment that lives down the hill; McKeesport’s Black population has increased substantially over the past decade, like the other communities of the Mon Valley, as Black people are displaced from Pittsburgh’s gentrifying urban neighborhoods.

In the Mon Valley, the organization of municipalities still reflects the preferences of U.S. Steel from more than a century ago. Communities remain disconnected from one another, despite geographic proximity and near socio-economic uniformity; McKeesport is only about twelve miles from downtown Pittsburgh, but the drive can take as long as forty-five minutes. This planning was often deliberate, as major industrial concerns like U.S. Steel simply didn’t want their employees mixing with the employees of other mills for fear they may unionize.

Politicians often say there are no simple solutions for what to do with America’s devastated industrial cities, but the beleaguered citizens of these communities are under no illusion that easy solutions exist. Despite baked-in divisions, the workers of the 1930s found common cause, and learned, as did working people across the country, that the power of the industrial bosses was largely an illusion. It was easy to stop evictions when masses of people showed up to stare down the sheriff, and relatively simple to turn the utilities back on with the help of the neighborhood electrician or plumber. The likelihood of police violence and suppression fell with every new person attending an outdoor rally right in the middle of town. Churches and schools, street corners and shops became the venues for impromptu meetings, discreet sharing of information, and the ever-increasing organizing web.

Residents of today can take a powerful lesson from McKeesport’s first Great Depression. The strength of the town in the twentieth century was built on an infrastructure of connection and organizing across differences—geographic and otherwise—and offers a compelling blueprint for rebuilding strong Rust Belt communities in the future. The steel mills may not be coming back to the valley, but that’s no matter–they weren’t really what brought these communities together in the first place. ■

Taylor C. Noakes is an independent journalist and public historian currently based in Pittsburgh. He is a graduate of Duquesne University’s MA Public History program and is currently working on preservation and rehabilitation projects for a Pittsburgh-based architectural firm.

Cover photo of a steel plant in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, 1957. Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images.

Belt Magazine is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. To support more independent writing and journalism made by and for the Rust Belt and greater Midwest, make a donation to Belt Magazine, or become a member starting at just $5 a month.